Alternative Housing, Designing for Cyclones

Designing for Cyclones

Author: Alistair Knox

The fusion of engineering with nature

In the cause of environmental design in building, landscape and survival, it is sometimes necessary in Australia to travel thousands of miles merely to cover the areas of study. Darwin is more than 2,000 miles from Melbourne, yet it is a part of the one, timeless continent. The same sort of people are doing the same sort of things. The same fawn-brown treeless landscapes extend for a thousand miles before they imperceptibly turn into burnt rose and black across the Tropic of Capricorn. As you fly for hour after hour the uninhabited plains, punctuated with sudden parallel ridges, roll towards you from the horizon like waves, then move past and disappear behind. The clear, blue sky and the intense sunlight occasionally grow hazy in smoke palls 100 miles long. A very rare river has water in it, but the whole land formation can be read in the dry river beds, defined by the concentrated tree growth along their waterless courses.

It was not until I returned from Europe three years ago that I became fully aware of the fundamental difference between the Northern Hemisphere countries and Australia. We landed in Darwin at 3 a.m. Two rather elegant officials, dressed in white shorts and shirts, entered the plane. They carried pressure packs which they solemnly squirted up and down the coat-rack storage space from one end to the other. Half-awake figures lay contorted and twisted in all directions. They watched this operation in bemused disbelief. The white shorts and shirts disappeared as methodically as they had come. Just as we were wondering whether it was a real or imaginary visitation, one of them cocked his head back into the great cabin for a moment. He looked up and down the aisles. 'It doesn't seem to have affected them much', he announced to no one in particular, without moving a muscle in his face. He then withdrew his head. Nearly every country has its national characteristic, but none is more laconic and spontaneous than Australia.

I had desperately boarded the plane at Hong Kong the previous afternoon with minutes to spare. Sweating copiously and suffering from claustrophobia and frustration, I should have missed it by hours, but the plane timetables throughout the world were out of order because of the short war which had just concluded between Greece and Turkey. It had isolated me in Jerusalem for a week longer than I intended to stay. It was a magical experience to be marooned in that landscape and country. The historical centrality of the fertile crescent, the original trade route between three continents, still retains its ancient charisma. This was especially true of the Judean hills and Jerusalem. The Old City, dominated by the tower of David and the Dome of the Rock, with the Mount of Olives rising up steeply beyond the Kidron Valley and Gethsemane, all shone with that piercingly clear white light reflected by the limestone formation. To the right, the road to Damascus wound over the saddle near Bethany. On the eastern horizon the hills of Jordan were shrouded in a permanent brown haze caused by evaporation in the Dead Sea, concealed from view by the intervening hills. The proximity of one country to another was forgotten in the place names and the unchanging stone-faced buildings of the city of the great king.

A mud brick idyll - Esther Rodenstock drives the tractor and Helen Hyatt wets the soil, while the author and the Rodenstock children supervise. The Woolshed Valley lies in the distance

A mud brick idyll - Esther Rodenstock drives the tractor and Helen Hyatt wets the soil, while the author and the Rodenstock children supervise. The Woolshed Valley lies in the distance

The five indigenous Australian elements: space, peace, colour, light and the antideluvian landscape

The five indigenous Australian elements: space, peace, colour, light and the antideluvian landscape

|

The sudden night change to Darwin was extreme. The struggle for breath that pervades cities like Hong Kong was gone. There was a deep silence and a velvet blackness as one stepped out of the plane. The two-storied customs building some distance away was built in the usual tradition of Australia's north. The first floor was supported by wooden columns, and the ground floor was partly open. The air smelt completely different from everywhere else because of the pervading scent of eucalypt and the great areas of unpaved earth. The building itself was well built, a practical timber construction without pretension which performed its functions with directness and without fuss. Despite the hour, the bar was open for those who believe that Foster's lager is essential to celebrate a native's return, and food was freely available. But I was more impressed by a polished, stainless steel cubical tank on the first floor about four feet all round, filled with ice cold water - clear, pure and delicious. Coming from Europe where so many taps are marked 'undrinkable', and the major liquid refreshment is bottled mineral water, this simple freedom of Australia touches an inner sense of gratitude. This experience of liberty increased as we flew into the morning to land in Melbourne about five hours later. The western suburbs are normally the most depressing part of the city, but on my return I did not even register their existence. I was fully occupied by five indigenous Australian elements. These were the sense of space, the sense of peace, the sense of red-gold colour and of light, and the sense of the antediluvian landscape - although at that time I could not even see it. Many seasoned Australian travellers say they always experience the same emotions. The real quality of Australia lies in its vast, untameable wilderness and desert, and survival-conscious flora. It was not by chance that the Creator placed the Australian land mass so that it divided the three great oceans of the world: the Pacific, the Indian and the Southern. It was to support an alternative environment and so had to be independent of all other land masses.

The City of Darwin in the wake of Cyclone Tracey

The City of Darwin in the wake of Cyclone Tracey

The question of the environmental future of these enormous spaces engrosses the mind as the aircraft glides over it as quickly as the indigenous nomads had been slow from the days of their genesis. Will the parched and uninhabitable sand dunes of the

Simpson Desert one day produce solar power and graduate into the most valuable real estate in the country? Are there other sources of life that are still to emerge from its womb like the seed of Abraham from his erstwhile aged and barren Sarah?

It is doubtful if such dubious considerations occupied David Freeman as he flew south to Melbourne recently to discuss ideas for his new house in Darwin. David had been a career engineer with a big construction firm, until the pressure of work caused him to withdraw from it and start up for himself in the grey, corrugated iron flatness of a thousand roofs of the northern capital.

The wreckage of Cyclone Tracy of Christmas 1974 had been generally cleared up, but in every street there was still a proportion of unroofed buildings, twisted structures on piles, half-stripped trees and devastated undergrowth which warned that better methods would be needed in the rebuilding that was now going on all over the city. David was rapidly establishing a reputation for practical hurricane-proof design, but he had had to admit to himself that his answers were not in keeping with the eternal characteristics of the landscape that carried his buildings. This was why he was visiting me. His engineering services were prompt and economic. His clients would be safe, but he himself remained uninspired and unfulfilled. The streams of his thinking were flowing into the more complex ocean of total planning. As yet the transition from the single to the multiple problem was still a series of separated thoughts. They did not move silently from the conscious to the subconscious. The individual streams, like different coloured liquids,· had yet to mingle together to become one complete new colour. The environmental concept is a total concept, because it reveals how mankind is couched within his boundaries. It is not something outside man but within him, and man himself is its most important element.

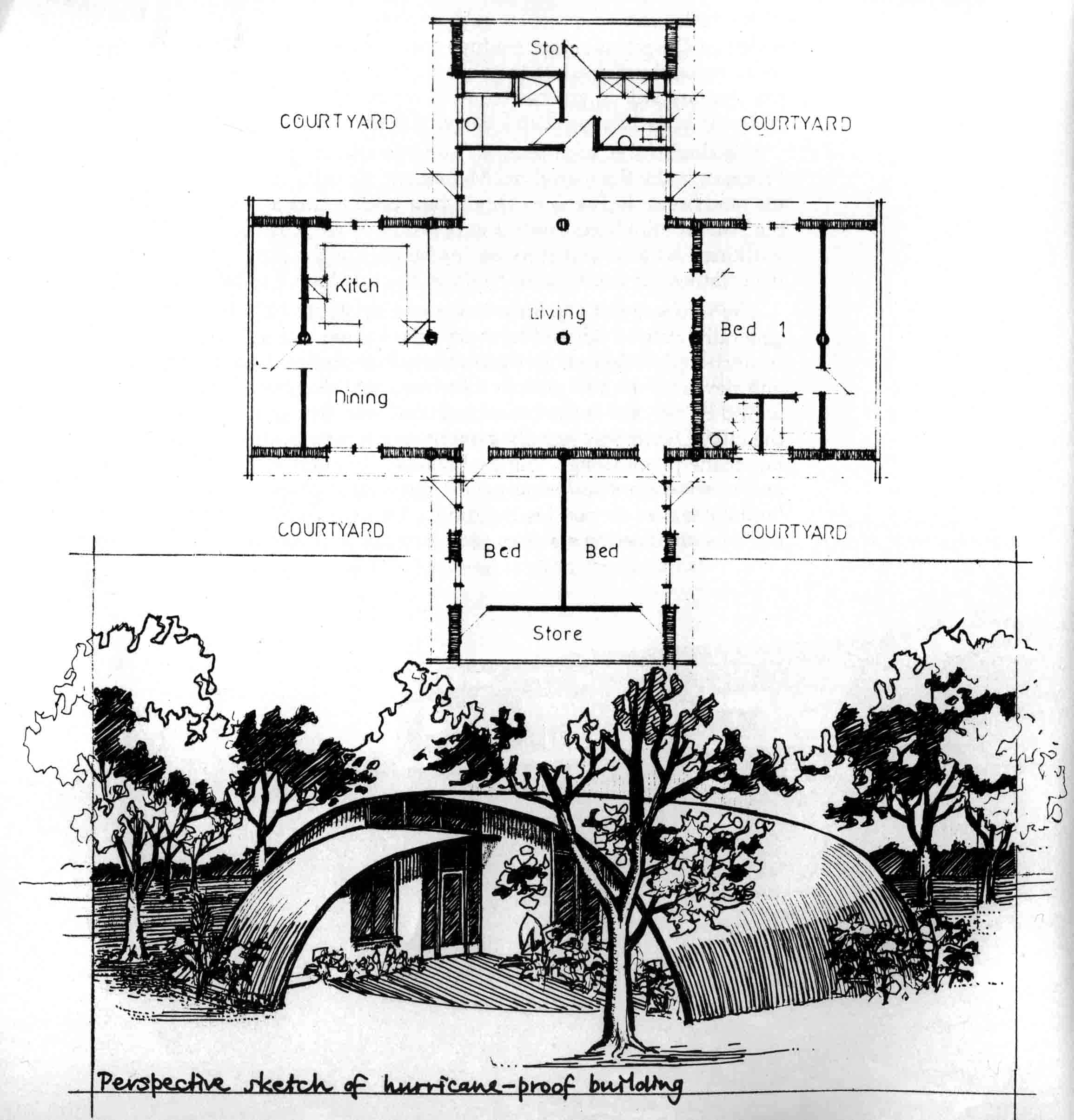

Plan of the Freeman house

Plan of the Freeman house

This visit to Darwin followed my first when I returned from overseas. There is a spirit of activity and life in the town, no matter what time you arrive. The airport is crowded with people and surrounded with cars which seem to be going off in all directions with purpose and energy.

It was the month of August, in the dry season and the coolest time of the year, but by two o'clock in the afternoon it is very hot and tropical, with a strongish wind blowing. It only takes minutes to change into shorts and sandals. The heat, like alcohol, is a great leveller of people. The population of over 40,000 is almost as large as it was before the cyclone which so severely damaged property and caused considerable loss of life. It is interesting, however, that only about half of the pre-cyclone population remain: the remainder are new residents. A sense of frontier-town restlessness and change pervades the atmosphere. There are many cars and the flat, wide pavements that give time and space for vehicular movement make the town seem outwardly calm. But underneath there is the latent fire of uninhibited noise and speed of a carefree, under-governed community. The police seem conspicuous by their absence. The urban structure is more an agglomerate of householders, with equal privileges and responsibilities, than a normal city of rich and poor living in separate suburbs with differing standards of living. The flatness of the landscape causes a high rise and fall in the tides, which can surge over the land in periods of cyclonic violence. The history of hurricanes creates and keeps alive in the minds of the inhabitants an abiding awareness of the power of the natural environment around them. They become very different citizens from those in the materialistic empire of the eastern suburbs of Melbourne, who cling to their possessions as if they believe they can save them from death itself.

David Freeman and his wife Robin have become fully-fledged Darwinians, with a stake in its future. They can be envied in many ways. There are great opportunities to develop Darwin's potential because it is the rail head for beef cattle, uranium and many other commodities. It is growing quickly, but it is still small enough to be personal. David had just gained a permanent lease over nine acres of property very near the centre of the town, and he and Robin were planning to build on it at once. A creek flowed across the bottom of the property, and some distance above its banks was defined the surge line. The area would produce a great garden and had excellent landscaping possibilities. The destructive winds cannot repress the rapid regrowth that occurs in the tropical conditions. Pawpaws become fruit-bearing trees in as little as six months. A wide variety of fruits and vegetables can be produced very simply because of the abundant water supply, both through nature and reticulation. David was busy designing his requirements into the landscape, which would include the growing of crops and the agistment of horses. The horse is still a significant animal in Darwin for recreation, and it is used 'down the track' on stations and farms in primary industry.

I examined the building systems which are appearing in new estates and on individual allotments. Most of them are practical and normal. Some of the mass productions have good points, but in total they are nearly as dreary as suburban Melbourne and Sydney, except that there are no paling fences. I find it hard to see why the land cannot be subdivided in a more interesting way and why, with a little replanning, the feeling of repetition ad nauseam could not be wiped out. A simple system of clusters would do marvels if it were added to a choice of design modules. Even a regrouping of two houses forward on the land and two back would help.

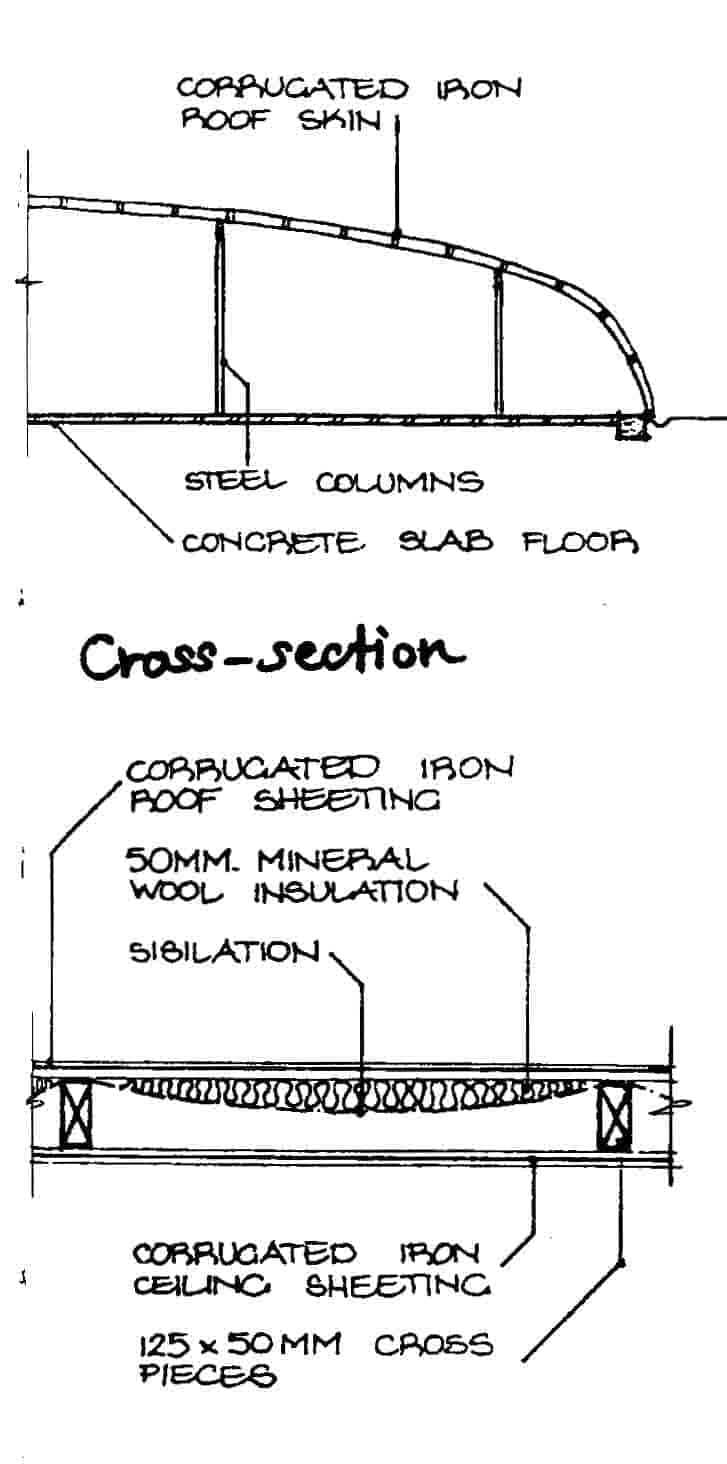

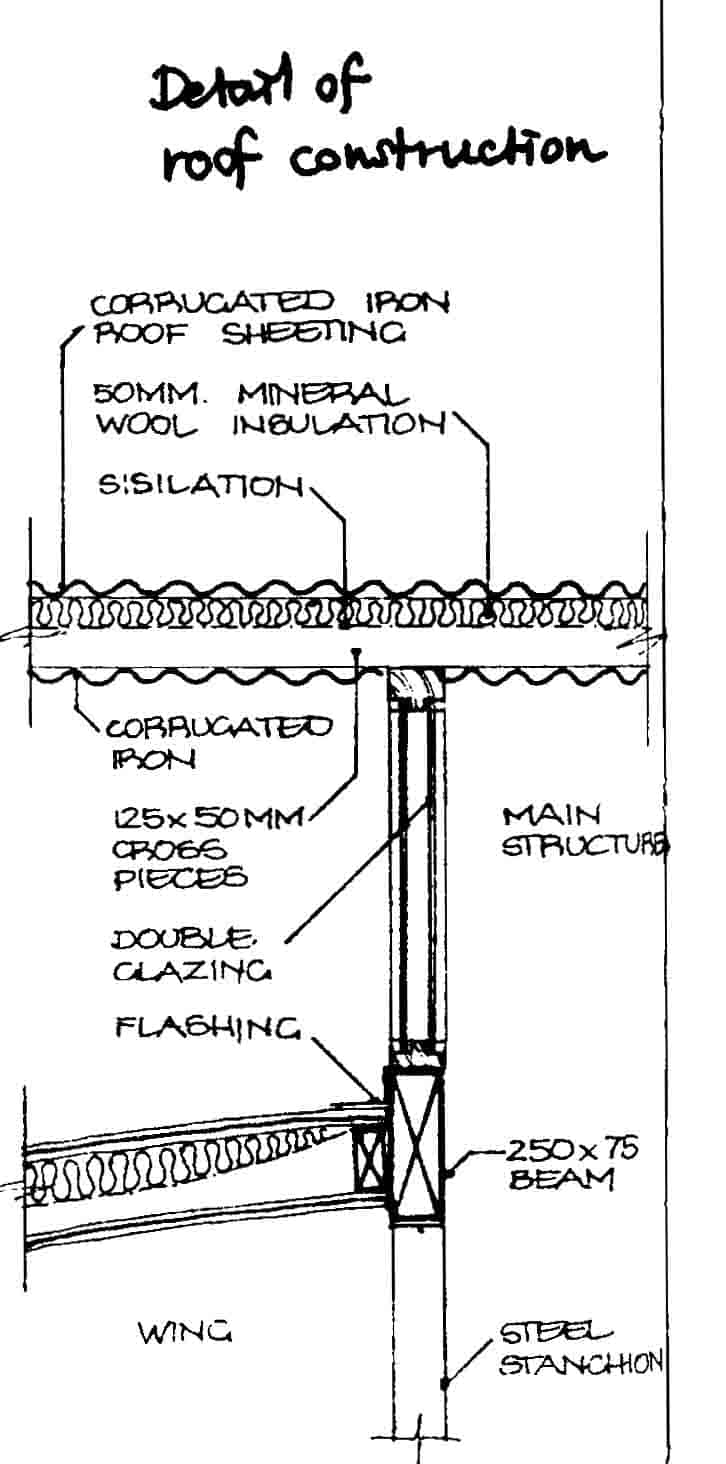

It was clear to me, however, that David had to produce something more than we saw if he were to develop his concept of hurricane-proof buildings. I told him that the usual methods of stud walling and applied sheeting, with a system of anchors from concrete slab to roof members, were not enough because the roof sheeting itself was the most vulnerable item of all. It would require an entirely different approach. I discussed how I thought Frank Lloyd Wright would attack the problem. He would argue that the proposed use of walls from which the roof was pitched was quite impracticable and that the process should be reversed. The roof should be a construction in itself, an overall skin tied to the ground

and only lifted off it to the height required by simple steel columns and beams, which would also act as anchors to hold it down. In addition, because frame and walling materials are fairly expensive in Darwin, it was necessary that any innovation contemplated should be comparable or better in price than other methods. It was obvious by merely looking over the city that galvanised iron was the standard roofing material. It was readily available, reasonable in price and had practical application. The major problem was first, to make the long lengths of iron into structural sections and secondly, to control the intense heat produced if the roof was not well insulated. Both of these problems could be simply overcome by having two sheets of iron designed to the same curve and covering the same distance. One would be set above the other and spaced, say, five inches apart with five-by-two inch cross-members at about three foot centres, which would be light, folded steel joists or timber. These would span the metal stanchions that hold the iron off the ground. Any intermediate spacing pieces could be in five-by-two inch timber at three foot centres. The whole effect would be that the roof would become a shell-shaped structure forming a parabolic curve, held into the ground by a sufficient weight of concrete at each end and supported by a light column-and-joist system at adequate intervals in between. In this way, the roof could be tied down into the concrete slab, so that no cyclone known to man could move it. Spans could be sixty feet in length if the iron were to come in one length, and greater if more than one were bolted together. Another series of iron sheeting could then be built into this span at 90° angles, so that the whole plan of the roof would look like a hot cross-bun when viewed from above. The spacings between the laminations of iron would be left open to permit air to flow through for cooling, and double-sided sisilation added for extra insulation. The raw side-edges of parallel, curved iron could be trimmed with two-by-two inch timber fillets pushed over them to make an architectural detail. The layers of iron could be colour bonded, preferably in white above to reflect the heat, and any other colour below that would relate to the internal character of the house.

Before I went to Darwin, I had requested David to make a few mud bricks out of the local soil. On examination, I found they were excellent. I suggested they be the main walling material but that they should be fifteen inches thick. This could be done by laying fifteen-by-ten-by-five inch bricks as headers. Wherever a stanchion supporting the roof members was encountered, the bricks would be cut around them. The plan itself should be as simple as possible to conform with the relaxed lifestyle of the town, and the whole design should have a 'roomless' character. There would be a parents' bedroom on one side of the house, a central living area with the cooking area in the middle and a children's wing on the other side. The curved ends that go down into the concrete ground ties would serve for storage. Interesting details would emerge if the original natural stone of Darwin, which can still be found in small quantities, could be built into the main cross walls of the house and extend a couple of feet beyond the windows and door line in the form of protective and decorative quoins.

Rather than close the house off by doors (except for lavatories and bathrooms), I suggested that water-buffalo skins could be used as draw curtains. Although they are not indigenous, buffaloes roam the country around the town in great numbers since being imported from islands to the north, and they have run wild. Some of the inhabitants do not buy meat, preferring to go 'down the track' a few miles and shoot a beast, preparing it for cooking and eating in a true, frontier manner. Robin could get carried away with it all and design Aboriginal motifs or other creative drawings on to these hangings to make it all very 'Darwin' and personal. I proposed that the laundry and utility area of about twelve foot square could be placed in the transverse section of the roof design. They would be separated from the rest of the house with verandahs at least six feet wide all round.

The transverse roofs would be of a similar construction to the main wing, and fitted to the latter by a steel joist that spanned the stanchion system of the main house. They would be a little lower than the curve of the main roof and could provide clerestory sections of double glass, as long as good flashing was provided for protection against extreme winds. These wings would extend a considerable length both front and back, and would of course be tied down like the main roof. If the outside joists on all wings terminated the main iron spans at a ceiling height of six to seven feet, the curved sections could all be rolled on the edges with the same detail and bolted to the main roof and to the joist system.

It would be important to drill all the fixing holes for the outer roof at least, to prevent any possible tearing of the iron. Gutters would be not required as the roof would be mounted into the concrete at ground level. A suitable channel, moulded into the concrete, would catch the water and take it away in underground stormwater drains if necessary. It should be noted that the earth walls were recommended not only for character but temperature control and their relatively low cost. They are only infill walls, although they would add greatly to the quality of the structure overall.

This rather revolutionary concept had to be digested by David's engineering mind but, when I mentioned Nervi the great Italian engineer (World President of the Instinctive Inventors' Association), David commented, 'He is the best architect in the world. I have a book of his'. He suited the action to the word and handed me his copy. I opened it at random and there before us lay a similar principle - in concrete instead of iron. Not a vertical line was in sight; everything was in parabolic curves. The next page was the same. Flipping right through the book confirmed the concept in every photograph. I pointed out that he could design some interesting spacers and fasteners for the double roof ceilings, and proper flashing and systems of jointing where the secondary curve joined the main structure. There are many sophistications possible in this method of construction. On hillside sites, for instance, one curved section could surmount the other and make a series of pure shapes under the general disciplinary lines of the curves - a kind of corrugated-iron Sydney Opera House.

Our two-hour discussion put us in the mood for a swim and a barbecue on the beach. Despite the fact that it was the 'cool' season, the water was luke-warm. We had the whole beach to ourselves, as far as the eye could see. It was a wide world, and still very 'early Australian', primitive and natural. I was forcibly reminded of how I had felt when I had returned to Australia from Europe. three years earlier. All the ingredients were there: the sense of peace, space, colour, light and antediluvian landscape.

I flew back on a slow plane through Katherine and Tennants Creek to Alice Springs, over the eternal landscape that spoke with such authority about the enormity of creation and the humility it should generate in our minds. Such a landscape translates the issues of everyday survival into three simple elements that continue to elude the systems of this century. The elements are enough breathable air, enough drinkable water and enough arable topsoil to sustain life in our universe.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >