A Middle Class Man: An Autobiography, Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapters

Chapter 11: Social life during the depression

Chapter 13: Bohemian associations

Chapter 16: The Eaglemont house

Chapter 18: Discovering Montsalvat

Chapter 20: Training at the Williamstown Naval Base

Chapter 22: Sydney for the refit

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Chapter 24: Martindale Trading Company (No Liability)

Chapter 26: After the Martindale

Chapter 30: Open Country - the Boyds

Chapter 32: The first mud brick house

Chapter 33: Early mud brick houses

Chapter 34: Giving up the bank

Chapter 35: Christian reflections

Chapter 37: La Ronde Restaurant

Chapter 41: Sale of the York Street properties

Chapter 42: Mount Pleasant Road

Chapter 43: Landscape architecture

Chapter 23: Sailing up the east coast

Author: Alistair Knox

It was determined we should proceed up the coast without delay as our real time did not start until we reached Ladava, the Milne Bay base. We sailed between Fraser Island and the mainland and past Brisbane until we reached Gladstone. The sense of watching the land come up to us was a great inspiration. We went ashore, where we immediately started a tension between the local girls and boys. The boys regarded us as a threat to their female possessions. We went to a dance that night, but had to leave when we sensed an ominous antagonism; so we returned to the ship and set out for the open sea without delay. There is a sense of open-mindedness of life on the ocean that occurs in no other human activity. It is a feeling of instability in the midst of eternity, a balance between an unchanging flexibility amid total stability that is close to the experience of every living person. It simultaneously placates our anxieties and increases our uncertainties. It is nearly impossible to plan ahead. Life is always in the present. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof, of watching and sleeping without asking why. I found watch-keeping at night a poem of eternity. The wartime necessity that prohibited the wearing of lights at night added to the wonder and the mystery. I used to hope it would get darker and darker as I walked around the deck in the middle watch. When the false dawn would emerge before I went below, it always seemed lighter than when we took our orders at the start of the watch. The sense of security coupled with isolation promotes reliance on coping with the unexpected, and it enables us to see our position in a wider perspective.

The first occasion on which we decided to anchor overnight - we were approaching the Barrier Reef - produced the type of trauma that so commonly besets those who go down to the sea in small ships to their business in the great waters. We consulted the charts, which indicated a point off an island marked as an Admiralty Anchorage. When we located ourselves over the position marked, there was a current of about three knots pushing us in one direction and a pleasant breeze blowing from the quarter. I was directed to the engine room to handle the skipper's directions from the flying bridge. The remainder of the crew prepared to drop the anchor, for the first time, in a seaway. Commands were given, and I followed the indicator pointing to slow ahead, stop, slow astern. But instead of being told to close down the motors, I kept receiving new directions - half ahead, half astern, full ahead, full astern - in a strange, unpredictable sequence. It was clear that all was not right. For about ten minutes we backed and filled until in a final gesture of disgust, the command was issued to proceed at full speed. At almost the same moment I could hear the anchor cable running out at an unchecked speed. The impetus of the ship accelerated the process, and in no time the full length of cable had been expended. From the engine room it was impossible to know what was really going on. I was told to stay at my post for about half an hour until the signal came once more to go 'slow ahead', then 'slow astern'; this was followed by the rumbling of the anchor cable being let go once more, to find its home on the sea bed. The command 'Finished with engines' indicated we were finally safely at rest. When I reached the wheelhouse, I was confronted by five weary men who had been forced to wind up the winch by hand against the ship travelling at full speed. When they first released the brake to let the anchor go, the cable refused to budge. Every movement was rehearsed again, in the darkness, without result until the skipper lost his patience and decided to forget the whole procedure. It had been overlooked that a line attached to the ring of the anchor remained lashed to the rail. Don suddenly realised the mistake and released it, and with it went the anchor. The attempts to apply the brakes failed because they were wound the wrong way and had jammed. The rewinding of the winch became a foot-by-foot struggle by four men for twenty minutes while the skipper looked on from the flying bridge with grim satisfaction.

Eventually, peace and contrition were restored and each crew member took an hour's anchor watch while the others slept. I always registered the same sensation at finding myself the only person on board awake, with the fate of the ship and my mates entirely in my hands. It accents a spirit of destiny that in the ultimate makes us feel we are the only living thing in the universe. Morning light soon causes such gallant thoughts to vanish, though, as the smell of bacon grilling in the galley restores the reality of interdependence.

The Martindale had an extraordinary record of readiness for duty at all times. It was unequalled by any small ship we had ever heard of. Before we had been at sea for a week, the auxiliary motor that supplied our electricity failed. Undaunted, we jury-rigged the motor that had been placed on board only the day before we sailed - right on the deck, in a Heath Robinson manner, and supplied with occasional buckets of sea water for cooling so that we should not be hindered in our progress. Nevertheless it was essential that it finally be properly installed at Townsville, which we would reach in a few days. In the meantime, we went ashore at various uninhabited islands and even hunted wild goat for meat - with more damage to ourselves than to the quarry.

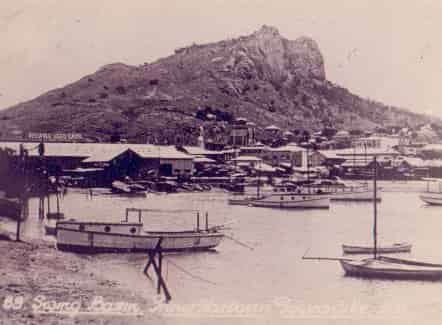

Swing Basin, Inner Harbour Townsville 1940s

Swing Basin, Inner Harbour Townsville 1940s

Townsville had become a focal point in the war - with its notable fights and rough play between the services, and also for its erratic beer supply. The pubs opened sporadically when barrels turned up and was dispensed from large enamel teapots instead of by the usual method. However, we were soon engrossed in weightier matters. We put our bow on a sandbank on the far side of Ross Creek, where we berthed and tried to fix the leak that had opened up on our first great night at sea. Don and I were struggling in the engine room to install our auxiliary motor by drilling through the steel deck to find a secure mounting and tapping into the main-motor water system for cooling. I went up to the Townsville depot and marched out in front of the quartermaster with a stolen length of two-inch piping that would form an exhaust pipe up through the funnel. After two days of fruitful work, we felt it was time for a little fun. Norm and I had decided to initiate the skipper into the democracy of the small ship, where everyone was equal. We arrived back on board at six in the evening to find the skipper on board alone, so we discussed where we should go to have a drink before we set off to the dance being held that night at the Bowling Club. The skipper said, 'Each of you give me two shillings and tuppence and we'll open a bottle of whisky'. We knew he had a crate bought out of bond for six shillings/and sixpence a bottle before we left Adelaide - which was very cheap in any man's language. He brought up two bottles instead of one, and some glasses, and we climbed over the deck of the corvette that lay between us and the jetty; then we set off for the social life. At the first laneway, we stopped to drink some of this hellfire. I poured out a whole glass and offered it to the skipper, who quite sensibly refused it; so I drank it off at a gulp and handed it back for Norm to do likewise. We knew the skipper would rise to the bait. He would always do anything he was challenged to do. So he drank a full glass, too. I immediately drank a second glass; in less than five minutes, we were all dizzy with alcohol. The skipper was more juvenile than we were because he suddenly realised that he could throw away his dignity and take charge through fraternal methods. We drank some more on our way to the Bowling Green until we could see it in the distance in the evening light. The crowd were all keeping to a straight path that later turned at right-angles, so I set off across the undergrowth diagonally, in my inebriated condition, with the skipper's arm around my shoulder as he swore eternal friendship. Without warning I stepped into a drain two metres deep that had a thick layer of mud on the bottom. My free-flight descent came to a jarring halt as my knee struck my jaw and smashed two teeth. The skipper still had his arm around my shoulder as he landed on top of me. In a stunned stupor and covered with mud and slime, I started to clambour up the other side of the open drain as if nothing had happened.

Sailors dancing during the war

Sailors dancing during the war

When we finally walked up the outside wooden stairway, a policeman said that I would not be allowed in - which by this time rather suited my debauched condition - so I started to go down the stairs again. He also told the skipper he couldn't get in either, at which statement the skipper leapt at his throat, trying to strangle him. Norm grabbed the skipper from behind, which caused him to turn on his protector - who was a step lower - and push him bodily downstairs with his foot. I saw the malevolent light in Norm's eye as I lay spreadeagled on the landing, and I quickly estimated that the skipper's hope of a long life was momentarily in jeopardy. All this time, respectable soldiers and sailors from the Australian and U.S. forces, accompanied by their girlfriends, were pushing past us to gain access to the entertainment. At that moment, the remaining members of our crew arrived and stopped a major confrontation between the skipper and the law. I had only one aim left in life: to lie down and sleep. I found a spot in some long grass and faded into oblivion. I was awakened by the starting of cars and trucks as the dance finished and the participants made their way home. The crew members were wondering what to do about me when they suddenly caught sight of my dishevelled figure as I dodged between car lights coming past me from all directions. Norm came after me and rescued me, and we set off for the bus. I imagined I was quite sober once more and insisted that we board a bus going in the opposite direction to our destination. At the terminus we were informed it was the last bus; that left us with the alternative of sleeping where we were, or walking back. I felt as though we were halfway across the Atherton Tablelands. Norm was a great mate. He put up with nonsense and talked of how the skipper had finally gotten into the dance by promising to sit down and behave himself. In the end he even danced himself, but no one knew whether or not his partner ever recovered from the ordeal. We were eventually picked up by some soldiers in a van and dropped off at the Ross Creek jetty. All was dark and silent on board the corvette that lay between us and the pier. We silently slipped across her deck to reach the Martindale. To our amazement, every light was blazing. It was as if a ball were still in progress. We entered the wheel house, which led down to the stateroom. At the doorway I thought for a moment that I was looking at the decapitated head of the skipper, beaded with sweat and eyes closed in agony. The next moment revealed that he was hanging over George's shoulder and that they were locked in a great struggle. George was trying to get him to bed, but he still wanted to play. All of a sudden he released his grip, rushed across to the small open porthole to vomit, and then immediately returned to the struggle without spilling a drop of vomit in the ship. We went out and left them to it. A little while later we could hear George saying, 'Port leg in here, starboard left there', and we knew that wise counsel was tactfully directing our worthy commander towards a well-earned rest.

As the dawn began to make its presence felt, the remainder of us gathered in the Saloon to review the highlights of the night. We had all become calmer and wiser. Norm fell quiet for a few minutes, and then started to look at me. Suddenly it struck him what a hopeless fool I had been. He immediately charged and pushed my head into the sink as if he intended to push me down the drain. My legs were up in the air as I lay helpless under this well-justified onslaught. Exhaustion finally caused him to stop and I quietly eased myself up, glad that I had got off lightly. We never went to bed; we just stayed around like drug addicts meditating between fixes. The skipper appeared, correctly clothed and in his right mind, at about 10 a.m. The depredations of the past sixteen hours had left him with a pink complexion, bloodshot eyes, and a guilty look as he tried to calculate who had seen him at the dance. 'Pat, will you please row me across to the jetty? I have to go ashore', he asked. Pat obliged and put him onto a ladder up which he could climb to the deck of the jetty. The one thing the skipper hoped was that he would not be recognised by any officer of any service who had seen him the night before. The counter of a small American ship overhung the ladder until he was halfway and came within sight of the commanding officer leaning over the rail. As soon as the officer saw him he said, 'Ah! The Bad Man from the Bowling Green!' The skipper nearly fell back into the dinghy, but retained just enough poise to carry on. The crew had great hopes for a democratic future, and for a few days it looked as though it were possible.

As we entered Cairns, bad weather closed in and remained for a week as a cyclone passed over us. We were prevented from leaving our last Australian port from day to day as swirling mists engulfed the town. We also heard that HMAS Metefeli, a ship about twice our size, had been lost with all hands. Occasionally we had mistakenly received letters destined for the Metefeli, so that we shared a mutual comradeship because of our related itineraries; it made her loss a very personal one for us, although we had never seen either her or her crew.

Just before we left Cairns, a leading seaman was drafted on board, consigned for our destination in Milne Bay, and we were also given orders to tow some landing barges out to the Flinders Reef to refloat a ship that had gone aground. The seas were still rough when we set out before daylight. We had all been indulging at the canteen the night before, and I found my stomach at war with itself as I watched our tows almost standing on their ends in the seaway. When the skipper signalled the shore base to report progress, finishing with the phrase 'All ships comfortable', I felt it was the most erroneous statement of the month. We slipped our tows as we approached the ground ship and set off across the Arafura Sea direct for Milne Bay. Our draftee had spent a lot of time at sea on naval ships that were much larger than we were. His introduction to real 'sea time' revealed weaknesses he never knew he had. We dipped the rail every roll the whole way across, and he just lay in the wheelhouse groaning helplessly with seasickness. The only sustenance he could stomach for four days was the special Kai I made, usually to be consumed during the change of the night watches. It consisted of equal parts of cocoa, sugar, and unsweetened condensed milk and was of the consistency of heated honey. It fell into the mugs in large globules rather than as a fluid. When our passenger sipped this nectar, he intoned 'Good Kai, Knoxie' between sips, and kept on after he had finished it and was sinking back into a coma. The sea was dotted with tree trunks, coconuts, and other remains of the fury of the cyclone. On the fourth day we made landfall, which is the thrill every navigator has experienced since time began, no matter how often he does it.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >