Gordon Ford

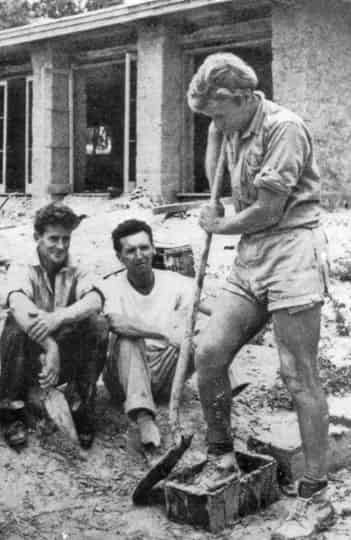

Gordon Ford, ably assisted by Alistair Knox and Tony Jackson, making mud bricks on an early Alistair Knox house

Gordon Ford, ably assisted by Alistair Knox and Tony Jackson, making mud bricks on an early Alistair Knox house

Landscape designer 1918 - 1999

We used to call him Thatch or Golden Boy because of his hair; and since he always worked out of doors he was tanned the year round. He eschewed matters of a material nature and this included the wearing of clothes - although he was happy in his tennis whites. It was comical to see him dressing for a formal occasion.

Gordon Craig Ford, who has died aged 81, was a man who spoke with his hands. He created beauty out of nature's most basic elements - earth, stone, water and vegetation. I first met him in 1939 when I worked in insurance and he with the Victorian Forestry Commission, which is where he learned so much about Australian plants.

The artist Peter Glass was also in insurance and my brother Roger was a draughtsman. The four of us were iconoclasts and full of fun. Our after-work haunts were the old Edwardian Treasury Hotel, the bohemian Swanston Family and the Mitre Tavern.

We threw ourselves into making mudbrick houses, and no-one worked harder than Ford. Later on, I asked how he introduced massive boulders into his gardens: "Gravity, mate, bloody gravity".

After a hard day in mud we'd beat it to the Eltham pub to drink with the Jorgensen mob from Montsalvat and there would be much shouting and laughter.

Ford was larger than life. He possessed a sharp intellect; he was passionate yet full of fun. He didn't suffer fools gladly but he was too polite to put them down, so instead would turn the situation into a joke and he always used this device to expunge any trivia.

He loved dancing to jazz but this was no normal activity, as his partners learned to their peril. His gyrations left the partner up one end of the room while he swirled and jived in a trance-like solo.

As the wildness of his youth gave way, Ford made a name for himself as one of Australia's great landscape designers. He'll live in his gardens, his resonant voice echoing from every boulder, every mudbrick, every shrub he so lovingly put in place. His waterfalls will sing his song of love and compassion. Graeme Bell Gordon Ford's funeral was held in the great hall of Montsalvat in Melbourne's Eltham. The grandeur of the setting was concomitant to the stature of the man.

Ford was the son of a Presbyterian minister and a teacher, both parents imbuing him with a reverence for learning. His first home was the manse at Haberfield, then open country west of Sydney, where, as a toddler, he loved the stands of casuarinas, those ancient Australian plants.

His father then was posted to rural parishes in Victoria; young Ford, an only child, spent all of his free time in the bush.

At 15 he was sent as a boarder to Scotch College, and then he undertook an arts degree, majoring in philosophy, at Melbourne University. Although essentially a pacifist, he joined the university regiment and when war broke out was sent to New Guinea on a non-combative posting.

On his return to Australia, he bought land at rural Eltham, trained with Ellis Stones and began his career as a landscape designer of rare distinction. Ford loved Australian flora with passionate fervour at a time it was decidedly unpopular with the average gardener, yet he was never a cranky purist who despised exotics. He believed water to be an essential ingredient in the Australian garden and loved constructing waterfalls and lakes.

He did major institutional work - Monash University and countless industrial sites - yet designing for the archetypal quarter-acre block gave him most satisfaction.

Ford suffered prostate cancer and died at home surrounded by family and friends. He is survived by Gwen, his wife of 28 years, and his children, Angela, Ben, Emma, Dailan and Caitlin

Phillip Jones, Obituary, Sydney Morning Herald, Friday July 2, 1999