Living in the Environment, Crises and Correctives

Crises and Correctives

Author: Alistair Knox

There was a business recession in Australia in 1961 that was largely due to the government's financial controls, and a stop-go philosophy, a time of correction through unemployment. The country submitted to this inequitable system because of the popular fear of socialism. The government used this persuasion to shield its own inadequacies. A fair number of business men became insolvent, and in particular, those involved in building. It cleaned out the last of the builders who were not financially stable or not sufficiently capable. The long post-war honeymoon was at last definitely over.

I had always had financial difficulties in building, firstly because the dual role of both design and construction is always complicated. Secondly, I had started with practically no capital. Thirdly, and most important, I was always involved in breaking new designing ground in both materials and construction. Being the originator of the Australian environmental building character in super-conservative Melbourne has had some strange results.

It was only by accident that I discovered about this time that I had an anonymous but enthusiastic following. Because of the financial recession across the country, and partly because I never advertised in any way, people were slow to commit themselves to taking the plunge to invest in original ideas in such a serious commodity as the roof over their heads. Despite temporary setbacks, almost everyone believed that things would return to normal and that nearly everyone would gradually get richer. The environmental issues were remote. Scarcely any normal person had an inkling of what ten or fifteen years could do in that regard. There is an inherent undercurrent of suspicion against unorthodox methods and of not putting oneself forward and placing profit before principle. There were also warnings from lending authorities about re-sale difficulties surrounding unusual buildings and methods.

This phantom following became apparent when one of my clients asked if he could open his house for display purposes for a fortnight and collect a commission for any applications that eventuated. The steady stream of visitors was less surprising than the fact that most of them knew my work well, and some spent their weekends discovering other buildings I had done around the suburbs without me knowing about them in any way. They had been at it for years and called themselves 'Knox Box' watchers.

This discovery came at a time when I wondered if it were all worthwhile. The original buildings and satisfied clients were not enough to produce a satisfactory living for myself. If clients sold their houses, they sold quickly and easily and provided good profits. The growing band of partial imitators were succeeding in this new 'environmental style'. They kept one foot in the conservative world and merely stuck environmental elements onto the traditional methods of stucture, or they became spectacular and fashionable. At the time, it was small consolation to remember that similar complications had happened to Greenway and to Griffin too. Greenway disappeared from the scene when Macquarie returned to England and there was only a low general appreciation of Griffin during his lifetime in Australia. But what is the good of an idea if you can't demonstrate it in fact?

In 1962 I realised that the continual burden of debt that pursued my building activities, but which always looked as if it were about to improve, was in fact no longer supportable. For honour's sake I was compelled to sell all the property I possessed in order to meet my bills. I took some time to do this, so I entered into an arrangement with the creditors that they waited on the realisation of these assets. They were all finally paid to the last penny. It gave me the chance to start again on a cash basis and I asked one of my employees to become a partner in the building activities whilst I concentrated on design. This meant that money I now earned from planning could be used for building a new house. The difficulty was that at this stage I had neither money nor land on which to start any such project.

One Saturday, my wife Margot and I drove around Eltham and selected the land that we felt most ideal for our purpose, although we had no idea whose it was or if we could get it. Then came the sign that I was to build again. I visited an orchardist living near the land we wanted. We asked him to find out who owned it only to discover it was he himself. Would he sell? Yes, he would. It had been in his family's possession for 114 years. In fact, he had a surveyor coming in the next day to sub-divide off the particular piece we sought.

I had to tell him that I hadn't any money at that time and I would have to sub-divide the twelve acres he would sell and that I could not help making money out of the sub-division. His answer was: 'Alistair, you can pay me when you like. I hope you make a lot of money out of the sub-division and I want you here'. He subsequently told me that it was a miracle the day that I appeared, to which I added - for me rather than for him.

I sold about seven acres at a favourable price, but it was two years before the sub-division was finally approved, and my own house had been built and established in the meantime on land on which I had only paid a small deposit.

Building this house was the re-birth of the original organic concept of the immediate post-war beginnings. It involved a return to first principle devising from what was on hand. Earth for walls, negation of concrete slabs, brick and stone paving direct onto the ground, and the employment of non-professional builders. It recaptured those early days of suntanned mud brick makers and water shortages.

The land was in Eltham, about two miles from the station and next to the orchard. It was partly cleared but still comparatively unspoiled semi-bushland. Its owners, the Andersons, had been among the original founders who came to the district back in 1849. There was no water supply available, but a gully ran through the centre of the property in a chain of water holes. I hired a sludge pump and got this rather smelly brown water into a tank. From there it was fed by gravity to the prepared heaps of earth for making adobe bricks. An enormous rotary hoe churned up good areas of land close to the house site, which a Ferguson tractor then scooped together. It was a step up on the earlier times when it was all broken up by hand.

The site necessitated a large excavation that could be so shaped and filled that it would finally appear as a piece of nature rather than man-made. The topsoil was stored for top dressing after the cuts were completed. Various tractor and scoop methods were tried to avoid hand labour which is the great problem in mud brick making. They were only partially successful owing to the stickiness of this particular material. The clay was also rather red and liable to cracking and there was a high percentage of buckshot in it. The tractor and the scoop deposited the wet earth in quantity on collapsible grids of mud brick forms in multiples of twenty-four or thirty. The idea was to ram the earth into the moulds which could then be dismantled and re-set, leaving the bricks to dry. Another problem was that, although the site was large, it soon became covered with these rectangular grids of mud bricks that made tractor manoeuvring almost impossible. In the end, they were largely made by hand by schoolboys.

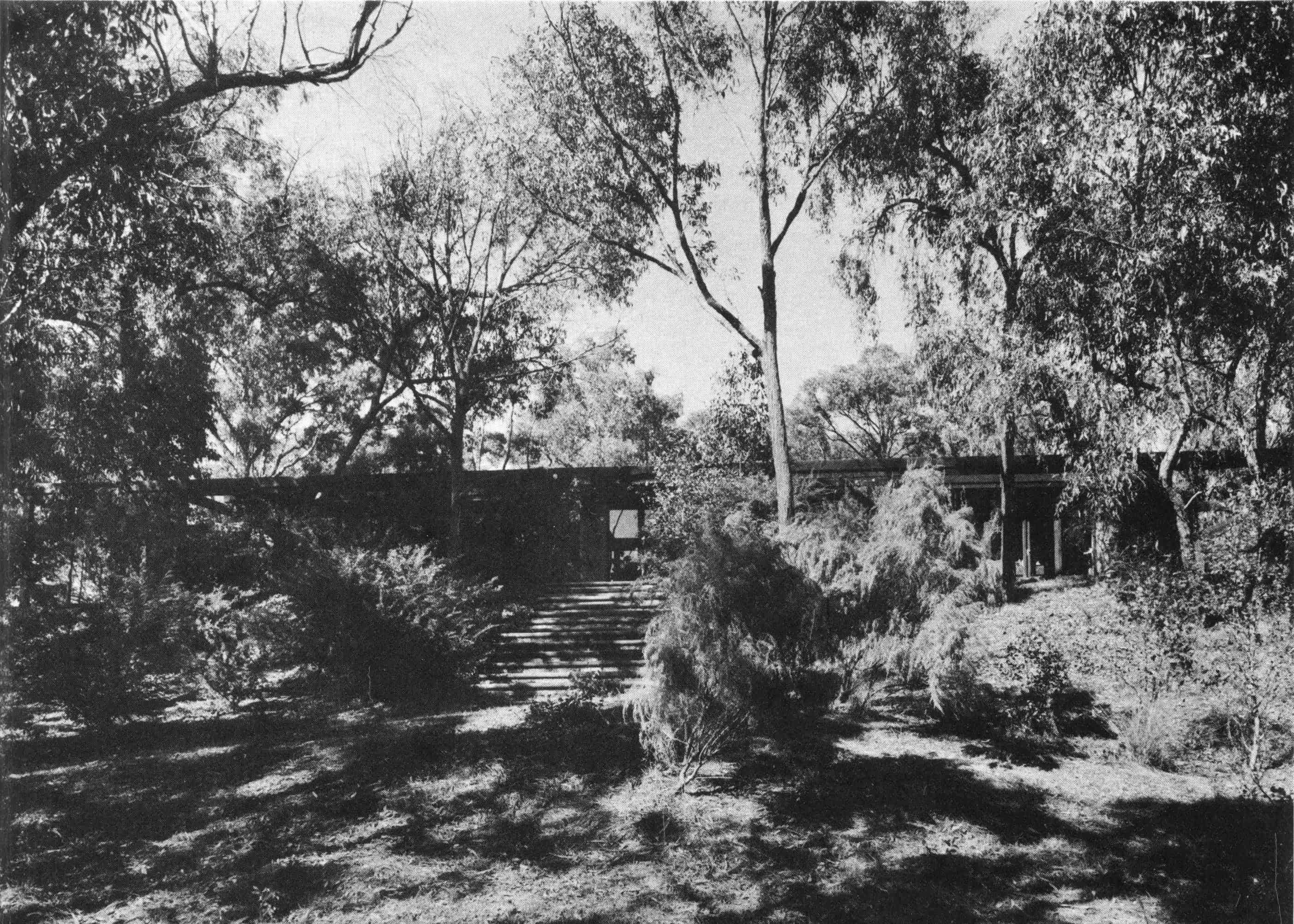

Knox house in the natural landscape

Knox house in the natural landscape

The building began late in November just after annual examinations had finished. I was running a youth group at the time and I offered them work up till Christmas. I put them under a good foreman and kept a constant watch on the operation myself. Apart from almost forgetting to obtain a building permit, shades of the old days - the work proceeded satisfactorily.

I had determined not to borrow money on this project but to rely on earnings from planning to pay for it. This led to minor crises. Looking at my bank balance one day, I agreed that if I were honest with myself about this, I should have to stop building within twenty-four hours unless some planning money turned up. None was actually due and as I scanned the list of clients I settled on one whom I thought was rather difficult but whose plans were nearly resolved. I telephoned him and made an appointment for 9 p.m. that evening. We settled the outstanding details after an hour's discussion, after which he whipped a cheque book out of his pocket and said he wanted to pay for the plans. I pointed out that they were not yet complete. This only increased his desire to settle on the spot. My hand closed over the cheque in unbelief and gratitude and I welcomed the boys at 8 a.m. in the morning in a more appreciative manner than usual.

Lionel Anette, the foreman, was capable and good humoured for the boys to work along with. He made the window frames on site from some second-hand material reclaimed from a well known architect's house that was being demolished to make way for a 'dark, satanic' commercial building being constructed beside the Yarra River nearer the city. Some of the other joinery material came from old whisky vats. It was clear grained oregon of the highest quality. When it was put through the wood working machines, it gave off a deep smell of whisky that made the whole atmosphere exotic and heady.

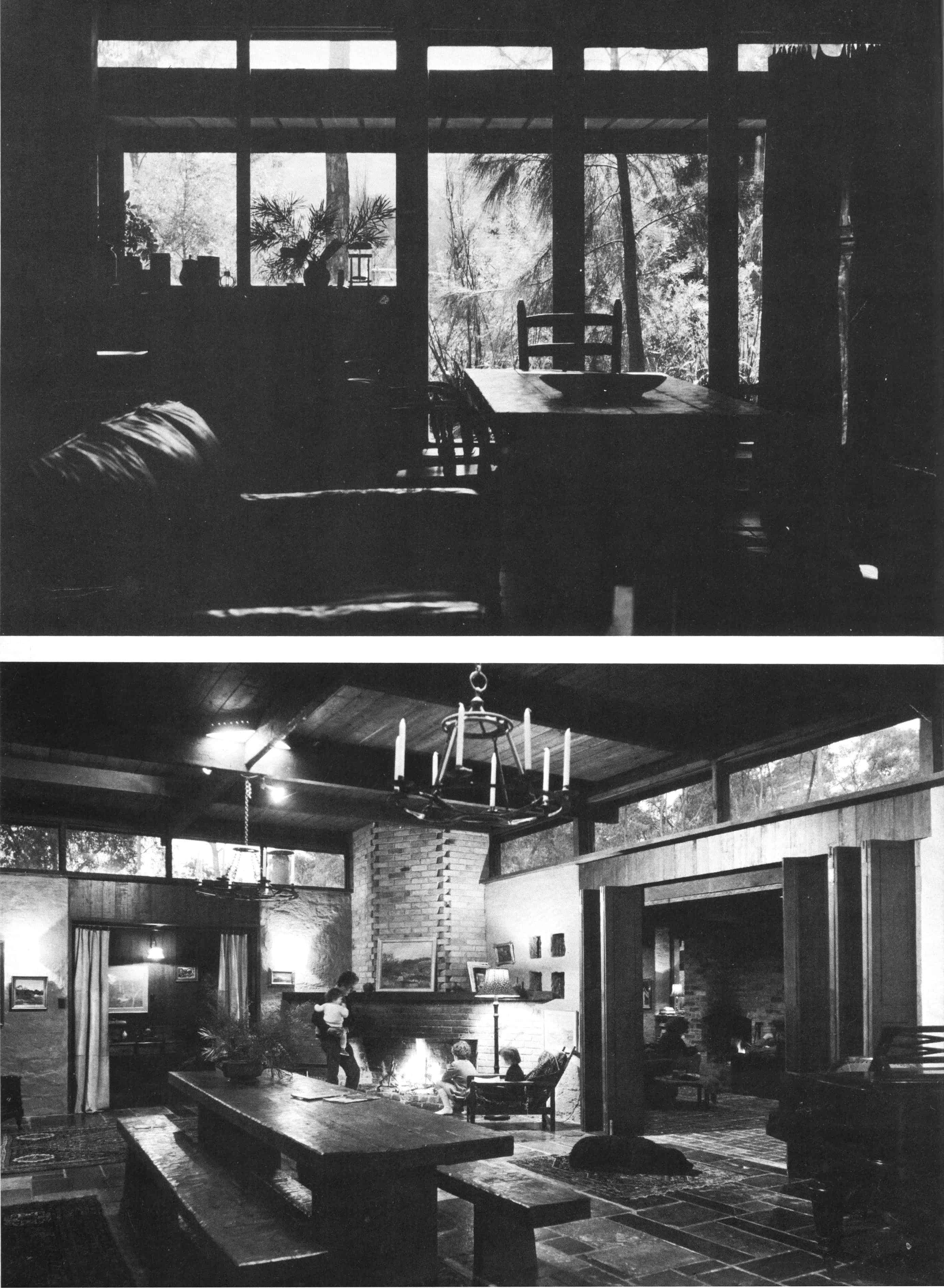

The plan was very simple. It aimed to dispense with rooms as such and to become a series of flowing spaces. Each form and proportion was as underplayed and unpretentious as possible. The layout consisted of a covered internal central courtyard, thirty-six feet by twenty-four feet, surrounded by a peripheral band of large informal zones for sleeping and living. The central courtyard area was lit by having a ceiling some three feet higher than the surrounding building. This provided clerestory windows for the mystical light and colour of the Australian environment. The four walls of the courtyard had openings of eight feet at the ends and twelve feet at the sides, that entered into the external areas. There were no doorways from the courtyard, but the splits of bullock hides were sewn together into hangings to draw across at each end of the room. A folding panel (made out of the backs of old church pews) formed a concertina door to one of the twelve-foot openings along one of the side wall openings.

The discipline of limited finance immediately started to produce an aura of inspired improvising that enabled the amateur builders to move into the problem with a new awareness that they were beating the system once more. For the past ten years I had, to a considerable degree, let go the primitive architectural character and produced over a hundred buildings using more standard materials, except for plaster. On the rare cases we did use plaster-board, it killed the environmental character of the building stone dead.

As Australia is a timeless land, the buildings in it should also be timeless. No cleverness or architectural mannerism can substitute for a humble appreciation of the unbrokenness of the surrounding nature and the interdependence of every individual thing on every other individual thing and to the landscape around them.

Concrete footings were dug and poured over the site which was half on excavated ground and half on filled ground, with piers and beams in the filled ground and normal footings on the excavated levels. Good ground levels were obtained prior to pouring so that the top of the concrete footings were horizontal and accurately related to the excavated levels. Wherever mud bricks were to go, one course of ten inch wide brickwork was laid on the concrete to act as a base to protect them from dampness and direct contact with the ground. The adjacent window walls were also raised and laid on a similar course, which at the actual door openings was varied with two inch bullnosed slate thresholds. This produced a shallow dish effect into which the floors were laid.

As there was a pergola twelve feet wide surrounding the whole building, it merely necessitated carrying excavations out to that width and laying a line of hand-hewn bluestone along it to form a definite gutter termination on the excavation side of the building. The bluestones were about four feet by one foot by one foot, laid end to end. They formed a line eighty feet long. It was all professionally wrought work and came from a building that was demolished in the original army camp site at Broadmeadows. Every First War soldier from Melbourne and many Second War soldiers must have known them.

There is a spirit in re-used material in the same as there is poetry in some words which when we use them, recall other scenes. It's not corny. It's elemental experience and the stuff of life. Buildings become timeless when they employ timeless proportions. There are tremendous 19th century materials lying everywhere around Australia where men believed that what they built was for ever. It can now often be had for a song and used as the accompaniment of new structural symphonies by another generation provided they are prepared to setout on a new pioneering society.

I first constructed only two wings of the four that were to encompass the central courtyard area because of financial limitations and the urgency of time. I had to vacate the last of our houses I had sold on a given date and I managed, without panic, to do it almost to the minute. The water was connected from more than a quarter of a mile away, as well as the sewerage, phone and electricity within twenty-four hours of the deadline. After the Christmas break I called in three carpenters from our team to erect internal walls and doors and detail out generally. These were solid timber walls similar to those in the first Le Galliennej Downing building.

The most remarkable thing about the whole project was that nearly everything came at half price, or less, and finished up having better character than if it had been the newest and most expensive available. Slate slabs from all over Melbourne somehow wended their way back to the floors and hand made bricks and similar materials, all at low cost. At one time the bricklayer complained that the remaining reclaimed bricks were not good enough, but I insisted that he use them and they proved to be the best of all in the end. When the furniture arrived on that Saturday afternoon, I was half-heartedly cleaning windows and the special 'nothing' stain the painter had applied was still drying.

The next week, on taking stock, I realised I had overspent so I determined to sit tight and do nothing until I had caught up financially. The openings into the future courtyard were temporarily sealed up. We lived in a house with only one bedroom with an open fireplace in it, a dressing room, bathroom, large kitchen and pantry, including a fire stove, and an open-air room thirty-six by fourteen feet. The two boys slept in this open room which was to be an annexe to the future courtyard room. The baby slept in our bedroom which also served as an occasional sitting room. The hub of the house was the large kitchen which was heated by a cast iron one-fire stove in winter time.

This break back from the 'compleat' house approach re-opened the original post-war spirit. There was a restoration between the immediate needs of man and the demands of nature. It was dramatic, when winter came, to stand looking out from the kitchen at the rain sweeping across the orchard next door. The stove caused the iron fountain to boil effusively till the marble in it rattled around with melodious well-being. The steam and vapour gushed out from the top of the fountain to add moisture to the atmosphere that elated the soul. Quinces picked from the trees that now stood under bare boughs had been converted into a nostalgic wine red jelly. Spreading this conserve on wholemeal home-made bread toasted at the fire created the sense of totality of the child-like nature that underlies our sophisticated pretensions. The poetry of the oneness of the eternal can be motivated by the oneness of the physical, and cause 'young men to see visions and old men to dream dreams'.

Above top: Knox house. the sense of a cave in the Australian landscape

Above bottom: A feeling of timelessness

Above top: Knox house. the sense of a cave in the Australian landscape

Above bottom: A feeling of timelessness

There was a stumbling block however in allowing the house to stay in its unfinished condition. A great stack of mud bricks had just been made for the completion of the work and they were pretty poor examples of that biblical labour. They were made by four boys, sixteen to eighteen years old. We now had the special privilege of a good water supply. The weather was very hot so I arranged that if they made 200 per day between them, they could finish as soon as they were completed. This was usually about 10.30 a.m. This batch of bricks were moulded in grids of thirty and the grids had to be washed down between settings. The hose going at full bore washed down those boys as well. They stood laughing uproariously, dripping from head to foot the whole time. The bricks came out more or less in one fairly regular shape but the mixing of the material was just passable. When they were dried and stacked, there was considerable doubt as to whether they would stand the winter in the open, as any self-respecting mud brick should.

The footings had been poured for the whole of the house and the window frames were standing so I decided to start laying the walls myself. Each day I would put down sixty to eighty bricks and mostly the effort convulsed me with thick asthmatic breathing which was a legacy from the financial tensions I had been through a year or so earlier. I got so stiff and weary that I could hardly push a pencil without moaning and my mind also seemed to ache with physical tiredness.

One Saturday afternoon I was sitting alone, gazing out of the kitchen window, wondering where to go and what to do next, when a blue Volkswagen car wound up the road into the drive. A figure emerged whom I had seen somewhere before. He approached me and asked if I would employ him. When he told me the work he had done, it took me only moments to readily agree for him to start the next Monday.

Eric Hirst then took over the whole of the remainder of the house building. He worked on it from that day until everything was complete a year later. The additional sewerage, slate paving, brick laying, external paving, carpentering, tiling - all were handled .with equal ability, even down to recovering the billiard table. He was born in Yorkshire where he worked early in his life on old medieval buildings in that area. The work he did so well for me was of the same character, involving spatial relationships between man and nature.

The harmony of necessity and knowledge is the main factor in environmental building. It should be true and inevitable and free from man-imposed details. Honest materials and true proportions speak for themselves for all men at all times.

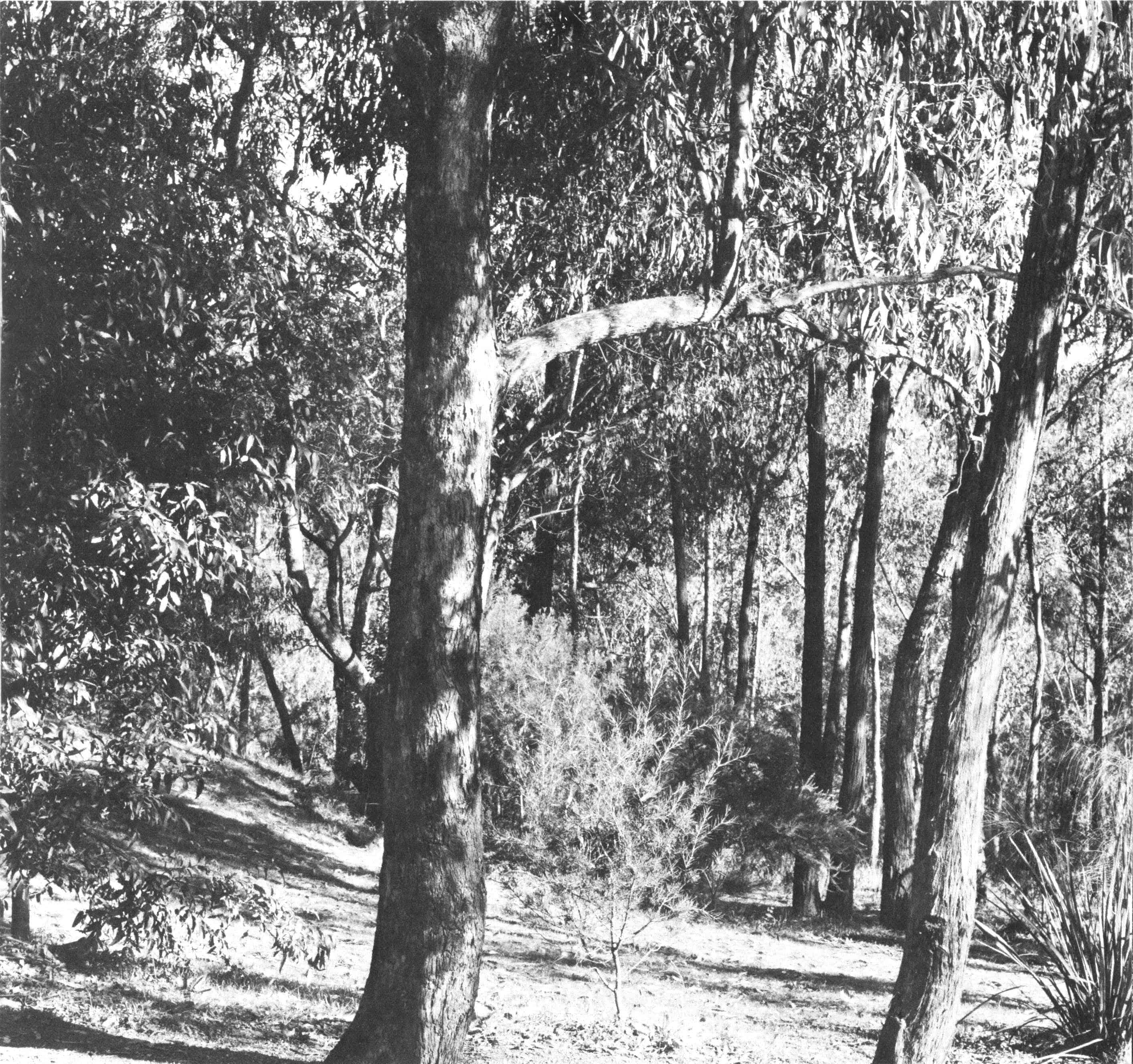

Knox house: piers and pergolas

Knox house: piers and pergolas

The day the building was finally completed, it was opened for inspection along with a couple of other houses I had recently finished, for a charity viewing. More than one thousand people walked through it that afternoon. There was a great sense of fulfilment in all this. The wonder and delight that people experienced was undeniable. Perhaps the most significant fact was that Australians who came kept telling me that, it reminded them of a great house they used to know in the Dandenongs or in the bush where they went when they were little children. Continental people were equally convinced that it was inspired by some castle in the Bavarian forests. To me it meant that it was saying something fundamental to everyone. It had created its own sense of eternity.

One interesting fact was that a journalist from the newspaper The Times of India, who happened to be doing a six weeks tour of Australia for his paper, was among the visitors. The next week a long article appeared under his name in the Australian. It spoke of Prime Ministers and other national figures. Right in the middle was a section on Eltham. I had noticed him among the heterogeneous one thousand people but I did not know who he was. He stated that he was impressed with what he saw and finished in amazement of the immense open spaces of land around the house and the district. 'How long can it all last,' he wanted to know.

Ten years later I believe it is possible to say that a balanced relationship between man and nature in Australia could last indefinitely, despite the present urban phenomena of Sydney and Melbourne. The prospect of the new towns and the tremendous change in thinking towards conservation and environment have perhaps arrived in time to allow for the depredations of the past to be rectified.

It was so easy to slip back into what we had been doing fifteen years ago. The Eltham scene had never lost its relationship with the mud brick and now the children of the original builders were old enough to work themselves. The first evidence of the young drop-out society was just becoming apparent. Natural building was a catalyst in the alternative society concept.

Dreary governments inhibited everything worthwhile and adventurous because it intetferred with the status quo and required an effort of will. It did not help the rich. Why rock the boat while the land lay supine and under the illusion of a false prosperity for all? The boredom in the materialistic society was still being dampened down by the endless flow of new innovations that really altered nothing but managed to keep the mind off that unpalatable fact.

It is the directness of environmental construction that is so inspiring, when coupled with the chance of getting imaginative materials at low cost, and can result in a new way of life. It is not the building itself in the end but the rediscovery of joy, wonder and fulfilment that exercises the whole man. This is particularly apparent in the present technological demagoguery.

The early Australian had to pit himself against flood, fire and destitution. Thank God that that grinding conflict has now gone. However, there is in the midst of abundant opportunity another conflict that attacks those who suffer defeat through age, sickness and the like, that is almost as bad.

The environmental inspiration that occurs in natural building regathers the breadth of the past way of life without the manipulation of the technocrat. Although it is open to all, it is probably true that the experience of being oneself in the landscape will remain the privilege of a comparative minority. It takes belief and a readiness to embrace simple living, even if it doesn't go as far as Ivan Illich's voluntary poverty. It will however give that minority the advantage of seeing things whole and seeing them clear. It makes men complete instead of cutting them into sections the way materialistic society does.

Our twelve month climate and elemental landscapes have a better opportunity to express this belief for life than anywhere else in the world. It is not a lotus land. You won't smoke too much pot out in the red heart. It requires a self-imposed discipline, and an inner reliance to restore and justify our existence.

Our new house landscape at Eltham was an integrated series of simple plantings and land shapes. The whole object was to make it seem as if it had all happened centurie.s before through the repetitive cycles of growth and renewal. The Australian scene is monotonous to some casual observers because they have not experienced how subtle these eternal cycles are. The landscapes are not spectacular, they are profound. A slight change of colour in the foliage can sometimes say more than the most spectacular fall of a northern climate. The forces of power and sunlight at work cause a spirit of survival consciousness to be apparent to those who have experienced and understood them. The sense of wonder is total, free from the intervention of man. It is the heart of creation reduced to its simple elements. Each shape, each colour, is interdependent

Knox house: sculptured landscape. 'The sloping bank of the excavagtion was graded back to the greagest possible degree ...'

Knox house: sculptured landscape. 'The sloping bank of the excavagtion was graded back to the greagest possible degree ...'

on each other shape and colour to create a totality of the visual world around us. In e:3Sence, the Australian landscape should use the indigenous plants only and allow the whole breadth of the scene to be felt. Tinder dry bark, fallen leaves and the scent of the bush in the vertical rhythm of the eucalypts is written into the heart and inner being of every genuine Australian. No matter where he resides in the world, no matter how successful, he has only to smell a few gum leaves burning to recall the shimmering heat of the brown paddocks, the greyblue-green eucalyptus forests, or the blue horizons of the sea seen through the banksias and the ti-tree.

Although environmental design sees the indivisibility of house and land as the chief factor, I have cheated on the landscape by bringing in Australiari plants (which are unique in every sense) from other parts of the continent. The Eltham bush is basically composed of stringy barks, yellow box and candle bark varieties of eucalypt and the wild cherry. Black wattle and smaller ground cover, including delicate orchids and innumerable wildflowers fill in the spaces. Nearby there are red box stands and a few miles further on the great iron bark, symbol of the auriferous gold mining country. In the wet valleys, some great red gums still grow to enormous size and age. Perhaps it is the iron hark and red gum which speak most powerfully of all, but each variety and species so complements the next in the unbroken scene that it is finally impossible to' separate them.

The spirit is captured in an exaltation of wonder, mystery and inspiration at the creator. One identifies with all life, all time, and all creative forces. Introducing she-oaks, grevilleas, banksias, melaleucas into a landscape of five acre", reduces the scale in one way but it is justifiahle because it enlarges the dimension and subtle variety of all natural things.

It is the hot summers that most clearly express the land. The ever-present threat of bush fires borne by the north winds is a force one is always aware of, and the droughts that result in a gradual withering of the landscape. When the rain finally falls on the petrified bush floor, it sounds like the rush of a relieving army. Nature revives in a moment. The cries of birds and animals fill the air. One is conscious of a sound like the deep beating of a giant heart of the universe in this balance of the bush, the water and the sunlight. On the purple summer nights there is a quality of listening silence. The moon strikes through on to the white and naked trunks of the candle barks as all nature rests awaiting the immutable struggle for survival of the next day. Microscopic movements among the gum leaves, that hang edge on to the sun in order that they do not dehydrate during the day, allow the stars in their constellations to be seen practically anywhere in the bushscape at night. The content of oneness envelopes everything.

Developing an Australian landscape is more a matter of leaving what is there than of digging and planting new things. Much of the soil and bush area is deficient in various trace elements which automatically creates a survival conscious power in what survives. The prime requisite is observation of the surrounding natural countryside modified to accept the intrusion of the house. It is a matter of what the landscape is saying to us, rather than what we are saying to the landscape that counts. All Australian foliage is sympathetic to the Australian scene and practically no introduced plants are. Perhaps some from South Africa, a few from the Pacific and South America, will get by. But why introduce anything into such an existing unity? The basic rule of never using two things where one will do in the environmental building design also applies to the landscape. One is continually surprised to find just how few people understand what it is all about. It certainly has nothing to do with 'Beautification' or. even beauty per se. Its sense of eternity transcends the best aspirations of man. Those who most understand the Australian landscape are those who leave it most alone, those who are inspired by it and not by those who try to transcend it.

We left the landscape surrounding the house in as natural a state as possible. Where the mud brick makers had scarred the land, we regraded and replaced the original topsoil that had been set aside at the beginning. The sloping bank of the excavation was graded back to the greatest possible degree so that it looked like an act of nature and not of man. Top soil was spread back on it a couple of inches deep and the exact grass of the bush was re-sown on the banks. Trees surrounding the site were left in the mounded areas where they were higher than the house site and they were filled around where they were lower. Some trunks were buried five or six feet in the fill. The pundits of course said the trees would die but they didn't. It may have been due to the bark getting a bit knocked about with the bulldozing and the trunks re-rooting above the normal ground level. The primitive trunks of eucalpts could make this quite possible. A couple of weeks after any bush fire, they send out thousands of leaves from their straight boughless stems to keep the tree alive until it restores its natural cycle. Where the scale of the landscape has been broken, the varying effects of rain, soil and other elements affect its dimensions but not its character. All man-made interpolations on a landscape reduce its scale. For this reason the art of environmental landscaping must consider how best to recapture the illusion of the limitless within the limited dimensions.

The 18th century English school of informal landscape design is unquestionably the model to follow. Kent, Brown and Repton all employed in one way or another the sculptured landscape in three dimensional masses and two dimensional voids. The artistic relationship of these masses and voids, structured landscape of mystery and wonder, has been enhanced by the succeeding centuries. So great was Brown's capacity to redesign the whole scene that he was virtually lost to posterity as a landscaper for many years. His work was so fundamental that those who succeeded him thought it was the work of the original creator himself.

In the Australian informal landscape this means clump planting within interrelated spaces. Where possible, ornamental water can be placed to develop a sense of well-being in the colour and light atmosphere of the water hungry continent. Clump planting of bush trees and over-planting natives, causes them to grow better than if placed as specimens. Although individually beautiful, Australian trees are not basically specimen type trees but part of a whole antediluvian landscape of mood and totality of vertical rhythms and horizontal planes. Dust and heat and dry shimmering distance where the operative word is 'power' - the power of the red gold colour of a violent sunlight. Indigenous landscaping consists of the handling of these total conditions through recurring seasons. Australians are one man from Cape York to Hobart and from Fraser Island to Shark Bay, because the forces of nature extend unbroken through those distances.

At Eltham we encouraged every seed that struck naturally around the house to grow where it germinated. This is bringing about the restoration of true bush conditions. It is so natural and unplanned. that it does not feel like conscious landscaping at all. As this developed, there sprang up with it a new awareness involving an alternative society, that is an accepting of things as they are and using them as they come. It is the instinctive reaction to the over-organised systems that have gripped both commercial world and urban community everywhere.

The real outback Australians, by virtue of the struggle for survival, were men with leathery faces and far-away eyes. Tough and resourceful on the one hand, wistful and gentle on the other; slow, soft spoken and drawling voices befitting the enormous spaces of their environment. They contrast strangely with the noise pollution of city and suburb so filled with the surging swish of automobiles and twenty-four hour flow of an inane gabble from radio and television.

The original landscape is both survival conscious and fragile, which the bushman knows and respects. Man's interference easily destroys this context by regarding its primitive shapes as mere scrub and missing its sense of genesis. Australian landscape architecture is first and foremost the recapturing of a reverence for the visible hand of God through the whole picture. It has nothing to do with the international methods and man's fashions. It spirit is grounded in the eternal.

Ellis (Rocky) Stone, father of natural landscaping in Australia, gained his design and experience instinctively while shooting foxes as a boy in the Euroa district. He would wait beside a huge boulder so characteristic of that famous Kelly country, looking down the winding track waiting for the quarry to appear. Thirty years later, when he was first asked to do some landscaping with boulders, he remembered how it was back in those Euroa days and placed them just like that.

Australia is still an open society where every concerned man may get down to his own thing within the broad confines of the unchanging triangle of the land - water hunger, survival consciousness and the power of sunlight.

Our own rebuilding programme created a demand for this alternative building to the current materialistic style based on cleverness and the personality cult. The new house opened an opportunity for those who had a hunger for local character in building but had never .seen it nor had the ability to express it. Environmental building is not as economical as it once was and the effort of getting those first earth buildings under way again after so long an interval was still exacting and time consuming. One had to accept the grind of the medium in order to achieve the end. However, experience did relieve the trauma that once used to occur when nervous clients saw vast areas of their land covered with cracked and drying mud bricks for which they were being asked to pay good money. The early hit and miss mud brick making process required faith and tenacity that was alien to the emerging society immersed in the struggle for security in those earlier years. Now the security had come and the struggle had finished but they were still unsatisfied. In accepting the ease of prosperity as our right we forgot the value of the struggle. The children of the fifties were observing and disapproving of their parents' self-centred values and this reacted on the parents. But it was much more than that.

The mud, solid timber ad zed posts, light and shadow contrasts and powerful proportions all identified themselves with the landscape around them. They said something to us as individuals and also as members of a national community.

Our own house had a series of two feet by two feet mud brick piers occurring at modular intervals around the entire outside wall line of the building that were a dominating form. It was Greek pier and beam design with a three-tiered horizontal roofline consisting of pergola and verandah level spreading out all round, tying the building back into the bush. Next, the general roof level which was again surmounted by the roof covering the inner courtyard. The lighting created by this change of level provided the traditional spirit of the landscape.

To my mind, the Greek expression of the relative form of the piers and beams seemed exactly right for a landscape that has a horizontal plane and a vertical rhythm, just as it is interesting to note how much drawn Australian travellers are to Greece. I feel it is not only the fashion or the cheap living, but the fulfilling and longing to find a counterpart to the half-understood principles of their own landscape.

The large piers of mud that divided the window walls that again had timber verticals about two foot six inches spacing along the whole of their structure, expressed in an unobtrusive way something of the large, well established treescape around the building. The verticals in the window walls said something about the recent sapling growth. It was structure identification with the land to give the sense of indivisibility.

This element of Greek mythology was apparent in the late 19th century impressionist painting of Australia, particularly in Tom Roberts. The shearing sheds he painted were constructed from the trunks of large trees. There were heroic shapes about the shearers and the sheep recollective o[ sculptings across the entablature of the Parthenon. The painters in their day were expressing Australia Felix. They painted thus during the rise of nationalism which preceded Federation. No sooner did it become a reality than they set off for Europe to lose much of the special inspiration and oneness the ancient land had provided them with. It has taken us a long while to decide to be our own men again and to withdraw from the dependence upon European culture. This is especially so when we remember how we came to inhabit the land and the defiance of many of the early settlers.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >