A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Author: Alistair Knox

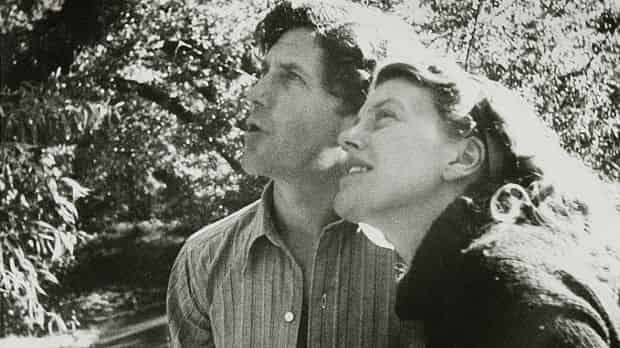

There were one or two places where artists and art potters - art pottery was still in its infancy - would always meet, notably the Primrose Pottery in Little Collins Street. When I first visited there in 1932 it was run by Cynthia Reed, John Reed's sister, who was later to marry the famous painter Sidney Nolan. Sam introduced me to this scene because he was just starting to design modern furniture. I found Cynthia vivacious and attractive, she made me wish I were ten years older. The George Bell Painting School was then in vogue, and men as diverse as Arnold Shore and Russell Drysdale were moving away from the traditional scene, though they still constituted but a minority group when compared with the traditionalists.

Cynthia Reed, 1945

Cynthia Reed, 1945National Gallery of Australia.

Sam and his girlfriend Moya Dyring had a studio at 92A Little Collins Street above Walshie's, the tailor's shop, which had once had a tiny residence on the first floor consisting of three rooms. Walshie the tailor was small and grey and a chain-smoker with a tubercular cough which made me shudder as I passed by him. His habit of spitting into the fire grate must have made his shop one of the unhealthiest spots in the whole metropolis. But we ignored this unwanted gratuity from our landlord with grace because the three rooms were only costing us 12/6d. weekly - a figure which would have been higher had the residence been in better condition. Our only worry the weekly rent, small though it was. The studio was the melting pot of our ideas and occasional parties, and as the decade progressed it evolved into a real centre. Among our visitors was H. V. Evatt, who was to become attorney general in the postwar Labour Government and, later, Opposition leader in the Australian Parliament. His wife, a distinguished art connoisseur, bought occasional paintings from Sam; they could vary anywhere from French Impressionist to abstract, without difficulty. One which still remains is a piece Sam and I titled Organised Line to Yellow; we named it as we looked at it, right after he had finished it. Another painting - somewhat cubist in spirit, and painted the next day - was named Modern Man. It remained in the John and Sunday Reed Collection for many years, but it now seems to have vanished altogether. I never thought the canvas or the paint would last for more than twenty-five years. I sometimes wonder whether it might not lying in some forgotten corner - a mass of flaky chips of colour and a disintegrating piece of hessian-like material that had acted as a canvas, split and falling off its stretcher.

The very worst of the Depression began to recede around 1932, and there was hopeful talk among us about going overseas. I could rarely stop thinking about this impossible dream: the ocean liners still came and went from Port Melbourne every second day, and they always appeared to be full.

Margaret Lord, Powerhouse Museum

Margaret Lord, Powerhouse MuseumThe student's best chance of going abroad was to win the travelling scholarship offered by the National Gallery; it was annually awarded to whichever final-year student produced the painting which the independent judges considered to be the best. Sam was due to compete in the upcoming contest; since he had been an outstanding student for years and there was every chance he would win it, I was making plans to go with him - come what may. My girlfriend,Margaret Lord, whom I'd known since I started attending the Gallery, was an art teacher at the Williamstown High School and had similar intentions to go overseas; after all, we reasoned, some of the commercial artists had taken the plunge without starving to death. Margaret was a beautiful country girl six years my senior, and we mutually understood that her previous boyfriend would one day return from his bank job in Western Australia to claim her. He was taking a along time about it and Margaret - who was always known as 'Peg' - and I became constant companions in the meantime. The accomplished John Vickery was also about to marry and seek further advancement in the United States.

There were five competitors for the travelling scholarship, and the entries were painted over a six-month period. The artists comprised four females, and Sam Atyeo. The women were all under the influence of the director, and Sam believed they had joined together in a vendetta to beat him no matter which of them won. Realising he stood little chance of winning , Sam decided to commit the unpardonable crime - to paint a modern painting. Each contestant had a private studio, and none knew what the others were doing. The paintings - to be judged by three men of national standing led by Sir John Longstaff - were finally hung the day before the contest. I slipped out to buy an early edition of the Herald on that fateful day, only to discover Sam's photograph on the front page with the headline 'Artist Claims He Is Slighted' - no less than the truth. The small print explained the competition; it then reported that Sam's entry had not been hung with the others and that no reason had been given for its exclusion. As soon as we could all leave work, a large crowd of us gathered at the studio to find out the reason for this outrage. Everyone was well aware of the open hostility between the director and Sam and of their diametrically opposed opinions about 'modern art', but we still were unable to comprehend the situation, absent some extreme justification. The underlying facts were that Sam, knowing his prospects for the scholarship were hopeless, had decided to blow the situation wide open. The competition rules stated that the entries must contain figures of two nudes and one half-nude. The two nudes in Sam's composition were still realistic enough - they bore an unmistakable likeness to two of the female competitors - and the half-nude was the redoubtable director himself. The painting was titled Lot Admonishing His Daughters; this referred to the biblical account of the daughters of Lot bearing children of their father's seed - which occurred after they wined and dined him after they fled the corrupt cities of the Plains, before God destroyed them with fire and brimstone. The painting was of average quality and too far-out to be merely representational; but its meaning was perfectly clear. The sight of it was too much for the director, so he exercised his authority: he did not permit the judges to view it, calling it an insult to their finer feelings.

Reed/Heide Photograph Collection, State Library of Victoria.

Reed/Heide Photograph Collection, State Library of Victoria.Sam had discovered all of this that very morning; he immediately phoned the Herald office, which sent two men and a truck to assist him in bringing the painting down to be photographed. The three marched up the Melbourne Library steps only to be told to that the painting had been relegated to an office where it was under the guard of an attendant. Sam knew the attendant quite well, so he approached him and told him he had come for his painting. When the attendant told him Mr Hall had said he as not to let anyone in, Sam asked him to inform the director of the situation. Immediately the attendant left Sam and the drivers; they quickly grabbed the painting and walked out the front door, down the steps, and into the waiting truck. The canvas was large and had to be held on-edge: this made it plain for all to see. What the painting's journey down Swanston Street did to the pavement watchers in those conservative times is not recorded, but Sam said that the Herald man who stood with him in the open-bay van remarked casually as he glanced at the work, 'It is pretty ordinary, isn't it?' and Sam agreed with him that it was - in an equally casual manner. The painting did not make the Herald, however, because the newspaper still retained a policy prohibiting it to print images of naked female figures - whether they be photographed live, or painted on canvas.

Back at the Studio we decided that to phone the Herald to ask whether they knew of Sam's whereabouts. They replied that they were equally anxious to locate the 'slighted painter' and that we should notify them immediately when we found him. A few minutes later, Sam and I entered the Herald office and casually announced that we wanted to leave an address in case anyone rang for us. We were politely asked to wait for a moment to see the reporter - who was still talking to Sir John Longstaff, the chairman of judges - which we did with some trepidation, especially as neither of us had any real idea how the all-powerful press would react.

Sir John Longstaff. Self portrait

Sir John Longstaff. Self portrait

The reporter, smelling of cigarette smoke and urgent business, eventually burst in on us. His short figure was clad in a conservative blue suit, and he sported a bowler hat - which was a little circumspect even in the Depression, when anything could happen. We thought the hat might be in deference to Sir John, who was a doyen of the art world, and we wondered what he must have said to the Herald. The reporter started to abuse us for criticising Sir John, who had just been at pains to make it clear that the judges had had nothing to do with the painting's removal - they had not even seen it. In a few moments, we cleared him of any implication in the plot and put full responsibility back on the director. Sam's revenge for his imagined injustices had been swift and sure: the following day's newspapers gave the matter considerable coverage - with Sam's complaints and explanations on top, and the judges' answers in smaller headlines underneath. At a time when matters other than gloom and poverty were seldom reported, the cause of modern art - especially concerning nude paintings - took off like a rocket. Sam's painting was exhibited in a Collins Street antique shop and visited by an unending queue of people for a whole month. Not one in a hundred saw anything in it other than some apparently deformed figures; it still haunts some viewers, though, and has probably never quite disappeared. But that mattered little: the cause had been capably launched by its first Australian protagonist.

The Meldrumites and the Tonal School might fret and cry 'Foul play!' and the Realists fume and mutter 'Sacrilege', but it was too late to mean anything. Gertrude Stein - the Modern movement's current mouthpiece's - poem 'A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose' was here to live on and be recited in the most fashionable salons.

Soon thereafter, Sam put on an exhibition of variable quality. He sold some paintings, and the publicity continued unabated. But publicity did not always guarantee financial stability: Sam realised that his proposed European journey would need to be financed in some other unusual manner.

The following year saw Sam set out in earnest to achieve his goal. He spent considerable time at the Primrose Pottery Shop designing modern furniture. The owners - Fred Ward and his wife - had been employed in this activity for some years in their own house in Glennard Drive, Eaglemont. They had produced some economical well-designed and executed pieces that were the true genesis of the modern-furniture era in Australia. Sam quickly absorbed their principle of using natural timber and good shapes, at the same time adding his own touches. Australian timbers were not generally as appreciated as they should have been, and both Fred and Sam set about changing this misconception. Most of Sam's pieces were functional first and feeling second. His favourite combinations were of mountain-ash structures set on jarrah bases. The timber was always thick and solid and wax-finished. Joints were visible where possible. However, he would sometimes branch out into quite original designs. By this time I had been transferred to the Service Department in Head Office, probably on account of my clerical inabilities; but it suited me, because the office was just around the corner from the Primrose Pottery Shop. I often slipped 'round at lunchtime to discuss with Sam our going-away schemes, which were still always financially elusive. Sam was now well-ensconced with John and Sunday Reed, who were gaining prominence in the awakening Contemporary Art School and who had purchased a large timber house on ten acres in Templestowe, just over the Banksia Street Bridge which connected it to Heidelberg. The Reeds and Sam were on their way to Warrandyte to visit the sculptor Danila Vassilief one Saturday afternoon when they saw the house about to be auctioned. Sam urged John, who was financially very well endowed, to buy it - which he did, for £1,000. The house, which was charming but old , stood in its ten acres of the Heidelberg Impressionist School landscape; it was rebuilt later, in the early 1950s, in Mount Gambier stone. It has now become a regional gallery called 'Heide' and became the inner sanctum of the Modern Art movement for over thirty-five years. It was here, shortly after World War II, that Syd Nolan painted his first Ned Kelly series and from where he was later to marry Cynthia Reed and leave for Europe.

John and Sunday Reed

John and Sunday Reed

In 1934 the Heide would stand in rural isolation as the full white moon rose over the Yarra Valley just as the sun was setting. The mystical, reflected light that so moved the Australian Impressionist painters would turn red and purple in the eastern sky as the magpies sang their final carol for the day and a melancholy mist settled over the river. I vividly remember Sam's vitriolic remarks from around this time; they centered on a particular painter, whom we had never seen before, turning up at the Primrose Pottery dressed in tattered clothes and wearing old sandshoes. He proved to be the famous Ian Fairweather, from the north of Queensland. His paintings, which were done on rolls of paper, were better than Sam's, who immediately saw the works as a serious threat to the position and standing he was building up for himself. When I arrived at the shop, Sam was alone. Ian Fairweather's paintings had been seen by some female painters of independent means, who believed they had discovered a genius and had taken him out for a meal. When the women asked him how much money he wanted for his work, he just looked up and told them that all he wanted was food. Sam had been left in charge of the Primrose that afternoon, and I was his first opportunity to set matters right. He told me what had occurred and then shouted, 'He's a charlatan! - a charlatan, I tell you! - and this is how I know: he was wearing dirty old sandshoes, and they were torn and the tear was brand-new! I tell you, they were new shoes dirtied up!' I never learned the entire story, but the threatened crisis resolved itself: Ian Fairweather quietly left the scene without making any effort to usurp anyone's position.

Edward Dayason, businessman

Edward Dayason, businessman

Sam's attention was again diverted when he got wind of an opportunity to make enough money to get him to Europe - assistant in the development of a city building in an advisory aesthetic capacity. Edward Dyason, a highly successful and intelligent stockbroker, owned an old bluestone building in Chancery Lane between Collins Street and Flinders Lane at the rear of St Paul's Cathedral. The building in its existing state had been condemned, and its age precluded altering the existing walls to allow for greater areas of fenestration - essential if the building if were to be retained. The other alternative was to demolish it and start again; this would be about six times as expensive. A group of six architects was lobbying vigorously for the latter alternative - a situation not unheard of in professional circumstances, especially in such straitened times. I don't know who tipped Sam off about the possibility of his being approached for an opinion, but it no doubt was one of his new rich friends who had 'discovered' him after the Modern movement began. With earthy sanity, he called on an old stonemason, a man who hailed from Coburg and the basalt-quarry area; Sam asked him whether anything could be done to retain the old building's walls and update them. The mason came into town and tapped here and there around the structure with his mash hammer, and then declared himself: 'These walls are quite sound, Sam, and can, with the addition of a three-inch cement render, be accepted as new masonry walls'. The very next day Sam and Edward Dyason walked past the building together; Dyason suddenly asked Sam what he would do to update it. In the presence of six qualified architects who said the structure must come down, Sam's response was dramatically simple: he opened his pocketknife, walked over to the wall, and started to screw the blade into the mortar in the wall. With an air of confidence, he declared that the building was stable; that it could be rendered with three-inch cement that would cause it to be accepted as a new wall; and that in that event, there could be sixty-six percent glass on the facades instead of the present thirty percent. Dyason asked him whether he would like to take on the aesthetic control of the alteration. Sam seized the chance. Within six months, it would provide him with the money to set up in France.

Sam was introduced to the architectural conclave for a conference to explain his proposals. He was told by the opposition in explicit terms that his plan to double the window size was just not on. It was then agreed to interview the city engineer in the Town Hall just across the road. Sam used to keep us in fits about these proposals as he related them to us in the Studio later in the day. All the architects wore bowler hats and blue suits, while Sam attended meetings in the modern painter's rag (??) of the day, a sartorial innovation that he and I had introduced three years earlier, namely, ginger-coloured Harris Tweed jackets and slacks and enormous Zug tan leather shoes - all of which presented a strange affinity with his auburn hair and freckled face. Sam's original proposal had been tendered sketched in pencil on the back of an envelope , but when it was handed to the engineer the latter gave no outward tremor of horror or humour. Instead, he got out his rule and went over the report carefully. After a suitable pause, he declared it was approximately correct. It was back to the office, to arrange for preliminary drawings to be provided by the architects and subject to the approval of Sam Atyeo, Artist. The frustrated professionals, looking on as this radical interloper interfered with their fees - Sam was reducing costs - worked up a hatred for him as he revelled in his authority over this group of bowler-hatted and brief-cased bureaucrats. At each meeting they posed trick questions to bring him down, but Sam had done some architectural studies years earlier and was always able to give more than he got. Edward Dyason appeared to enjoy these proceedings, and he saw to it that Sam's advice, which was both cheap and good, was obeyed. The building in Chancery Lane was for many years the home of Tim the Toyman, and one of the very first modern buildings in Melbourne. It has never dated. It still stands today, justifying its aesthetic designer. Even as the project reached its final stages, the frustrated anger towards Sam continued unabated. By this time he had become so sure of himself that he ventured into philosophical reasons for his decisions. This nearly made people berserk: he was teaching them their own business. At the final conference, he found himself holding forth about using white toilet seats, despite the fact that toilet seats had always been black. He deplored this lack of imagination, saying that black was dull and dirty. The opposition rose and said that white seats were not available. Sam said they were. 'Where?' they demanded. Grasping at the first name he could think of he replied, 'Brooks Robinson's'. They decided to test Sam's assertion then and there. Sam and the six bowler hats set out immediately for the Brooks Robinson's Elizabeth Street showroom. There the shop-walker ascertained the elegant group's wishes within two seconds: 'Lavatory seats', said Sam. Upon being shown to the second floor, Sam approached the salesman: 'Do you have white toilet seats in stock?' he asked. 'Yes, sir, we have. They arrived from overseas just a week ago'. Sam tried not to let his anxiety show, and to look as though he'd known all the time.

Sam's commission fee, augmented by the proceeds from a modern pianoforte recital in his honour, soon had him safely at sea, bound for Paris - and me left lamenting on the wharf. Nineteen thirty-four was the year of Melbourne's centenary. A brave show was made here and there, but no one felt there was much to rejoice over. Sam's departure had left the Gallery School bereft for me. I could no longer walk past the stuffed body of Phar Lap at the outer entrance to the school with any sense of joy, and the musty smell of the aboriginal artifacts also failed to stir me. There was a new sense of urgency, however, in the great world out there. While Britain and France dithered, Germany had marched into the Rhineland unopposed. The Edward VIII controversy was brewing even as George V lingered on, and Queen Mary's erect figure seemed to be suspended between the unchangeable past and the dubious future. It was clear that nothing would remain as it was.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >