The First Houses

Biography

1912-1929Childhood

The Bank

1930-1939

Adolesence

Marriage

1940-1949

The Navy

First Buildings

Bohemian Associations

1950-1959

Early Houses

Margot

Professional Building

1960-1969

Hard Times

Knox House

Landscape Architecture

1970-1979

Helping Hand

Eltham Shire Council

Mature Houses

1980-1986

Postscript

Reporting back to Head Office to resume my peacetime occupation was extremely difficult and far-removed from my idea of what I hoped the 'fruits' of victory would be. I was re-incarcerated in a marble mausoleum where I was required to attend to the simple financial requests of the solid Melbourne bourgeoisie. They were always polite, and my co-workers were always helpful and efficient. There was never a cross word spoken; but the repetitive certainty of each day and the exactitude of one's weekly remuneration were the next-worst thing to solitary confinement, especially as the pay had become less attractive than it had once been, and the work more intense. A new world was dawning all around us: the old values of security and superannuation were being superseded by a new sense of excitement and adventure.

It started for me in 1946 when I enrolled at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology to study. The Chifley Government provided free tertiary training for every ex-serviceman who would apply for it.

Enrollment day at the RMIT saw about two hundred applicants crowding into the Architecture School to be assigned to their study groups. I had done part of Year 1 Building Construction Practice and Theory in the navy, by correspondence. Because of the great number of first-year students - and as my drawing looked adequate - I was placed in Year 2 of the architectural course for those all-important subjects. The reason I was choosing building and design as a vocation was that I was naturally drawn to it as an art, a philosophy, and a science. The sets of chisels, saws, and hammers with their beautifully polished handles that I had learned to use in Uncle Jim's workroom as a child - these made the mechanics of construction appear very simple. I saw it merely as a matter of putting one thing on top of another. Design methods were related to the comprehensive principles I had learned from my father and the instinctive practical skills I had inherited from my mother.

The Lippincott house in 1922. It was designed by Burley Griffin for his brother-in-law. The large river red gum stood in the front of the allotment on which Alistair Knox built the family house 20 years later.

The Lippincott house in 1922. It was designed by Burley Griffin for his brother-in-law. The large river red gum stood in the front of the allotment on which Alistair Knox built the family house 20 years later.Photo: from the Eric Milton Nicholls collection, National Library of Australia

Nineteen forty-six was a tumultuous year. Even before the mid-year tests at the Institute of Technology, I was planning to build my first house (for sale) on some land I had bought for about 100 pounds a block in the Glenard Estate, of which our own house formed a part. It was some of the least attractive land in the estate and faced onto the Glenard Homestead, but it was open in character and contained two or three ancient redgums. Hitherto I had never had any reserves of money. Even my bank account seldom showed a credit balance of more than a few pounds. Our war-time trading activities, however, had changed this notion of money for me. It was now quite respectable for a bank clerk. I persuaded Norm Ellis, a co-member of the Martindale; Freddie Watton, who had joined the NAP the same day I had; and John Pitt, who had joined up a little earlier, to each contribute equally to obtain six blocks of land for the minuscule sum of less than 700 pounds.

There was a whole new demand for building as Australia saw its vision of prosperity extending endlessly into the future. The deferred pay the servicemen received on demobilisation, along with the pent-up repressions of the past difficult fifteen years, provided opportunities that had never been seen before. The only problem lay in the lack of materials. I had, however, sold the first site - complete with house plan and a cost-plus contract to build - in the first half of 1946.

The Bryning House, 1946, showing Matcham Skipper's chimney and John Yule's stone wall

The Bryning House, 1946, showing Matcham Skipper's chimney and John Yule's stone wallPhoto: Australian Home Beautiful. Post War Study Stage 1, Vol 2 Residential A, Dept Planning & Community Development

The shortage of building materials became more acute as 1946 proceeded and the incipient plans of thousands started to crystallise into action. Our little building group of four got off the mark fairly quickly and obtained its first building permit for Noel Bryning's and Bobby Burns's house while there were still some building materials available. The house was a simple timber construction with integral verandah and pergola extensions that were well ahead of current methods; but the great advance was to weld these extensions into a great redgum tree - an unheard-of innovation in suburban Melbourne. Bricks were very hard to get, so we decided to build the massive fireplace, as well as some garden and terrace retaining walls, of Warrandyte stone. The building used stumps and bearers and included a change of level between the living areas and the bedrooms. As materials became even scarcer, reasonable labour costs seemed to vanish altogether. The demand caused a rapid rise in the prices and the hardening of black-market prices, all of which seemed to circumvent detection and prosecution with ease.

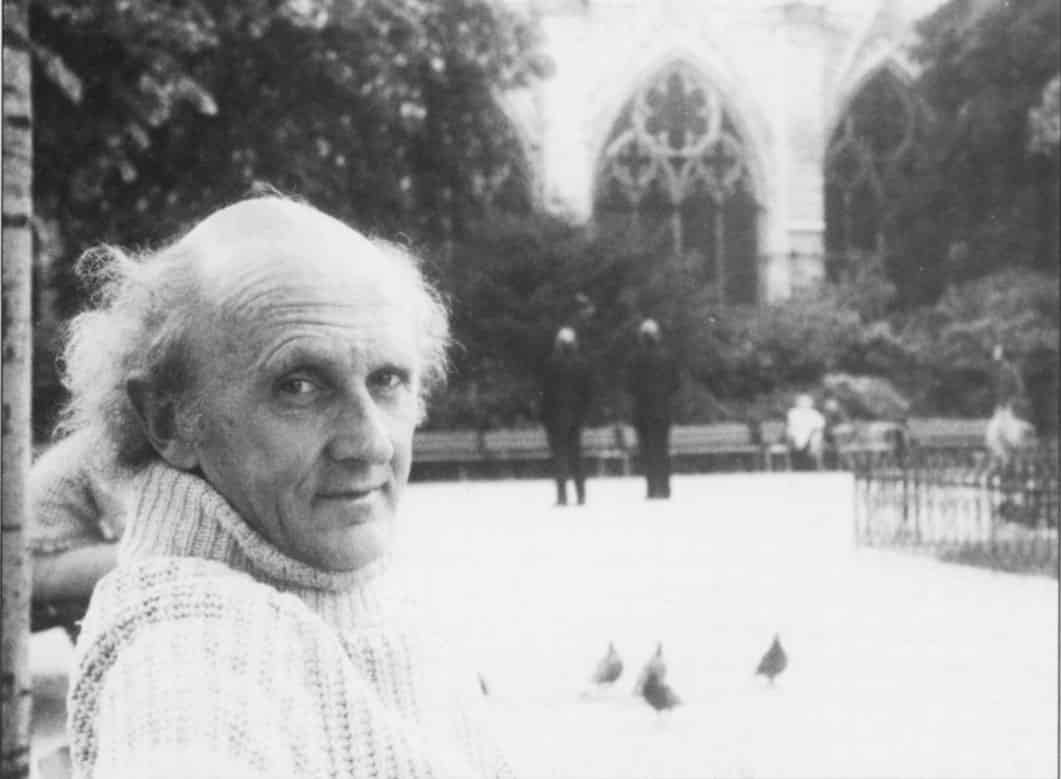

John Yule 30 years later with less hair but eyes undimmed - Paris 1975

John Yule 30 years later with less hair but eyes undimmed - Paris 1975Photo: Courtesy Pauline Carrol, State Library of Victoria

I obtained the services of an honest carpenter, and we dug the stumpholes and erected the stumps and bearers. He then got sick and had to leave us. It was some time before we got another starter. Undaunted, we decided to build the stone chimney ourselves. John Yule volunteered for the work and so did David Boyd, the painter and younger brother of Arthur Boyd. Motor vehicles were still a rarity in 1946 and generally changed hands at illegal black-market prices. However, we obtained an ancient 1924 Chevrolet utility for our building activities and in so doing felt we were giving ourselves a more professional look. John and David set off in the ute in high spirits the first day, and I accompanied them to the site with several hand-drawn diagrams to show them how it should all come together. I was ahead of this part of the work at the night classes and felt supreme confidence that the work would be performed in a tradesmanlike manner. David Boyd was to lay the stone and John Yule would act as labourer. David was a dark, handsome, Byronic figure with a deep, resonant voice. No one could fail to be impressed as he spoke about the kilns he had built for the Arthur Merrick Boyd Potteries. He understood all the intricacies of drafts and flues for this highly-skilled operation, and there had to be truth in his claim since the pottery was functioning at that very moment.

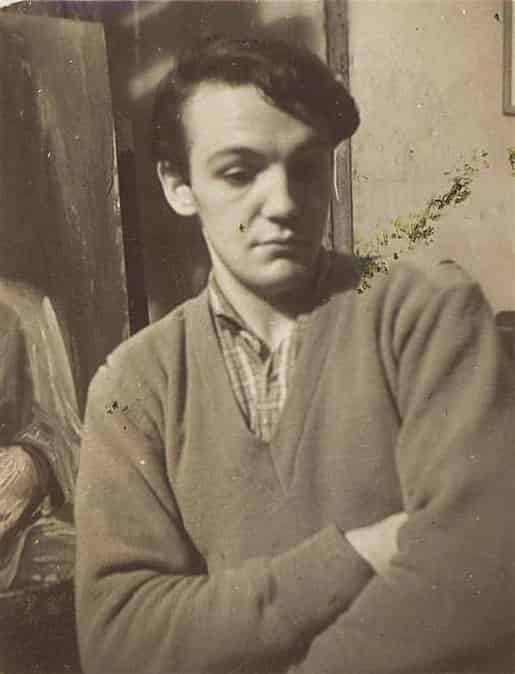

David Boyd in the early 1940s

David Boyd in the early 1940sPhoto: Albert Tucker. State Library of Victoria

When my bus arrived to transport me to the bank, I left David and John with a heavy heart. As the old green Leyland private bus wended its way into the cutting, I looked back to catch a final glimpse of the men I felt were gainfully employed while I would soon be imprisoned within the weary confines of the bank. I vowed that my situation would soon change, and it was with tremendous enthusiasm that I jumped off the bus in the afternoon and ran to see what progress had been made on the building. During the day I had tried to envisage how quickly David would work, in view of his experience with pottery kilns; but the view that met my eyes surpassed any hope either good or bad that I could have conceived. There were three or four stones cemented into two small heaps bearing no resemblance to the beginning of the chimney in any way except that they were in the approximate location it was to occupy. I tried to speak quietly to David, but I could not conceal my disappointment that he could be of no assistance in that sort of work. When I said I would have to start again, he remarked, with the slightest hint of condescension, 'Rather formal, don't you think?' But I didn't think that at all; instead, I made a decision to start on it myself in the weekend. There were some low stone retaining walls that could be proceeded with, and John Yule continued on his own with these. His sense of verticality was not all it might have been; but he did show an instinctive feeling for stone, and the result was both appropriate and aesthetic. I persevered with the solid-stone chimney and formed the inner hearth and the self-supporting arch over it. My work was at the other extreme to David's. It may have been a little too formal, but there was no mistaking that it was what it purported to be: a stone fireplace lined with slip-jointed fireclay bricks, in the approved institute manner.

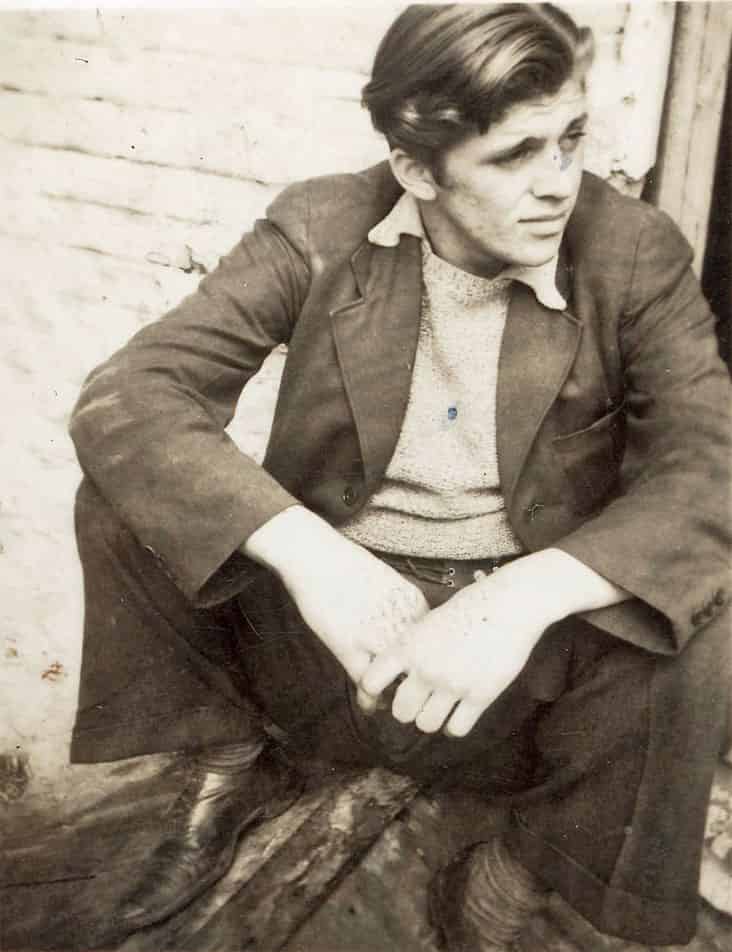

Matcham Skipper circa 1945

Matcham Skipper circa 1945Photo: Albert Tucker. State Library of Victoria

I finally found another carpenter named Laurie Mayfield, who in competent fashion took over the framing and general work, and I persuaded Macham Skipper to undertake the completion of the stone chimney, which was to be nearly five metres high and three metres wide. Matcham followed the ideas I had about the use of the stone we had, which was unruly in nature and hard to knap into disciplined spalls, though it possessed excellent spirit and character. While Matcham with his Montsalvat experience thought the material too brash, he realised that any further refinement would be almost impossible. He would climb onto the scaffold, all the while singing home-spun versions of operatic arias as though the whole manoeuvre should not to be taken too seriously; and then he would disappear, once night had descended on the work like a theatrical curtain. But he did finally complete it, and no one has ever criticised it since. On some occasions during its progress, Matcham would attack a bit here and there with a large hammer, trying to achieve a character nearer to his heart's desire - and have a 'go' at me at the same time. When an extension was made to the house a quarter of a century later, the stonework was found to be a foot wider at the bottom than at the top, but that failed to alter our good opinion of it. Everyone who knew anything about stonework agreed that John Yule's was the best job, but that he had also had the best of the stone. The house was practically completed during October except for some flash-panel internal doors, for which there was a delay of six months. I overcame this dilemma by nailing three twelve-inch-wide oregon planks lapped one and one-half inches, just as Burley Griffin had done to his own house across the road. The timber was too green for this idea to last, except as a temporary expedient, but the Brynings, who were by this time married, moved in to sounds of unlimited felicity. The only problem was that prices had doubled during the building operation, and we were glad to recover what it cost us without seeking the profit our cost-plus contract provided for.