A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 1: I am born

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 1: I am born

Author: Alistair Knox

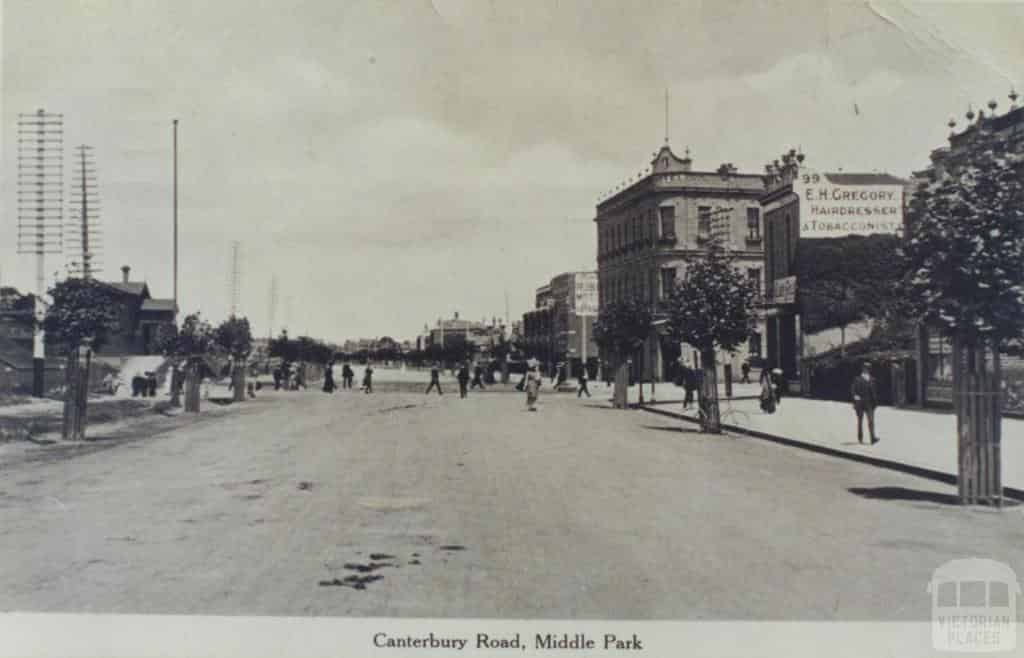

Apart from the sounds and tensions normally associated with childbirth in A.D. 1912, my entry into the world on Easter Monday - 8 April of that year - was without any remarkable incident. The street in which I was destined to live for the first twelve years of my life was both wide and straight, and it reflected the character of the community. It was the nearest road running parallel to the Beaconsfield or Marine Parade, which curved around the northern side of Hobsons Bay. The previous day had seen the first heavy autumn rains. The dry of the summer months was quenched, and an almost imperceptible smell of green growth silently pervaded the unconscious mind. The rain had washed the dust off the yellowing leaves of the plane trees that lined the wide streets, and the cobbled gutters sparkled with satisfying well-being. There were neither the lightnings nor thunderbolts nor other atmospheric convulsions which Shakespeare so often associated with the birth and death of the great. The family physician, Dr Johnson, attended the delivery at the appropriate time in his well-mannered horse and neat jinker.

Most births took place in private homes in those days, so the Sweeneys, the Campbells, the Williamses, and the Rosenthals - who were our immediate neighbours - were helpful and encouraging as they went about their daily tasks. The wives provided the qualities of good housekeeping while their husbands travelled to the City of Melbourne, three miles away, to their appointed positions in the marketplace.

Middle Park lies between South Melbourne Beach and St Kilda Beach and fronts onto Hobsons Bay immediately opposite the Williamstown Beach, on the farther side of those waters which together form the northern tip of the much larger Port Phillip Bay. A portion of the vessels that berthed there in 1912 were still square-rigged sailing ships. Their masts stood out sharp and tall in the evening sun as it sank behind them, and their yards were tilted at a wide variety of odd angles which expressed a sense of the previous century - when everything had been hand-made and individual.

The most fortunate thing that can happen to anyone on his arrival in this world is to be born into a family suited to his nature and character. I was doubly blessed in this respect. Both my father and my mother were intelligent and well suited to one another. They lived together in remarkable harmony and good humour. The tenor of their ways was not greatly troubled by crises. They had sufficient money week by week, and even if my father were to have fallen ill, he would have received his salary - but this was, at that time, the exception rather than the rule because my father was never sick and was in fact so conscientious that he never took annual leave, either. For this reason, my safe arrival on Easter Monday must have been an exhilarating experience for him. Public holidays were the only days in the entire year on which he was truly free from responsibility. They prompted him to rise earlier than usual and give my mother, my sister, and me breakfast in bed. It was always the same diet: cups of tea, and buttered toast cut into thin strips called 'ladies' fingers'. On his way back to the kitchen after delivering these delicacies, his jubilation would often get out of hand and he would clap and rub his hands furiously together in well-being and perform a kind of gambolling canter, shouting out 'Hey for the high jumper!'

We lived in a single-fronted house on a seventeen-foot frontage. The art nouveau lead-lighted entry door led into a passage which opened onto my parents' bedroom in the front, then my sister Isabel's, then mine, and finally arrived at the dining room, through which access was made to the kitchen, with the bathroom adjacent. The washhouse and the WC opened onto the backyard, which made up for its narrowness by being very long.

An Edwardian Middle Park house. Photo: Greg Hocking

An Edwardian Middle Park house. Photo: Greg Hocking

Both of my parents sprang from deeply religious evangelicalbackgrounds, and they were as fully persuaded of the same spiritual convictions as their own parents had been. They believed unreservedly that the Bible was - from cover to cover - the Word of God, and they had me circumcised on the eighth day, in the Jewish tradition. It was not that they were adding Mosaic Law to the spiritual grace they enjoyed; rather, they thought it a sensible practice to follow because they believed that some ancient laws could be of value to one's daily well-being apart from any spiritual significance they might have. They were convinced that God was in comprehensive control of the universe, so they aimed to obey Him comprehensively as well. The doctor must also have understood the situation, for he did do a creative sculptural job with the circumcision - it would have been approved in even the most conservative rabbinical quarters.

Because Melbourne was founded as late as 1834, its planning had been done in an era when wide streets and open spaces were preferred - a reaction against the degraded conditions which had followed the Industrial Revolution in Britain. Melbourne was not going to be another city like the industrial cities of England, where raw sewage ran down the lanes between workers' houses which were crammed back to back.

Melbourne's roads were of a generous grid pattern laid over the natural radial design formed by the Yarra River and its tributaries. A series of very wide stock routes which followed, in general, the radial design of the underlying landscape included Royal Parade, Dandenong Road, Bridge Street, and several others. Most of the roads suddenly reduced to a third of their width once they reached the farmlands (about two miles from the city centre) and, consequently, formed bottlenecks which have troubled the great village-city ever since. Unlike in Sydney, where so many narrow winding city streets originated as bullock tracks that wound through sandstone outcrops down to the harbour, Melbourne's landscape was a wide expanse of slightly undulating land shapes which were easy to exploit at will. Surveyor Hoddle's grand plan had conceived St Kilda by the Sea as a separate village reached by St Kilda Road, which would pass Albert Park on the south and Fawkner Park on the north to form a green belt between those open spaces - somewhat in the manner in which Colonel Light designed that green, concentric circle that was to divide Adelaide City from its suburbs a little later.

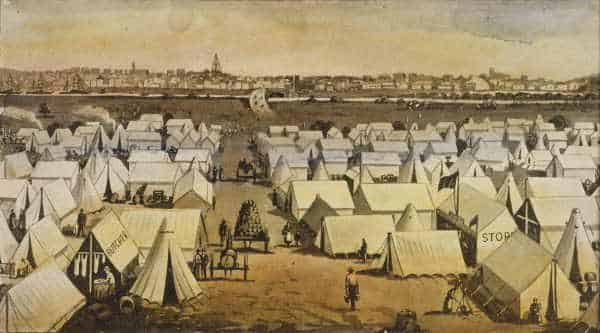

"Canvas Town", South Melbourne in the 1850s. Temporary accommodation for the thousands who poured into Melbourne each week during the gold rush

"Canvas Town", South Melbourne in the 1850s. Temporary accommodation for the thousands who poured into Melbourne each week during the gold rush

One of the first residential movements in Melbourne took place on a low hill, to the south of the city. It was originally called Canvas Town simply because the dwellings were made largely of canvas. It later enjoyed the beautiful name Emerald Hill. In a moment of unforgivable aesthetic dereliction - or was it through some hypothetical argument between the Orange and the Green? - the name degenerated into 'South Melbourne'. A third possibility is that it was an estate-agent's play to indicate its relationship to the city which so thrived following the Gold Rush of 1851, when the State of Victoria became the richest colony in the world. Whatever was lost in its name, however, remained in its generous streetscapes as it developed - especially in the St Vincent Place and Howe Crescent areas. To the present day, St Vincent Place is divided into north and south, with a garden hundreds of feet wide between. Howe Crescent, which forms the northern end of this generous design, seems - in some parts - almost as grand. Albert Park, immediately to the southeast, was more than a square mile in area; and the narrow wedge of land between Canterbury Road - which constituted the park's southern boundary and extended to the Marine Parade along the water's edge of Hobsons Bay - formed the southern extremity of the City of South Melbourne and was called Middle Park. The road system in this part of the municipality comprised as much as sixty percent of the total land space!

From my early childhood on, this liberality of street space kept the generally small pieces of land the individual houses occupied from conveying any sense of meanness or poverty. Instead, a relaxed, natural spaciousness - something the twentieth-century suburb has lacked - was created. The ubiquitous motor car has forced modern planners into the widening of main thoroughfares and the narrowing of residential streets for privacy and safety. One hundred years ago the street - in addition to the house - was the place where life was lived. And nowhere was this idea to be preserved in such a classical and generous style as in South Melbourne and its appendices: Albert Park and Middle Park.

As an instinctive understanding of my environment emerged, I had the sense of belonging to a community rather than merely dwelling in an isolated house. My mother used to wheel me in my pram along our front street just to show me off. She was inordinately proud of me because I was her only son and because I had blonde, curly hair which she thought was very pretty. One of our neighbours - the Russells - was the richest family in the street; their land holding appeared to comprise at least ten standard blocks. They had a very large grey dog with black spots who used to accompany my perambulations and place his head in the pram, close to my face. The keeping of dogs as pets was not common in those days because they represented additional mouths to feed - especially the larger breeds, which were rather the prerogative of the rich. I cannot recall this experience personally, but it has been well vouched for. My mother's personal style and general modesty mixed well together, and she saw this magnificent dog as providing a sort of kudos to her; this pleased her. The celebrated writer Compton MacKenzie could recall his nanny looking down on him in his pram when he was only six months old. My own recollection of events before the age of two years is generally very hazy except for one or two positive incidents, each of which I think particularly impressed themselves on me because I was being treated as though I could not possibly have understood what was being said about me. The first event involved my uncle Bob, a bachelor cousin of my mother's, who boarded with us and who had built himself a sleep-out ('bungalow) in our long, narrow backyard after my birth had displaced him from an internal bedroom. He was a Scotsman, with pure-blue eyes and a comforting Caledonian brogue, and I was deeply attached to him. He had gone to sea at the age of fourteen as an apprentice on a sailing ship and had sailed around the world three times before age twenty. He obtained his Master's Certificate at the age of twenty-one and sailed as first officer, in both sail and steam, to many romantic places; at the age of thirty-seven he retired from this occupation and bought a Newsagency in the nearby Melbourne suburb of Elsternwick. Uncle Bob represented adventure to me. Even at my early age the sea, and the ships I saw so often from where I lived, were something of an obsession. Just before my second birthday, Uncle Bob was booked on T.SS Benalla. He was returning to Scotland to see his aunt, who lived on the farm where he had grown up, just outside the town of Stirling on the field of Bannockburn - where Robert the Bruce defeated Edward II to liberate his countrymen from the Saxons some hundreds of years earlier.

I had been so securely nurtured at home that Uncle Bob's departure would be the first time I was to suffer a feeling of loss. I was looking forward to our separation with a mixture of regret and interest - regret because he was leaving for a long period, and interest because I was going to board the ship and then later watch it depart. Being the only son of a rather doting mother did have its drawbacks as well as its advantages. It created high expectations within me. I came to anticipate the best in every situation and would resort to manipulative measures were it not forthcoming. I am still amazed at how easily this scheming came to me. On the occasion of Uncle Bob's departure, we all travelled by train from Middle Park to Port Melbourne; when we reached the beach front, we could see the Benalla alongside the Town Pier half a mile away. The light cloud of smoke that rose from the ship's two yellow funnels made it appear she was anxious to be on her way; for me, this added great excitement and colour to the scene. My father suggested that we take the taxi which stood so conveniently nearby; but my mother, her sister Isa, and Isa's husband Jim Forman, together with Uncle Bob, said this would be an unnecessary expense, that we should walk the rest of the way. I knew this meant that I was going to miss my first chance to ride in a motor car, and I wasn't giving up without a protest. As we started to move I indicated that I felt sick, that my head hurt, and then I began to cry from frustrated desire. At this stage of my life, my mother was used to carrying my white cotton hat in her hand - instead of putting it on my head - so that passers-by would not fail to notice my loose golden curls. I had discovered that if I complained of a sore head on a sunny day, she would immediately feel guilty and think I might have 'a touch of sunstroke' due to her own vanity about my appearance. The ruse had worked before, but on this occasion I found them all unmovable - my scheming had no effect at all. My father ended the denouement by picking me up in his arms and saying, 'I'll carry him'. I dearly loved riding on his shoulders but, because of my feigned illness on this occasion, I had to just hang limp and let him carry me in his arms - an additional indignity. It was a warm Melbourne autumn day, and by the time we reached the ship's side I had fallen asleep. As I awoke I was aware of dried tears and an occasional shuddering hiccough going through my body. We all went aboard the ship and examined the cabin Uncle Bob was to occupy until it was nearly time for departure; then it was announced that there would be a four-hour delay because of wharf trouble. I realised I would not be able see the ship or my uncle leave the pier at all, and I urgently pleaded that we should wait. I was grieved beyond measure when friendly Uncle Bob himself said that we mustn't dream of staying. He would give me a special send-off instead. This was agreed to as though I were unaware of what they were talking about, which only added to the already prodigious disappointment of the day. We left the ship and stood on the wharf while my uncle stepped up to the next deck and waved farewell to me. I clearly remember the bright new yellow gloves he held in his hand as he gestured. His happy smile and azure blue eyes only added to the sense of betrayal I felt as he called out, 'Goodbye, Al, goodbye!' How could adults think children were so gullible?

Victorian infantry embarking on HMAT Hororata (A20), at the Port Melbourne pier. At left is HMAT Orvieto. Photo: http://anzaccentenary.vic.gov.au/

Victorian infantry embarking on HMAT Hororata (A20), at the Port Melbourne pier. At left is HMAT Orvieto. Photo: http://anzaccentenary.vic.gov.au/

Another incident at about this time involved my aunt Edie, my mother's younger sister. She was still unmarried and yet managed to enjoy a secret social life, which would have been denied her had her devout father known of it. Edie was hearty in attitude and breezy in voice and spoke positively, if not always cleverly, on many subjects. I had gathered that Isa - my mother's elder sister who helped bring up the family after their mother died - did not approve of a considerable number of Edie's ideas and opinions. I was aware of this because she and my mother - Maggie - were always together and would talk incessantly on every conceivable topic, even in my presence. They both were oblivious of the fact that I understood nearly everything they said; I just played quietly with my model train, all the while listening intently as they chatted. I so seldom spoke - I was intensely involved with what was going on, after all - that at some times there arose a slight suspicion I might be somewhat retarded. On the occasion in question Edie, having blurted out something not intended for my tender ears, looked up to find me watching her. 'Do you think he understands us?' she asked her sisters sharply. 'Oh, no, how could he?' replied Isa confidently. But Edie wasn't so easily satisfied. She turned to me and said bluntly, 'Do you know what we are talking about?' I just stood my ground and remained mute, thoroughly amazed that adults didn't know what their own children thought. When everyone discovered some months later that I could speak fluently, my father laughed gently and called me 'Silent Sammie' - which was my second name. He seemed pleased with my sense of reserve and control.

It was just before Britain's declaration of war against Germany in August 1914 that I finally achieved my first ride in a motor car. I had to attend hospital for a minor operation on my nose. I was petrified by the whole affair, especially by the sight of the specialist, clad in white, surrounded by half a dozen white pariahs - he called them 'nurses' - as they handled instruments and laid me on the operating table. The theatre reeked of chloroform, heightening my apprehension. As the ether mask was prepared, the doctor asked me to open my mouth - which I refused to do. I relented after five minutes' haggling and saw the mask blot out my surroundings as I faded into unconsciousness. When I awoke only the doctor remained, and my parents were talking with him. Within a short while I was wrapped in a rug and taken to a City Motor Taxi of elegant design - it was trimmed in maroon leather and was an early Fiat of superb character - and I gazed out through its oval back window as we sped towards Middle Park. The remaining fumes of the anaesthetic worked to condense the whole event into a single indelible memory, fragments of which probably continue to affect some aspects of my conduct and thinking.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >