A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Author: Alistair Knox

We rounded Cape Otway that night, and the following morning we were heading up Port Phillip Bay. When we berthed at Gem Pier men came over from the naval jetty, which we had left behind only a few days earlier, to greet us. We felt we had been away ten years! Two days later we set out for Sydney, where we were to do a refit. Here, at last, was the sea life I had dreamt of. The first conflict with the skipper occurred at Woollongong, where Don and I stayed talking to some WAAFs on the jetty when we should have been aboard. We were directed into the wheel house to the order 'Off caps' and questioned about having been fifteen minutes adrift. It was all too much for me and I wanted to take a swing at the skipper, but Don inserted himself between us and the skipper finally said 'Dismiss. Don't do it again'. The next morning we went through the heads and the boom that bridged Sydney Harbour since the sub attack and on into Rushcutters Bay.

Merioola, a celebrated guesthouse run by Chicka Edgworth

Merioola, a celebrated guesthouse run by Chicka Edgworth

I tried to stay at Merioola, a celebrated guesthouse run by Chicka Edgworth in Kings Cross, especially as my ex-girlfriend Peg Lord was living there; so was the well-known painter Elaine Haxton. But Chicka rather wisely said she was unable to accommodate us, so we arranged to stay aboard; when they put the ship on the slip we lived there for more than two months, during which time we recaptured our lost youth. It was a glorious interlude, guaranteed to cure any middle-class recollections. We went into Sydney every afternoon, down to one of the Cheer Up Huts and the hostesses, and then - often a little inebriated on that uncouth Sydney beer - returned to the ship. Each man reacted in his own way. Don Deany, the pillar of Savings Bank respectability, formed an attachment with an AWAS who was on the shore batteries at Woollongong. Norm and Pat Malone were quiet workers who were fairly harmless, and George Sangster picked up with Francine, a sailor's friend about whom we had heard great stories. I made sallies at anyone interesting but was always prevented from getting very far with them, as though I were being protected by some unseen hand. And I knew very well who that was! On Sundays we would all go around the harbour on ferries. There was one little Italian girl I became interested in, and I arranged to meet her again the day after; but she told me over the phone that her big sister said she wasn't to see me no more. And in those faraway days, older-sisters' commands were law. At the thought that my 'innocent' attention could be so misunderstood I started writing a letter of farewell to the fair Theodora...

Fair Thea what's all this about,

` This firm decision made without

A word to me, to relegate my future

To the dark broad mists of doubt?

Allowing me no hope to nurture,

No embryonic scheme to cherish,

I am left alone - alone to perish,

While you remain immutable

For all the dark unscrutable

Emotion in your eyes, where a slow fire

Simmers, underneath a suitable disguise

Of proper feminine desires.

How sad about your Roman sister,

How said that I had never kissed her!

For if I had, she would not think

You on the cataclysmic brink

Of life unleashed and full of wine.

Our touching lips would interlink

To find a communal design,

A mutual understanding feeling,

Of why we find you so appealing

For you are young and full of years,

Deep with joy and mutual tears

Your life lies wide before.

We know how quickly they take wings and go,

And how uncertain all appears,

Until you cannot start recapturing,

Those transitory joys enrapturing.

Perhaps it's this that makes me sigh,

And precludes that I should try

And act as I had acted when

Youth with high revolving ken

Bade me to conquests or to die.

Fair Thea, you are most disturbing

But life's lost years are too encurbing.

I never heard from Theodora with the smouldering eyes again. It was wartime, and there were no tomorrows, no yesterdays - only todays. The Theodora incident kept me true and sensible, especially when I thought of Mernda and our three lovely children - Tony, Gabrielle, and Eugenie. In addition to these diversions, I had to organise a revolution to oppose our skipper, against whom we bore imagined grievances. We all put in for a draft off the Martindale, and the inquiry conducted by a couple of NAP part-timers brought us all a week's leave and restored us to a democratic society. The skipper was an exceptionally capable seaman, but he lacked sufficient experience to deal with men in wartime conditions. The punctilious obedience of orders - so essential on ships and the fleet, from destroyers upward - gave way to a family situation on ancillary vessels when the ship's company became an organism instead of an organisation. Finally the skipper took a week's leave himself, and we all had the best wartime experience possible, a time of all care but no responsibility.

As the Sunday on which the Skipper was due back dawned, we all felt depressed. Sunday dinner in port was usually something of an event, and Don volunteered to cook while Norm, George, and I went over to the Rushcutter depot canteen for a drink to lessen our sorrows. We stayed longer than we intended to, drank more than we needed to, and became very morose. We finally returned on board to find that Don had prepared a great feast of meat, peas, beans, and potatoes in abundance, with dishes of prunes, jelly, and custard to follow. This manly fare encouraged us a little and as we sat down, Norm asked me for the bread. I threw a loaf across the table to him; he caught it and immediately returned it as hard as he could. I caught it and returned it with all my force. Norm rose as he grabbed it, and kicked it up in the air like a rocket. George, leaning over his food, laughed helplessly. The bread hit the deck head and ricocheted back to the table with great force, landing in the middle of the prunes and custard and jelly. In one instant, we saw George's face turn greenish-yellow as he received the whole dish front-on. Only his glasses gave any evidence there was a human being underneath. Within a couple of seconds every dish was being hurled across the mess deck, and mayhem reigned as jugs of custard were poured over the nearest head and chops and peas and gravy trickled down our fronts. The pandemonium continued as we rushed up on deck armed with pounds of butter, tins of jam, and any other flexible food. It was all over in only two minutes, but the result was unbelievable. As our pent-up tensions dissolved, we surveyed what we had done and were grateful that the skipper had not returned on time. Every minute's grace would allow us to restore a little more order to the chaos. We worked for hours like true Williamstown depot ratings anticipating Saturday rounds. By late afternoon, order had been restored, and we were cooking another dinner and living our accustomed routine once more. When the skipper returned after dark, he would realise that any fears he may have had about possible insubordination during his absence were quite without foundation. We were all thoroughly exhausted and totally amenable.

When the Martindale was returned to the water, there was still much to be done to the ship. She had been transformed from a millionaire's pleasure craft into a good likeness of a real pint-sized fighting ship. Her tall main mast was replaced with a Twin.5 rapid-firer set in a swivelling gun mount which would probably have caused more damage to us than to an enemy aircraft in any worthwhile seaway. A flying bridge was installed on top of the large wheelhouse, and sundry machine guns were mounted at strategic points around the deck. Her whole line and character had undergone a complete change, and we felt very proud of our handiwork. New fuel tanks had been installed in the engine room and under the mess-deck table; they extended our range from thirteen hundred kilometres to four thousand, unprecedented in any other small craft we had ever heard of. Our top speed, however, remained a sedate nine knots; this meant we were able to travel at full speed for twelve days without refuelling - and thus remain a sitting duck the whole time if we were to encounter enemy action.

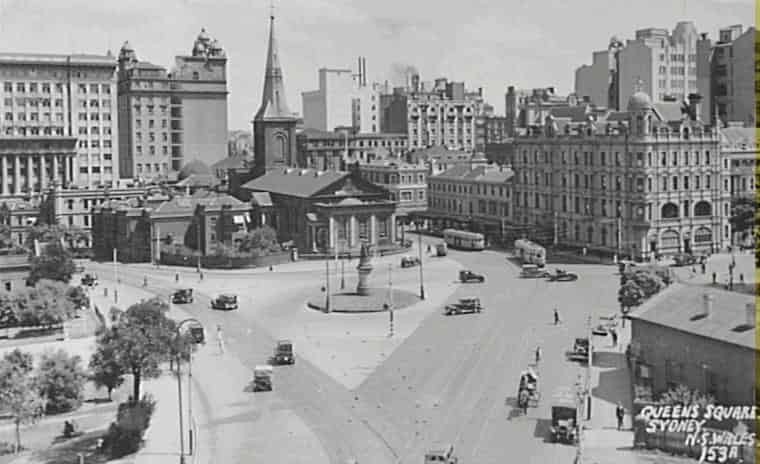

Queen's Square with St Kames church, Sydney_c1930

Queen's Square with St Kames church, Sydney_c1930

I became more aware of the beauty of Sydney, its harbor, and its old buildings as we drove to town in the tram. The St James Church at the top of Macquarie Street often prompted me to get off and make an inspection of its proportion and its brickwork, its sense of beauty and completeness; but it was not until I was looking at it from the centre of the road (which it was possible to do in those almost carless times) that I captured its real spirit. I turned face-about to look at the old Mint opposite and suddenly become aware that I was on the axis of the great Greenway Macquarie Square, which was to become the centre of this great city. Both buildings spoke to each other as they had since 1816, creating an extraordinary sense of contained space. It was the genesis of my architectural career and understanding. In a single bound, my sights were raised from single structures to a new sense of visual totality and comprehension. In addition, I discovered that Greenway was in the direct line of Repton and the great eighteenth-century English Landscape tradition. I saw in the St James Church a combination of impeccable proportions and the understanding of light and colour of buildings. In much the same way as Burley Griffin had responded to the strong Australian sun, the folding light and shadow of Greenway's brickwork had evidenced its great impression on him. Once again, I saw how my future was being prepared for me quite independent of my own thoughts.

I would with great pleasure have spent my entire war service in Sydney had it not been for the fact that I was quite out of money. We only needed a minuscule amount to finance our recreational needs, but a £1 a week does not go far in any man's language. Don's AWAS was in Woollongong, and I moved casually between pleasant females without forming any attachment to them, except for one who turned out to be a good-looking relation of Mo Machachie, the famous comedian. She and I managed to keep our relationship above-board by going skating and enjoying other harmless pursuits together. But it all took a little money, just enough to drain my meagre resources. I managed to borrow an odd 'quid' from softhearted Don, who never complained, no matter how badly he was treated. The agony between the poverty of the staying and the getting-going with our time up north gradually started to make me turn towards getting away. The major work remaining to be done on board was the installation of the new fuel tanks, a fidgety and detailed task. Because the older of the two plumbers who did the work was an ex-South Melbourne football supporter, we soon became good friends. He was also very fond of roast pork, which had been unobtainable for civilians in Sydney for months but which we could get at any time. I arranged to do his work on a Saturday morning so that he could devote himself to preparing a roast. He responded to urgent inquiries from Garden Island officialdom, anxious to know when we would be ready for sea, with three simple words: 'I don't know'. He would then come back to us and ask us when we wanted to leave. We settled for 1 July. And he was as good as his word. We slipped our mooring at precisely 8 a.m. on that date. The day before, I saw the skipper and George approaching in a launch. When they came alongside they told us they had brought a beautiful new auxiliary motor, something we had sought unsuccessfully for months. We placed it on deck, planning to install it as we went up the coast. The departure was a comedy of errors. We had sent George and Pat ashore to get a box of butter; it might be our last chance for such a luxury for many months. The skipper was anxious to make a smart getaway because he was worried about being under the critical eye of a very 'pussa' group of officers looking for faults as they scoffed their eggs and bacon in the ward room. Every day, in every naval establishment, there occurs at precisely 8 a.m. a bugle call which brings the depot to a 'still': all ratings below the rate of petty officers stand to attention and face the flag while those above that rank salute the colours as the flag is sedately raised to the masthead. George and Pat had not returned with the butter, but we had to cast off at 8 a.m. instead of leaving three minutes later. The skipper put the nose of the ship quietly into the jetty to await their arrival. George and Pat finally appeared, on the depot parade ground in the midst of the colours ceremony, and when they saw us underway the bugle call for the drill still had no effect on them. They rushed across the middle of the parade ground and headed up the jetty in pandemonium, struggling with the box of butter in a most ungainly way and in contradistinction to every naval tradition. As the ship's nose touched the jetty, the skipper signalled 'Slow astern'. Don, in the engine room, made one of his very rare mistakes. He mistook the signal and went slow ahead. The skipper rang again 'Half astern', and Don responded by going half ahead. The ship's momentum was beginning to shake the wharf with the increased power. The skipper quickly rang 'Full astern', and Don obliged by going full ahead. The skipper leapt down from the flying bridge and shouted to Don through the hatch, 'What the hell are you doing? Go astern - not ahead!' At that precise moment - with the butter about to put on board - Don reversed direction and we shot back from the jetty still minus two men and the butter. We had completely lost our naval composure. The correction was quickly made and we eventually swung way from Rushcutter to enter the main harbour. In a couple of minutes, we had rounded the point past Pinchgut and were passing under the bridge.

The cold wintry air and the sound of the Gardner motor purring contentedly as it settled down to its work restored our poise. As we passed Middle Harbour and felt the ocean swell rising, a sense of elation set in. I watched a small vessel entering the heads as we went out. It was still heaving with the sea we were about to enter. A rating came on deck with a breakfast tray and made for the wheelhouse with carefully balanced steps for whoever was bringing the ship into port. As the seas started to rise and fall with their accustomed vigour I heard Norm, who was on the wheel, repeating the skipper's command to change direction 25 north, and I knew we were underway at last. Uppermost in my mind was the question of whether we would ever again return. In those days, the first of July was the nightmare day of the year in the bank. Interest had to be added to all passbooks, and there was a series of complicated balances to be resolved that would keep us working back each night for a week or more. The wintry scene outside the heads kept thoughts of men and women toiling away in an office as remote from my mind as I could wish. We divided into three watches of four hours on and eight off. Norm and the skipper formed the first; George and Don the second; and Pat and I the third. The great joy of keeping the course on the log and noting every passing vessel and land feature proposed our way with good success. Keith Collison, the cook, did not keep a watch and Ross Gourley, the eighteen-year-old telegraphist who had just joined us, had a schedule of his own. The seamen kept the parts of the ship clean, and the early-morning scrubbing of the decks proved a great experience, especially to the Williamstown-trained ratings.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >