A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 38: Eltham Films

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 38: Eltham Films

Author: Alistair Knox

When Margot's confinement was imminent, she went to stay with the Hattams in Canterbury. Hal Hattam was a skillful gynaecologist who also became a fine artist. He and his wife Kate and their children lived close to John Perceval, whose wife Mary was also Arthur Boyd's sister. It was the period when the painters were rapidly becoming independent. They had had all their babies delivered by Hal and had always paid for them with paintings, which meant he finished up with one of the best antipodean painting collections in existence. Not to be outdone, Margot arranged to do slate-paving in the Hattams' garden, in exchange for her confinement. The whole social climate was suffused with a great spirit of doing and being. The residents had not yet become unduly rich and divided, and it was still difficult to decide who was becoming affluent and who was not. Our first son, Hamish, was born in April, and we went to live in the farm cottage, where he quickly became the special object of Mrs Fabbro's concern and penetrating voice. I was working by the wood-fire stove one evening after dinner when a knock at the door announced the presence of two policemen. They had come to inform me that Mernda had been killed instantly by a hit-run motorist. As I recovered from my initial numbness and shock at the sorrow and the shortness of her life and its lack of fulfillment, I realised that a new era was opening up for me. After a suitable pause, I would, naturally, go on to marry Margot, and we would go to live with my other three children in my old house on the other side of the valley. When the wedding took place some three months later, a general sense of order and well-being had been restored. John and Mary Perceval were our witnesses at the Registry Office, and we returned to their house for a quiet reception which included Dick and Dorian, Gordon Ford, and our intimate old friends.

Our financial difficulties continued despite the original quality of our design concepts and work. The proliferating age generated its own alternatives, which were further stimulated by the fact that Melbourne was to be the host city for the Olympic Games of 1956. With true Australian pessimism, our general opinion was that we would make a great hash of the whole affair. Some were quick to point out that the Olympic Village at West Heidelberg was minimum-standard building for low-income families, and that the sporting facilities and the food for the different nations, along with hundreds of other considerations, would be parochial and sub-international. As the opening day drew close, television made its initial appearance - which was considered some advantage - but the weather was atrocious, with sheets of rain every day until two days before the games were due to start. Then, miraculously, the downpours ceased, and it did not rain again until the events concluded two weeks later.

The Australian team march around the MCG during the Opening Ceremony of the 1956 Olympic Games

The Australian team march around the MCG during the Opening Ceremony of the 1956 Olympic Games

Every aspect, from the opening to the closing ceremonies, went off perfectly. The organisation was impeccable, the food inconceivable. Any dish from anywhere in the world was available immediately and, by way of a bonus, Australia came in third behind the United States and the Soviet Union in the medals count. The thrill of walking from Spring Street to the Melbourne Cricket Ground and into the stadium among more than fifty nationalities - many in their national costumes - produced emotional lumps in our throats. It was our greatest moment. Melbourne became the most urbane city in the world. There was an equality and freedom without fear that has seldom been equalled anywhere before or since.

The great difference that separated Eltham from any other locality in the entire continent was the sense that we were not divided into rich and poor, wise and simple, but were one united community with common hopes and aims. It was well understood that the natural bushland beauty, which had defied development, was fundamental to our survival. When a children's competition coined the phrase Keep Australia Evergreen, it provided us with a rallying point that did not change for twenty years.

The shouting and cheering of the Olympic Games had barely subsided when the community gave special evidence of this very quality. Our arch-enemy - the State Electricity Commission - had received more than it had given to the Eltham residents; and when it sought to desecrate the tree-lined country roads, it became very wary and had to proceed by stealth. Thus, the distant drone of a chainsaw would immediately set the entire community on edge, sending residents into the area from which the noise originated to find out what was happening.

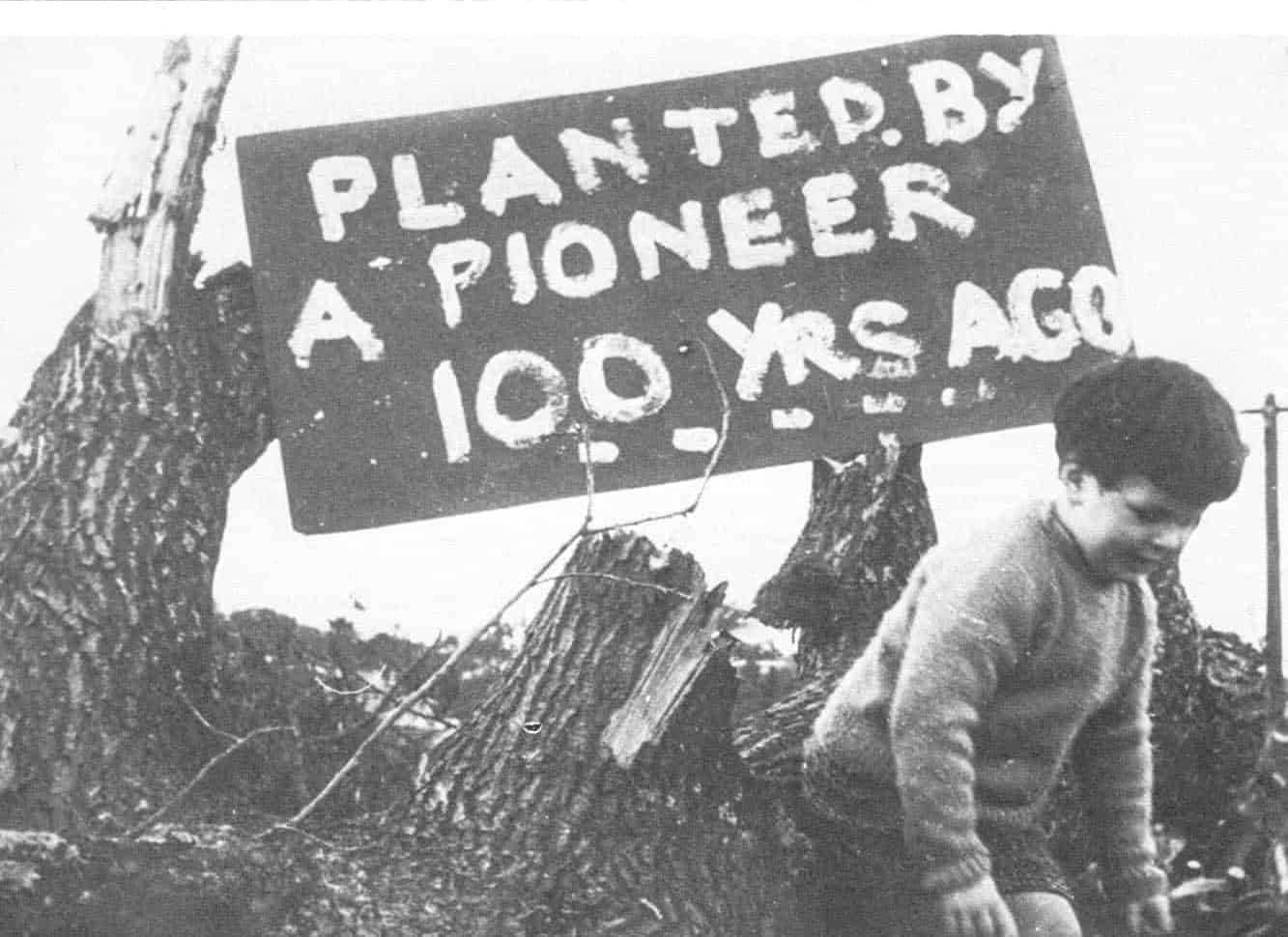

My son, Hamish (aged 2½ years) attending his first protest against the depredations of the Sate Electricity Commission 1956

My son, Hamish (aged 2½ years) attending his first protest against the depredations of the Sate Electricity Commission 1956

One warm evening just before Christmas, we were sitting around in relaxed conviviality, our ears dulled to the sounds of enemy action occurring outside. The noise was so prolonged and consistent that we did not think it could possibly be a chainsaw at work. It sounded more like some major work being done far down the main road - this would be beyond our control. It was getting towards dark when the hideous truth revealed itself. A team of Commission workers had felled two great oak trees in Franklin Street - a quiet cul-de-sac beside the main road near the pub - and cut them up. They were one hundred years old and a fundamental element in the townscape. Their disappearance was as conspicuous as the loss of two large teeth. The onslaught was so brazen that we did not know whether to blame ourselves for grossly underestimating our adversaries, or to admit we had been beaten by their audacious skills. One thing was certain. We had to fight back! All the daily papers were alerted and we made arrangements made for press photographers to record the carnage in the street - along with the blazing eyeballs of the inhabitants. Large signs were erected on the site; the main result, though, was a sense of frustration and helplessness. In the 1950s, however, there never seemed to be any worthwhile news around on Christmas Day, and the dailies took up the story. We skillfully kept the flames burning for the next six days across the entire country. After four days, coverage was appearing in the New York Times; Eltham trees had become worldwide news. Defeat was turned into victory, and the Commission didn't fully recover for another twenty years. Their tree-lopping had to go on, but they always looked the other way if they happened to see us while they were working somewhere. In fact, their chief executive issued advisories warning his employees of the importance of trees.

The next year, there occurred periodic insect infestations, which caused high casualties in the local eucalypt forests. Our Tree Preservation Society indulged in a well-organised aerial spraying program that drenched the district with DDT at considerable expense and ourselves with a cloud of self-righteousness. We subsequently came to the conclusion that it was truly providential that we had not exterminated a large proportion of the local birdlife and possibly some of the local residents as well. But right or wrong, we were united - and capable of defending ourselves against all comers. The cause of one became the cause of all. I gradually became less involved in the purely social activities, and more immersed in the Christian experience. Alcohol was a strong component in our community intercourse, and I had been drifting into excessive drinking which I found myself unable to cure. One day, as I was wondering what I should do next to deepen my spiritual commitment, I clearly heard two words in my mind: 'Stop drinking'. It was the day before our building team knocked off for the Christmas break, when the year's work concluded with a traditional party. I had no difficulty abstaining from alcohol on that agreeable occasion; but the next day, Christmas Day, was a different matter altogether. I sweated it out for one hour at the community Christmas dinner at our house, after which the desire to drink left me completely. I never drank again for at least twelve years. I used to attend our social occasions armed with a bottle of lemonade which still allowed me to feel at home in the alcoholic atmosphere, but was surprised at how quickly some of my companions would momentarily stop hard drinking hard liquor, assist me in depleting my lemonade supply, and then return to their original beverages.

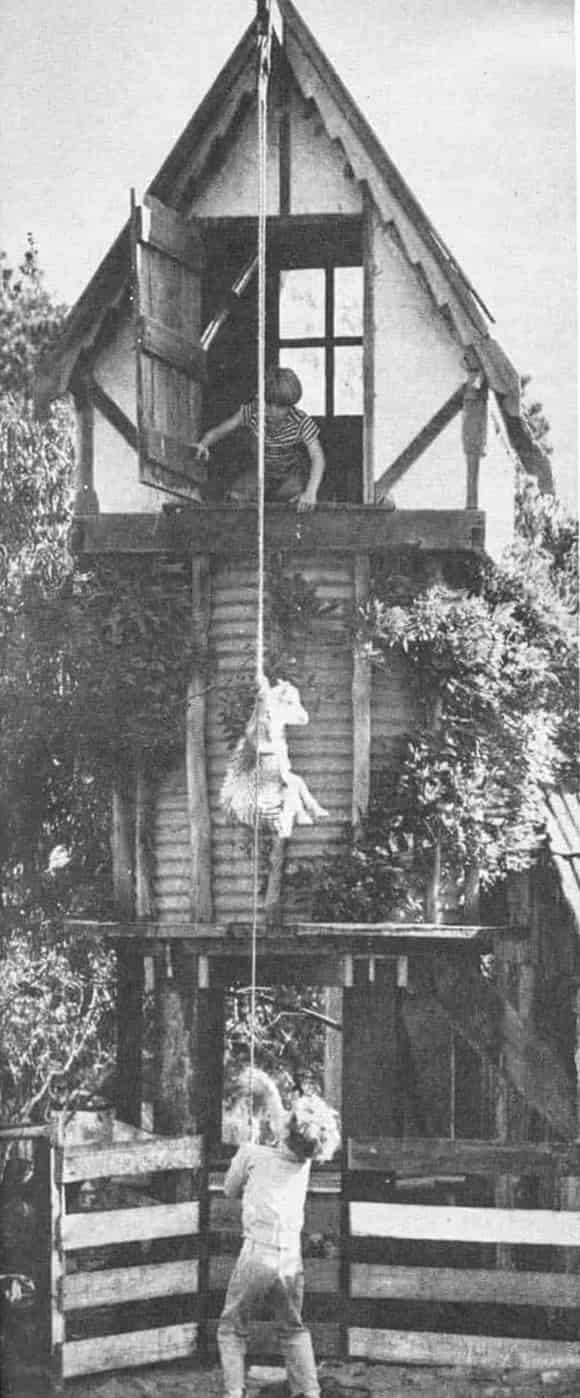

It was on the second day of 1957 that Tim Burstall set out to make his initial major film, The Prize. He was naïve enough to believe that if we all worked together, the project could be completed for a couple thousand pounds. It was an exciting moment when we set up for the initial day's filming on the old wooden bridge that spanned Diamond Creek near the old swimming hole. The adjacent valley landscape was still practically unchanged from the previous century. The locations of the old brewery, the flour mill, and the tannery were close by, but those buildings had disappeared. Only two of the mill-managers' cottages remained, a little further down the road. The scene had a traditional English quality of small square paddocks divided by cherry plum and hawthorn hedges. The occasional iron-roofed cottage with its handmade pink-brick chimney completed the scene, which, together with the creek flowing through it, gave an overall sense of a minor eighteenth-century Constable painting.

Scenes from 'The Prize': Dan Burstall and Marcus Skipper hiding the goat.

Scenes from 'The Prize': Dan Burstall and Marcus Skipper hiding the goat.

The scene being filmed on the bridge consisted of the two Burstall boys Dan and Tom; Matcham and Myra Skipper's son Marcus; and Liza Jacka, a beautiful blonde child three years of age. Dan, Marcus, and Tom were (?__ages__? , in that order. They were filmed fishing when disturbed by Matcham Skipper - alias a local rabbiter - trotting by in his long-shafted jinker, with traps and other impediments dangling from his rustic two-wheeled contraption, over the wooden-planked bridge. On that historic occasion, there was not one modern factor to mar the rural reality. We returned home reasonably satisfied with the progress. Then, after a further two days' shooting, we sent the negative to Lion Films in East Melbourne for processing. A week later, we all went into their studio to view the rushes, which were good except for a fine white line that ran through most of the prints. When it was found that the fault was in the negative and that the all of our work would need to be redone, pandemonium broke out. We blamed Lion Films and they blamed us for some minutes, until it emerged that no argument could eliminate the scratch. It all had to be redone. It was our first lesson in the difficulty of making moving pictures.

The ensuing few months were amongst the great highlights of the thirty years that spanned the Eltham era. The film-shooting changed locations - from the Bolas' vegetable patch beside the creek, to the Morrisons' large acreage on the Yarra River; the front garden at our house; and the nostalgic farm buildings at Montsalvat. All of this was finally capped by a long, hazardous trip down the nearby river in half-barrels over rapids by boys of the cast who could barely swim. The story itself concerned a goal which Tom Burstall, the smallest boy, wins at hoopla at a local show, and which is stolen by the two elder boys of the cast. Liza joins Tom in a search for the missing prize, which ends in its recovery at the river as the sun is descending on the golden autumn of the Australian bush. The whole outside filming was done for practically no cost. My Volkswagen - minus its bonnet and loaded with camera and crew - did all the tracking shots over the paddocks of Matcham and his jinker driving Tom around the back bush roads to the accompaniment of Dorian Le Gallienne's lyrical music. Gerrard, the cameraman - filming the barrels floating down the river from the top of three eucalypt saplings tied together and hanging over into midstream was the extent of our props. Betty, Tim's wife, was the catcher who grabbed Tom, the non-swimmer, as he was tipped out of his barrel at the rapids - recollective of early Hollywood days when the life of extras was cheap, and hazards were the essence of each filming sequence. Tim set off for Sydney to begin cutting and processing the final result. Because we still owed Lion Films some money, we had spent only £500 up to that stage. We were hoping to obtain finance for this part of the project, but it was not forthcoming from any usual source. It only happened ultimately when Patrick and Rosemary Ryan, who were almost our only rich friends, found the £8,000 necessary to complete one of the most economical films ever made. The work was entered in the Cannes Film Festival and awarded a bronze medallion, but distribution could still not be gained for it to be shown commercially in Australia. There had been desultory postwar attempts at restoring a local film industry, but it did not materialise until Tim and Eltham Films continued to persevere after The Prize had achieved some recognition. It was followed by 2000 Weeks and Stork, but it was ALVIN PURPLE that set it on a financial career.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >