A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 8: Scotch College

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 8: Scotch College

Author: Alistair Knox

Middle Park Central School No. 2815 was a Higher Elementary establishment which included the seventh and eighth grades, the first two years of the high-school syllabus. It had an excellent record both scholastically and in sport - particularly swimming, at which it stood alone. There were three classes in each grade, and every class averaged sixty pupils; so it required strong determination on the part of teachers to maintain effective discipline. Some instructors were known by the cut and style of their whipping straps, others by their voices, and still others by their physical characteristics. In addition, the teachers never left - except in the case of old age, or women being forcibly retired upon marrying. Their long tenure, coupled with the static social climate, gave each primary-school teacher a strong degree of influence over sixty students every year. All of my major teachers - Miss Burke (Infant School); Miss Jinnie Kinnane (Grade 3); Miss O'Collins (Grade 4); Billie Werner (Grade 6); and Miss Fraser (Grade 7) - contributed personally to my education as an individual, despite those enormous classes, and I am grateful to them for it. They were never absent from the school unless they were truly sick, and they did their best to produce a good 3-Rs standard at all times.

My first year with Georgie and Jackie was with Miss O'Collins in Grade 4. We became interested in the girls in our midst, who weren't allowed to speak to us in the school ground. There was the usual bright group, which included a beautiful brunette named Gwen Pickford and a reddish-haired athlete called Phyllis Rabelly. We boys used to walk home along Page Street while the girls proceeded along the parallel Richardson Street, and we would watch for one another on each corner, waving and making signs and declaring a preference for the girl of our choice. I was always a sucker for a pretty face, and Gwen Pickford was a clear first - especially as she had the same name as the first lady of the screen of the era who married Douglas Fairbanks Snr, successor to Rudolph Valentino as a romantic film hero. But Gwen wouldn't countenance me because - as she informed some of the other boys - Phyllis Rabelly (who was nicknamed 'Puss') thought I was the best-looking boy in the class, and she would of course be loyal to her friend. And so my experience with the opposite sex started.

Our next determination was to excel in sport because Georgie hoped to make the football team and needed to train, and where he led we must follow. We took to running to and from school twice daily during the winter months. The distance was about a kilometre, and we all ran together each way. There were some five or six of us including Georgie's cousin - Alan Cartledge - and Alan Schwartz, who lived over the road. The three major figures were Georgie and his two boys; Jackie; and I. My bronchial asthma opposed the desire to improve my wind, and I would finish these runs purple-faced and in paroxysms of coughing; but this was part of the cost of achievement, to be endured without question. I was rewarded when my condition improved after a month or two and I could begin to compete against Georgie with more hope of success. As the longer evenings returned, we went back to playing cricket across Danks Street using a knee guard for a wicket. This involved another group of somewhat older boys including Lennie Williams and his two cousins Eddie and Percy Williams, who lived at the corner of the next lane, along Danks Street towards Armstrong Street. Lennie's father had a horse and dray, and he did not regard us very highly since we rented our house from him and he left his dray there each night. Neither Georgie nor Jackie thought much of cricket, but I had been brought up on the recent successes of the Australian XI under Warwick Armstrong, who flayed the English in two quick campaigns in 1920-21. The Gregory-McDonald fast-bowling duo was undefeatable with men like Kellaway, Mailey Pellow, and others; they developed into a wonderful combination, and I lived and dreamed of cricket and its heroes.

The final results of Grade 4 found Gwen Pickford and myself equal first scholastically - an event made possible through my older sister Isobel, who in an hour or two taught me the rudiments of English in such a way that I could never forget. I hoped I could hurdle Grade 5 and regain my lost year, but I was again in bed with bronchial asthma when the year started; during a month's hiatus, I saw Jackie and Georgie promoted and myself consigned to Grade 5. On my return, I made representations to the head teacher which eventually meant I was placed student no. 60 on trial, in the last possible place.

Georgie and Jackie had now become a force to be reckoned with as we worked as a team. I was absent on the first Friday that the two of them were made the grade's maintenance gardeners - primarily because they had some tools. The next Friday I came armed with a watering can and a fork, and when they rose to go out, I rose with them. A discussion occurred with Billie Werner, the teacher, as to the necessity for my proposal. Both of my companions added their strong pleas for my services, largely because of the quantity of work to be done and the tools needed. Billie finally conceded, and we went out to enjoy our morning of freedom in great exaltation.

When the football team had to go by cable tram to North Fitzroy and Georgie was called from our class, I arose and asked to go as well. 'I can't let you go, my boy', said Billie. 'It's only a practice match'. 'But sir', I said, 'I want to become a good player; I should see as many games as possible'. 'You don't think all those children that go to the big matches on Saturdays will turn into good footballers, do you?' he argued. I countered, saying that I hoped I had more brains than most of them. I could feel the class rallying behind me: after a few more amiable thrusts and cuts, Billie graciously conceded and allowed me to win my first sortie against adult domination in an era nearer to Dickens than to the 1980s. Since I really wasn't a good footballer, and because my main reason for wanting to attend the match was to go on the cable tram and miss an afternoon's school, I gained a new sense of the power of eyeball confrontation, which I have tried to exploit ever since.

The next major school event was the Combined Sports Day, from which we contrived to stay away and conduct our own. We arranged our own meet in our long, narrow, paling-fenced backyard for some events, and ran around the block for distance races and onto the beach for the cross-country obstacle race. This was the major event of the day. We started by climbing through ladders and barrels in the yard, then down the cobbled lane, and along the beach. It was compulsory to run barefooted, which was sensible enough - until near the finish, where the course passed diagonally over a macadamised road composed of razor-sharp gravel that would slow down all but the hardiest and maddest. Although we ran as an easy-going bunch most of the way, we were deadly serious as we approached the sharp surface which led to the winning post at our front gate. We all knew Georgie was the one to beat, but his size and strength made it appear almost impossible.

I took off first on the long final sprint and was so worked up I wouldn't even have noticed whether or not I had been running on broken glass. I could hear Georgie gaining; when we reached the nature strip with five yards to go, we were neck and neck. We hit the tape together, and the result was declared a tie. Georgie blamed the road surface when he didn't beat me, and the others didn't like this freak result because it would put me into a class above them; so we decided to re-run the event on a slightly shortened course to settle the issue - and cut me back to size.

On the re-run, I once again seized the initiative as we crossed a vacant lot before reaching the macadam road surface. Georgie was keeping so close to me to avoid losing again that he stepped into a concealed hole beside the narrow track and lost a few yards. He was once more gathering me in as we reached the nature strip. My strength was finished. The rise in the ground caused me to reel backwards and collide with him just as he overtook me. We came to a sickening halt for a moment, but I recovered first - probably because it was the last thing Georgie was expecting. I leapt for the gate and claimed that I had won. Most of the contestants thought I should be disqualified, but I was so anxious to defeat the redoubtable Georgie that I stuck up for myself while gasping through an attack of bronchial asthma with determined bad sportsmanship. We wrangled all the way down the lane and into the backyard until Georgie said, 'Aw, let 'im 'ave it, then', and the argument was decided in my favour.

That sixth-grade year was a great one for me in every respect. I was establishing my position with my peers and discovering that what one lacks in size and strength can be overcome with determination.

The lower-middle-class society then universal in Melbourne generally, and in Middle Park in particular, made growing up a natural progression of events which never seemed to approach any worthwhile crisis. The future just converged like a straight rail track from two lines into one as it proceeded into the distance. My father taught me how to play a straight bat, and about the finer points of cricket, when he snatched half an hour after tea on the summer evenings before he went to a mid-week church meeting. One felt his loving concern in everything he did. He was the epitome of true living - a man among men, completely fair and just to all the children surrounding us, and generous to a fault. He would buy large boxes of assorted penny sweets, which no other family I knew of had; and the strong and the weak, the young and the old shared in this bounty equally. But the most important attribute he had, so far as I was concerned, was his logical brain and fertile imagination; witnessing them enabled me to grasp the complex issues of life as they confronted me. His true Christian principles were always consistent, and I always knew where I stood with him. He had the inherent ability of teacher - never verbose or technical, just witty , with his conversation full of delicious visual images.

My cousin George, Uncle Jim's oldest son, was ten years my senior and of a scientific disposition. I learned much from him. He became an industrial-chemist instructor attached to the Working Men's College (before its name was changed to the Melbourne Technical College) in the early 1920s, so we shared common holiday periods. I helped him erect an elaborate sleepout, a great radio mast, and other projects, and spent long hours with him in Uncle Jim's workshop. George was fast and accurate in everything he undertook, and later, when he was going to be married, he made all his furniture and finished out the carpenting on his new house at Heidelberg. Between work sessions we played endless games of backyard cricket, which was the one thing at which I could match him. His high-diving ability and swimming prowess made him something of a hero to me, because I was as cautious by nature as he was fearless. The natural manner in which I was brought into 'doing for thyself' was quite unusual. It enabled me to attempt almost any task, while at the same time rendering me unimpressed by standard instructional methods. As things came so easily to me, I generally only half finished them.

Our strong Christian standards meant that I wasn't allowed to go to the pictures on Saturday afternoons, and that Sunday was the Lord's Day. Even more, our social standards were so defined that I thought drinking beer was a mortal sin which would eventually lead one to ruin. I was so immature that I never realised that the smell on Mr. Williams's - our next-door neighbour's - breath was actually beer, or that his red face was heightened by his occupation as a commercial traveller. He had been an excellent sport in his heyday. I would sometimes go with his daughters Alvie and Loveday to the Middle Park Bowling Green on a Sunday afternoon to watch 'Skipper' Williams as he led his rink to victory.

A favourite pastime on hot summer evenings were the water fights which took place through cracks in the paling fence between the Williamses and us. They were great fun: we would hide in the fig trees and pour big buckets of water over the fence, like boiling oil from a castle wall; and our previously-prepared water drums, hidden on the roof, occasionally caused mayhem to the opposition. There might be a dozen or more boys taking part. Hostilities would suddenly come to a stop when Skipper Williams's high-pitched voice called out 'Who's squirtin?!' His small stature would sometimes cause him to be mistaken for one of the water warriors. When he came to the backyard by chance, the protagonists on our side of the fence would lie low, and Skipper would cop a strong jet of water in the middle of his back. Eddie and Percy Williams - Skipper's brother's kids who joined in these activities - shared their father's low opinion of our family, partly because we were their tenants and partly because of our active Christian practices. I was three years younger than Eddie, who appeared to enjoy heavying me and never hesitated to keep me in line with a cuff over the head - something my sheltered upbringing did not appreciate.

During this year I became very friendly with my cousin Alex Knox, who was taller, stronger, and a little older than Eddie. He lived in Alphington, but he came to our place regularly for Sunday dinner and stayed until it was time to return to the Meeting for the evening service. We used to run home the one and a half miles from church together as a training effort; it helped us feel the morning was not entirely wasted. In addition I enjoyed great freedom from the ever-present threat of Eddie, whom I was in danger of running into at any time. Alex was fair-minded and well able to look after himself in a fight, and I thoroughly enjoyed the immunity his presence afforded. One day Eddie saw me in the lane and looked menacingly at me, so I raced inside and viewed him from the safety of the back paling fence. To my delight, Alex came around the corner at that very moment, and with an ill-considered evaluation of my position I begged him to deal physically with the persecuting Eddie. I was unable to stop talking - despite the hostile glare Eddie gave me as he said, 'I'll get you later, Knoxie' - even after Alex had told me to be careful what I said. He gave Eddie a token short jab to the chest to let him know who was boss, and then dismissed him. But it was not the end of the troubles: Eddie Williams was out to get me, and I was very vulnerable the other six days of the week.

Fear overtook me whenever I ventured out alone, and I had to keep an eye out at every corner. Eddie sighted me on a couple of occasions and set off in pursuit as I fled in abject terror and somehow managed to escape him. When he finally confronted me, sufficient time had elapsed to blunt the keen edge of his anger, especially as I had played a very cowardly role; it was a relief to get my perfunctory punching over and done with.

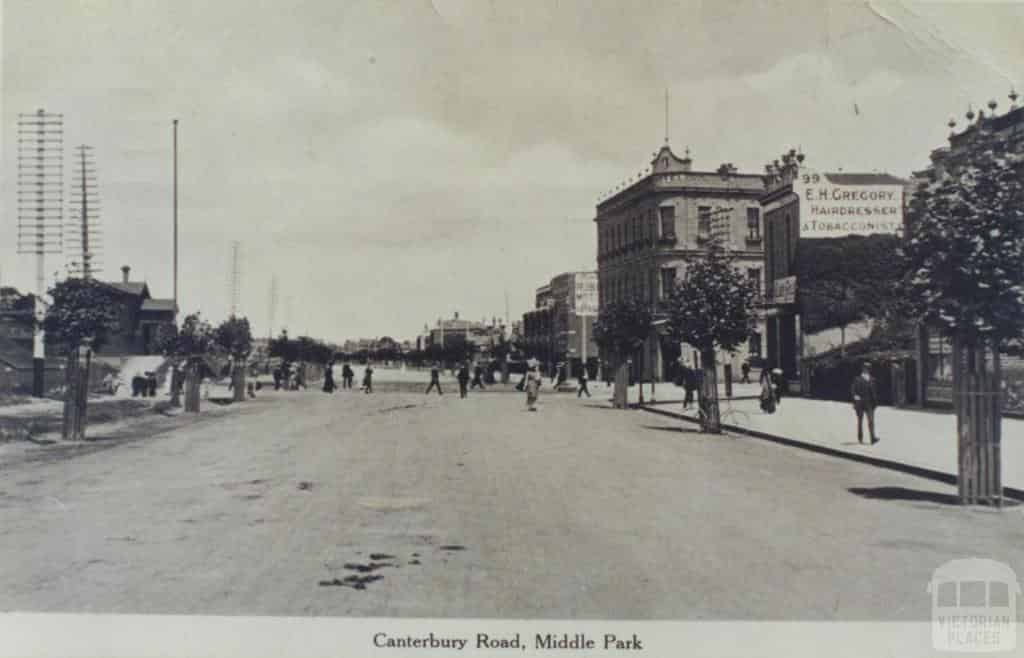

Something we all enjoyed in Middle Park was the sense of space created by the wide streetscapes, with the sea on the south and Albert Park on the north. All of this very much ameliorated the relatively high density of the small housing. The stable, unchanging population produced a social aura different from that of the rest of the city. The ships entered and left Port Melbourne and Williamstown in great numbers, and the periodic visits by Australian and British naval squadrons developed in us a great obsession with overseas travel. The fact that virtually no family could afford to travel only heightened the desire to do so. The great day in 1925 on which the American fleet, comprising more than forty ships, sailed into Port Phillip Bay was a spectacle far beyond anything we had ever seen or would probably ever see again in the bay. We walked up and down the Esplanade, particularly observing the ships' distinctive latticed-metal masts, which were singularly their own; and we spent days on board when the vessels were open for inspection. It was a goodwill visit in every sense of the word, especially with the female sex. The sense of nationhood which had developed with the war was steadily reducing the 'tyranny of distance' that had been our lot since the arrival of the first fleet in 1780.

In 1925 the Victorian education system was much simpler in both structure and aims than it is in 1985. The State boasted six great public schools representing the four major Christian denominations. Scotch was Presbyterian and almost by prior rite the oldest, closely followed by Melbourne Grammar, Church of England, Wesley Methodist, and Xavier Roman Catholic. The adjacent city of Geelong contributed Geelong Grammar, Church of England, and Geelong College, Presbyterian. The two grammar schools had the air of being the most prestigious and Scotch the most scholastic. Scotch and Grammar actually played the first recorded game of Australian Rules football in the 1850s. The goals were placed more than a mile apart, and neither side scored during the first day's play. The battle continued the following morning, and time was declared after one team finally managed a goal.

Behind this front line of six colleges, there ranged a second line of private schools whose fees were as expensive but whose sporting prestige was not as high. The next group was the High Schools, where scholarship was important and sport was secondary. Still further back came the Technical Schools, which had only a year or two earlier overcome the slur of being called the Working Men's Colleges.

Middle Park was a Higher Elementary school which continued for a further two years beyond the ordinary primary levels. At the conclusion of the year, the eighth-grade scholars sat for the Merit Certificate - which was still regarded as a sufficient qualification for a working man.

My parents considered the possible alternatives carefully before sending me to Scotch College. It meant some financial hardship for them, but the real decision lay in the quality of the School itself. My father, who's three years in the Melbourne Grammar Prep, had left him with few illusions about the results to expect - scholastic, sporting, and social - from that institution, despite its emphasis on the classics.

I started in 1925, the last year before the final remnant of the original Scotch College - which had been located in East Melbourne since 1851 - was to migrate to Hawthorn. Several years earlier the major part of the School had transferred to a magnificent sequestered site on the Yarra River. The buildings were of red brick and they looked somewhat brash when compared with the bluestone antiquity and nostalgia of Melbourne Grammar and the old East Melbourne Scotch. When I first saw the school, I was conscious that its buildings were more practical and set for contemporary learning and hard work than the old bluestone piles seemed to be. I accompanied my father for an interview the day before the first term began. We greatly disappointed the vice-principal because my father refused to let me learn Greek and Latin, which were Vice-Principal 'Bumpy' Ingram's special subjects. I was thankful to my father - though for different reasons. He regarded these languages as unnecessary for the new age starting around us, and I was eager to escape the memorisation of useless words. Bumpy Ingram saw these studies as a necessary discipline for a proper education.

The Scotch College Quadrangle

The Scotch College Quadrangle

I arrived for my first assembly in a blue-serge suit, complete with apple-catcher trousers and cardinal cap minus the silver Burning Bush Badge, which arrived a week or two later and completely distinguished the first-year boys from the rest of the school.

I still recall the noise, the dust, and the din from nearly one thousand voices and two thousand feet as friendships were renewed after the long vacation and we were told to sit in random seats for the initial assembly.

There was the traditional filing in of the masters in gowns and mortar boards led by the principal, W. S. Littlejohn, M.A. The sunlight that shone through the high windows accompanied the short service conducted by the principal - the chaplain had resigned the previous year and a successor had not yet been appointed. W. S. Littlejohn, M.A. - universally referred to as 'Bill' - presented a true air of academic authority as he intoned the daily psalm, reading the alternate verses, while the school answered him back in a cavernous monotone in the responsive reading. His pointed, silver-grey beard and short-cut hair were set off by his unusual spectacles and his heavily accented voice, which was as Scottish as Harris Tweed - and nearly twice as thick.

I hardly was able to make out one word he said that first day; but I found the responsive 1st Psalm, which I followed in the book set out for all students, to be of great assistance in comprehending the Scottish language I was to hear for the next three years. A hymn was then sung, with gusto rather than with meaning; and the echoing that issued from the dramatically tall assembly hall echoed in its upper confines for seconds after it stopped - like the sound of a piano that doesn't cut off when it should. As we slouched back in our seats, Bill's voice rose in prayer to the Almighty, Creator, and Sovereign in firm tones. There were times in his petition, however, when one was aware of emotional strain and pleading - which I found reassuring and human.

At the conclusion of this part of the proceedings, Bill would go over the topics of the day and then hand over to Bumpy Ingram, who was to prove an institution in his own right. If Bill Littlejohn's accent was difficult, Bumpy's was quite inscrutable. It was a monotone burr that continued without punctuation, like the growl of a friendly bear from the back of a dark cave. One felt he could have been intoning Latin conjugations in his sleep. He appeared to confine most of his remarks to reporting the lost property which had been handed in to him. We became aware of this because he held up the lost objects for all to see. Through this process of daily repetition, we were gradually able to understand what he was saying, much like South Sea islanders learning English from nineteenth-century missionaries.

The influence of the northern accents, however, became an integral part of our education and continued long after that which told us that the best English accent had become meaningless. What stood out in my mind was the unequivocal integrity of the men themselves. There was no doubt where they stood. They were men of Christian principle in both thought and belief. Although in some ways I viewed Bill as a bit of an eccentric who sometimes missed the boat, he could never be dismissed as irrelevant. Together these men and their qualities reflected the basic differences between Scotch College and Melbourne Grammar School. At the extremes it compared 'the nobility of intent' with the quality of affluence.

The whole notion of school changed immediately. I had to leave home an hour earlier to go by train to Kooyong Station and then set off at a sharp walk to make Assembly by 9 a.m. There were some advantages to this: I found myself travelling with a fairly select group of fellow students with whom I became firm friends. They were - except for Keith and Ian Fleming, whose family conducted a dairy farm on the Yarra flats at Heidelberg - from a more salubrious background than I was, but our family conversation lost nothing in real issues. And the Fleming brothers became famous cricketers and footballers who restored the school to its premier sporting position and defeated the aspirations of Melbourne Grammar despite its sophisticated dark-blue colours.

About four fifths of the school were day boys, who were called 'Dagoes' by the boarders who lived either in Glen or School house near the main entry to the school at the top of the hill. The boarders enjoyed a deeper association with the school than I had any ambition to share, particularly as I learnt the number of hours they spent in doing homework in classrooms every evening. It was an activity for which I had no predilection whatsoever. The first tangible appreciation I gained for the school was the longer holidays we enjoyed. Then I discovered the playing fields, which were commodious and first-class with good equipment available and a sense that it was the best.

One thing my father taught me was how to play a straight bat - as essential to an education as an Arts degree, which I can still appreciate sixty years later. Our household placed no special emphasis on study as being imperative to getting on in life, but I did gain an instinctive appreciation of poetry, which my father could recite for hours on end. I was assigned to Form IVD. The form master was 'Devil Said' Wilson, a kindly, grey-headed, mathematically minded man who caused no ripples in the school life. There was 'Wog' Trounce, the English master, a rather aesthetic character who introduced me to Shakespeare through the medium of Shylock and the Merchant of Venice. I mentioned to my father how I liked reading Shakespeare, thinking he would approve, but I was rather surprised at his answer. He said he could never read him but that he had in his youth in great secrecy gone to see some Shakespearean productions and loved them. He went on to eulogise Shylock as the real hero of the play, criticised Portia as sanctimonious, and laid out in one blow the basis of a true evaluation of literature.

It would have been a serious matter had my father's parents known of his fragmentary theatre-going; they would never have attended a play - because of its worldliness. Even in 1925 I was not supposed to go to the silent films on a Saturday afternoon, but I inched into that practice by small degrees and various subterfuges. The changes that were to engulf us in radically different lives were just beginning. On reviewing what has occurred in the ensuing sixty years, it is inconceivable that it all could have happened so quietly. There had never been another such period in the history of mankind. In 1925 a Christian ethos covered our lives in public - whatever we may have thought individually - despite the capitulation from creation to evolution. Some things were right, others wrong; some white, some black. Almost every person would have had a knowledge of what the Bible taught, whether it was agreed with or not. In the law court, divorce was hard and tedious to substantiate, and the main justification was adultery. In 1985 adultery is not a cause at all.

The 1920s Jazz Age had burgeoned, and Hollywood screen moguls were laying the foundation of a new order of social freedom; they would divorce annually based on human convenience alone, although it did take a decade to bring about the demise of the Hayes Code and finally allow films to show a husband and wife together in a double bed rather than, as previously, sitting up primly in separate beds divided by two sets of bedclothes through which neither man nor beast ever could have passed.

Then there was the annual medical lecture, given to the entire school assembly by the white-haired school doctor. He would skirt around the subject of sex and its abuses for some minutes, get confused over the difference between mental and physical hygiene, and finish up rather hot under the collar. His red face, white hair, and black suit made him look slightly like the imperial German flag. There was a sense of relief from both masters and boys as he concluded: this awkward matter could now be returned to obscurity for another year, and we could all return to our private thoughts and aims without molestation from the outside. We were caught in a web of sexual silence which was interspersed with suggestive sniggers, sly looks, and an unending flow of 'dirty' jokes in selected company, all of them eventually to play a major role in our social activities.

Our conversations were stratified into sacred, secular, profane, and depraved, and our vocabularies and conversations adjusted without much effort to fit the mood of the listener. I was particularly subject to these limitations of verbal communication because my own family's conversations were truly considered, and set on a high course. Swearing was never tolerated, and suggestive connotations were entirely absent. Nor was it a matter of mere social expediency for the sake of the family: they had retained something of the Puritan singularity of attitude because that was how they actually thought. They had to face the conditions around them which were subject to the decade, but they did this without compromise; yet they were still able to discern between subtlety and sanctimony, between humour and banality.

I found myself spending every afternoon after school on the upper oval practising with the Under 15s cricket team. The backyard and across-the-road cricket pitches of State School days were quickly translated into a dream world of turf wickets, green grass, and leather-covered cricket balls and the hypnotic sound produced when they came into contact with the willow of the bats. I donned pads and gloves for the first time and could feel the transition from boyhood to manhood take place within me immediately. I became friendly with the two or three Middle Park families who had sons going to Scotch and Grammar, and we formed a coterie by virtue of the time we spent together swimming during the extended Christmas holidays we enjoyed over the State School boys.

Freddie Finlay went to Scotch, and Clark and Ivan Rowell were Melbourne Grammarians. Freddie's father was an ageing golf professional who still taught the game in Albert Park by day and fished for schnapper in the pre-dawn waters of Hobsons Bay when the conditions were right. He was an expert, with long experience in catching these large, delicately-flavoured fighting fish. He knew all their moods and habits. When the temperatures rose towards the century and the winds turned to the north and blew offshore - these were signals to him that it would be useless to row out to his favourite reef, because it would be deserted. The quarry would have sought another hiding place until the wind returned to the south. But the hot night had the opposite effect on Freddie, the Rowells, and me. We knew it meant we could have the boat in the early morning to row out to catch the innumerable flathead which would place themselves on our hooks and make no demur as we hauled them aboard. On some occasions they offered themselves like infidel sacrifices, two at a time.

In the evening, before our fishing excursions, would go to buy cakes from Benton's Cake Shop in Armstrong Street; this was possible in 1925 because of the altered closing times. We would then rise at 3 a.m. and meet in Freddie's back lane, conversing in loud whispers so that the neighbours would not be disturbed as we ran the boat down the cobbled lane into Harold Street and onto the white sand near the drain at the end of the road. As soon as the cast-iron wheels hit the bluestone-cobbled laneway, any reason for silence became superfluous. The racket of trundling wheels would reverberate , bouncing from side to side off houses built right up to their boundaries with bedroom windows facing the right-of-way. From within those rooms the noise would have been of the calibre of cannons being discharged in the 1812 Overture. We lived in a peaceful place in a peaceful time, and this untimely disturbance of the quiet would cause a slight sense of apprehension which only added to the exquisite thrill of the hot night air fanning our bare backs and the cool water caressing our legs as we launched out into the starlit sea. The following wind would blow us out quickly, and we would move in silent anticipation until we got certain shore lights into conjunction over a reef that would suit our purposes. Flathead were on the lowest rung of the fish social order in Hobsons Bay, and, of course, they had no appreciation of the subtleties of pisciculture that affected their snapper overlords. They would bite at any time, and their flesh tasted just the same as any other to we who were not indulging in fishing as a gentle pastime. We were experiencing the first flavour of being responsible for our own safety, of becoming our own men. We had known the local coast all our lives and had witnessed the occasional drowning or rescue common to all seaside areas, so we understood the rapid changes which could occur when the offshore wind increased with the coming daylight, and how difficult it might be to get back to our original starting point.

Also, there existed the remote possibility of sharks - to be kept in mind when we considered slipping overboard for a swim in the welcoming water which still glittered with the reflection of the waning stars. Our anchor would drift off the reef onto the sandy bottom and allow the wind to drive us steadily out towards the main channel, which was fraught with the combined dangers of deep water, unpredictable currents, and passing shipping. It was a classic example of what I have so often encountered: trying to decide precisely when the fascination of adventure and self-determination needs to be controlled only by common-sense survival. My romantic bent of mind always wanted to ignore the gradually increasing danger for just a little longer, in order to extract the ultimate moment of experience. I was growing into manhood from strong forebears who appeared to have understood both sides of the challenges of life, and who had determined that the good would dominate the bad for them, regardless of their desires or feelings. Their intentions succeeded: first, because they were real Christians who had been 'saved by grace through faith'; and second, because they were a united family who put 'the Kingdom of God and His righteousness' ahead of their own ambitions. It was their fathers' determination - to step out into a life of faith and trust that their God would also provide for their daily needs - that bore spiritual fruit in their families' lives. Any of the privations of childhood would later be outweighed by the advantages they finally enjoyed by not having attended school until they were eleven or twelve years old. Just like antipodean King Davids, they fought out the crises of their emerging beliefs under the stars and the silent, moonlit night of the Yarra Valley. They may not have delivered lambs of the flock from the paw of the bear - or from the mouth of the lion, like the ancient patriarch - but they were coming to understand the meaning of their lives as they learned simultaneously from the living and written word of God properly understood and creatively applied.

I had also inherited great spiritual blessing from my mother's side of the family through her father, Grandpa Brown, who had lived out his spiritual life in the response of faith and action. Being her favourite, I was overindulged by a remarkable mother who believed I could do no wrong. Both of my parents balanced their deep compassion with a discernment of the opposition of good to evil, though they did tend to give me the benefit of too many doubts; I would take full advantage of this, and it later interfered with my ability to make hard decisions. I never possessed the singleness of resolve which they did.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >