Alternative Housing, Lord Deliver Us from Experts

Lord Deliver Us from Experts

Author: Alistair Knox

Survival in a dismal economy

Tomorrow? Why tomorrow I may be

Myself with yesterday's sev'n thousand years.

IT would be beyond comprehension that we could spend so much time considering 'tomorrow' if it were not for the fact that we are destined for immortality, no matter how certain we are of our physical death. Only the most. hardened materialist would deny the concept that every one of us can make innumerable moral decisions day by day which also carry responsibilities that must eventually be faced. Privilege and responsibility are equal and opposite aspects of the same truth, and can only be properly considered after the end of our earthly lives.

In our immediate past the Australian work ethic tended to be equated with worldly success. The wealthy regularly attended church on Sunday, no matter what they thought in private or did in public on Monday. Those whom they employed at the lowest possible wages joined them on Sunday to sing 'God made them high and lowly and ordered their estate'.

But today the democracies of the West, despite their great power and wealth, are being deeply threatened by the business and manufacturing competition of the East and its low-cost, hardworking, teeming millions. They are the labour resource of multinational corporations which originate in the rich democracies, and which direct the commercial and trading interests of the free world into fewer and fewer hands.

These impersonal juggernauts, powerful largely because of geographic location and historic circumstance, are not concerned with moral values as they ride over the integrity of individual nations. Their computers are bereft of spiritual values and their prospectuses devoid of the concept of 'sin and salvation', the mainspring of man's deepest needs and hopes.

The 1977 Australian general election introduced new factors into our society. It was argued by political commentators at the time that unemployment was the most pressing issue of the election. The results made it equally clear that the new 'workless' class, artificially created to meet the needs of international and national business conglomerates, was of no concern to either employers or employees. Life was not meant to be easy for the displaced or the dispossessed. The ethics of surplus labour had become the new law of the commercial jungle. A 'formula' had been implemented to take away any sense of personal responsibility that might affect sensitive consciences. By claiming that there was plenty of work about and that only those who did not want to work were affected, government leaders could ignore the thousands who regularly apply for work and do not get it. The reasons frequently given are that young job applicants don't dress properly for interviews, are dirty or have long hair, are illiterate or do not give sufficient evidence of belonging to the worn-out conventions of yesterday's middle-class. (Mind you, it is also apparent some young people have unrealistically high expectations of their own value as novice recruits to business organisations.) But the young unemployed cannot be held responsible for the debilitating effects of a depressed national economy.

The unemployment problem came to the Eltham district a little later than most other areas, partly because a fair percentage of the population had been self-employed in mud-brick building and other environmental projects. The local government had also developed a 'Drop-in Centre' for the increasing number of unemployed teenagers, but it soon became evident that its objective of providing amenities and social exchange among the increasing percentage of its younger population did not eventuate as anticipated. It became a pick-up joint for drinking teenagers at night and an extension of the Commonwealth Employment Bureau by day. The latter was so singularly unsuccessful in its program that its name was changed by those who used it to the 'unemployment bureau'.

An experiment in communal welfare

Our local church fellowship became involved in the Centre as a mission field in our own hometown. In order to communicate with the new workless class, we had to learn the 'language' that could be

understood by those regularly attending the Centre. We had to get to know them and to be concerned. We knew it was impossible to get jobs by scanning the Situations Vacant columns of the daily press, the current approach when we started. A revised attitude would be needed if employers were to be encouraged to take on new staff. Even if there were openings, they were reluctant to do so because of the high ancillary charges in employing others beyond the actual wages paid to them. By the time most potential candidates had applied for a dozen different jobs, they had become disheartened and felt useless. They suffered from unemployment shock, a disease unknown for over thirty years in our prosperous society.

The unemployment crisis was demonstrated in a number of ways. First was a resistance to the consumerism that had gone on unabated since World War II. Secondly was the movement towards zero population growth, which also prevented increased demand. Thirdly were the limitations of a nineteenth century economic outlook, which cynically disregarded the economic changes breaking around it. The fourth, and probably the most important factor, was the growth in power of the multinational corporations.

We examined methods of alternative employment which were based on self-employment and were community-oriented. As the district had strong environmental qualifications, we 'tooled up' for mud-brick making and building, landscape construction, vegetable growing, bread making, ironwork and forging, native plant propagation and nurseries, weaving and spinning ... to name some of the more obvious fields. We invited people to train in these activities, whilst warning them that in some callings they would receive less than if employed on an award basis. The obvious advantages were shorter travelling time to work, congenial activities, opportunities for self-development and membership in a community-oriented economy with which the big business could not compete.

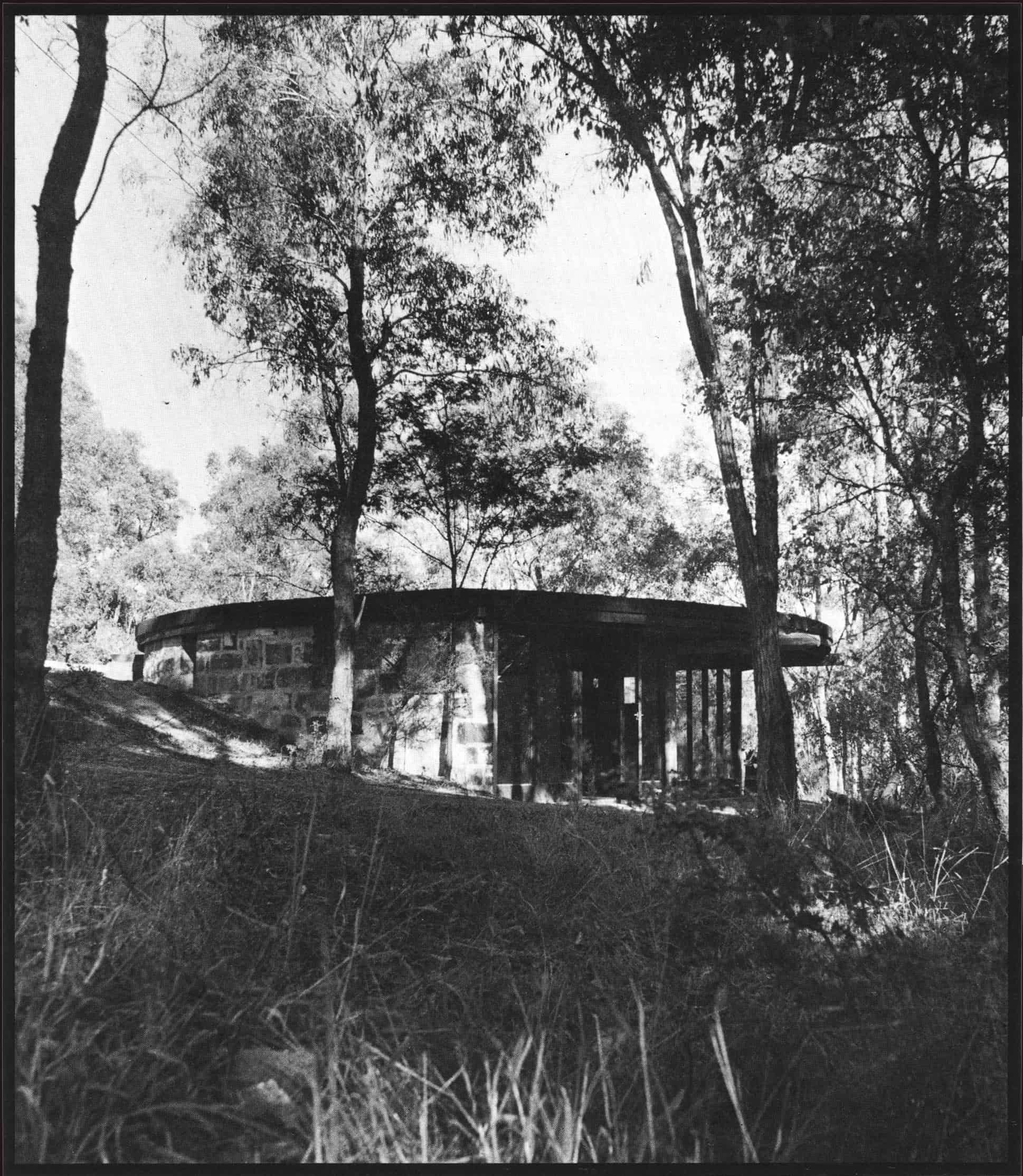

The Knox drawing office - an environmentally stimulating workplace

The Knox drawing office - an environmentally stimulating workplace

On a sunny, winter morning four men met around the big refectory table that dominates the centre of our bluestone-and-glass drawing office. This building has a strong environmental design character. A raised, square, central roof area is provided with clerestory lighting, and a skylight of forty square feet is set immediately above the table to permit full daylight to enter freely. This counters the effect of the solid stone wall on the south, buried five feet below the ground level.

The north side is a little above natural ground level and consists of more than a thirty foot run of full-length windows and glass doors that bring the natural bushland right into the inner spaces. The contrasting dark stone and the pellucid sunlight generate power and serenity. There are no divisions or private offices, except for a store room and toilet facilities, which form an alcove on the west side behind the large, open fire-place. The whole space has an open-planned, democratic climate. The urgency of work is always tempered with a sense of well-being, so that the philosophy of the whole man is allowed to blossom and grow.

On the morning in question, the three others seated at the table were Roy Johnston, one of Melbourne's best and most successful engineers, Andy Ralph, an Eltham Council social worker, and Robert Bakes, a delightful colourful ex-shearer, sporting a handlebar moustache. Robert had retired from school teaching to take on his shearing but, in the course of journeying around Australia, had come across our environmental activities and fallen in love with mud bricks. I remember asking him if it was easier to make mud bricks at forty cents a brick or shear sheep at fifty-six cents. He assured me that shearing was proportionately easier and he knew what mud-brick making was all about. He had evolved a one-man system capable of producing 300 bricks daily. To that time it was the best individual effort we had known. When I met him a year later, he informed me that he had a new method and that a day earlier he had made 1012 bricks on his own.

The reason for the conference was to arrange a demonstration to teach the unemployed about local district trades they needed to master to become self-employed. This was left to Rob Bakes. We also planned that other forms of work, such as spinning and weaving, could be sold at the local Opportunity Shop without retailing margins being added. We decided to approach the local council to lease an area of land on which a nursery could be established. The name of our game was survival through community improvisation.

At about this time I gave a series of lectures to an environmental studies group at the College of Advanced Education in Canberra, and to the architectural faculties at the Universities of Newcastle and New South Wales, Sydney. They were all well and enthusiastically attended and the fundamental issue they raised was that of 'learning by doing'. The imbalance between technical training and practical learning was very marked. At least half the students involved expressed an urgent desire to get on with some practical building. This was particularly apparent because of the large percentage of architectural profession then unemployed in Sydney. It was a gloomy situation.

It occurred to me that it would be an interesting experiment to invite as many students as possible from the universities to have a 'Build In' in Eltham during 1978. I suggested it be in August, which would coincide with the end of their second semester and the week of our Eltham Community Festival which we started the year I was Shire President. The program would include eight hours building each day, working on a big barn for distributing locally-produced foodstuff, which could further generate community interchange and barter. Bread ovens could also be built to create an Australian 'peasant' atmosphere. The evenings would be spent developing various activities to stimulate interest in an Australian-style community, as a contrast to the flagging political ideologies of both right and left. There could be few better places for an occasion seeking an answer to our present philosophical and social dilemmas.

In the actual event, many who wished to come were prevented by their study programmes. Those who did arrive had an experience they are not likely to forget for many years. Heavy periods of rain and mud reinforced the well-worn statement that 'no mud-brick maker likes the rain'. The opposition of nature hardened the resolve of both sexes as they caught something of the spirit of Leonardo Da Vinci's famous remark that 'God gives us all good things at the price of labour'. Some were experiencing the evaluative actions of the head, the heart and the hand for the first time.

Peter and Marion Huggett, owners of the land on which the barn was being erected, then took over in conjunction with my son Hamish. The building is at present three-quarters finished and it is anticipated that it could be in operation within a few months. It has combined sound proportions with primitive materials to form a structure that will be ideal for the sharing of natural foods, the practice of homeopathy and living a genuine community life - a prophetic encouragement that glimpses the way ahead for our existing society, baffled by the implications of the fossil fuel crisis and the dehumanising effects of the computer.

It is more than coincidental that this social experiment should take place within a mile of Montsalvat, the artist colony which embarked on a program of adventurous living more than forty years earlier in the midst of the Great Depression. That group of students retreated from a chaotic and poverty-striken suburban life to build a creative community. They combined stone, old timber, mud bricks and hand-made bricks to form a medieval French village, complete with baronial hall, towers, dormers, lofts and a bell tower. It is quite different from the rural-suburban society that now surrounds, but cannot overcome it. That society itself has to a large extent been won over to it. The scandalous overtones of its early days have given way to a full social acceptance. The rich now have their marriages solemnised in its bluestone chapel and the Governor dines in its Great Hall. Its founder, Justus Jorgensen, died in 1976, but his pupils still carry on as enthusiastically as ever.

It is an inspiring experience to watch Matcham Skipper and his son Marcus working together on one of their many Renaissance activities, such as casting enormous sculptings in the manner of Benvuto Cellini. They combine improvisation and tradition with intense vigour and belief.

Their aims differ from the barn building the students commenced. The Skippers formed a separate enclave in society, where the barn is for all people. This change reflects how far society has moved since the Depression and presages how much more of it will change in the future. There is as yet no shadow of a guillotine darkening the landscape of suburbia, but it is possible that as many heads will roll if not literally then metaphorically, and as many changes take place in our society in the next ten to twenty years as it did in the infamous French Revolution.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >