A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 12: Art School

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 12: Art School

Author: Alistair Knox

I was transferred from Port Melbourne to the Swanston Street office in 1930, which was an agreeable change. There was a staff of twenty-four under a white-haired bachelor manager who was nearing the conclusion of his service with the institution. His surname was Nason but he was universally 'Nase' to all who knew him. The accountant, Mr Astley, was a correct, English-looking gentleman with a slightly aristocratic attitude; he had married late in life. We noticed that he was always irritable on Wednesday mornings - perhaps, we calculated, because he might be having sex regularly on Tuesday nights: the excitement was becoming too much at his advanced age. Our staff, entirely male, seemed to be much more contemporary than that of most other offices, and our days were filled with practical jokes and with sneaking out early to go to the last two races in hopes of winning a quick fortune. The whole office was similar to a boys' school where everything had to be done by stealth. Mr Astley's office was situated in the centre of the proceedings. It contained a hat rack for his bowler hat and neatly folded umbrella. Joe Speakman, the office funny man, would occasionally appear over Wal Astley's shoulder as Wal tried to communicate some meaningless piece of information to a co-worker, holding him with his glittering eye like an ancient mariner. The listener would be aware of Joe's presence, while his own gaze had to remain fixed on Wal in an effort to maintain a straight face. Although Joe might be only two feet behind Wal he would produce a grotesque face, lift Wal's bowler hat off its peg, don it for a second or two, replace it, and then vanish with miraculous speed just as Wal became aware something was wrong and turned around too late to catch him. My duties were mainly concerned with checking passbooks - the final degradation to which it was possible to sink. This operation went on without interruption throughout the working day. Passbooks containing withdrawals arrived into the centre of the office from one corner called the 'verification counter' after the depositor's signature had been passed. Each passbook was extracted with a hiss and a bang from the compressed-air carrier tube. We then took it to the ledgers to compare the balance with the bank ledger. From there the passbook was placed on a counter to be recorded when passed through to the teller for payment. The office was busy, and checking passbooks kept Brendan Kelly (the junior) and me (the second-lowest staff member) moving quickly all day. I never calculated how far I walked during those book-checking years, but the task left me weak in the legs and head. The daily release from work was like breaking up for school holidays.

The Nicholas Building. Photo: http://www.worldofbuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/9-hidden-gems-in-melbourne-that-will-make-you-want-to-visit-melbourne-again-world-of-buzz-19-1024x683.jpg

The Nicholas Building. Photo: http://www.worldofbuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/9-hidden-gems-in-melbourne-that-will-make-you-want-to-visit-melbourne-again-world-of-buzz-19-1024x683.jpg

The Swanston Street office was on the corner of Flinders Lane opposite St Paul's Cathedral and adjacent to Nicholas House, which was a 1930-height-limit building. We could see many of the city's activities through our windows, and we were only a stone's throw from the Flinders Street Station. In those times of poverty, many odd methods of creating a market for one's talents were tried; few were more original than that of an escapologist who volunteered to escape from a strait jacket while suspended upside-down over the main city street. The police, however, banned his proposal because they correctly assumed it might bring the city's busy Friday lunchtime traffic to a standstill This was the perfect opportunity for 'Ossie' - one of our more cavalier characters - and one of his cronies to set up an effigy of the aforementioned escapologist, dangle it on a pole from the roof of our building, and then duly send it out into the void. Within a minute the crowd had gathered, using the entryway to St Paul's opposite as a God-given vantage-point. Five minutes later, the traffic had came to a halt and Ossie and his assistant decided to stop, that is, until Monty, a young, fresh-faced, bespectacled junior, arrived to join in the fun. Ossie and his friend asked Monty to take over and keep wiggling the strait-jacketed ghost until their return in a few minutes. Monty was delighted with this sudden sense of power; as he meditated on whether to cut it down or bring it in, the police arrived. This prank was one of the best free diversions the sombre times had given us for months. Despite the fact that our salaries had been temporarily reduced by ten percent we were, still, relatively free and well off.

I finally persuaded my mother to desist from making me attend the classes necessary to obtain an accountancy qualification - these would only enhance my non-existent advancement in the bank. Instead, I decided to attend the Art Gallery night classes at the Public Library Building. Occasionally Bernard Hall , the vitriolic director, was the instructor. I assiduously avoided him and meanwhile sought out the soft, non-definitive views of Charlie Wheeler, the other instructor. I was aware that the visual arts were not my field, but they were great fun. The whole Australian art scene was still in the viselike grip of the Realist painters despite the Modern Art movement of Europe. Cezanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and their contemporaries may have been appreciated in Europe; but we Australians were still dubious about all those frenetic sunflowers, the ancient half-articulated landscapes, and the nude fruit-carrying Tahitian females. Gertrude Stein might write 'A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose', but we found that the rose had always wilted in the morning. We were entangled in the web of dividing between what we saw and what we believed - a very strange contrast.

I discovered my first prophet of the Modern Art scene one evening as I toiled away at a plaster cast of Richelieu, whose subtle shades and suave expression were far too much for me. The Michlet paper drawing paper became greasy as I tried to re-create the subtle mysteries of that impenetrable face. Suddenly Sam Atyeo burst on the scene of my charcoal obscurity with a mid-day brilliance. He quickly became the author of my inspiration. He was a product of Coburg, a northern Melbourne suburb in the midst of the volcanic bluestone deposits that form the basis of the city. His father was a foreman in one of the local quarries. From that humble background Sam had graduated, through some architectural training, to the Gallery, where his ability and his advanced thinking were having an effect.

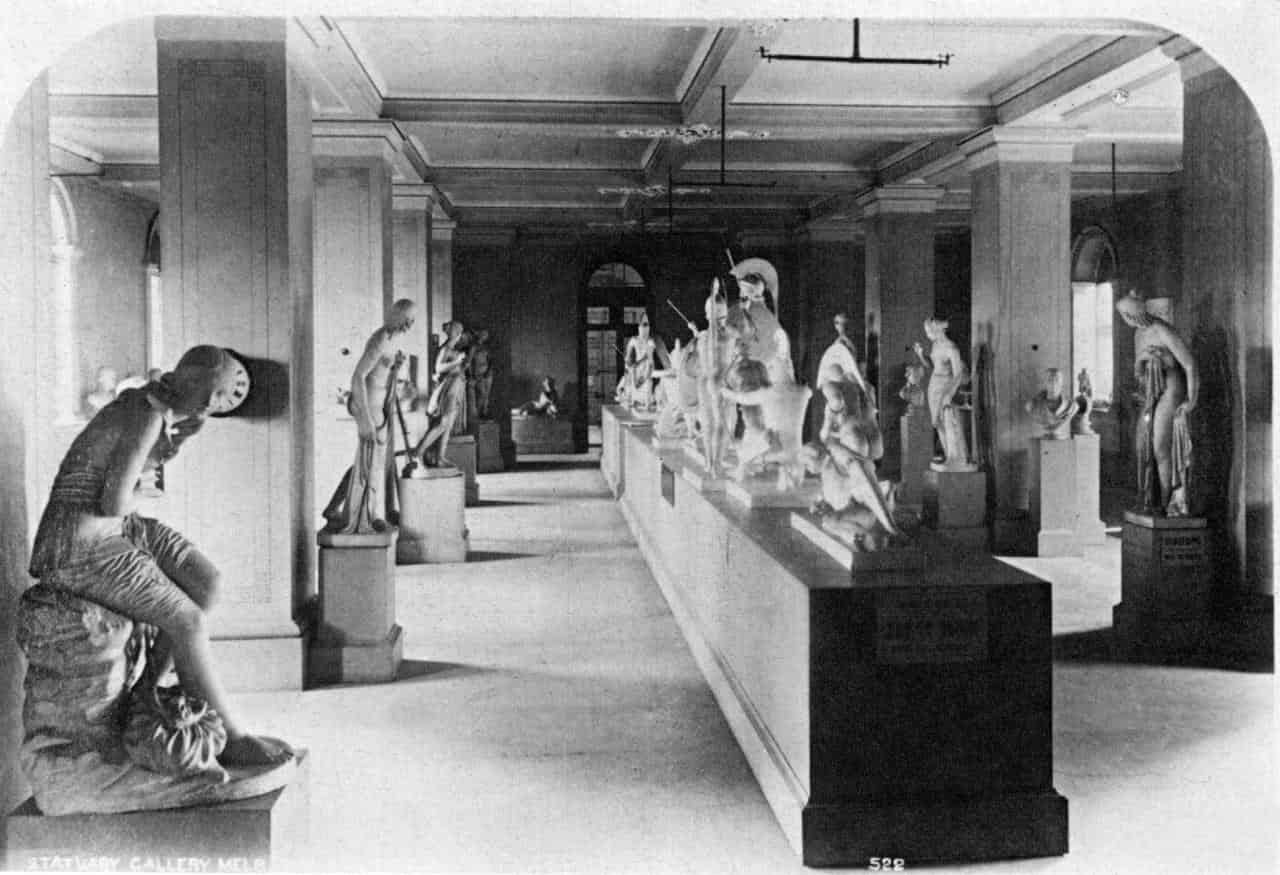

Plaster casts at the Nationa;lGallery of Victoria

Plaster casts at the Nationa;lGallery of Victoria

For 7/6d. a week there still were good studios available for the 'modern' painter off Little Collins Street in Gunn Alley, and in Pink Alley, the scene of a famous murder some years earlier. But the great studio in all Melbourne belonged to John Vickery, a commercial artist of great skill who occupied a loft and stable above a horseyard that still gave entrance onto Collins Street via the Holly Tea Rooms at No. 92. This was a time when Melbourne still was Melbourne, and one felt it actually possible to see streaks of gold scintillating in the sun after a sudden burst of rain.

Sam Atyeo was a well-framed man when I first met him. He had lank auburn hair, a freckled face, and a highly disreputable vocabulary. His voice was cohesive but angry, his arguments verbose but convincing. He set up his easel next to mine, and started to draw the Michelangelo slaves all neatly encased in their immaculate white plaster. As Sam worked, I immediately saw a difference between his attitude and mine. Where I tried to keep everything in a state of photographic vagueness, he would invest his conception with a careless reality that placed first things first and the agenda nowhere. He always worked with great speed and great freedom. His colourful language added a certain volatility to that erstwhile academic institution and generated an entirely new dimension. He immediately became the watershed of the past and the future. I was able to keep abreast of this new and dynamic influence; it would soon divide Australia into two diametrically opposed artistic camps. And despite the fact that to me Sam was at the opposite end of the spiritual spectrum, he was stimulating and persuasive. I stood at a watershed of decision. Behind lay the conservative and the substantial; before lay the future and the indefinable. For the first time, I had to come to grips with those French Impressionists and their contemporaries like Picasso and Bonnet and decide what they were on about.

I soon witnessed what a skillful craftsman Sam was as he tackled his plaster-cast drawings of groups of Greek mythological heroes. He was uncompromising in his approach, and he reached the heart of the subject with great rapidity. He strode up to and back from his easel like an athlete; with broken sticks of charcoal strewn about the floor, he would talk incessantly as he critically examined his progress. This was a completely new approach to me, and it strode over my nebulous thinking with seven-league boots.

Sybil Craig 1930. State Library of Victoria

Sybil Craig 1930. State Library of VictoriaSam was always at loggerheads with the director, Barney Hall, a skillful realist technician as well as an autocrat who always demanded high deference to his opinions - entirely the opposite of what he received from his talented pupil Sam, who had the effrontery to say that not all modern art was necessarily bad. Barney received great hero-worship from most of the young female students, who were still a great way from the emancipation of their sex and felt that their only hope of success lay in suitable subservience to the master. The women full-time students, whereas I only attended at night. The fees were only a few shillings a term, and the social factors alone made it well worthwhile, especially in those Depression years. Two artists' balls were held each year, and they were always the high point of the season. We used to get free tickets in exchange for decorating the Victorian Artists' Building in Albert Street. Sam was in his element on these occasions. We would stick together large squares of brown paper to form enormous canvasses. Sam would draw great figures of fun and ridicule on them, and we would then colour them in and hang them. In a time when the advocates of opposing artistic philosophies argued the merits of their respective views, Sam's natural ability and ruthlessness naturally generated considerable antagonism, and there would always be those who were out to 'get' him or reduce him to their own limited dimensions, partly because he was becoming a danger to them as his new ideas threatened their security. One such person was John Vickery, who occupied Melbourne's No. 1 Studio, which was entered from 92 Collins Street. John, with his magnificent draftsman/commercial-art skills , specialised in producing perfect pictures of the latest motor-vehicle brochures at a time when they were still done by hand. He was very successful, and thought of Sam as a roughneck from the North Coburg quarry area. Attached to John's loft was another tiny sleeping area, which he had recently let for three shillings a week to a poet just arrived from overseas. The poet had brought with him a new publication by Herbert Read which purported to debunk the aspirations of the New Art movement. Sam's antagonists decided to upstage him at one of the Decorating Sessions, and to expose him for the upstart they believed him to be. But Sam was no sluggard about gathering and evaluating opinions about painting. He had obtained a copy of this new publication a day or two before from John Reed, who would become the centre of the contemporary-art scene for many years. When the stage was finally set and Hannah and John Vickery attacked Sam, they were more than surprised to discover that he had read the book from cover to cover - considerably more than they had done. Sam quickly took the initiative, and within half an hour he had stripped the opposition naked; they flew from the field along with their supporters, who formed about seventy percent of the audience. The remaining amongst us smugly gloated for awhile, but we knew things would never be quite the same again. I was a frequent visitor to John Vickery's loft, particularly after Hannah's arrival; as I wrote a considerable amount of verse, and because as John was a poet of some standing, his opinions were profitable to me. One day in the courtyard at John's, I met a man on crutches; he looked deeply into my eyes as we were introduced. He was Alan Marshall, who became one of our most celebrated writers. I eventually formed a close association with him, and he was always one of the most generous and charming men it was possible to know. Because Melbourne has always had the quality of an oversized village, those who entered any philosophical, educational, or artistic part of it would before long get to know everyone else in each other part. This phenomenon continues today - with both its advantages and disadvantages.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >