Design and Building Career

Biography

1912-1929Childhood

The Bank

1930-1939

Adolesence

Marriage

1940-1949

The Navy

First Buildings

Bohemian Associations

1950-1959

Early Houses

Margot

Professional Building

1960-1969

Hard Times

Knox House

Landscape Architecture

1970-1979

Helping Hand

Eltham Shire Council

Mature Houses

1980-1986

Postscript

Introduction

Alistair Knox was a designer, builder and advocate for an alternate lifestyle. Between 1946 and 1986 he designed over 1,000 houses, a number of churches, schools and other buildings. The job numbers reached 1266 of these he built about 350. He is best known for his mud brick output of about 300 buildings. These were built in two periods: before 1955 and after 1964 but mostly post 1970.

The thing which stamps Alistair out from his contemporaries, apart from his amazing output, is that he was a builder. This first hand knowledge informed his designs. His mature work could be built inexpensively by people with limited skills using reclaimed materials. A democratisation of the building and design process.

In the Beginning

After being discharged from the Navy in 1946 Alistair Knox started a Rehabilitation Course in building construction at the Melbourne Technical College (now RMIT University). At the time he was a teller in the State Savings Bank of Victoria. He had joined the Bank on leaving school at 15, shortly before the Great 1929 Depression. In his unpublished autobiography, Alistair describes his time at RMIT and the beginnings of his new career in his unfinished and unpublished autobiography A Middle Class Man.

He said "the reason I was choosing building and design as a vocation was that I was naturally drawn to it as an art, a philosophy, and a science. The sets of chisels, saws, and hammers with their beautifully polished handles that I had learned to use in Uncle Jim's workroom as a child - these made the mechanics of construction appear very simple. I saw it merely as a matter of putting one thing on top of another. Design methods were related to the comprehensive principles I had learned from my father and the instinctive practical skills I had inherited from my mother."

He continues this description in the next chapter and later tells how the Knox building enterprise began.

Alistair saw that "There was a whole new demand for building as Australia saw its vision of prosperity extending endlessly into the future. The deferred pay the servicemen received on demobilisation, along with the pent-up repressions of the past difficult fifteen years, provided opportunities that had never been seen before. The only problem lay in the lack of materials."

The Bryning House, 1946, showing Matcham Skipper's chimney and John Yule's stone wall Photo: Australian Home Beautiful.

The Bryning House, 1946, showing Matcham Skipper's chimney and John Yule's stone wall Photo: Australian Home Beautiful.

Alistair describes the trials and tribulations of building his first house as he battled with inexperienced builders and shortage of materials: a voyage of discovery.

The First Mud Brick Period 1947-1953

The third house was in mud brick. As, apart from the offerings of Whelan the Wrecker, there were no other building materials available it was an essential step. It was also assumed to be cheap.

Alistair describes the beginning of the mud brick era in his book 'We Are What We Stand On' They were carefree days after World War II when the world was coming to terms with a new order. No one really knew what they were doing except for the forelady, Sonia Skipper (Matcham's sister), who'd built in mud brick at Justus Jorgenson's Eltham artist colony, Montsalvat. And, Alistair was absent, working at the bank. The link above takes you to his descriptions of these early days.

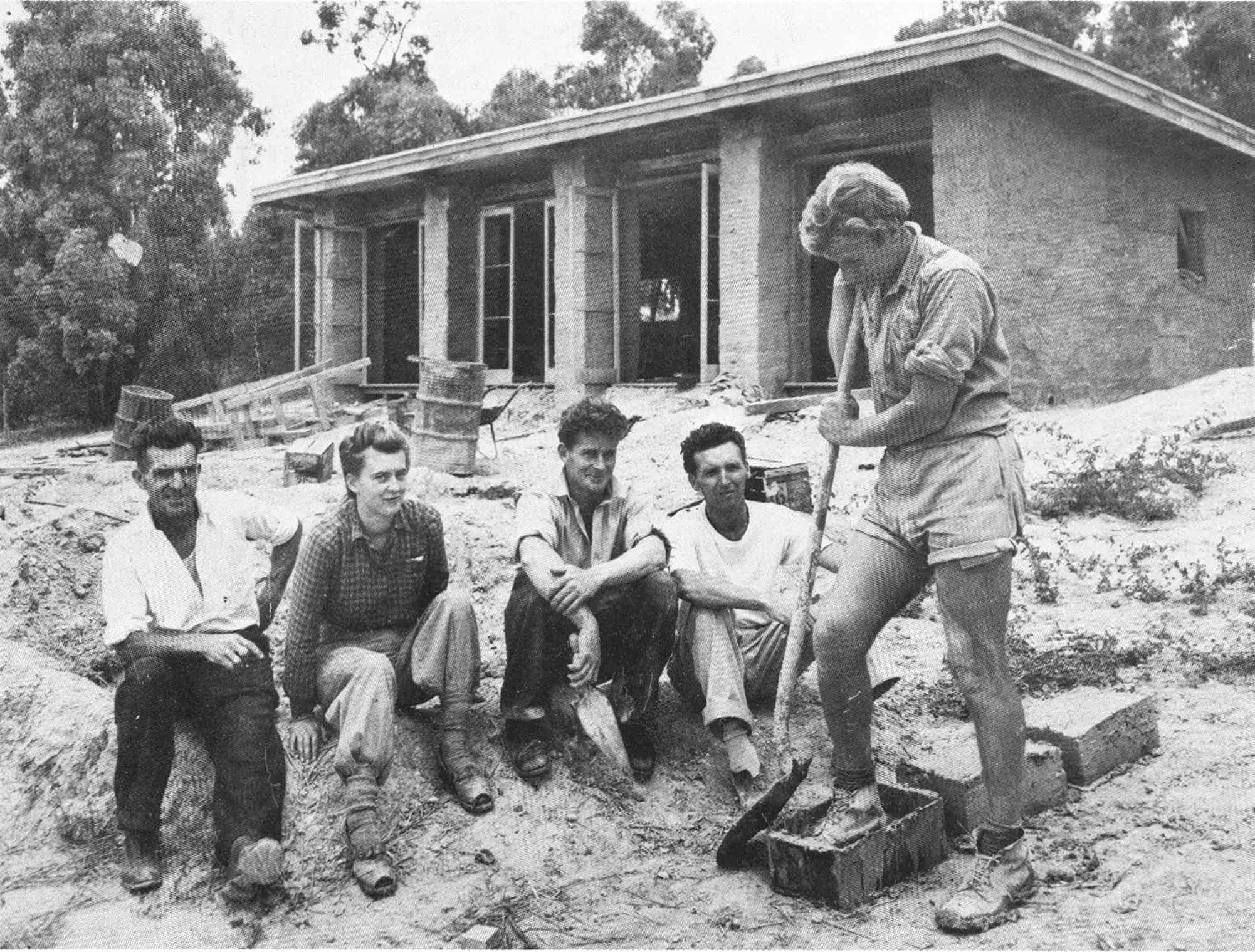

Left to Right: Laurie Mayfield (carpenter), Sonia Skipper, Alistair Knox, Tony Jackson and Gordon Ford with the English house in the background

Left to Right: Laurie Mayfield (carpenter), Sonia Skipper, Alistair Knox, Tony Jackson and Gordon Ford with the English house in the background

A series of mud brick buildings followed: A studio for Professor Macmahon Ball, the Periwinkle, the modest first stage of the Downing/Le Gallienne complex and his first large house for Phill Busst. This activity attracted considerable attention in the press and gave him a headstart in design and building. During this period Alistair came across the man who would physically carry the fledgling building company to the next level, Horrie Judd

He says that "this was the real beginning of my major early earth-building period and close association with Horrie Judd, which continued for some years. We eventually parted company because of his inability to delegate work to his subordinates. He saw them merely as long-haired intellectuals - only to be entrusted with cleaning-up chores, while he set about doing their specified work in addition to his own. He considered Gordon Ford an exception because of his physical strength and Scottish endurance and stubbornness."

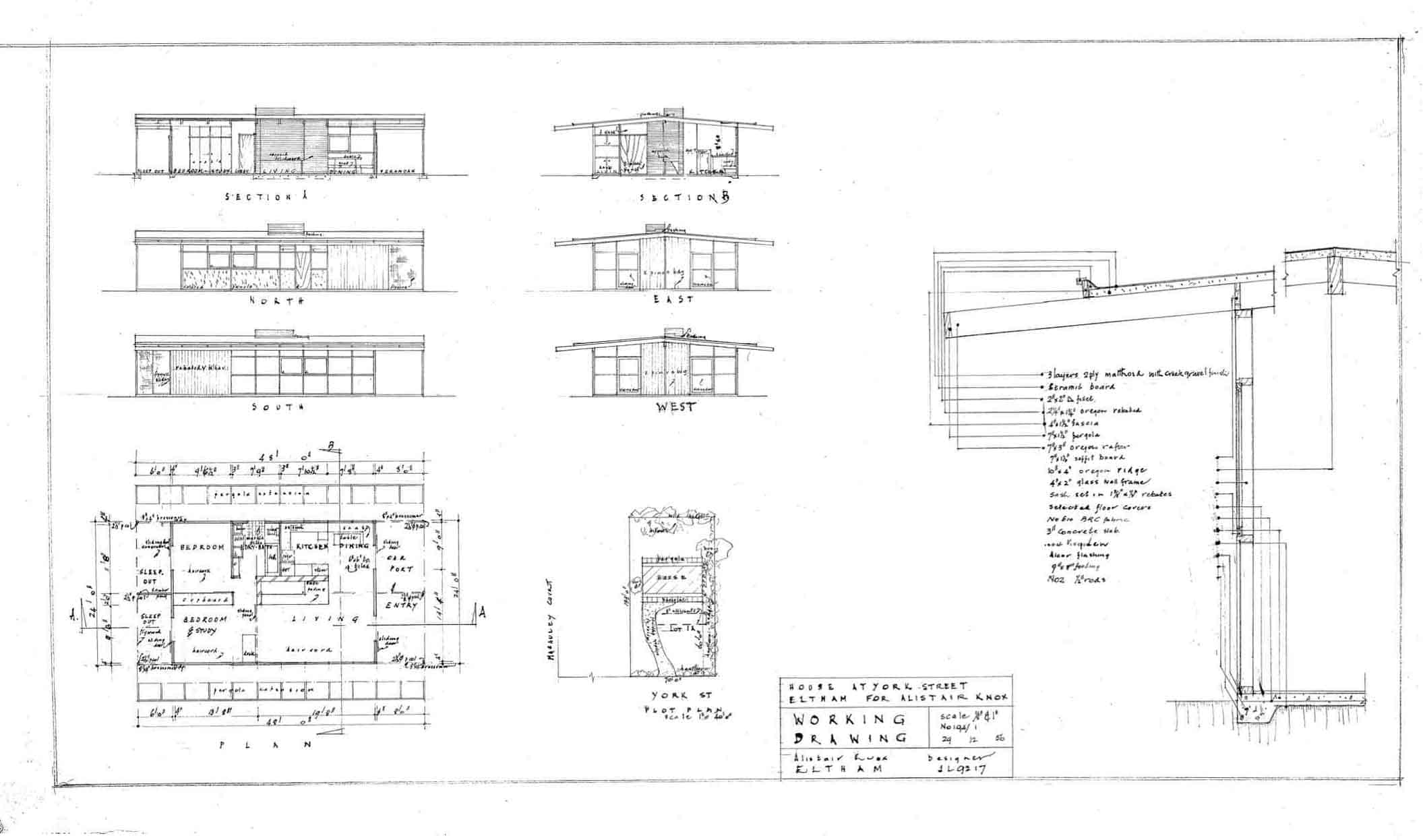

The Modular Houses 1955-1961

By the early 1950s the immediate post-war shortages of building materials had eased and by now Alistair was employing tradesmen not mates, labour costs increased but so did productivity. At the same time demand for housing was going up.

A joinery had been built at the rear of the Knox family three acre property in York St Eltham where all the framing and joinery was done. Wood machining tools are allergic to the rock-hard nail infested second-hand timber of the earlier mud brick days. It was also hated by the men. Good quality oregon was plentiful and reasonably priced. It had become cheaper and more efficient to use new material, so second-hand materials were left for others to reclaim.

The other innovation was Stramit. This was compressed straw in a cardboard covering. It came in sheets that were 4' wide and 2" thick", they could support themselves and the weight of a man. This material was laid in steel channels directly onto the oregon rafters and covered with malthoid, tar and creek gravel to form a finished roof. It was incredibly fast and efficient. This more than anything changed the houses. Stramit enforced a 4' module which was mirrored vertically - windows started 4' from the ground and were 4' square - doors were 4' wide and sliding. The houses took on a uniformity that was impossible with mud brick.

Prototype for the modular house, Knox house 25 York St, Eltham built in 1956 it was job number 194

Prototype for the modular house, Knox house 25 York St, Eltham built in 1956 it was job number 194

Alistair says that "as our design and building business increased and supplies of normal materials became available, it was a relief to turn back to traditional men and bricks and mortar. It was now possible to calculate results rather than be entangled in the unpredictability of eccentric mates and the vagaries of inclement weather, which were always the major complexity of alternative building."

And, in an unpublished article, 'Australian Regional Building' "It became increasingly clear to me that any worthwhile contribution to the Australian domestic-building scene had to be applicable to a two- or three-man team because the great preponderance of building was done by such groups. The Bienvenu 'Welcome' saw bench became a basis on which I planned the first truly modular buildings in Melbourne and, as far as I can ascertain, in Australia.

"The building plan was to get a roof on a house as quickly as possible. It should still be the same aim. ... With intelligent organisation we did this regularly in four days from the time we started the carpentry and to lock-up stage in 11. The excavating and slab work had been done in the meantime. With planning that would easily be provided, it was possible to start the slab and wall construction simultaneously, and complete them at the same time. The walls were made up in our joinery and delivered and fixed immediately with special nails onto the concrete slab. The roof members were all heavy-dressed oregon which were delivered straight from the merchant fully prepared for use."

This was a productive period for the Knox building enterprise with about 40 houses a year being produced including 47 on the Hillcrest Estate based around Lisbeth Ave, Donvale, most of which were still standing in 2018. This increase in activity required extra hands in the planning department. One, Geoffrey Trewenack, was a young architect who later went into partnership with the eminent Australian architect, Kevin Borland, another was Peter Glass who moved from building to drafting and became the office manager and Alistair's right hand man for many years.

Back to the Beginning: The Second Mud Brick Period 1964-1972

This started to change in 1960 and 1961 as the credit squeeze brought the Knox building empire to a shuddering halt. In 1959 there were plans for 24 buildings, 16 in 1960 and just 3 in 1961. This forced the sale of the York St houses and land. This cleared the debt but left him and his growing family without a house or money. Somehow he managed to acquire land in Mount Pleasant Rd, Eltham on which he built.

This was a crucial turning point in Alistair Knox's design career as financial strictures forced him back to his early mud brick days.

The Knox house 2 King St. Eltham. 1964 Job number 376

The Knox house 2 King St. Eltham. 1964 Job number 376

He describes the building of the new house in Belief in Building, Back to the Beginning "High-school boys asked for work in December, at the end of the school year. I had them make mud bricks. I took Lionel, the foreman, who organised and encouraged them. ... Bit by bit, under Lionel, those boys put a roof on the first two wings. ... It was a bit like an anniversary of the early days of mud-brick building. The colourful figures were replaced by high-school boys and one or two architecture students. But Keith Joslyn came from time to time to break more earth for the bricks, and to shape the land. It was great to be back. The spirit we start with is the spirit we never lose. The bush land site was identical with the character of our Eltham building tips of 1948 to 1950."

And, in Living in the Environment, Crisis and correctives: "Lionel Anette, the foreman, was capable and good humoured for the boys to work along with. He made the window frames on site from some second-hand material reclaimed from a well known architect's house that was being demolished to make way for a 'dark, satanic' commercial building being constructed beside the Yarra River nearer the city. Some of the other joinery material came from old whisky vats. It was clear grained oregon of the highest quality. When it was put through the wood working machines, it gave off a deep smell of whisky that made the whole atmosphere exotic and heady."

At this time Alistair made Peter Hellemons his partner in charge of building leaving Alistair free to design. Gradually this revolutionised Alistair's financial position and his work practices.

It was then that a young architecture student, John Pizzey, started working for Alistair. He stayed for 15 years and become Alistair's right hand.

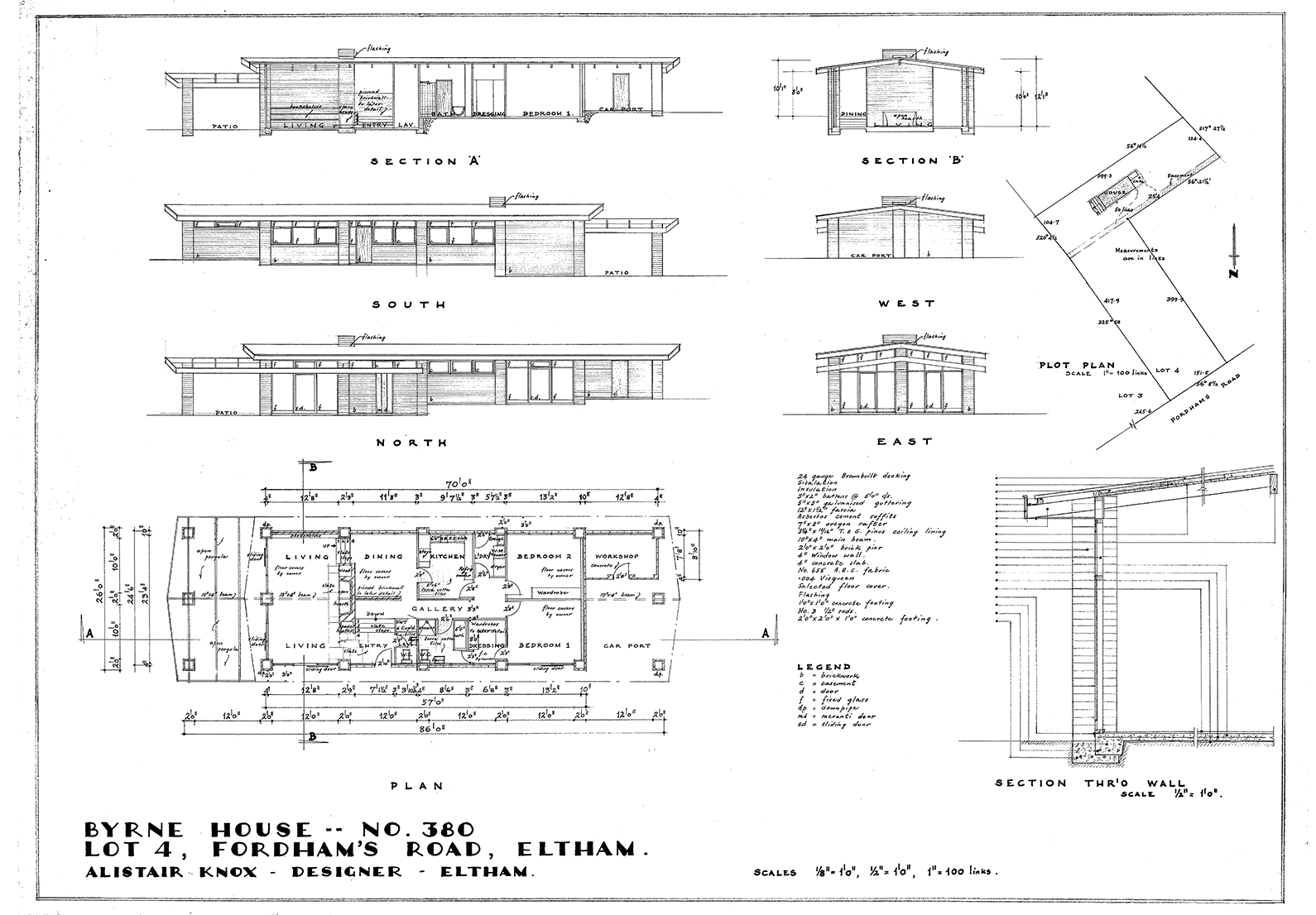

A typical 1960s house. The Byrne house, Eltham 1964 Job number 380.

A typical 1960s house. The Byrne house, Eltham 1964 Job number 380.

As the 1960s progressed the influence of the Knox house in Mount Pleasant Rd increased; more mud brick buildings were produced and the use of reclaimed materials became the norm. During this period Alistair's architectural vocabulary solidified. He moved to a 900mm module which resulted in windows and doors, which extended from floor to ceiling, providing a vertical element to his horizontal buildings. Clerestory lighting became universal. On sloping sites split-levels allowed the house follow the contours of the land. Important buildings from this period are the Barden house and the Pittard house

In 1966 Alistair, Peter Glass and Gordon Ford all became foundation members of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects. Alistair discusses this at length in A Middle Class Man. A number of garden plans follow this new found respectability. Peter Glass became more involved with landscape planning and eventually wound down his involvement with Alistair. His place was taken by John Pizzey who had by now graduated as an architect. John managed the office for Alistair until the late 1970s when he left to start his own practice, though he was still doing the drawing for Alistair until Bodhan Kysuk took over in 1984.

Mature Building 1973-1983

The Knox and Hellemons partnership ended and so did access to the joinery which Peter Hellemons had bought from Alistair in 1964. During this time the Knox building was done by a variety of builders with varying degrees of skills. These builders were sourced by Alistair and/or by the owner. This had happened to a certain extent through the Hellemons years but now it was universal. And, there had always been a number of owner builders.

As Mozart wrote arias that highlighted the strengths of the singer, so too did Alistair's designs flatter his builders. Thus, the Hellemons era plans were made using the skills of experienced tradesmen with normal materials. This, though profitable, could sometimes result in a certain degree of uniformity.

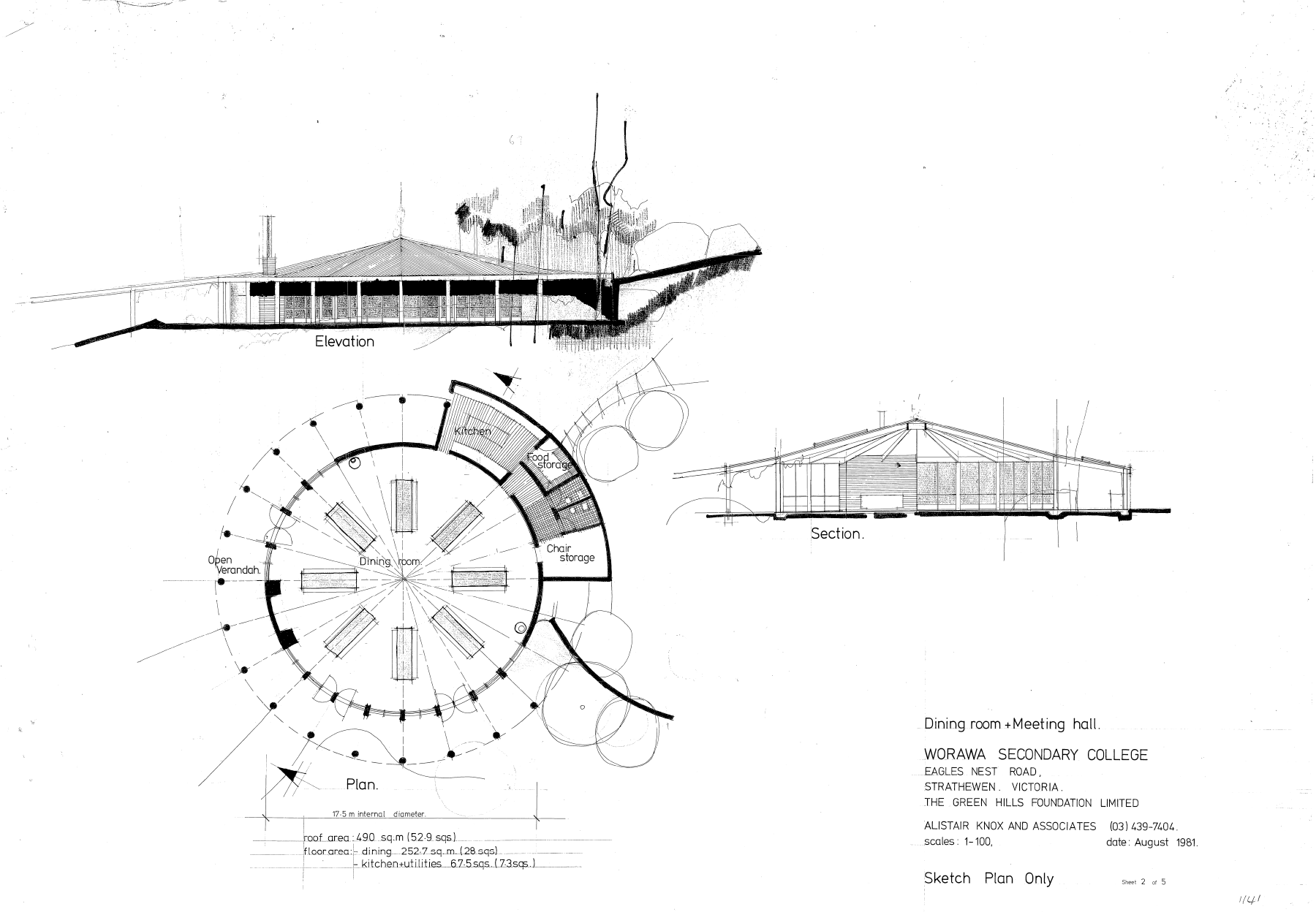

The Worawa dining and meeting hall. This was a projected aboriginal secondary college to be built by the students. Designed in 1981, job number 1181

The Worawa dining and meeting hall. This was a projected aboriginal secondary college to be built by the students. Designed in 1981, job number 1181

In this post 1970 era much more work was done on site and reclaimed material was an essential ingredient. In fact this material had a considerable effect on the character of the building. For example, this extract from 'Alternative Housing': "Jim Pittard was a Professor of Microbiology at Melbourne University and, by felicitous circumstance, some ancient ten by eighteen inch posts of King Billy pine became available as we looked for columns to build with. They had been underground for many years as a drain and were impregnated with dark, penetrating preservative that made them smell like tall, dark, mysterious beings from some remote quarter of Africa. ... He fell in love with its strange character as soon as he started to adze it. Several of these posts now stand in the middle line of the house and it is possible to walk all around them. By the time he had finished adzing, he saw them as living elements. I am sure that as he lay back in bed after a long day's work, the three words that occupied his mind were 'King Billy pine'."

Discussing owner builders, Alistair said of the Batty house: "I designed a building in a few minutes in my mind, but did not commit it to paper for several weeks as I weighed their ability to construct it. In order to make the alternative building program a success, it is essential to relate the character of the building with the capacities of the builders, as well as identifying the natural environment."

Freed from the uniformity of style required by professional builders Alistair's designing became more individual and was governed instead by the ability of the builder and the available materials. It was during this decade that Alistair's mud brick reputation rests. Almost all the houses in this period were adobe.

He says in his unfinished book, The Home Builder's Manual of Mud Brick Design and Construction "How could I press a button in Eltham and produce a true earth building in Anakie, 100 kilometres to the south-west? Normal contractors would destroy the feeling of the house before they got it a foot above ground level, even if the owners could have afforded in such a remote area the enormous costs of a traditional builder tackling an unorthodox job where, 'the letter kills and the spirit gives life' ".

At the end of the 1970s John Pizzey left to start his own practice though he still continued to do Alistair's drawing. In the early 1980s work had dropped from plans for about 40 buildings annually through the 1970s to 12 in 1982 and 7 in 1983. The departure of John and Alistair's failing health, he had a third stroke around this time, contributed to the effective end of Alistair's design practice.

Twilight 1984-1986

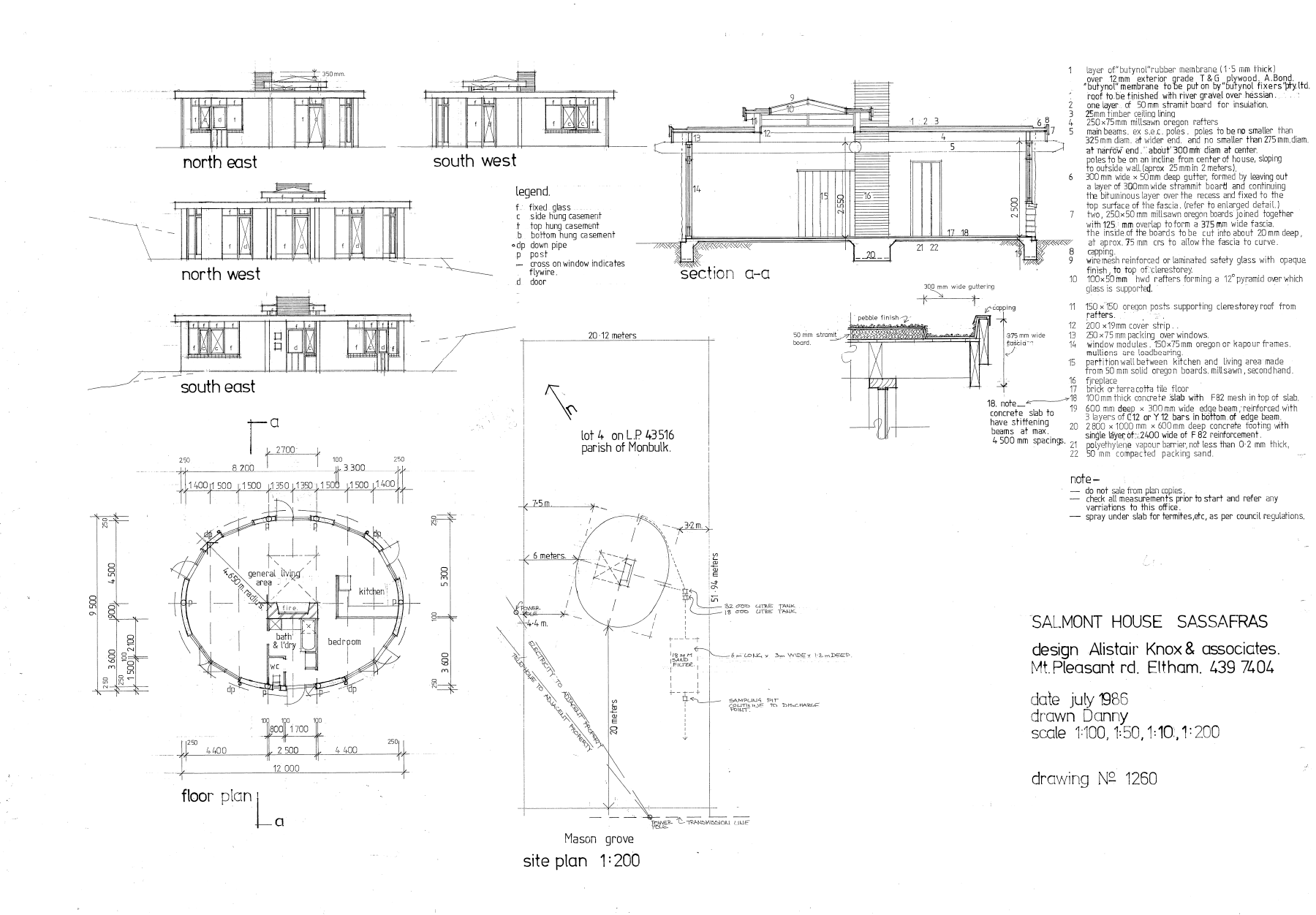

The Salmont house, Sassafras, July 1986 job number 1260. One of Alistair's last houses

The Salmont house, Sassafras, July 1986 job number 1260. One of Alistair's last houses

Alistair had virtually stopped designing when he was approached for work by a young Bodhan Kyzuk in December 1983. Bodhan became Alistair's draftsman, companion and driver allowing a trickle of new plans during these years.