Alternative Housing, The Audacious Improvisors

The Audacious Improvisors

Author: Alistair Knox

The individual approach to building

In environmental building 'the race is not always to the swift nor the battle to the strong'. My first evidence of this was when Alma Shanahan spoke to me about building in mud brick back in 1951. 'Alma', I pleaded, 'please don't try. I know several competent strong men who are simply never going to complete their houses'. I thought that Alma was about the last person in Eltham to take on such a building. She had been a girl-friend of artist Clifton Pugh until a little earlier, and had taken up land on her own near his at Cottles Bridge after they separated. She didn't seem a strong Amazonian type that I felt should be the sort of person that would succeed. I had been through more than a few agonies at the time because of the duration and effort of earth building. Alma laughed a lot and gave the impression that it was all too easy. But I was to be completely disillusioned by her light-hearted approach. 'I'll do it' was about all she said to me at the time and she proceeded to do just that.

She telephoned a few months after our original conversation to tell me she had practically finished the building. Her only real difficulty arose when she tried to make mud-brick cupboards! Whatever she may have appeared to lack in building skill, she more than made up for in enthusiasm and tenacity. Since that time she has settled into being one of the really good potters of the district. She has always maintained an independent mind and an unceasing flow of work that is fresh and positive. It was one of those unusual cases where she made the mud brick rather than it making her.

Another such case was that of Brian and Carolyn Brophy twenty-five years later.

The Healesville project

Five years earlier Brian had called into our office to discuss the possibility of mud-brick building. I took him to one or two jobs and showed him how to go about it in the simplest and most practical manner I could think of and promptly forgot him. I did not hear from him again for three years. Then his wife Carolyn phoned one day to ask if I had any call for stained glass for earth buildings because she had started fabricating them. I suggested they come over and talk about it. It was not until we had been together for half an hour that Brian asked if I remembered our earlier meeting. I told him I did not, so he described our conversation and said he had gone off and built the house.

He flicked through their album of photographs of stained glass until he came to an earth building and showed it to me. It was a large and impressive structure, mostly two stories in height. 'I just did what you suggested', he said modestly. 'It took me about three years of going out from where we lived in Brunswick to the site on the Don Road beyond Healesville each weekend.' The distance was forty miles each way. His wife and children went too. I was full of admiration at their unassuming ability, and it was arranged that I should go out at an early date to see it for myself.

One of the most unusual aspects of the whole proceedings was that he was a professional classical guitar teacher. Both of them were in marvellous health and looked like two of the sleek cows in Pharaoh's dream - an unusual condition for people who have just finished a twenty-seven square earth building. Neither had that harassed or haunted look I have sometimes seen, which can make mud-brick builders look more like those other seven lean cows that ate the sleek ones in the ancient dream.

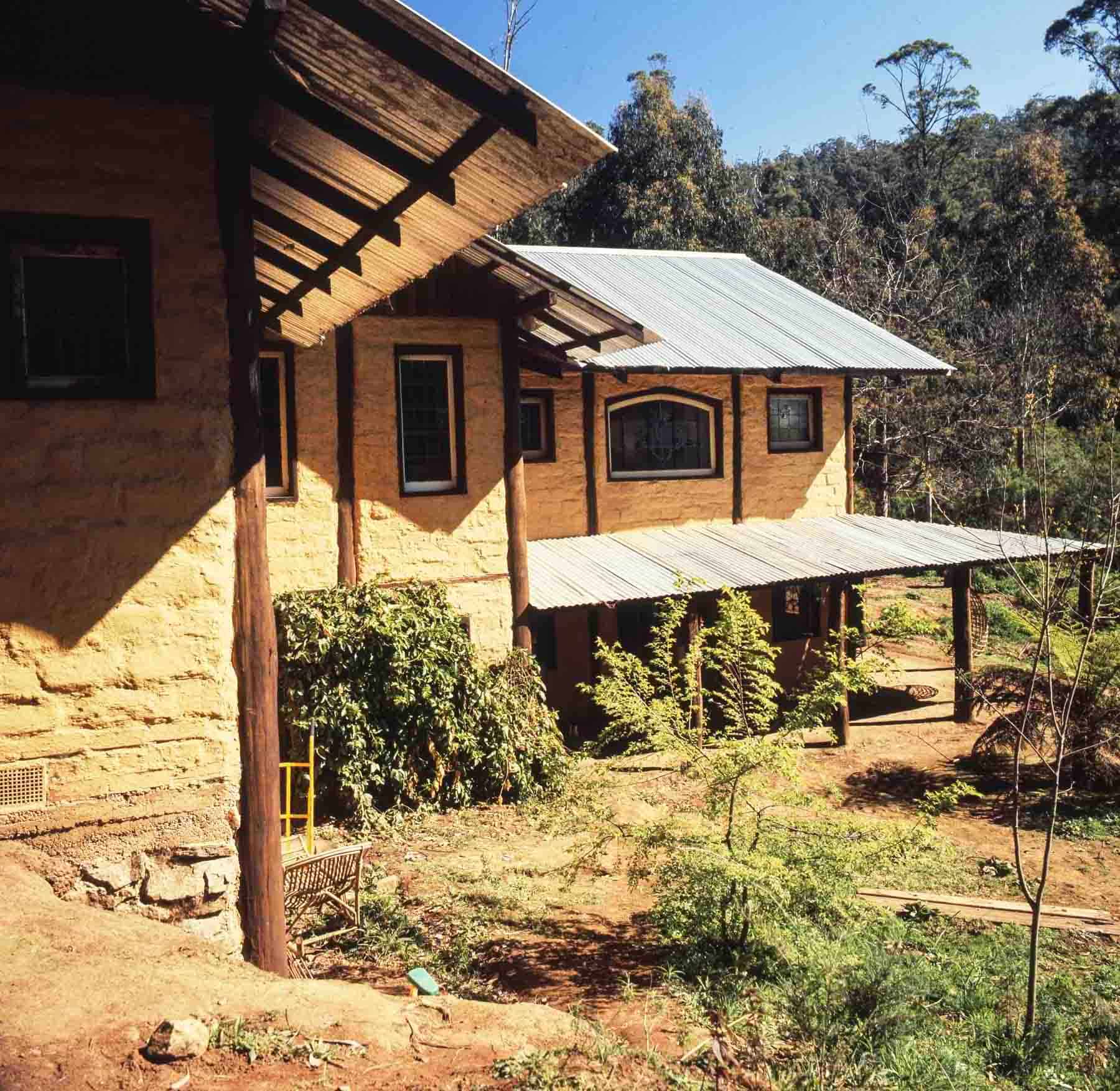

Approaching the Brophy house at Mount Toole-be-Wong from the road revealing an absence of guttering

Approaching the Brophy house at Mount Toole-be-Wong from the road revealing an absence of guttering

The greatest surprise was the price. When I asked what it cost, suggesting about $1,000 per square, he looked horrified. 'No, no', he protested. 'It was only a few thousand altogether - $5,000 or thereabouts, but I'm not quite sure', he replied.

About a week later a young couple, who had just produced the first issue of an environmental quarterly named Simply Living, arrived from Sydney and stayed with us for a day or two. I suggested we visit Brian and Carolyn Brophy. I thought their glass work and building would be of interest to them for a subsequent issue of the magazine. As we drove from Eltham to Healesville, I informed them that they were on the original route from Melbourne to the mountain goldfields of Woods Point and Jamieson. Cobb & Co. coaches took six days to make that precipitous journey. Examining some of the old tracks which still remain, one wonders how they made it at all. Vertical mountain sides, precarious ups and downs through valleys, exhausted horses, bushrangers, winter snows and the mighty mountain ash trees soaring 300 feet above must have created a sense of awe and wonder in the most hardbitten gold-miner. Surely it was here that the Australian character was forged. As the gold receded in quantity, the reverence for the infinite power and distance of the bush emerged.

Healesville is a holiday township at the gateway to the Great Dividing Range, and we finally found Carolyn Brophy at work in a second-hand furniture shop they had recently started. Brian was down at Monash University when we arrived. He was providing the guitar musical background for a Lorca play. I went out to purchase cheese and rolls for lunch to await his return. We sat at a table behind the second-hand furniture, which was lightly sprinkled with powdered glass from the work Carolyn was doing. I kept glancing anxiously at the underside of the rolls before I ate them to see that none of it was embedded in the crust. Then Brian came in and sat down and started to play. As Carolyn poured the tea into the saucerless cups, we were enchanted with the beautiful quality of his music in the midst of the furniture, the powdered glass, the cheese rolls and Lorca. He ran through improvisations he was making as he read the play spread out on the floor beside him. It was both foreign and indigenous at the one time.

We were soon on our way to the house which was about six miles up the mountain road. As we walked down to the site, the bright orange clay walls rose to an impressive height. The building was constructed on the post-and-infill system, including horizontal, natural tree-trunk timbers at the first floor level. Apparently Brian and Carolyn had got them into position in between his city guitar lessons. It had certainly not impaired his playing ability. The house was roofed with the usual corrugated iron and I noticed that there was a short section of spouting missing. I asked the obvious question as to how they could catch their water because of this omission. Brian remarked in the most relaxed manner, 'There is a large disused dam on the other side of the road up there, so we just siphon the water across'.

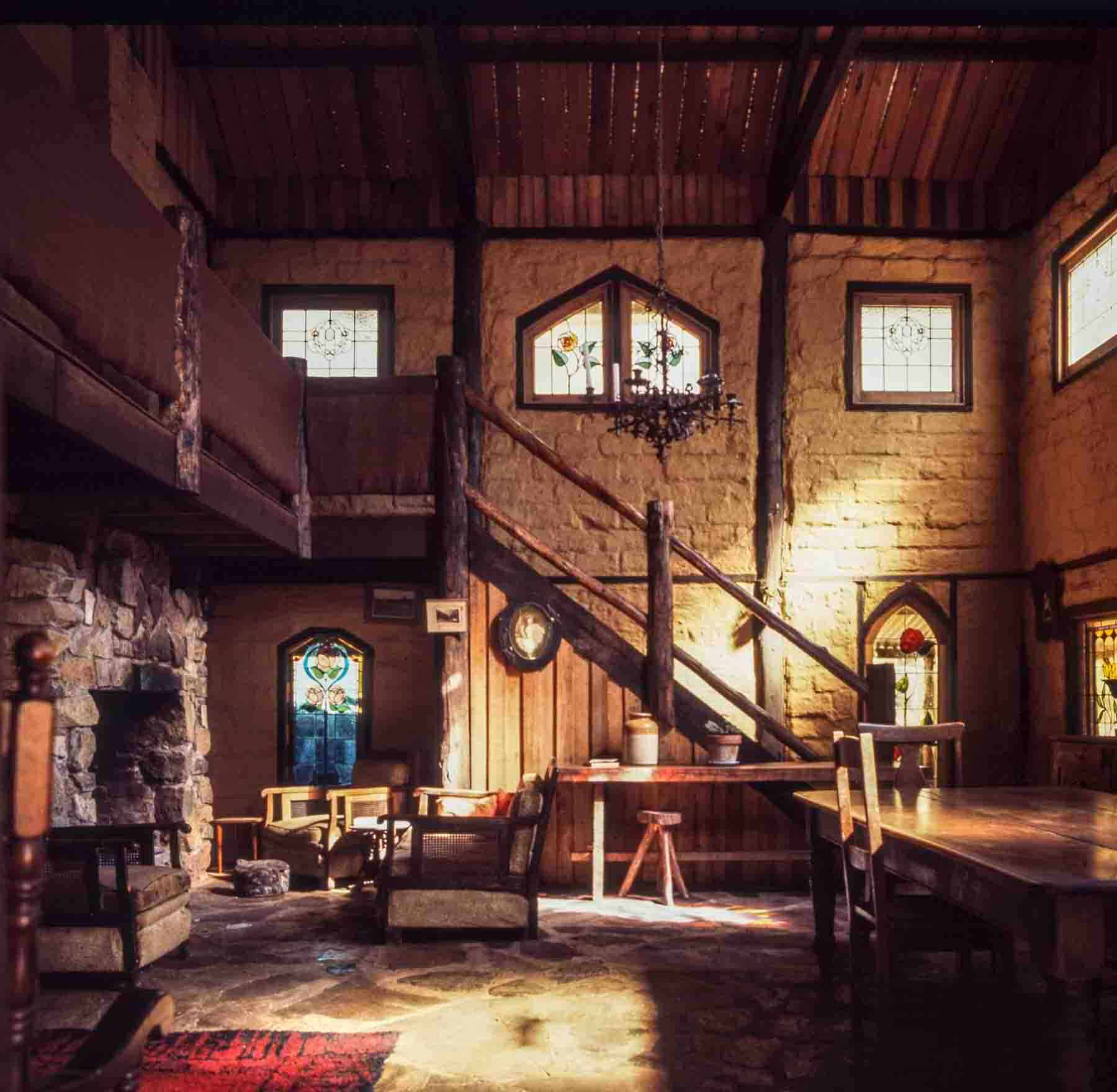

Once inside the building, we walked up a rustic stairway to a gallery at the first floor level. This gave access to some bedrooms at the rear that were welded back into the steeply-sloping land.

"Making a stained glass window - a family affair

"Making a stained glass window - a family affair

The most beautiful room in the state of Victoria and at the lowest cost

The most beautiful room in the state of Victoria and at the lowest cost

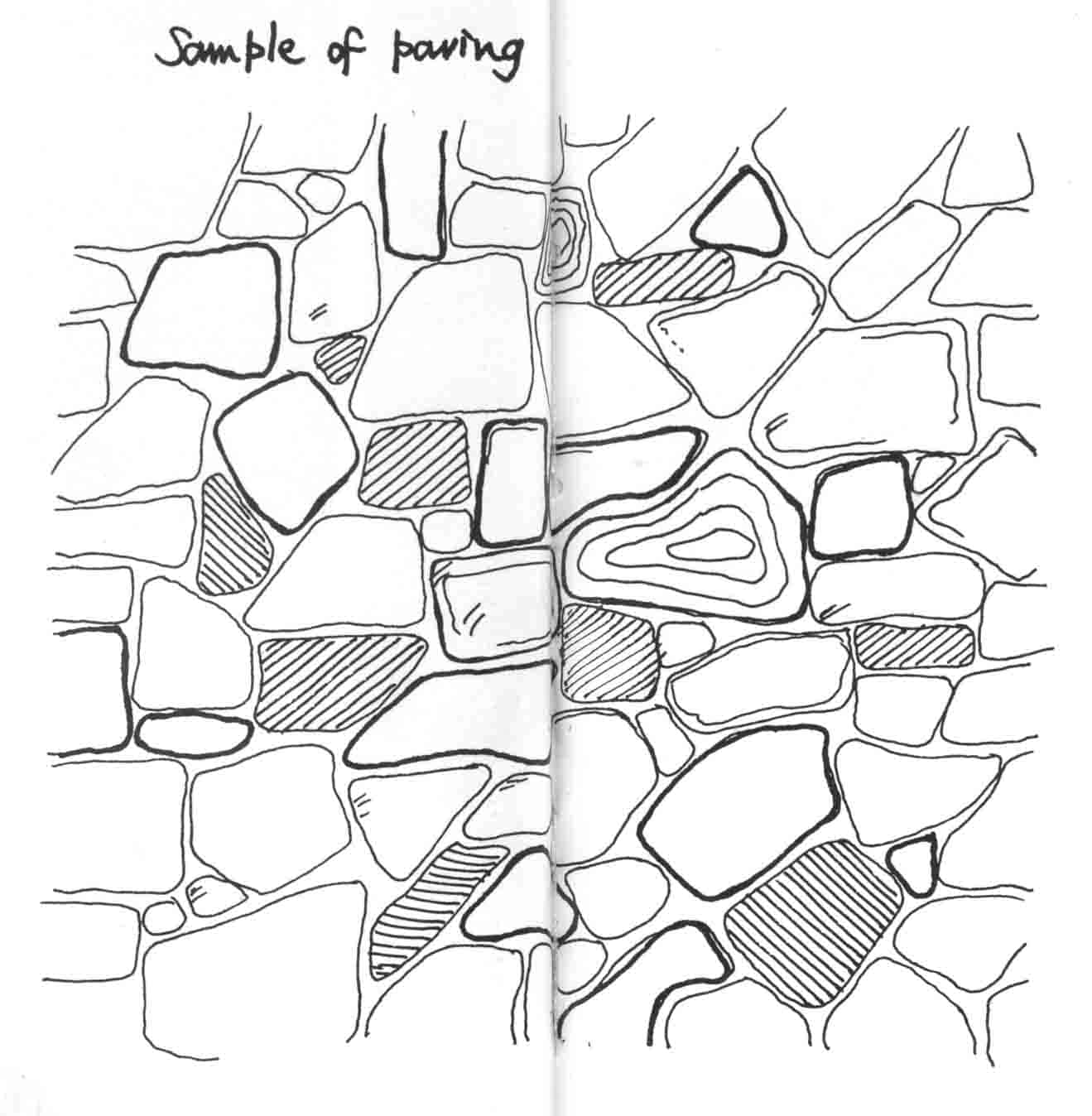

'What do you think of the floors?' he asked, indicating the random stone paving below.

'It's practical and interesting', I replied.

'I just picked it up off the road and turned up the flattest faces', he answered. Everything about the house had this improvising and ingenious quality. It all worked well, yet was all very simple - not in any way fussy like the American Woodstock houses. It was true and inevitable and of good proportions. Brian and Carolyn were people who understood that the eye is the final arbiter. Their decisions carried consistent evaluative judgments that made for satisfying results.

The Australian character is at its best when it is coming 'from behind', and at its worst when it is 'in front'. The great traditions that have built up the European mind tend to cause it to conform to its heritage, but authentic Australians revel in the innovation and inventiveness of the pioneer. Brian and Carolyn were excellent examples of this theory. They looked as though they had never become anxious about their building and its result at any time. They simply did it and, behold, it was very good!

'You have no electrical power?' I questioned. 'Are you using bottled gas?'

'No', said Brian. 'We were going to put the gas on but, when we saw how beautiful the candles were, we couldn't bear to.'

They made quite a few windows of stained glass for the house. With the pitched ceilings, these gave the building an ecclesiastical look. It was these windows that set them off building the house themselves. The front door was also in stained glass and a large piece of flat iron was wired over the bottom section. 'That's the hole the wombat made', Brian said, seeing me staring at this strange sight. 'It keeps coming to the door.'

One day Caroline phoned me and asked what I thought the property was worth, as they were intending to sell and move to South Australia - they felt the warmer climate would suit them better than the cold mountain country of Victoria. They were following the pattern that is part of those seeking the simple alternative living style to that of getting caught up in the corporate state-system that has percolated through our thinking. It is an interesting fact that the two major urban complexes in Australia, Sydney and Melbourne, are being vacated in favour of the lower populated cities of Adelaide and Brisbane. Surveys reveal that 52% of people living in Melbourne would prefer to live in smaller communities. In vain the manipulators of industry and commerce order them to obey and work there like the good little people they once were. There is a hardening of attitude against perpetually buying things that are not needed. Underneath the pattern of the 'boom and bust' economic system, there is a new groundswell for getting away from it all. South Australia and Queensland have warm and sunny climates, and are old-fashioned places where people can still successfully compete with materialism. The South Australians are perhaps better off than the Queenslanders whose government is characterized by some of the most profit-hungry and environmentally-disastrous attitudes in Australia. But, despite its rulers' native depredations and greed, Queensland's landscape is rich and beautiful, and well worth a try at building in. In the end the Brophys stayed where they were, because there was no bushland they could buy in South Australia - a tragic indictment of what we are doing to our unique landscape.

The Avoca project

The bush the Brophys were unable to find in South Australia was the 'wild bush landscape' of the deep emotional variety they experienced at Mount Toole-be-Wong, outside Healesville. I did not hear from them for a time and thought that they had settled down again in their old home. This supposition exploded when I received a letter to the effect that they were building again - this time near Avoca, a small town west of Ballarat. When they called in on us, they explained that this house had only about nine squares of floor area with three squares of attic space above. In this instance they were using rammed earth instead of mud bricks. The wall was only about nine inches thick and the whole was integrated with posts at specified intervals. It was a kind of combination of mud brick and pise, or more specifically of earth and stone rubble.

They have an unquenchable fire for building with a spirit that matches any difficulty. I asked them if they were on the dole, to which they replied indignantly, 'Oh no, we receive $45 a week rent from the Healesville house'. How marvellous to think that they could start a new building on $45 weekly, only slightly above the current dole rate for a single person at that time.

I fitted in a visit to their site in conjunction with another potential alternative lifestyler, a school teacher and his wife who were planning a vineyard existence not far-away. We drove to Avoca and then on through a breath-taking, primitive desert-forest,

full of survival power and ageless beauty. We finally found the Brophys located at Glenpatrick. This seldom-heard-of place rarely appears on maps. However, we found it was two miles beyond another location called Nowhere Creek, which does not appear on the maps either. It was certainly remote. Their new building was halfway up a hill with partly open country on the high side and dense bushland on the low. It was at the extreme end of the road that passed through Nowhere Creek to Glenpatrick and ended in a forest reserve. Brian and Carolyn were quite grumpy about the excavator for their new site. He had charged them $150 - a huge sum of money to their minds. It had only taken him three hours. When I asked what they expected the whole building program to cost, I almost fell over when they said their estimate was $1000. In my own experience a little earlier I had found it cost me over a $1000 a square to erect the small extension we had made to our own house, despite the fact that I had stolen a lot of the timber from myself and did not have to pay anything at all for the excavation.

The Brophys are the most remarkable builders I have ever encountered. On the occasion of our visit it was alternatively showery and sunny weather. Brian was working on the roof structure between showers and talking when it rained. He had obtained his roof members from the adjacent forest reserve. These round poles were arranged as square rafters, with diagonal braces in between that completely firmed up the whole structure. Carolyn was paving the kitchen floor when we arrived. She had a basketful of flat stones beside her that had been taken from the nearby creek, and was laying these straight onto the ground and pointing them up in cement mortar. The whole building was a direct application of natural materials to form a shelter. It was wonderful how they contrived to build so cheaply. Totally united in purpose as a couple and also as a family (they have two children), they all worked together as one person. The results were quite outstanding. When comparing what they were able to produce with even the simplest building derived from the usual methods, it was not only twenty times as cheap, but in many ways twenty times more beautiful to look at ... and better to live in.

Their contriving and making do is partly dependent on the strict financial limitations they experience and I believe the whole building scene would be better if this principle were more rigorously applied to all other buildings. Even in the few multistorey structures currently being built this would be so. There is a case in Melbourne where bluest one veneer has been attached to structural walls. It refuses to stay stuck and crashes to the ground. It will all need to be removed eventually. The Brophys' problems may not be of the same scale as a city building, but their house does what a city building cannot do. It radiates a human quality, is built by nonprofessionals with structural soundness and achieves a satisfactory lifestyle.

The Brophys put their Healesville house on the market for $60,000, of which the land was estimated at $20,000. As soon as it was advertised, the agent was so inundated with prospective purchasers he had to take them up in groups. The building was attractive to nearly everyone who saw it, but it did not have electricity or gas and there was no internal heating - and that area is cold, with snow in winter. This was too much for those who were making the transition to the alternative life. Had they spent about $5000 supplying those conveniences, I feel sure they could have added twice that sum to the sale price and got it without trouble. A couple of weeks later the Brophys called in to tell us they had sold the house for $55,000, which I thought was cheap enough. To them it represented a fortune. Sadly, right on the day of signing the contract, the purchaser had to withdraw because he could not quite resolve his finance. He was a university lecturer and was being assisted by relations who, when they saw it was a mudbrick building, grew faint-hearted and would not help in the purchase.

Another problem was added to this dilemma. It is now a local government requirement to obtain an occupancy certificate, even if they are an owner-builder, before you go into a new house. This had not been done. Subsequently the municipal representative inspected the work, but found a series of regulations had not been complied with. None of them were structural. One of them was that the distance between ceiling and floor in the dining room was seven feet eleven inches instead of eight feet. As the floor was of stone, it meant pulling it all up and starting again - a formidable task. This meant that these items required attention before the house was removed out of the 'slum' class.

It is of course important that building standards are maintained and that buildings are 'habitable'. The pity is that one inch in ceiling height should cause a beautiful house to be substandard, while many of the Healesville houses are lined externally with fibrolite, a three-sixteenth of an inch cement board that looks and is cheap and fragile. It's the old story of 'the letter killing and the spirit giving life'. Building standards are so often legal technicalities describing minimum standards for minimum quality material. They make no allowance for alternative materials, which may not be expensive but may be perfectly functional. With mud bricks just emerging as an appealing building material for those initiated into their simplicity and beauty, they are prone to become the singular butt of conservative local councils.

Dealing with the authorities

Home builders, especially those using alternative materials, can often save themselves a lot of needless worry if they go about their dealings with local councils in the correct manner. The rules are simple. First, you must acknowledge the building surveyor's authority. Secondly, you must ask for the proper examination of the footings and other mandatory inspections during the course of the building. Any other course is a simple method of committing building suicide.

I have found that most surveyors are reasonable and helpful if you abide by their rules. It is imperative that you do not make an enemy out of them, even if you personally don't like them or think they are being carried away with their authority. If they become totally unreasonable, their interpretation of regulations can be submitted to referees appointed for that purpose. If you have a case, you will never have to appear before them. The surveyor will concede before you get there.

The difficulty with the Brophy building was that it was required to conform to regulations that did not relate to its special character. It is essential that there be building regulations to guarantee the stability of a structure and provide sanitation for its inhabitants, but these controls can become oppressive when expressed in regulatory form. They give full rein to the bureaucratic mind, and tend to stifle those creative and imaginative qualities that enhance any civilised community. Fifty years ago there may have been good reason for these provisions, but today every proper building is designed to provide an appropriate environment for people rather than to skimp on money, which is what much of the present code is all about. The wide variety of materials and design techniques today have made many of the older structural requirements redundant.

I believe we need a more flexible approach to the whole matter of building requirements, whereby an application for a building permit would first be evaluated by an informed panel of referees before it goes to the usual municipal authorities. This panel would apply an aesthetic as well as a minimum structural standard.

The Brophys have succeeded in building the cheapest house I have ever seen. It is also one of the most beautiful. Young couples everywhere should not be prevented by the current standards from building a house because of the high costs involved. It must be admitted that there are some cases of benighted officialdom trying to block imaginative ideas ... and leaving the community poorer for it. Whatever the attitudes of the past, the future must be different. The medium has developed too far to be swept under any municipal carpet.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >