Alternative Housing, Our Recent Yesterdays

Our Recent Yesterdays

Author: Alistair Knox

A personal recollection

THE shape and nature of the city of Melbourne has greatly changed from the one in which I grew up. In 1914, just before the First World War, I was two years old and the population was less than one million. The geographical boundaries were only a fraction of what they are today, despite the fact that the easy terrain was already causing it to develop into a rambling, widespread metropolis. Its humble birth in 1834 was succeeded by the boisterous Gold Rush of 1851, which soon turned the whole State of Victoria into the richest colony in the world - at a time when all the major European powers were dividing Africa and other primitive lands and adding their assets to their individual kingdoms.The layout of Melbourne's quietly undulating landscape was radial because of the course of the Yarra River and its many tributaries. The original city surveyors had laid a grid pattern over the natural radials, except for a series of three-chain stock routes forming Dandenong Road, Bridge Street, Royal Parade, Flemington Road and Victoria Parade.

The transport system that followed the radial lines from the centre worked well, until the grids began to stretch out and fill in the spaces between their ever-extending arms to form large, uninteresting suburban deserts.

Before World War I

But Middle Park on the shore of Hobson's Bay, where I was born, was different. It consisted of a continuous flow of single or two storey houses on small allotments facing wide, tree-lined streets. The front gardens were neat patches of lawn, herbacious borders and a prevailing rhythm of cast-iron lacework verandahs. The great plane trees, planted at methodical intervals in the nature strips, had grown so large that their branches were meeting overhead in the middle of the roadway. Then there was the eternal interest of steamboats and sailing ships moving in from Port Phillip Bay to moor at Nelson Pier, Williamstown, Town Pier and Port Melbourne, or swing at anchor near the Gellibrand Light. From spring to autumn the whole community would meet on the wide, clean, sandy beach to swim, promenade or stretch out and sunbake. There is a strange phenomenon in Hobson's Bay. Under certain atmospheric conditions the further shores appear to be higher than the middle of the water and the ships lower than the land, At other times the position is reversed and the shore on the far side seems to disappear and the distant You Yang mountains are just visible peeping over the edge of the convex rim of the sea.

At the age of two years, my greatest joy was to ride down to Marine Parade and the beach on my father's shoulders as the sun was setting over Williamstown', The bare yards of the sailing ships tilted at many angles, silhouetted against the warm orange light, were a great source of wonder to my infant fancies. I believed that Williamstown itself was India, because it was the first land you sailed to when you left Australia. I didn't worry about England being out of sight; I knew it was much further away.

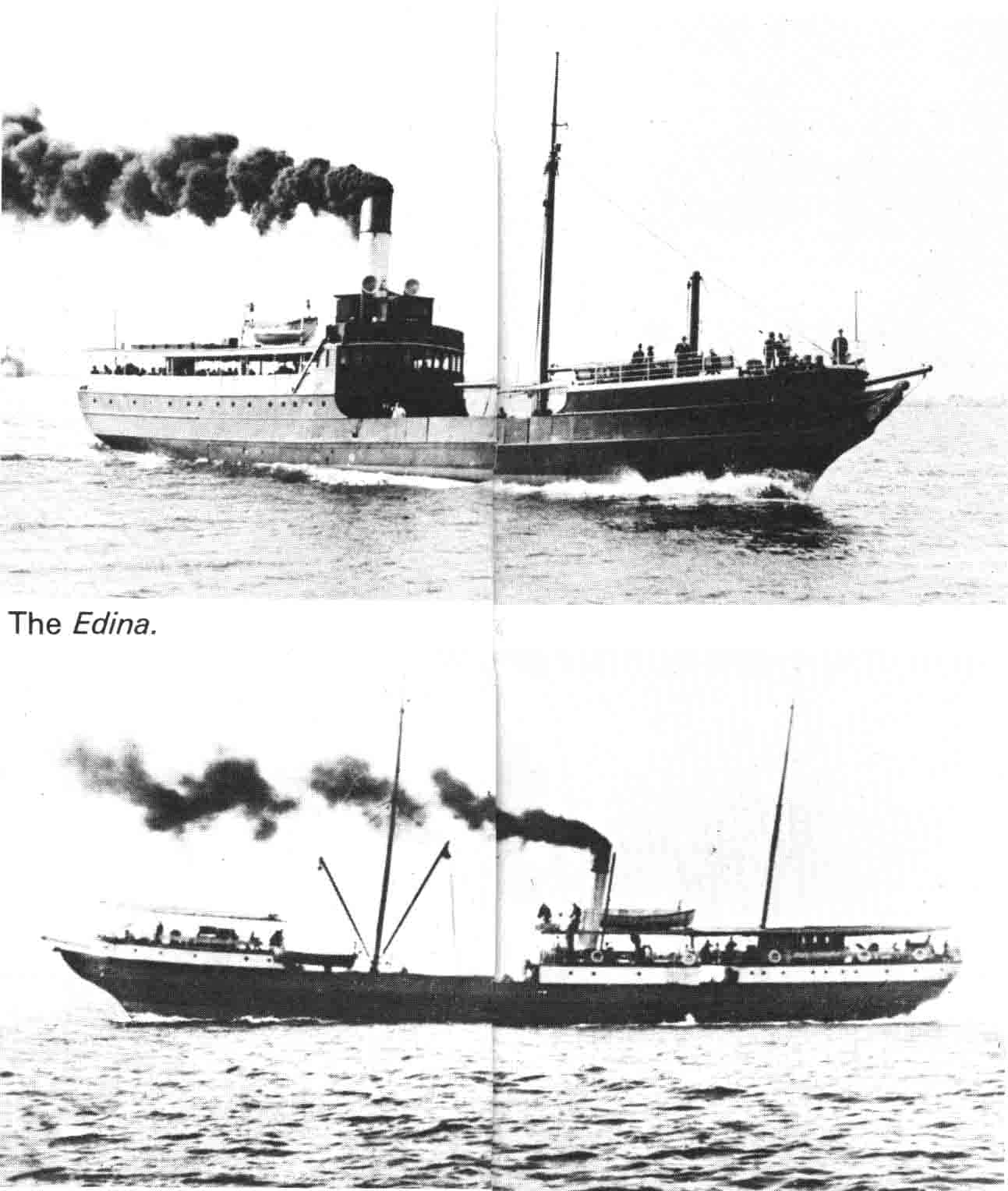

The Edina

The Edina

A light, south breeze would often spring up as we watched the Edina, an ancient steamship that had seen service in the Crimea, making its way up the bay from Geelong and Port Arlington. When the wind blew from the same direction as the ship was travelling, its one, tall, narrow funnel would pour clouds of black smoke into the sky in a sweeping curve that stretched ahead of it, very much like a Turner seascape such as The Fighting 'Temeraire',

In the deepening twilight, house lights would come on sporadically along the beach front that gently curved away towards St Kilda, casting pale yellow reflections on the water. We would wait for the lamplighter to commence igniting his chain of lights along Marine Parade, It was a very broad road with a wide garden reserve in the middle, and the lights themselves had graceful, pear-shaped glass shades with white enamel reflecting-caps on top. I was allowed to stay until the light was lit near where we sat. By the time it was touched into a soft, yellow glow by the long rod the silent lamplighter carried, it would be quite dark, He and his bicycle would be lit for a moment, then would silently disappear again into the darkness. Only the faint whirr of his tyres would give any evidence of his presence or where he was heading.

Long lines of traffic moved up and down the street on a warm evening. Jinkers, other horse-drawn vehicles and early model motor cars swept past at speeds varying from eight to twenty miles an hour.

Luna Park as it was

Luna Park as it was

The scenic railway at Luna Park could be seen quite clearly: its course was traced in electric lights. On still evenings the exhilarating screams of the lady passengers could be faintly heard as it hurtled down its precipitous descents and rose up the other side. Each vehicle on the railway consisted of two cars, controlled by a red-coated attendant wearing a gold-braided cap. He threw a lever which grasped the cable as the cars ascended and let it go again when they reached the tip of the incline. He made an elegant figure as he leaned, first back then forward, in graceful rhythm as the car descended and rose again. He also commanded a marvellous view of the bay and the city when he was circling at this great height, and had an everchanging view not unlike that of its guardian angel. Curving, gliding, diving and rising again, he kept watch over the town and its inhabitants, as the stars started appearing and the steam merry-go-round whistle piped its familiar sound. Further away laughter could be heard coming from the inside of the canvas-sided Pierrot Land as the show got under way.

It was a form of quiet, uneventful journeying from the cradle to the grave. It was generally accepted and enjoyed through the boom and the Depression, and the World War that followed, by the lower middle-class bourgeoisie to which most Australians belonged. Few ever questioned its advisability or saw a hope of radical change. To misquote Shylock, 'Mediocrity', not suffering, 'was the badge of all our tribe . . .'

After World War II

It was in 1946, following the end of the Second World War, when many Australians discovered that a secure job was the most insecure thing in the world. The steady pay packet which had been so comforting in the Depression was becoming a barrier to a new and real fulfilment.

New choices were emerging in every avenue of endeavour. The word 'superannuation' had lost its charm, and unimaginative stickability from the cradle to the grave was a diminishing measure of a man's acceptability and value. Even the most unenterprising felt that a period of unparalleled expansion lay just over the horizon. It had the atmosphere of a gold rush. The first to get there staked the best claims. This condition broke urban Australians into two major groups: those who took the risk and got out, and those who funked out and stayed in their jobs. The great majority of employed people wanted to 'have ago', but many of them were afraid because of their dependants and the spectre of a future recession. The more conscientious they were, the more cautious they became. Those with nothing to lose never thought twice about it. The prosperous conditions of the next few years divided them more widely. The adventurer tended to gain a richer, freer lifestyle, while the good and the concerned seemed to work harder for less. It fostered a social democratic spirit that lasted for thirty years,' despite a series of depressing Conservative governments, until it found its late short flowering under Labor from 1972 to 1975.

My own position was further complicated between these alternatives because of a disintegrating marriage. I had no intention of remaining in my pre-war job in the bank. I intended to design and build environmental buildings, but the necessity of providing for the family and the shortage of building supplies and workmen made conscientious transition difficult. It was three years before I took the plunge.

Nearly every Australian in the Defence Forces dreamed of the day of his discharge. Those who served in the Pacific and knew something of the Japanese feared that great day might never come. Even after the defeat of Germany, it seemed a hundred years away. To my huge delight, I escaped through sickness a few months before the final surrender. I was only vaguely aware of what this would mean until I found myself on the duty boat, travelling from my home depot at Williamstown to Port Melbourne to return the naval equipment that was only on loan. The familiar scene took on a new meaning. Here were the last nostalgic shipboard moments, the final carrying of the lashed hammock and the end of the kitbag life that I had both loved and hated. The next day I would have to report to the bank. I gazed across to nearby Middle Park beach, where I had enjoyed so much childhood freedom, wondering how to escape from the economic straitjacket. My family responsibilities required regular income, that would reduce the scale of life and make me old before my time.

I had been a ghastly bank clerk and, throughout the war, those who had continued to work there had to slave like men possessed. I couldn't bear to think about it. I only knew one doctor really well and he was a gynaecologist. I had no alternative but to telephone him and tell him I was mentally and physically unfit to resume work, and wanted a medical certificate. He gave me one for six weeks. 'It's the best I can do, considering what I am', he said. I took it gratefully and so did the bank. But little peace descended on me as I tried to re-orientate myself back into civilian life. The sea was still all around me. The beautiful little timber ships we sailed in, with their teak decks, jarrah hulls and smooth-running diesel engines, were forever leaping about underneath my feet. We had journeyed between tropical islands and uninhabited atolls and followed cyclonic storms. In the words of the naval prayer book, we were 'those that go down to the sea in ships and do their business in great waters; these see the works of the Lord and his wonders in the deep. For he commandeth the stormy sea and lifteth up the waves thereof. They mount up to the heavens; they go down again to the depths; their soul is melted because of trouble. They reel to and fro and stagger like a drunken man and are at their wits' end . . .' I had become addicted to the life and saw no chance of escape from its fascination. I planned to buy some sort of small ship after the war and start island trading, but at this stage such an opportunity was impossible.

I finally found myself chained to the 'dead wood of the desk'. Shortly afterwards the atom bomb was dropped and all warfare ceased. There was a short period of intense relief and then the stories of millions of displaced persons, ruined cities and half obliterated Europe - to say nothing of the destruction of much of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that filled our hearts and minds with nausea.

It took time to get things moving, but we were still confident that new and exciting possibilities lay ahead. I was too old for the fulltime training scheme, but received a part-time course in building construction and drawing at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. It was an exciting year, despite my itchy sea feet. A gifted architect instructor brought the course to life and owe half of my present lifestyle to his inspired teaching. I actually designed and built a house at the same time as I was being taught. Building was a slow process and I just managed to keep the lessons ahead of the work. The other 'half' is derived from my association with the Eltham environment and the people it has produced.

In 1947 the building material position became even more difficult, until it virtually dried up altogether. It was for this reason that I turned to earth construction and environmental design. I have been involved with it ever since. Earth was free and available, and combined perfectly with other natural materials which were mostly cheap - being held in low esteem by those who thought the new age meant new materials rather than good ones.

Eltham was the only municipality that would issue a permit for an earth building in those early days. Thus I found my activities confined to that beautiful area for the next three years, except for a farm project in the country. In 1948 we shifted house to Eltham, to live in a location that overlooked the central valley and to commence a completely different life.

I soon discovered it was the special landscape of the district that also produced the community that lived there at that time. They enjoyed a way of living that survives to this day. I clearly remember getting a lift in a two-wheeled work cart when I first came to know the district. It was driven by Sonia Skipper, an artist and builder, and drawn by an enthusiastic horse with oversized hooves. Anxious to get home for the night, it clumped along the dirt road that runs beside the Diamond Creek.

It was late in the autumn afternoon, but the sun still shone through the eucalypts higher up the slopes to give dappled sunshine in the valley. The air remained warm, except for a few sudden patches of cold where the sun had disappeared for the day. These chilled the face and made -the eyes water as one sped through them. The first whispy strands of evening mist were rising around the odd pools of water that lay in the creek floodplain, when I was suddenly gripped by a melancholy yearning that this moment of disembodied beauty could continue forever.

It was the first time I came under the spell of the 'natural genius' of the local landscape. I have experienced it a thousand times since and it has always been the same. It is not just a beautiful scene: it is a living presence. It nearly always seems to enjoy that primitive awakening to life that is the privilege of most other landscapes only in the springtime of each year. It lies closer to the genesis of nature than the more sophisticated landscapes of the northern hemisphere. Here the Creator's brush strokes are less varied, but broader and unhurried and more powerful, but his effect is true and finished. It speaks of light, space and power.

Geographically Eltham covers more than one hundred square miles and is situated in the fork of the Yarra River and the Lower Plenty River on the south and west and the Great Dividing Range. on the north. The whole terrain consists of small, bouncing hills of similar height and spacing, that mostly conceal the great mountains further east and generate a series of intimate, inner landscapes. Within these valley recesses the varied, but generally temperate climate abounds in transient moments of in-between times and inbetween seasons. On early mornings and late afternoons, red-gold sunlight mingled with quiet mist is full of the smell of the bush and the cry of the birds.

The small country village and its landscape literally drew the salt out of my body, so that the pull of the eternal sea soon lost its power. The mysterious bushscapes, combined with the absorbing activity of discovering the craft of building in earth, timber and stone, took its place.

The central Eltham valley runs north and south with hills rising steeply on either side to a couple of hundred feet. The Diamond Creek flows along it until it reaches the Yarra a mile or so to the south. The railway to the city also ran through the valley and, as it nears the station, is supported by a timber trestle bridge made from great eucalypt tree trunks. It extends for about a quarter of a mile, where it traverses the creek.

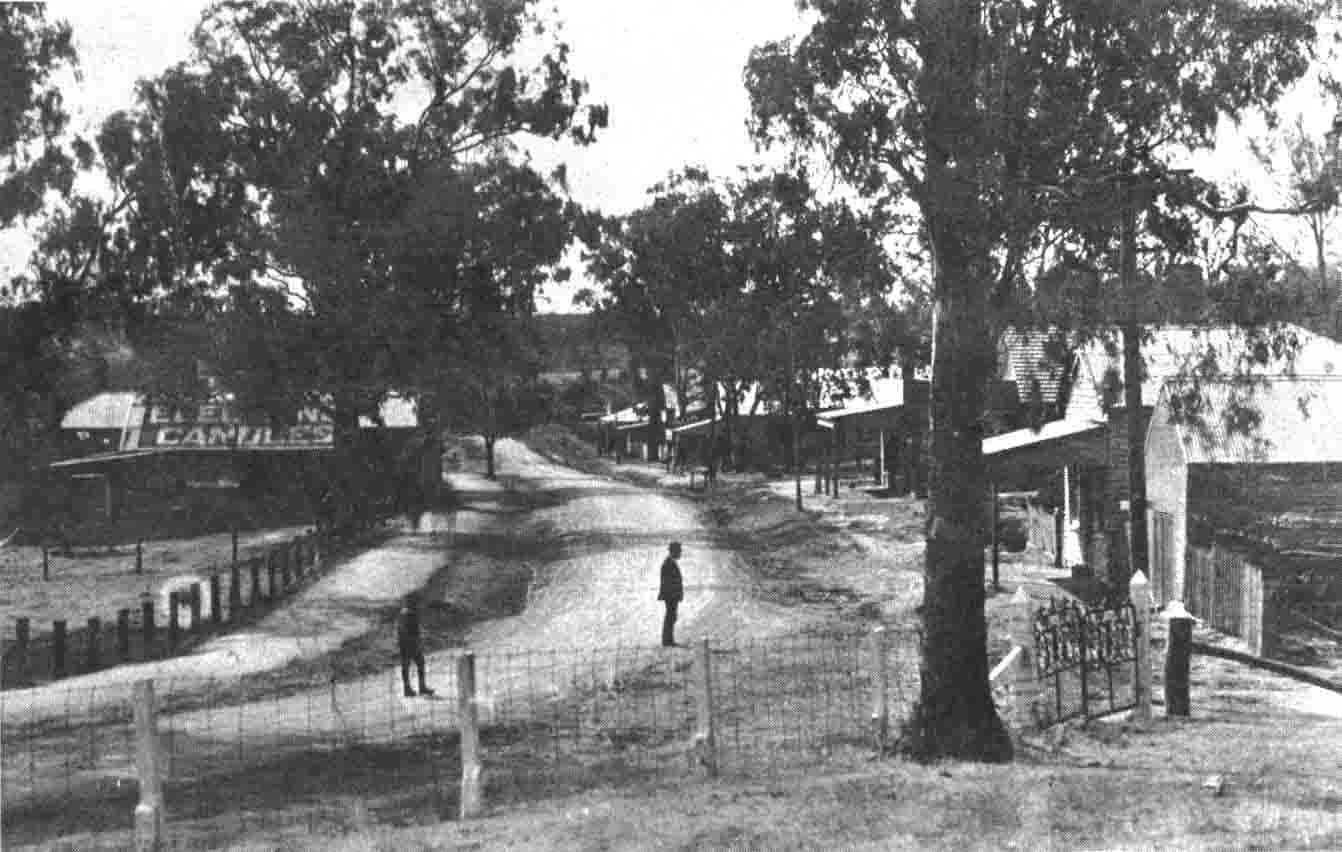

The main street of Eltham in about 1930

The main street of Eltham in about 1930

The township consisted of five shops, a railway station, a shire hall and a country fire station. A handful of wooden houses completed the scene, to give it a serenity and a silence that are no longer present. Among the special atmospheric factors indigenous to the valley were the wood fires. The smoke they emitted rose vertically from the chimneys in the winter mornings and evenings until it reached the surrounding hill tops. It then suddenly extended horizontally to provide a series of smoky stratas that were vaguely reminiscent of traditional Chinese mountain paintings, especially from the windows of our house which was high up on the eastern slopes. The occasional train, heard whistling as it approached the town before finally emerging through the mists, appeared to float on the ether as it came across the trestle bridge to the station. An occasional traditional goods train, drawn by a steam locomotive, would amble through and fill the valley with feathers of smoke that followed the rhythmic chuffing of its engine, leaving a whiff of coal fire in the listless air for the rest of the afternoon.

The danger of the emerging society in Australia was in its attitudes, Within a few years, we were to discover that nothing was sacred any more. The whole of the past was being offered up to placate this new god of progress and materialism. Melbourne, the most space-eating of all urban complexes with the exception of Los Angeles, expanded outwards at breakneck speed. Up to 1954, there was no real control of land use and no plan for the metropolis. The developers made the most of the opportunity.

Eltham was one of the few districts that retained a sense of personality in the midst of the amorphous growth. It did so largely because of the difficulty of developing the hills, creeks and bushland. These natural qualities were regarded by the suburban psyche as a hindrance. It was felt to be hillbilly and second-rate, compared with the market garden landscapes in the south-east of the city, where new streets were appearing every week. The hipped tile roof, set twenty-five foot from the frontage, was repeated through whole suburbs with religious fervour. The soils made for easy-growing lawns and beds of snapdragons and petunias.

This time of conformity could be traced to the increased opportunity for a much greater proportion of the population. Their first thoughts were to become as good as and as like everyone else as possible. Its one achievement was to produce Dame Edna Everage, that paragon of virtuous cliches and 'the most bonza Moonee Pondser of them all'.

Even the north end of the township tended to receive those who were not rich ,enough to get into the more expensive suburban syndrome, but the old Eltham did not change. It created a division within the town, as well as the division it experienced from surrounding districts. The local bush still had its ancient power to produce a united community. It may be harder to see it amongst the greatly increased population, and there are those who would sell it off and turn it into a suburb to make a profit out of it. It has always been threatened but never beaten. The battles fought for the native trees, which were then genuinely regarded as rubbish, has since borne good fruit. In the central riding, there are more than twice as many trees today as there were in 1945. Whole, open hillsides have been turned back into dense bushscapes, despite every development. There is scarcely a hilltop dominated by a building. The indigenous population and the trees grew side by side.

Eltham has produced men like Gordon Ford and Peter Glass, to name only two, who are among the rare breed of instinctive Australian landscape architects. They emerged imperceptibly to become vital influences in their profession and in Australia generally. There have always been plenty of imported landscapers, who learnt their profession overseas and who come to practise their well-intentioned principles on our countryside. The 'instinctives', on the other hand, are those who have become hooked on the Australian flora and find themselves getting deeper into its wonders and mysteries every year. They are totally non-exotic and totally unrepentant. They can ignore the finest trees from other countries because their eyes have seen the glory and they will never be satisfied with anything else again. They have discovered that the two will not mix, and that the great primeval reality of Australia must be accepted whole and without the addition of any imported flavours. This process is gradual rather than sudden. I know of no person other than myself who is over fifty years of age, interested in landscape and has never planted a pine tree. And the only reason I escaped was because I used to accompany my uncle, one of the later Australian impressionists, on his painting excursions. He would refer to the sour green of the pines and the disastrous effect they had on the light of the natural bush landscape, and I saw what he meant. Now, more than forty years later, there are groups of people who go around destroying pine trees for what their ubiquitous presence is doing to the colour and light of the landscape. It is by means of such eccentric minorities that the inner realities of the land are sustained.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >