A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 9: Tired of school

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 9: Tired of school

Author: Alistair Knox

The new society which evolved after the First World War affected the national lifestyle and precipitated a decline in moral standards. The promises of a new world failed to fructify in many instances because every participating country, irrespective of having won or lost, was so exhausted and changed that a world-wide skepticism of traditional authority and values ensued. The failure of Woodrow Wilson to prevent the American withdrawal from the European peace treaties; Britain's failure to look for a new deal for its working class; and France's determination to make the defeated Germans pay dearly - these laid the foundation for a new society that would contain elements both of Teutonic totalitarianism and Russian communism: these would never again disappear.

While Australian servicemen generally received far greater repatriation benefits than did those of other countries, there was still a wall of bitterness against the Soldier Settlement schemes, which saw many ex-war heroes deprived of the ability to survive on the land because governments either would not or could not fulfill their promises for the new emancipation.

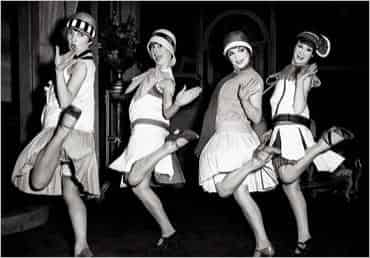

Seeking some relief, the world had turned to the Jazz Age, the shingle hair cut, the Black Bottom, and the Charleston. Germany's intense inflationary period, along with the collapse of its mark, added to these factors to produce a new society that broke down most international boundaries. In my own life these cataclysmic changes affected only my boyhood stamp collection - I now possessed some unused five-million- mark stamps - but I was aware that the age of change had arrived. Pleasure had become the substitute for accepting the shortcomings of the present in the hope of a better resurrection.

Dancing the Charleston

Dancing the Charleston

The large Sunday school attached to our Meeting in South Melbourne had been decimated by the postwar Spanish influenza epidemic, which generated a great fear among whole societies and closed down many institutions where people congregated altogether. As the fear finally dwindled, it became much easier to redevelop places of pleasure than of discipline.

The Establishment had lost its respect: no matter how much it returned to prewar institutions, archaic uniforms, and grand parades, it had no answer to offer the countless millions whose countries and lifestyles had vanished. A new pragmatism was sweeping the world in a thousand different ways at the one time. Where I had once lived in the mainstream of society, I now felt myself to be outside it. Church attendance fell away; and the general observance of the Sabbath - which had been maintained from the beginning of the Reformation and beyond - disappeared step by step as men lost their faith in the Creator God. I still went regularly to the Meeting each Sunday morning because my parents went; their attitudes made it right in my eyes. They had no doubts, and their certainties were reassuring to me.

One major change in my life was that our large Sunday school had vanished - decimated by the Spanish infuenza epidemic, never to return. I generally walked to and from the Temperance Hall in Napier Street every Sunday morning - a distance of one and a half miles each way - without complaint, though I felt that having to do it again in the afternoon was too much.

Uncle Jim - who was my Sunday school teacher - was a man I admired greatly for his consistency and hard work, but as I grew up I found his teaching methods increasingly repetitive and boring. I had enjoyed my father's ability as a raconteur for far too long to be able to accept any unimaginative approach to learning. During my first year at Scotch, I told my father that the afternoon Sunday school was doing me more harm than good. To my surprise, he took my part unequivocally, despite Uncle Jim's disappointment, and I never went back. Instead I would attend the evening services, which were an entirely different matter. There we heard gospel messages - 'addresses' - given by the men who formed the inner nucleus of our congregation, but principally by my father. It is amazing how my father is still visible in my mind's eye sixty years later - how what he said is still as valid now as it was then. He infused his fine diction and choice of words with an emotional timbre. Though he seldom spoke for more than twenty minutes, his sermonising of scripture was so effective that some of it still remains in my mind. He believed in he must never gesture with his hands when he spoke. To prevent his, he rolled up his cloth-covered Sankey's Hymn Book in two hands as if it were a little scroll. He taught me what commitment was - and what it means - but, of course, he could not make me accept it; that had to be my decision. I told him I had decided for Christ; but my decision was more of the mind than of the heart. I felt that attending church instead of playing sport on Sundays - I was giving up my own legitimate choices for the sake of belief - meant doing what I was expected to do, especially since any inner conviction for the choice was absent. I was substituting good works for true faith, and not changing because of what the faith would commit me to. It was all difficulty and effort without joy; the commitment of the heart was not involved.

The year 1925 also saw the first cardinal changes in me, from childhood to puberty and the discovery of sex. My knowledge of that secret world was nil. I had not even contemplated why the sexes required different organs, or where babies actually came from. I did not believe it possible that my parents would indulge in a vulgar activity like sex. All those innuendoes I heard at school could not be right. I never received any sex education other than from the Bible, and I did not even understand most of that. So I was launched into life in total ignorance. Occasionally I would become moonstruck on odd girls for indefinable reasons. The remainder of the female sex did not worry me. I believed those choices I had made were extremely good-looking and individual. I found it hard to be natural, because my instincts ran deep and I would become inordinately jealous when these girls looked sideways at anyone else. It caused me to set impossible and unnatural standards both for them and for myself. It was starting to affect my whole attitude toward life and inwardly divided me. I had no difficulty attracting girls, and should have enjoyed them. Instead I became either far too reticent and shy or, conversely, too quick and overt. I simply lacked the confidence to maintain a broad view which would see things whole and see them clearly. I was becoming more anxious to have relationships with females at the same time that I was becoming too introverted to promote them.

The year 1925 passed from summer to winter, and I found myself part of its complex life. I took part in some of the school excursions; but I was never adventurous enough to go to Walhalla for a camp, or by horse from Bairnsdale to Mount Kosciusko for long Christmas holidays, and consequently I missed some of the school's best offerings by flunking these challenges. My old Middle Park friend Johnny - no longer 'Jacky' - Lerew started the following year. We remained friendly, but the old days had gone. He was good at maths; I was hopeless. I came back on English, though I did admit his ability to comprehend algebra and calculus, two subjects I found quite incomprehensible.

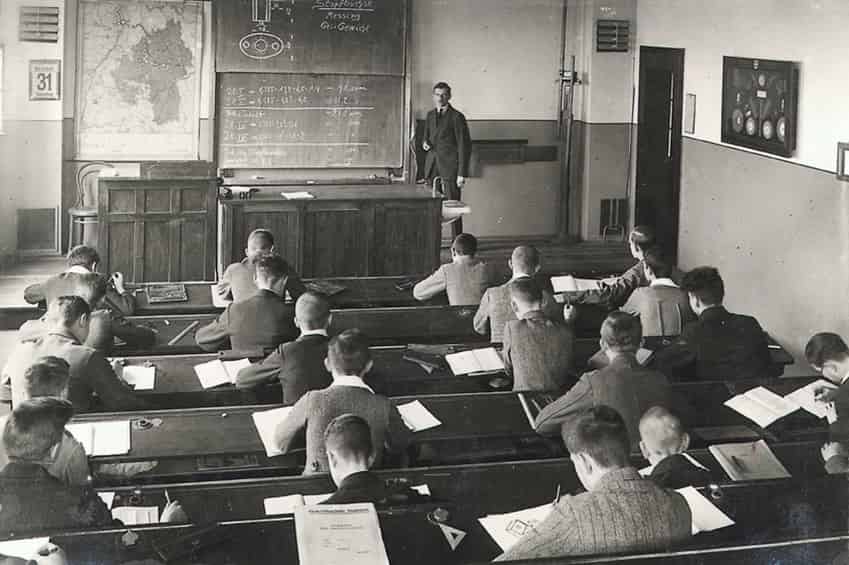

A classroom in 1925

A classroom in 1925

In 1926 my form master was Charlie Moscrop, a notable maths coach, who tried to make me understand the simplest mathematical propositions, with absolutely no result other than to confuse my addled brain still further. Charlie was a nice man with a lined, sallow face; slight stubble; and an unruly head of hair always in need of a trim. He wore new moon-shaped glasses over which he looked at me in frustrated despair with his bloodshot eyes, seeking some sign of sanity on my face. It was a vain search. After some months he decided that a few of us were not serious and were having him on. He felt his teaching was so clear that there could be no other explanation for our failure to learn. One afternoon, he wrote a note to Bill Littlejohn with great deliberation, accusing us of constant inattention and carelessness, of no desire to learn or improve. As we read the note on the way over to the principal's office, we were struck by the injustice of these remarks. I genuinely wanted to learn, as did my companions-in-arms, but Charlie Moscrop - celebrated master though he was - did not understand our needs or how to teach us. Bill had not turned up by the end of the first period, so we returned to Charlie in some hope that he might relent. 'Go back', he said. At the end of the second period, we were still waiting but were told to go back once more. When Bill appeared a few minutes later, he read the note and looked somewhat dark and brooding. 'I take a serious view of this', he said, and marched us into the office, where he made a careful selection from among his canes. This was a serious situation. He alone used the cane at the school, except for the prefects who were at times - and only after a formal, courtlike proceeding - privileged to lay stripes on the backsides of recalcitrant boys a little younger than themselves.

Getting caned was always something of an occasion. My experience of it - I had only been present when canings had been administered; I hadn't actually suffered it myself - told me it would be relatively painless and short-lived. Bill would usually administer five or six strokes in quick succession, and it was all over before it had really begun. I decided to let Jimmy Gillam go first because he had a rounded bum, and also because Bill might tire a little attacking that satisfying target. Nothing was further from the case. He administered each cut separately like a champion golfer using a driver from the tee. He paused between strokes, resumed his stand with great deliberation, and then struck again. Gillam had guts. He stretched over the arm of the leather couch and waited. I could see him flinch for a second after each whack, and observed with considerable consternation how much dust Bill was able to extract from Gillam's blue-serge trousers. He stopped at the sixth stroke and called for the next culprit. I had seen enough. I couldn't bear to watch another suffer, so I took up my position. I can still recall the thrill of pain and agony of that first stroke; but I managed to endure two more before I had to stand up for a few seconds to get my second wind. When it was over, the pain persisted unmercifully. The third member of our party was obviously as mystified about his dilemma as I had been, and the sight of suffering seemed to have reduced his capacity to endure. He cried after the first two cuts, and then tried to stop the third with his hand. It only produced a great wheal, which Bill said didn't count. When the victim arose after his six, Bill signed our note and we walked back to class across the quadrangle. There had been no need for him to sign it, though: our aching bodies bore the indelible signature of a man who had performed his duty diligently. We had to stop for a minute while we staunched our mate's tears; once back in our classroom, we gingerly sat down and tried to look as though nothing were the matter. It took months for the four red lines across my buttocks, and the corrugations they caused, to disappear. The caning did not improve my maths, but I was able to discontinue them at the conclusion of the school year. I don't think it was bad as a one-off reminder of how the world can see things differently than we ourselves might, and as a lesson to be careful that we not allow the same mistake to happen again. It also reinforced my view that Bill Littlejohn was an academic who, though he sometimes missed the boat, had strong and uncompromising principles. The one unforgettable remark he ingrained in my mind came from Psalm 15 in our Assembly response reading: 'He that sweareth to his hurt and changeth not'. He would look up and reiterate the words with vociferous fire and emphasis each time we encountered it, and would then emphasise the message by throwing his Psalm book onto the pulpit cushion. This described the essential man: strong, stern, and not openly compassionate; somewhat superior; and, at times, off the beam. We gave him respect for his strength of character, and put up with his shortcomings.

My scholastic abilities tended to deteriorate in my third year at the school. I obtained my intermediate after sitting for only two supps, as I felt the demand for more effort was essential if I meant to go on the following year. I could not see any sense in it. I had no ambition to succeed in the business world because in those days, everybody I knew worked industriously every day - whether they were rich or poor. Because my family had never placed great value on worldly success, I took after them without much thought. Everyone in Middle Park appeared to take a relaxed view towards an entire life spent working from Monday to 12 noon Saturday. There was the sea and the beach in summer, and the park in winter - these gave the sense of openness despite the small frontages. We all firmly believed that it was the best place in the world in which to reside. Most of what we knew about what was going on overseas came from watching the mail steamers which visited regularly. Australia was, in reality, a remote backwater which felt secure in its isolation. We were all like the man from Kansas City eulogising its qualities. He sang, 'Everything's up to date in Kansas City. They've gone about as far as they can go....'

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >