A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Author: Alistair Knox

My father-in-law Reggie Clayton died in 1940, and I inherited his 8-horsepower square-nosed Fiat tourer, along with a small petrol ration. It was the first motor vehicle I had ever owned. I had only been outside Victoria once in my life, when Mernda won a competition having to do with fashion and style - skills at which she exhibited remarkable talent. No doubt a good French background on one side, heightened by her Spanish exotica on the other, contributed to her success in the contest a few months before the war began. The prize entitled us to a holiday cruise extending from Tasmania to Queensland and back. I had at last succeeded in getting a ship's deck moving under my feet and experiencing the thrill of sailing through the Sydney heads at 7 a.m. In those days relatively few people had cars, and even most of those who did had put them on blocks for the duration of the war.

1935 Fiat 1500 A

1935 Fiat 1500 A

Reggie Clayton, however, had spent all of his long school holidays in the later stage of his life touring around the Australian Alps and along the southern coast of New South Wales. On its little back seat his vehicle carried, among other paraphernalia, two equipment boxes painted green and orange, and an auto tent which made camping quite easy; so Mernda and I decided to drive to Merimbula by the sea in New South Wales for our annual holiday. We took Tony - our first-born, who was approaching two years of age - with us and left Gay, our eldest daughter, with Mernda's mother.

In my ignorance I took the Hume Highway, only to find when we bought a road map at Wangaratta that we should have followed the coast road hundreds of miles to the east. We drove as far as Tarcutta, where we spent the remainder of the night sitting up in the car. With the new day we set out across the Monaro Highway, in the footsteps of the early mountain men, to Guilford, Tummut, and the foot of Talbingo, but somehow always evading Tumbarumba which was as an unfulfilled dream. It was all wonderfully remote. We were warned to bring water for the radiator against the steep climb which would carry us quickly to the roof of our private world. The roadway was only wide enough for a single vehicle. Had we met anything head-on, one of us would have to have reversed for miles in order to find a passing loop. We encountered some small bush burning and snow simultaneously.

At the end of the day we arrived at Rule's Point, one of the highest altitudes; we decided to stay at its one inhabited house, which happened to be the postman's dwelling. It post was run by a true outback Australian bushman, who delivered the mail by packhorse to the isolated settlers once a week. I once again became conscious of how often events had followed the course designed for my life's work; it was being prepared for me without my awareness. As we all sat watching the white alpine-ash logs blazing in the stone fireplace after dinner, our host, whose name was McDonald, told of the royals and other VIP visitors he had guided around the high plains, which had been the home of the Snow River mythology and Clancy of the Overflow. He whetted my appetite as he recounted great races of earlier days and promised to show me the race course the following morning. We awoke the next morning to see a landscape consisting of peaks and saddles which varied in height by hundreds of feet. I saw absolutely no sign of any official race track or sporting impedimenta which would have backed up our host's claims. 'Where did they race?' I asked in complete disbelief. McDonald pointed out a small, level area half a mile away and then led our eyes from feature to feature through the snow-flecked landscape until he had completed a circle more than a mile long. The whole area had once been a race course on which the premier horsemen fought out the mountain supremacy.

Mernda and I finally arrived at Merimbula, a seaside village with tidal lakes and a causeway. A rambling bacon factory was the only sign of commercial enterprise except for the stores, a garage, and a few normal country-village activities. We were told of a man, up the hill to the north, who had log cabins for hire which would fulfill our holiday needs and our desire for adventure into loneliness simultaneously.

Merimbula in the 1930s

Merimbula in the 1930s

From the open door of our cabin we watched the Pacific Ocean for a week as it rolled in from the east and crashed onto a strip of golden sand fifty yards wide; The small narrow beach separated it from the black flatwaters of a lake which extended back into the hinterland until it lost itself amid the primaeval bush every Australian claims as his own. The inherent quality it had - a sense of never having been occupied by man - made it the destination of every pioneer; it somehow justified enduring a primitive existence which celebrated the renunciation of many social amenities - one could be alone, with the Creator. This spirit was the lynch pin in our national existence; all men and women had an equal chance to succeed.

Returning home made us aware that the peace we had taken as our birthright could be lost forever, but this did not fill us with too much anxiety because we had so little to compare it with. The global conflict gained in intensity as the Daylight Battle gave way to the Night Battle for the beleaguered British, who were nationally at their magnificent best. Whatever Australians may have felt about them during peacetime dissolved into an admiration which could not be expressed rationally. Their courage was neither physical nor mental, nor even what is called spiritual. It was the concrete evidence before our eyes that as the mills of God grind both slow and exceedingly small, they produce the knowledge that man, fallen though he is, is still made in the image of God. The nightly horror of London Coventry and all the rest could not destroy the undestroyable. It all had a strange effect on me. I hated the English for their society of double standards and exclusive opportunities and for their bad sportsmanship over bodyline cricket, but they were like ourselves now - man for man facing the bodyline bombs, and not even ducking as they saw them coming.

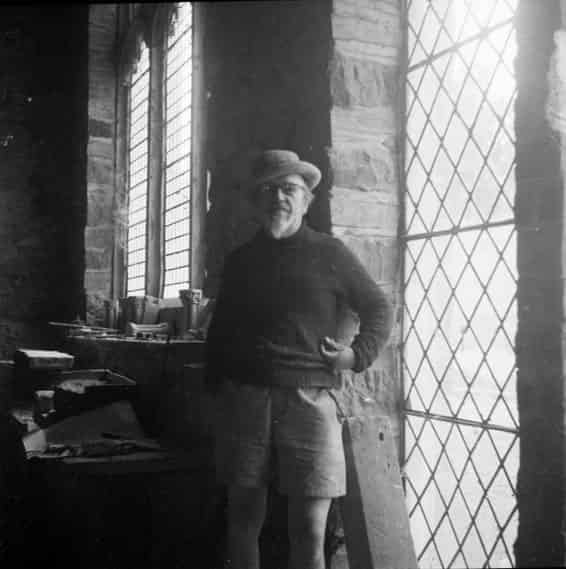

Frederick Romberg in 1936

Frederick Romberg in 1936

Our hill on the eastern side of Heidelberg overlooking the Yarra Valley comprised an interesting group. Bob Eggleston, the young architect, had joined the air force; but Frederick Romberg, a German architect who had fled his homeland two years before, was practising his profession with a freshness and ability that was something new to us. Frederick built two interesting houses on land which Mernda and I had first sought but could not afford. Fortunately, he had financial backing from Verina (his wife, who was Swiss) and her family to produce proper architectural buildings. He managed to complete his first major project, called Newburn, in Queens Road, Albert Park, before hostilities closed down all such opportunities - a feat for which I admired him greatly. We were the same age, but he had done so much where I had done so little. He had a comprehensive mind which had partly been developed by the study of law. He thought constructively, as a leader who knew where he was and how to go about getting things done, while I was still taxing the good will of my bank employers.

Mernda, Frederick, Verina, and I became close friends because of the circumstances the war caused. Both couples produced families at a similar rate, and we had many interests in common. We had heard about Montsalvat - the Eltham colony of artists which lived six miles further up the Yarra Valley - and all of us desired to see it for ourselves. Montsalvat had gained an unenviable reputation among middle-class suburbia - it was a place of free love - which gave a fillip to my imagination. I had no desire to depart from my monogamous relationship with Mernda, but the Montsalvat people appeared to enjoy a freedom in our circumscribed world which made them sound worth getting to know. One Saturday Frederick, Mernda, and I set off for this Promised Land which lay in the hills and valleys and followed the course of the river to the middle ground of the overall landscape-painters' view. The magical shades - pink, blue, and brown - merged into one over-all colour, beckoning us. It spoke of an Alhambra Palace or a Xanadu Cavern hidden in the bowels of a primaeval eternity. It was the source of imaginative possibilities, and it kept us sane in the dark year of 1940.

With every passing year, it becomes increasingly difficult to realise how enormously Australians' attitudes have changed - from pioneering, to pontificating. In less than half a century, the land and its people have exchanged a sense of wonder for the brash world of the Yahoo.

Frederick, Mernda, and I set out for Montsalvat late in the year, in search of the artists' and nudists' haunts we had heard so much about. Our journey lay through the Banyule landscape redolent with the ancient redgum savannah which stretched out into the anticipating beyond. From every tree, ubiquitous magpies carolled the unimaginable songs of the antipodean eternity. Our path lay over the hills and descended into the valleys of the Lower Plenty. The track up towards Montsalvat was challenging, but its path was equally beckoning and mysterious. Eventually we stood, rather exhausted, at the main gateway on Metery Road which led to the Artists' Colony. Montsalvat has never quite been open to the public: entrance has always been by invitation and desire rather than by chance.

The Great Hall at Montsalvat

The Great Hall at Montsalvat

There are some experiences in life which fall outside the normal structure of social intrigue and mystery. We immediately realised it was one thing to stand within the grounds of the Artists' Colony and observe its European buildings, and quite another to understand how they had gotten there and what they all meant. They were impressive, very different from any construction I had ever seen. As we approached the entrance of the Great Hall - a massive masonry edifice at least forty feet high crowned with a well-proportioned slate roof, clerestory windows, parapets, great hand-carved medieval stone windows, and cantilevered balconies - that went back centuries. The yellow stone walls were still clean and naked and not yet glazed, but there was an undeniable sense of comprehension of intent and of timelessness of execution. The only thing missing was man, but we felt that perhaps there was a hunchbacked figure in ancient clothes lurking in a shadowy corner and watching us. We had to push aside two or three eucalypt saplings which had regenerated themselves close to the main entrance. As we looked inside, up forty feet into the belfry, we experienced that sense of awe one has at first sight of a great natural wonder. The three of us spent some minutes examining this sight in silence until Frederick tried to guess at its enormous cost if it were new; no, it had to be the ruins of a vanished civilisation. At this moment our reverie was disturbed by Mervyn Skipper - Jorgensen's Amanuensis - who appeared from nowhere and made himself known to us. His sharp hawklike nose, rather tuneless voice, and shock of straight hair cast him in the role of a recorder, not an originator. He told us the Colony was the inspiration of Justus Jorgensen, and never of himself. It was Justus, or 'Jorgie', whom we had hoped to see, and we were not to be disappointed. Jorgensen was of Norwegian descent, and there was more than a hint of the Viking about him. His father and his father's brother had travelled from Norway to the Great Southland in a unique way. They had designed an unsinkable lifeboat, filled it with supplies, studied the prevailing winds and tides, and set forth to get there by using the natural forces surrounding them instead of by fighting them. Their argument was that most people who found themselves at large on the ocean in an open boat died from exposure and exhaustion, a fate they had no intention of suffering. It was even possible for the craft to capsize and right itself again without a great deal of danger. Jorgie's father was a sea captain by profession, and he eventually arrived at Geraldton in Western Australia, where he became the harbour pilot. When I knew him better, Jorgie told me that as a boy he had spent much of his spare time on the wind-jammers which lay at anchor in the port waiting to load grain for Northern-Hemisphere destinations.

Our first meeting took place in the Montsalvat dining room, one of the earliest buildings erected on the site. It consisted of pise walls with pairs of narrow french windows along one side, overlooking the valley which had remained unchanged since Walter Withers, the premier Impressionist painter, had walked around it early in the century. The colony which Jorgensen had named Montsalvat had taken possession of some twenty acres early in the Depression and had started to build a retreat isolated from the frustration of the world by carving out an adventurous life in the midst of the general despair surrounding them in Melbourne. We sat down on forms which ran along both sides of three heavy tables of medieval design. Tea was provided from the adjacent kitchen, and just as Mervyn set about explaining it all, the master appeared through a low stone doorway which was half-concealed at an inner corner of the room. He immediately took over the discussion, which Frederick had been conducting, with professional skill.

Justus Jorgensen

Justus JorgensenJorgie wore glasses which made it impossible to look into his eyes. The images of his followers, who were seated across the table, appeared to be reflected on the lenses through an odd quirk of the afternoon's light. When he spoke of 'my pupils', a slight slur in his voice turned it into 'my peoples', a title we could see was well understood, and with which his students concurred. It was the first community I had ever visited which seemed prepared to accept a common lifestyle and common ownership of possessions. In a day when few men wore beards, Jorgenson's Christ like appearance gave him the air of a Biblical prophet; he took advantage of this, emphasising various points of his arguments with the hypnotic movement of his pudgy hands. His conversation was heavily impregnated with references to Socrates and other Greek figures, on whom he seemed to have modelled himself. His account of the Colony he ruled over was, in general, an attractive explanation of how much better it had been to live adventurously in his little world which pursued art, beauty, and uninhibited living, than in the great world outside frustrated by disaster, poverty, and unattainable objectives. His greatest appeal was to the artistically and romantically inclined who, though they did not constitute the forefront of the creative world, all had talents he could develop and make part of his grand plan. He used to refer to himself as the conductor of an orchestra and to his pupils as the players. He neglected to mention that he also composed the music and collected the takings, which he spent on materials to further his great dream. He and his wife Dr Lily Jorgenson had spent some years in France before he bought the land in Eltham on the eastern side of the Diamond Creek Valley. The Jorgensons had been members of Meldrum's Tonal Painters School until the group fell out with one another and Jorgensen set up his own group. He had a Melbourne studio which became a centre for philosophers, rationalist writers, and the painters. In 1934 they all decided to live full-time in the beautiful rural valley full of mists and little cottages with corrugated-iron roofs and orange-coloured chimneys. Hawthorn and cherry-plum hedgerows which had survived since the area was first settled some eighty years earlier formed an English-countryside pattern along the river flats. The district's greatest charm lay in the fact that development had bypassed it when a new route to the mountains had been developed further to the east. Its early-valley-hedgerow pattern mingled with the yellow box, redbox, and manna gum stands which remained, with the undulating unmade roadways dividing up the small orchards of fruit trees and cow paddocks. It was gentle, unambitious land perfectly suited to the artists' desire to withdraw from the general world so that they could continue in peace to espouse the belief that bush and beauty were similar to Shelley's conception of Truth and Beauty being one.

The impression I gained of the enclave on my first visit has changed surprisingly little over the years. I found its inhabitants interesting and intelligent, and their conception of spiritual matters diametrically opposed to those I had inherited from my family. Justus Jorgensen was their deity, no matter how they demurred. I only visited once or twice between 1940 and the conclusion of the war in 1945, prevented from doing so by the pressures of daily life, a young family, and having to earn a living at the bank each day.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >