Bohemian Associations

Biography

1912-1929Childhood

The Bank

1930-1939

Adolesence

Marriage

1940-1949

The Navy

First Buildings

Bohemian Associations

1950-1959

Early Houses

Margot

Professional Building

1960-1969

Hard Times

Knox House

Landscape Architecture

1970-1979

Helping Hand

Eltham Shire Council

Mature Houses

1980-1986

Postscript

Alistair's introduction to Melbourne's 'art world' came when he attended Art Gallery night classes at the Public Library Building. There he met Sam Atyeo and through him the bohemian side of the city's society.

Cynthia Reed, 1945

Cynthia Reed, 1945National Gallery of Australia.

There were one or two places where artists and art potters - art pottery was still in its infancy - would always meet, notably the Primrose Pottery in Little Collins Street. When I first visited there in 1932 it was run by Cynthia Reed, John Reed's sister, who was later to marry the famous painter Sidney Nolan. Sam introduced me to this scene because he was just starting to design modern furniture. I found Cynthia vivacious and attractive she made me wish I were ten years older. The George Bell Painting School was then in vogue, and men as diverse as Arnold Shore and Russell Drysdale were moving away from the traditional scene, though they still constituted but a minority group when compared with the traditionalists.

After his girlfriend Peg Lord went overseas he met his first wife Mernda Clayton and through her was introduced to the world of creative-dance. But marriage and somewhere to live took precedence.

He joined the Naval Auxiliary Patrol 1943 and spent two years in the waters around New Guinea. On his return and the collapse of his marriage, a casualty of war, he become more involved with his old friends.

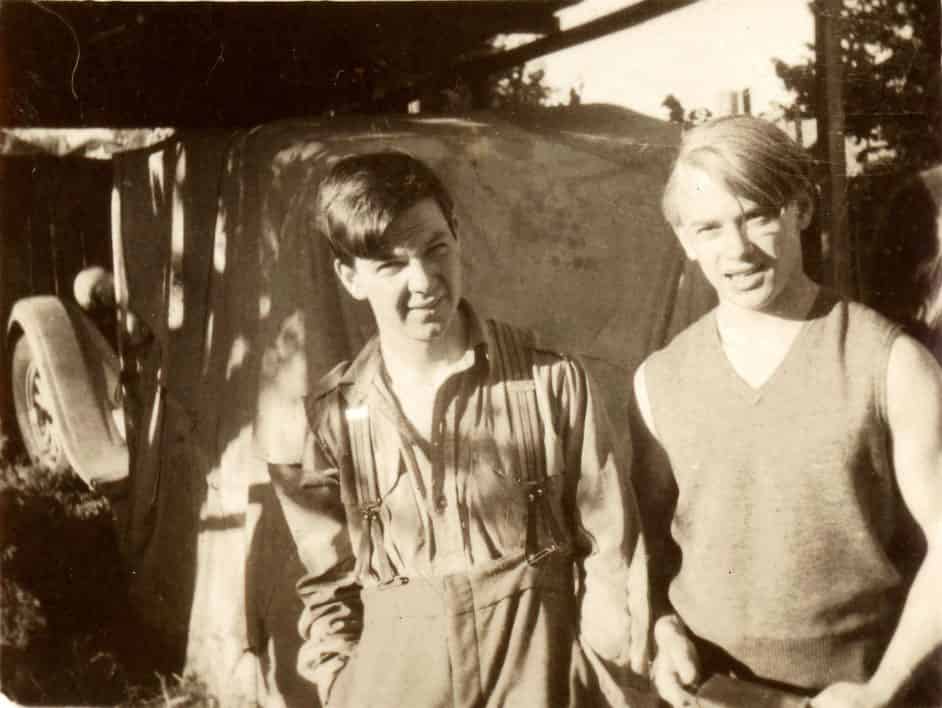

Arthur Boyd and John Perceval in front of the family Dodge at Open Country

Arthur Boyd and John Perceval in front of the family Dodge at Open Country Photo: Albert Tucker State Library of Victoria

The New Art movement - at whose birth I had been present thirteen years earlier - was, however, in healthy condition, even if its members were beset with financial difficulties. Arthur Boyd, John Perceval, Sidney Nolan, David Boyd, Neil Douglas, Bert Tucker, Matcham Skipper, and others who have become part of Australian history were on the threshold of their careers. I was still at the bank, but I could escape early enough most afternoons to join all of them at Ristie's Coffee Lounge in Elizabeth Street for afternoon coffee. Coffee cost a shilling a cup - about all the loose cash we could afford. These were most stimulating get-togethers, particularly when we were joined by Uncle Martin - David and Arthur Boyd's celebrated writing uncle Martin Boyd - the author of Lucinda Brayford and other famous Australian novels. Ristie's evoked the spirit of the new age in Australia. We looked beyond the fact that the country had, due to its geographical position, been an intellectual backwater.

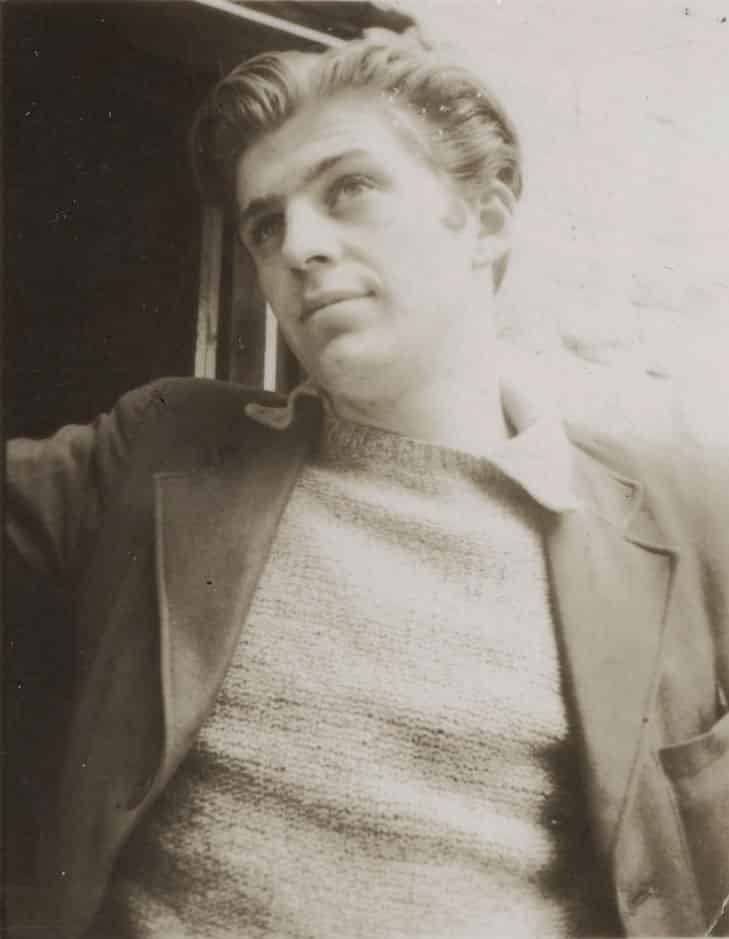

He started a part-time course in Building Construction Practice and Theory at The Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, then Melbourne Technical College. On the first day there he met Matcham Skipper and through him gravitated to Justus Jogersen's artists colony at Montsalvat, Eltham.

Matcham Skipper in the early 1940s

Matcham Skipper in the early 1940sPhoto: Albert Tucker State Library of Victoria

I was out nearly every night of the week. ... On Tuesdays and Thursdays between 4.30 p.m. and 6 p.m., we all crowded into Mr Jorgensen's Brown Room in the picturesque Mitre Tavern off Collins Street. Melbourne's licensing laws were then prehistoric and known as the 'six o'clock swill'. The bars closed at that precise moment. They were generally filled with a jostling crowd of half-inebriated workers trying to consume two or three pots in ten or fifteen minutes before they went home or the police started to herd them out of the hotel doors. The floors were generally awash with spilt beer, and the dishevelled appearance and the wild eyes that gazed uncomprehendingly from the other side of the bar were the best possible justification for saner licencing laws. Jorgie had for many years enjoyed the privilege of a private room at the tavern for those two evenings each week when he taught at his nearby studio. It became the nexus of artistic bohemian Melbourne. Beer was a shilling a glass. Trays full of glasses would be purchased at the bar and carried, through the jostling mob, to the private room to be consumed in somewhat more orderly surroundings. Jorgie always occupied a brown leather armchair in the corner, receiving and acknowledging greetings from all who were permitted entry, which depended on their knowing him or some of his pupils.

At closing time, the hotel always rang an aggressive electric bell to advise the drinkers that the law prevented them taking any more money from customers for that day, so they must hurry and get out lest they be charged for being on licenced premises at a prohibited time. Most of the habitués of the Brown Room would proceed to the Latin Club at the eastern end of the city for the evening meal. Little time would be lost reaching this venue, where wine could be consumed with meals until 8 p.m., at which time the long arm of the law would descend and remove the bottles, with the food only partly eaten. The rapid beer session, followed by half a dozen speedy glasses of claret, left the face flushed and the heart palpitating as at the conclusion of a race. The new age was noted much more for energy than for grace in its social activities. The drinking of vast quantities of beer had been the prerogative of the Australian male throughout the history of the continent; but with the postwar financial freedom, wine began to become popular. Places like Jimmy Watson's, located near the University, established a clientele who drank claret while they barbequed their steaks out in the garden. But there remained an undertone of frenzy surrounding the consumption of alcohol as it became the prerogative both of respectable, law-abiding men and women and of the dungareed labourers drinking great pots and claiming, 'They allus has one at eleven'.

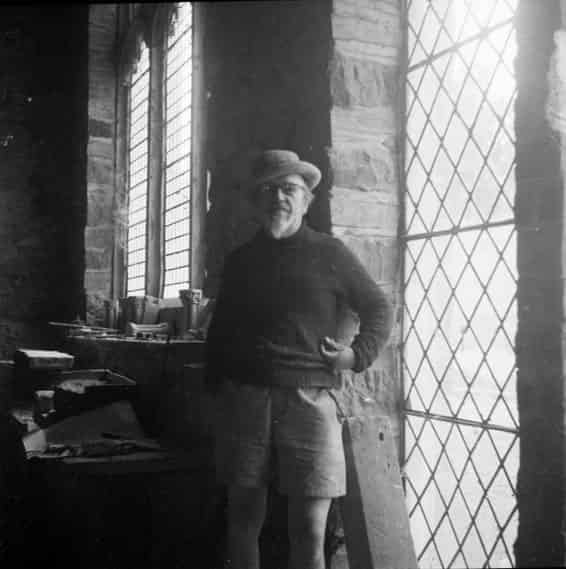

Justus Jorgensen at Montsalvat

Justus Jorgensen at MontsalvatPhoto: Sarah Chinnery photographic collection National Library of Australia

In 1947 I became a regular visitor to Montsalvat, the Artists' Colony, which had gone back to completing the great works it had begun in the 1930s. Justus Jorgensen had welded his pupils into a close-knit organism. Despite his despotic attitude, he introduced them to a freedom that the general community was just gaining a hint of more than ten years later. They called him all sorts of names, deplored his egocentricity, and simultaneously defended him against all outside criticism. His ability to maintain his opinions against all assaults won his pupils' unswerving allegiance and their frustrations, at the same time. He demonstrated his building and design ability every day as the work proceeded, irrespective of the observers' personal opinion of it. It could not be denied. He encouraged the rich to become patrons of his great 'dream', and the poor to do the building. The theme of a French village on the west side of the hill dominated by the Great Hall prospered, while a fifty-five-foot sailing scow made its appearance in the top paddock looking like a modern ark waiting for unpredictable events. The lack of conventional materials directed me towards mud-brick building, which I thought would be both possible and cheap. I became friendly with Sonia Skipper, Matcham's beautiful sister, who was a great builder as well as a painter, a sculptor, and a person accomplished in all the artistic pursuits. Her equable nature contrasted favourably with Helen's - her somewhat vitriolic older sister's - and her brother Matcham's deviousness. Helen had become Jorgie's mistress more than ten years earlier and had borne him two childrenâ??Sebastian and Sigmund. Sonia had a daughter by Arthur Munday, who was a solicitor who had given up his practice to become a full-time member of the colony. Jorgie preached adventurous living - and certainly practised it in the keeping of his wife - Dr Lily Jorgensen - and Helen Skipper under the one roof for many years. Helen was the young and beautiful daughter of Mervyn and Lena Skipper, the original family who left their Eaglemont house to join in the beginning of the escape from the suburbs into a new freedom. Mervyn was the editor of the 'Red Page' of The Bulletin when that weekly was the major Australian literary journal. He was also a well-known writer in his own right and Lena, his wife, was an exceptional woman and mother of the three brilliant Skipper offspring; throughout the remainder of her life, she remained a central figure in the history of the colony.

In 1946 the size and importance of a party was gauged by the size of the barrel of beer around which it was set. A niner cost between 3 pounds and 4 pounds and was adequate for a dozen guests, with a bit left over for the next day. An eighteen-gallon keg indicated a local gathering of some significance. It was important that the barrel be correctly opened, because a loss of gas would mean flat beer. Broaching the barrel became the responsibility of those more experienced partygoers who could successfully insert the bung without losing the pressure. Beer was Australia's most universal social stimulant, and considerable conversation generally took place as to which State provided the best. The artists' parties consisted mostly of young creative men who had just begun to be recognised after the war. They were mostly ex-servicemen and able to consume vast quantities of alcohol because they were in good health and had developed the drinking habit expertly during their war experience.

Danila Vassilief's working on his Warrandyte house, Stonygrad

Danila Vassilief's working on his Warrandyte house, StonygradPhoto: Albert Tucker State Library of Victoria

When Danila [Vassillief] decided to have a party in 1946, his studio house was in the first stage of its development, still uncompleted. Some of the guests were taken to the venue in the Boyds' Dodge - which by had now achieved some degree of reliability, so that any doubts about getting there or fear for personal safety were dismissed in view of the importance of the occasion. The studio was situated in a heavy-bush environment close to the Yarra and was quite difficult to find without some clear directions. The party occurred on one of those perfect nights which are the crowning glory of that sacred wedge of colour-and-light magic that formed the heartland of Australia's Impressionist painting movement. Danila's romantic Cossack background and the balmy bush effulgence combined to produce an unforgettable atmosphere. Everything returned to normality only after all the beer had been consumed and the morning star was high in the heavens. No one knew exactly what had happened, but when we left to go home there were more than twenty prospective passengers struggling to board the Dodge and get a ride back to our house at Heidelberg. David Boyd's Byronic figure occupied the driver's seat; the rest of us stood up, hanging on to each other and to any protuberances that might offer support. This made the centre of gravity very high and dangerous, because the hood had been folded back to permit us to stand. The narrow, unmade bush-track and precipitous grades combined to make the journey extremely risky, but we were so busy holding on to one another that one danger drove out the other. After about a mile of this insanity, there was a sudden explosion when one of the tyres blew out. Only David's driving skills prevented us overturning. We finished up half in the bush, between some trees on the other side of the road. There was no alternative but to leave the car and proceed the seven miles back to civilisation on foot. After a time the first streaks of dawn appeared and revived our flagging spirits, but it was after eight o'clock when we finally rounded the Bulleen Road/Banksia Street corner where Heide was situated and looked along the river which led over the bridge to our establishment in Mossman Drive nearby. The little white house with its light-blue shutters was a welcome sight to the entourage, who had spread out over five hundred metres like a defeated army retreating from the battlefield. People occupied the beds, couches, and floors according to the order in which they made it back.

Many of Alistair's friend from this world became the builders of his first houses.