A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 40: Hard times

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 40: Hard times

Author: Alistair Knox

The year 1961 also saw the first postwar recession in Australia. Fifteen years of euphoria vanished 'like a watch in the night when it is gone'. My building operations were brought to a low ebb, but I remained just solvent through a single contract to build a large house I had designed in Scoresby, an outer area near Ferntree Gully, for a Mrs Benedikt. Many building companies went to the wall at this time as credit dried up and we faced the first breath of winter's discontent for more than ten years. A man named Korman, who was the most flamboyant speculator of the time and who had been busily cutting up the sacred Yarra Valley in the Heidelberg area, was charged with an alleged crime and eventually spent a year in gaol. I had in the meantime had my plans approved and entered into the contract to build Mrs Benedikt's house, which was to be a great gesture to her children and a monument to herself. She had been born in Eastern Europe and had developed a very successful business in women's hats. She had endured hard times in the early stages, which gave her a great sense of survival in success. She was not an easy client, and had probably come to me as a last resort. I found her very 'Jewish' in her accent and approach, but fair in the final analysis. The design was quite good, well-sited, and could prove a good result for all concerned if we all kept our cool. There was another building on her land in which she, her third husband, and an engineer son-in-law had gathered prior to making a site inspection of the new work at around its halfway stage. It was a wet day, and I saw the entourage arriving to give their decision. I desperately needed a 'draw' to enable me to continue. Any delay in this matter would mean a hasty cessation of work. The three entered through the front door, and I overheard them from another room. General sounds of approval came from the inspection of the kitchen, the dining room, and the children's wing. All was going according to plan! When they entered the main living room, however, a series of urgent cries of 'No! No!' split the silence. Mrs Benedikt had reverted to an Eastern European panic. It was a great crisis - the moment of death, or survival. Husband and son-in-law tried to pacify her. 'Rose,' they explained, 'this is how modern buildings are designed', but she just gasped asthmatically in high frustration. Much to my own relief, I felt no panic at all - just cold realism. 'Don't argue', I told the men. 'What is wrong, Mrs Benedikt? What don't you like?' 'It's all that wood and those low ceilings', she gestured, unable to bear the sight that confronted her. I left the group alone for a minute and went into the other room to consider what could be done. One thing was clear: the roof must be raised, and I knew who would pay for it! I looked out over the flats of the Dandenong area, the wintry afternoon sun gradually disappearing in the early-evening mist. It happened to be the shortest day in the year, and I realised any solution would be required in less than thirty minutes, or I would be insolvent. Suddenly, a warm flush enlivened my hopelessness. I returned to Mrs Benedikt and said, 'If the roof were a foot higher, would that suit you?' 'Yes', she sobbed, 'anything to get rid of all those low timber ceilings'. I questioned her son-in-law, who indicated that he was delighted with his wing. The kitchen had a high ceiling, and the dining room, quite baronial, was situated next to the upstairs-bedroom section. Since Mrs Benedikt had already approved those areas I was able to say, 'If I raise the great living room one foot it would solve the matter'. She agreed, so I briefed the carpenters, who were packing up to leave, be there early next morning to lift up the roof with jacks, and continue the work. Mrs Benedikt readily agreed to my offer to telephone her office the next morning; I would report to her that the roof work had been completed, and would then collect my cheque. I don't think the men who worked for me ever realised how much a part Providence had played - at various times in their employment with me - in my ability to pay them their weekly wages. I mistakenly thought this was a crisis to end all crises. There were more to come.

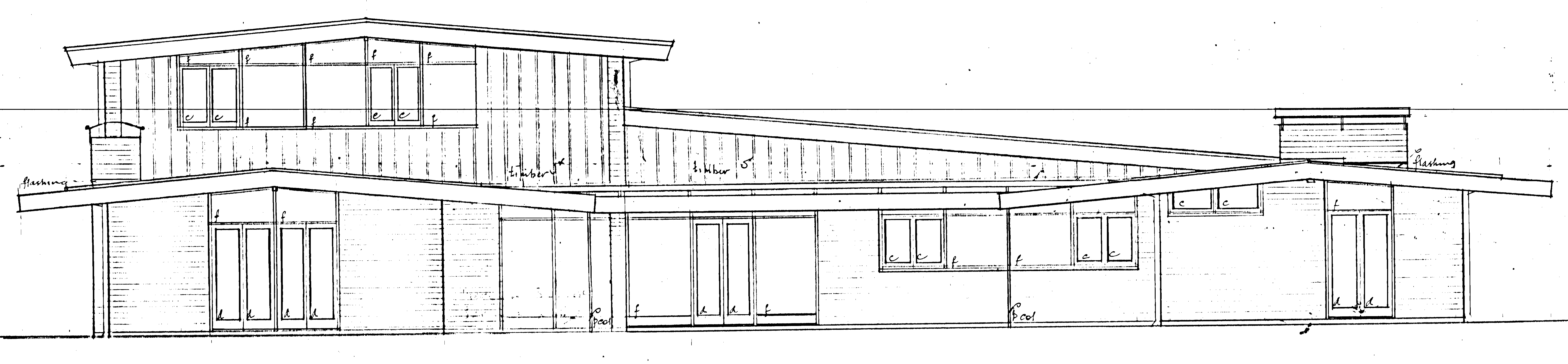

The South East elevation of the Benedikt house, Glenifer Farm, Scoresby, 1961

The South East elevation of the Benedikt house, Glenifer Farm, Scoresby, 1961As the Benedikt house approached completion, my cash-flow position deteriorated significantly. There was little new work to compensate for the plethora of unpaid accounts that kept coming in, some for the second or third time. I could not fathom how I could feel so blessed in my spiritual activities and so neglected in my day-to-day work situation. I was convinced that our youth work was God's will, and equally convinced that I would not be tested beyond my abilities. It all seemed too unreasonable. I felt positive I was doing satisfactory work, yet I was becoming insolvent at the same time. Our clients, even Mrs Benedikt, were satisfied, which was no easy task; yet time after time, some event or circumstance intervened to turn a potential profit into an eventual loss. Margot went to hospital for her third confinement in the midst of this financial dilemma, and our son Alistair was born on 1 December 1962. I found myself living alone in the experimental house I had erected on the bottom of our three acres during the interim to enable us to let the largest building on the property. It was a doubly confusing situation, because I had been miraculously able to borrow money in the recession to finance this project; I took this to be a sign from above that I would come through my temporary difficulties. The building system embodied original concepts that could hardly help but succeed; yet instead, I was getting into a more difficult situation all the time. As I lay in bed early on 4 December thinking over which way to turn next, I suddenly felt as if a great weight were descending on me to crush me into a flat smear. At that moment, I consciously recollected the scene in Chaplin's film Modern Times where he leaves his coat on a great press and sees it flattened out before his eyes. When he finally recovers his pocket watch from the inside pocket, it has grown to a diametre of more than thirty centimetres and become reduced to a thickness of less than one millimetre. I realised there was nothing I could do. I just prayed: 'God, whatever you say, You do it!' I had gone over the edge, and there was nothing else left to do. I accepted the fact that I would become insolvent, but calculated that I should be able to pay my debts by selling our property, which was our main asset. I had formed a limited-liability company, which could have avoided this extremity because the titles were registered in our private names and were not assets of the company. But one thing was certain. Since my conversion, I had become sensitive to things which had not troubled me prior to that time. I suddenly realised that the money I had first invested in building in 1945 had not been honestly earned in terms of my conversion convictions, and God could not bless me in my use of it. This had been the underlying cause of my financial problem. I was determined that any hint of irregularity had to go immediately, despite the fact that I had no notion of how I would survive or whether there would be any money left over. I rose before 8 a.m. and went over to the main office, which was still located in the large front room of the main house, to find my co-worker Peter Glass converging on the same spot. Peter was the most agreeable man I knew. He was both an artist and an easy person to get on with. He hated unpleasant situations and always made every effort to avoid them. Arriving early for work in those days, however, was the last thing he would have contemplated - or that I would have expected of him. The previous year, he had married Cecile, a beautiful French girl whom he'd met in Burgundy ten years earlier. At that time, Peter returned to Australia without having proposed to her, and because he had been seriously ill in the intervening years, he felt his opportunity had passed. Margot noticed his sad expression one day as he was drawing in the glass office of our experimental house. She got the cause of the problem from him, and with feminine foresight and determination persuaded him to send off a letter proposing marriage to Cecile the very same day. Cecile accepted him; this had caused to them to become late starters, but their romance was very gracious and European, with croissants and coffee and the morning paper on the terrace at ten o'clock. For once, Peter was serious and thoughtful, and when I said, 'Peter, I think we are insolvent and should terminate our building activities forthwith', he quietly agreed with me. We went inside and agreed we should draw up a rough trial balance and get this radical decision into action without delay. An hour later, it was becoming apparent that our real problem was not a business failure, but a shortage of money - a situation that would inevitably improve as our work proceeded. At this precise moment the phone rang; I answered it, only to hear the unwelcome voice of the bank manager on the other end of the line. He was a pleasant man, but his was the voice I least wanted to hear; he had been calling fairly consistently over the past few months to see what money would be coming forward to relieve our perennial financial pressures. I got in first: 'Mr Vercoe', I began, 'I am hopeful that our financial position is not as difficult as I thought. In a few months we could be once again trading normally. What I need immediately is some temporary financial assistance to get over this pre-Christmas hiatus'. I then told him, without mentioning names, that I had a friend whom I thought would guarantee me to a reasonable extent in the matter. In the back of my mind I could see Dave Graham graciously coming to my assistance, but my concern was whether the bank would reciprocate in the difficult prevailing financial conditions. The manager, who was normally as affable as he was unbending, took my breath away. 'You've got assets - haven't you, Mr Knox?' he said. 'What's the matter with them?' I had thought they would be unacceptable in those dear, departed times when credit seemed mainly available to those who didn't need it - a practice in the prevailing English banking system designed to keep the working class in their proper station. 'Would you accept them?' I asked incredulously, because money for building was just not available at that time. 'Oh, I think so', came the answer. 'Look, I actually wanted to speak to Peter', he continued. 'Get him to bring the figures down to me. If it's as you say, I think we may be able to do something. You needn't bother to come yourself'. This complete reversal of position without any effort on my part made me realise that God was very much there after all; from that moment forward, I determined to let Him take over completely.

I could suddenly feel the tension that had been building up for months surge through me as I let go. I ached in every fibre. It was as though I had been beaten with sticks all over my body and arms and legs. I was mentally exhausted, but now I felt the crisis was over. 'I must go to the house and rest', I told Peter as he went off to see the bank manager. Back in the house, I just lay on top of the bed trying to understand how it had all happened. As I drifted towards a restful sleep, the bed seemed to be rising and falling, as it used to after I had spent all day in the sea as a child. There was a wonderful sense of serenity - the opposite of the previous day, when I was in such testing for survival. The Bible reading for that morning had noted in the margin how the Children of Israel were tested in the wilderness, how God had delivered them, how they had sat down and rested by the water of Elim, where there were twelve springs and seventy palm trees. 'When ever do you get to rest?' I had asked myself. As I drifted into dreamless oblivion on the bed, three words articulated in my mind: 'After testing, rest'.

I awoke three hours later, totally refreshed and ready for the battle. Peter was back in the office, and the mail had arrived. Opening the letters for the day was generally a traumatic experience filled with reminder notes and accounts I had overlooked or forgotten. I generally opened first those envelopes that gave any hope of a payment, and left the obvious account notices until last. A large, unexpected cheque fell out of one - the first I had opened. It came from an out-of-town co-operative society and was for two thirds of the total sum it had borrowed on a housing loan. Only about one quarter of the building had been completed, and I had hoped to be paid about one quarter of the sum received during the next week or two prior to the Christmas break. There had obviously been a mistake, which my new-found determination insisted I look into instantly. I phoned the client and offered to return the payment. But the answer came back, 'No, that's the right amount'. This little miracle caused me to start spending the bank loan I had applied for, even before it was confirmed. It would take three days for the cheques to be presented to the bank, by which time the fate of the loan would be known. The next day, more unexpected money arrived; and at nine o'clock the following day, the bank manager phoned to tell me the loan had been approved. 'I have never seen one come through so quickly', he said in an unbelieving voice. It was the final confirmation in my mind that God was indicating His purpose, which was to have me let go the dishonesty of the past in order that He could bless me. The experience was so clear and unexpected that I assumed I should expect to become prosperous. But the fight was far from over. I still had to see the redoubtable Mrs Benedikt with my final accounts - a situation young builders do not relish, even with the most benign clients. I went down to her new house with Peter a few days before the Christmas break. The news was not good. Mrs Benedikt had had an awful day at her Christmas ******* (entire line missing; see bottom of p. 392 of original) ******* her way home and had to wade knee-deep in Bridge Road, Richmond, in full view of curious onlookers. I was in no shape for prolonged haggling over justifiable extras, and my loyal friend Peter was not designed for verbal slugging. He flourished amid quiet decision making, with a little give-and-take on both sides. I had earnestly prayed that whatever else happened at this interview, the whole matter would be settled without argument.

When we set eyes on Mrs Benedikt and her husband, it took all of my faith to believe such a course possible. We ensconced ourselves in the living room (with its newly raised ceilings), were given a drink, and felt chilled by the first sentence of our lady client's reply to our claims. It was not at all encouraging. I answered that this item was one she had ordered and that I had simply done as requested. There was a moment's pause. A slight shadow seemed to lift off of Mrs Benedikt's face. Her voice changed. 'I tell you what we will do, Mr Knox. I will pay this account less £500 immediately. You complete the outstanding items, and I will settle the rest'. Peter and I gulped silently; the discussion was over, and his whisky was only half finished. Five minutes later, they were putting us into our cars and wishing us a Merry Christmas, and our redoubtable client was as affable as someone would be who had never had a difficult or hostile thought in her life.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >