Alternative Housing, In Search of Eldorado

In Search of Eldorado

Author: Alistair Knox

An attainable dream

IT did not immediately register that David and Helen Hyatt were candidates for the alternative lifestyle when they called at our office. They planned to bypass the cities and the false civilization which so many Australians have been 'duped' into.

They were living in the Melbourne suburb of Altona, which has changed its character since World War II from a quiet, southwestern fringe of the maritime industrial area of Williamstown and Newport into the centre of the city's heavy industry. Great cracking plants, carbon black chemical producers and other complexes proliferate the area. The many modern processes, that are using up natural resources at such an alarming rate, crowd on to each other and the small residential areas are wedged between them. The perpetual strange smells that the manufacturers generate are modern industry's substitute for the flavour of eucalypt and dogwood that once grew there. The whole district is now almost entirely paved or bitumened, and this further prevents the dark, sweet scent of the natural earth from reaching the nostrils - a requirement as needful to a complete man as his daily bread. Altona, through no fault of its own except that it was not regarded as a prime residential area, has become a victim of the 'progressive' society.

The Hyatts were both school teachers. They were buying land in Eldorado to share an alternative lifestyle with their friends, Esther and John Roodenberg. Their combined land comprised more than 200 acres of wide, high, unused farmland. It looked into the Woolshed Valley on one side and away over another enormous valley commanding a view of Mounts Buffalo, Hotham, Feathertop and Buller on the other. It all sounded as exciting to me as the prospect was to them.

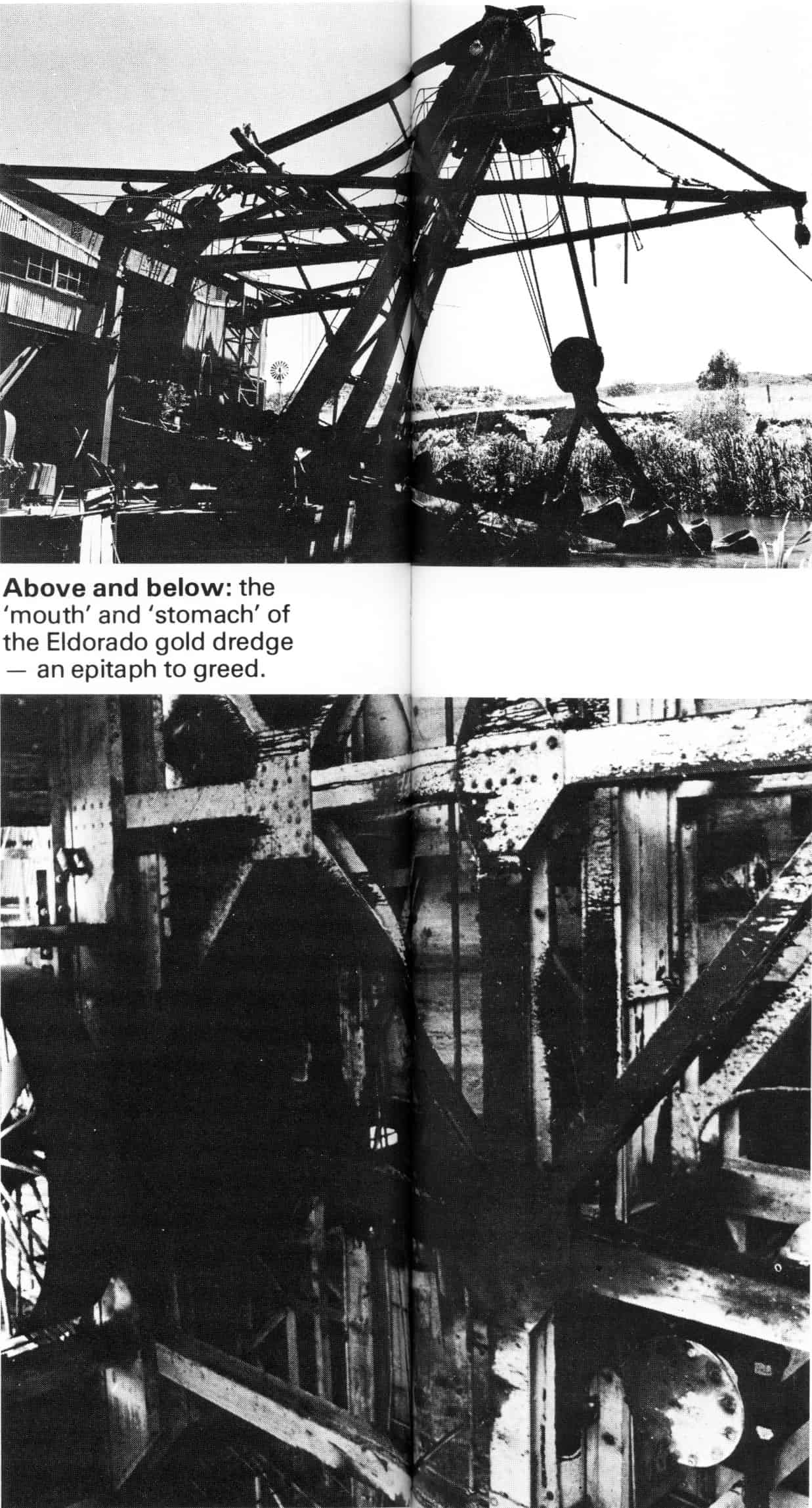

I had just resigned from the local council on account of the pressures it generated, and was not particularly stimulated by the thought of having to go to the north-east of the State the following Saturday. However, it is impossible to remain in a low mood for long as one drives in that direction in the early morning. The warm, gold sunlight, the purity of the air over the Dividing Range and the long line of high blue mountains in the distance create a climate of great wellbeing - a feeling of anticipation that the world is still limitless and full of infinite promise. The road narrows to a gravel track near Eldorado, an old gold-mining town. The wheels of the car crushed the dry gum leaves with a crisp, whispering sound that awakened recollections of boyhood nostalgia. An enormous gold-sluicing dredge had worked there for many years. All Victoria's gold-mining areas show the ravages of man when he butchered the previously untouched soil to find his specks of gold. And there is nothing that damages the landscape more permanently and broadly than dredging. The great machine, about 100 yards in length and proportioned to suit, creeps up the river, ejecting powerful jets .of water to make it into a formless wasteland. Today it still remains where it did its ugly work, deserted by its masters now that it is no longer a useful servant for their misguided gains. Plunder and pillage are not restricted' to the ancient Philistines or the hordes of Ghengis Khan. Modern society is still prepared to accept the destruction of landscape, the basis of all life, for the sake of shortsighted, immediate gain. It will never try to reinstate the environment unless it is forced to pay the true cost of its products.

Leaving the township behind us, we turned up a road that was predominantly forest with callitris and eucalypt that has some commercial value in its natural state. The general character of the bush became fairly hungry as we ascended the track that led to their gate. Their own land had been cleared to expose large clumps of weatherworn, granite boulders, piled on top of each other at the sum:iIlits of the rises that occurred every few hundred yards. When we arrived at John Roodenberg's first proposed house site, I was surprised to see it set out for a heated slab and boxed out ready to pour. A glance at his plan was very depressing. It was an economy-packaged job which a firm of builders had dreamed up to fulfil the short-term, low-cost needs of purchasers of limited means. Every mannerism of the past fifty years was represented. It was not that cheap either, but its cardinal fault was that it provided an unthinking answer. It provided no flicker of an alternative to the standards of buildings which would scarcely be contemplated even in today's Altona. I urged them to stop and think again, and invited them to our 'Earth Day' which we have on our property each November, to demonstrate the possibilities available to those who are prepared to step out and explore a true alternative lifestyle.

They both listened intently as I explained that it was poor economy and a misuse of the land, damage to which would take a generation to reverse. They put off the concrete pour and waited.

Our Earth Day turned out really wet. Steady rain set in just as people started to arrive. It got heavier until there were torrential spasms mixed with solid rain. Cars began to bank up the road adjacent to our property, until it was necessary to walk up to half a mile to reach the house. Some people even brought dogs on leashes in addition to their many children. The sheer quantity of water they brought in with them caused the floors to become awash, and streams of water actually flowed out the doors. Our house is slatepaved, brick-paved and, in a small section, planked with wide, jarrah boards. A large number of Margot's Persian rugs are in every room, and these also became saturated with water and mud. Fifteen hundred people attended during the day, despite the appalling conditions. They ferried each other up and down the road to their cars, and a great spirit of goodwill and co-operation prevailed.

When the last visitor had finally departed, we surveyed the situation. We were too tired for a clean-up that night, so I suggested we light some fires and go to bed. The following morning was Sunday, and I asked Margot to leave it all until I got back from church. I was amazed when I returned two hours later to find the whole flood had been cleaned up, carpets and all.

'Who came,' I asked, 'or what did you do?' Margot said she put our industrial polishing brush over slate, timber, brick and carpets without distinction. The heat had dried most of it up overnight. This was followed by the vacuum cleaner, and the job was done. It was amazing to see how resilient environmental building is to the most rigorous treatment.

Through all this, the Roodenbergs' eyes were really opened. John is a very careful person, with an organising Dutch streak, and he was quite convinced in the project. He was prepared to build on Hyatts' land rather than' his own as they were planning a joint house, and I suggested David's site was preferable to his. They commissioned me to start designing a house with common living areas and separate bedroom wings. They were a group of practising Christians who hoped that others with needs would come and join them. They did not regard their house as their own, so much as a trust which they were privileged to administer. It was wonderfully refreshing to see their attitude to it all.

The first design was fairly ambitious with a two-storied bedroom complex on either side of the common central living wing, encompassing a meeting room thirty-six by twenty-four feet. A gallery over part of it was entered from both bedroom wings, but it was not accessible from the central room. It gave the personal bedroom wings some control over the common living centre. The owners could communicate easily, while guests and casuals remained below. They eventually rejected this concept in favour of a similar plan, but without the upper levels. The house was still fairly tall. It was as usual designed around heavy corner posts and solid window frames of six by three inches throughout. The roof members were point loaded on to these supports, and the whole building could be stood up and roofed if necessary, before any mud bricks were laid at all. The chimneys were large and to be built in earth also, except for pressed brick linings. The great advantage of the post and frame structure is the confidence it gives in seeing the building standing before the mud bricks are sighted. Its disadvantage is the slight shrinking in wall height which takes place. Due to the mortar, the walls require going over again when they are dry.

I visited Eldorado a few months later to find things well under way. The initial purpose of the visit was to see their next-door neighbours. Here again there were two couples who had 300 acres between them. They were to have two separate houses and we were planning the second of them.

I took Rob Boyle, the young and talented landscape designer, with me for company to have a look around. We missed the turnoff to the Hyatt-Roodenberg property because Rob was driving and didn't know what to look for. When I realized something had happened a little further on, we got through another opening and started cutting across the undulating countryside. 'It is somewhere on that hill', I kept saying. Each time we went in that direction for a few hundred yards, we would find ourselves tottering over one of the heaped up boulder mounds with a twenty foot drop below us. Finally John Roodenberg spotted us. He went into their temporary shelter and emerged with a bugle, from which he squeezed untuneful and hideous blasts, either to attract us or encourage our progress. No doubt Joshua's trumpets sounded much the same to the people of Jericho.

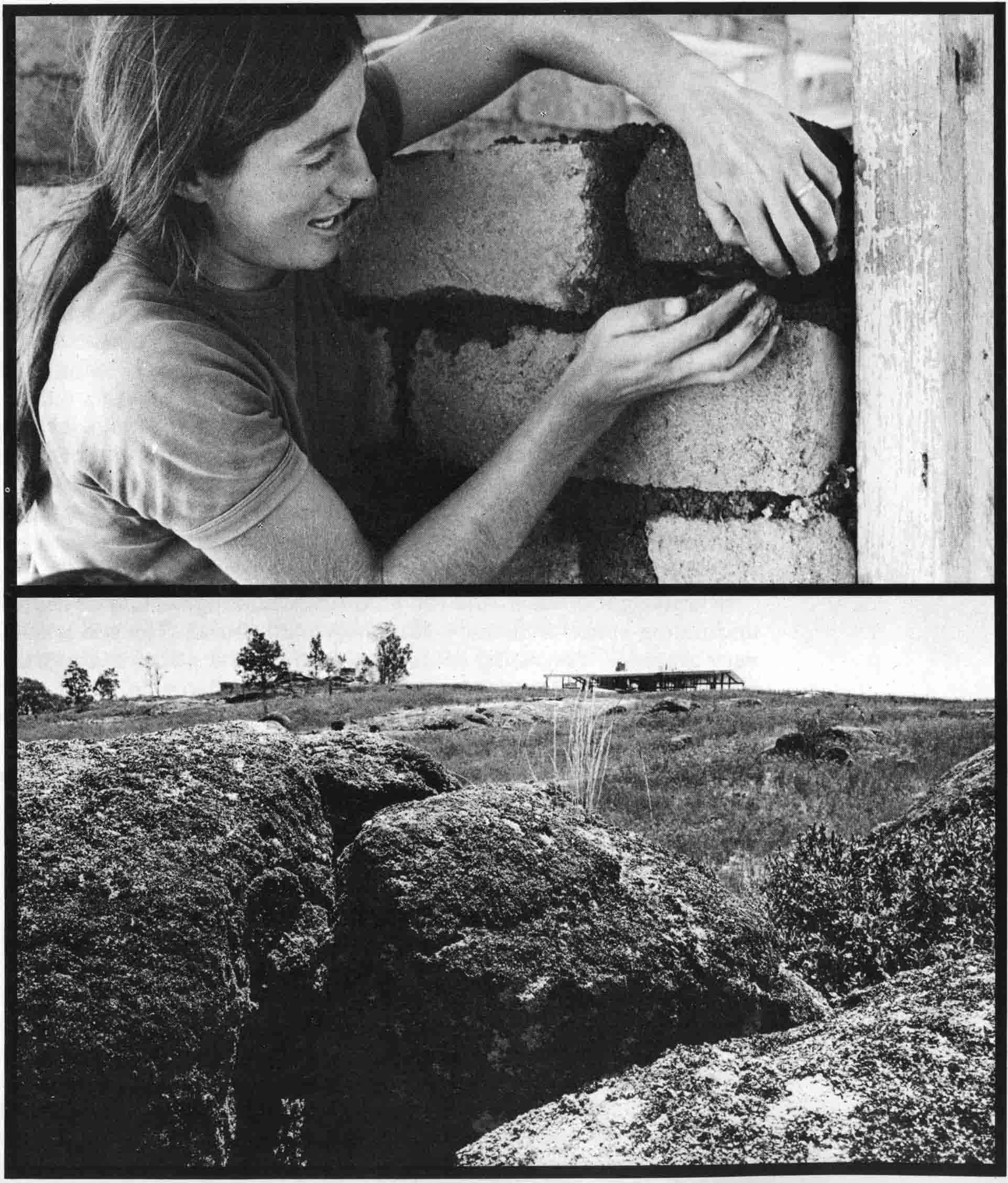

We could see him, but between us was a great gulf fixed through which no man seemed able to pass. By slow degrees and with some damage to the car, by riding over some fences and getting under others, we found the track that led us to them. We went straight to the Hardhams, our clients next-door, and talked to them for an hour or so. I worked out preliminary ideas and returned to the Hyatts and Roodenbergs. They were living in a farm shed and an adjacent, hut-like structure, but they had a spring water supply and a bath! They were bursting with happiness and action, especially the girls. Helen and Esther were driving the tractor and using the blade to turn over their mud-brick mix. Around them lay a great sea of bricks already formed which were drying in the sun. Helen's slightly pale Altona complexion had been changed into one of glowing health. Esther, who had been living there longer, already had the ultimate in complexions. All their husbands could say from the other side of the shed was 'Aren't they marvellous?' They certainly were.

Above top Helen Hyatt at work - the mud brick infilling process underway. Above bottom The Eldorado homestead and the granite boulder landscape

Above top Helen Hyatt at work - the mud brick infilling process underway. Above bottom The Eldorado homestead and the granite boulder landscape

It was a good, clean site for mud-brick making - lots of slightly undulating space with marvellous views all round. The soil was very granular, consisting of decomposed granite pieces averaging about one-eighth to one-quarter of an inch in diameter. Most of the rest of the soil was sandy, but they managed to get about 20 % of clay into it as well. It formed up into quite a solid brick. I had used granite topsoils in the Tarangulla-Murphy's Creek area twenty-five years earlier, but in that instance the particles of granite were smaller and more like a gritty topsoil. This material was similar to one-quarter of an inch crushed rock and dust.

It is sometimes still something of a mystery how some soils stick together to make bricks as well as they do. It provides a degree of justification for the eternal question that Western society will ask about them till the end of time: 'Why don't they melt in the rain?' The structure of nature is as mysterious as life itself, if only because it is part of that life and clay, loam and water are the basic constituents of the earth's crust.

This is the prime reason why mud-brick and other earth walls are so satisfying to live in. They look human in texture and, in my opinion, should be finished so that they resemble the character of the back of one's hand. After living in our present earth building for some twelve years, after we had opened the house for the hundredth time for some performance, my wife Margot remarked that she still only partly understood the power and inspiration of earth building on the unconscious life of its inhabitants.

The bricks that the girls made formed up and slipped out of the mould easily because of the low clay content. Had they been mostly clay, they would probably have had to be cut out by going around the mould with a brick trowel, to relieve the adhering properties of the compressed clay.

On our journey from Melbourne to Eldorado, we gave a lift to two hitchhikers who were heading for Beechworth. The girl was Scottish and her husband Canadian. I suggested they might like to deviate and see our project, and that we would drop them at Beechworth which we proposed to visit in the evening. The man seemed a little hesitant, as if we were contemplating murdering them for their swags. The girl was more confident they would survive, so they stayed with the Hyatts and Roodenbergs while we went next door to the Hardhams. When we returned, the Canadian had formed a few bricks and, for a time, I thought he would conclude his travels there and then and start building for himself.

We left when the winter sun was well down on the horizon. We intended to look at the potter John Dermer's house at Yackandandah at about sunset. It was fifteen miles further on. I had wanted to set eyes on this structure for some time. John had been a designer at Josiah Wedgwood and other famous potteries overseas. He came back to live in Eltham for some time, then he bought forty acres at Yackandandah, a beautiful little town with this far-away name on the north-east of Victoria. He had a pottery and house designed by Robert Marshall on a hill outside the town, on which he and his wife set about building on their own. Yackandandah is part of Aldonga, the Albury-Wodonga complex, which is the second inland city being built in Australia between Sydney and Melbourne. These major urban complexes are about 600 miles apart. Aldonga is 200 miles from Melbourne, and Canberra (the Australian capital) is 200 miles from Sydney. The two new cities are therefore 200 miles from each other. It would be difficult to find a better place to build a new town with an anticipated population of up to, say, 200,000. The climate is good, the country itself beautiful and hilly. The land is well-watered and prosperous, with all the essential ingredients of an impressionist painter's landscape of colour and light.

Eldorado is closely related in character to Aldonga and very much part of the same twelve-month sunny climate. As we passed along gravel roads from the Hyatts and Roodenbergs, the late sun intensified its gold-red light for which the Australian landscape is famous. The colour became continually stronger and darker as it touched the horizon. The hill we were heading for turned from pink to terracotta to crimson. In a disappearing flurry, it turned magenta and sped up the hillside close to us in a retreating wave at about thirty miles an hour. The contrast between the light and the evening was a clearly defined line and we suddenly became aware of the frosty atmosphere and the cold. The long visibility remained, but the scene was now blue-white. The Dermer house and pottery were two separate buildings, each twelve-sided figures with an interesting clerestory section above the central core of the buildings. John Dermer is a strong and direct man. Large posts were as usual the main supports for the buildings, with mud-brick walls between.

He had hewn the required number of them from the nearby forest and stood them up single-handed. They were hardwood and of very substantial diameter. Their dead weight must have been great, but somehow they were manhandled into position. It was a superb effort for this exponent of the, alternative society. He lives entirely from his pottery exhibitions and, when we saw the great kiln he had built in the pottery, we were impressed beyond measure at his ability and productivity. People with artistic talent are nearly always very practical builders. Few were more so than John. If the alternative society is to arrive in Australia, it will be done by flesh-and-blood people ranging from school teachers to bank managers, potters to porters who are prepared to buck the system like the Hyatts, the Roodenbergs and the Dermers. None of them expect the way to be as easy as doing a nine-to-five job until retirement, whether in a treeless street in Altona or on a building block in Eltham. But they will have retained in their hearts 'the vision splendid' of a return to the challenging liberty of their pioneer forefathers.

I again called on the Hyatt-Roodenberg job about six months later. We had, in the meantime, met a couple of times in Melbourne in search of materials. On one occasion we went to the Electricity Commission's depot at Doncaster, a suburb adjacent to Eltham, but on the other side of the Yarra River. As we stood looking at a heap of about sixty hardwood light poles, comparatively new and all dressed into hexagonal shapes, I was reminded how the river had divided Melbourne into the eastern suburbs on the one side and the rest on the other. Perhaps it was the quality of the poles they were selling. Had they been in one of the northern suburbs they would have been much older and more weatherworn.

When Melbourne was a large parochial village of one million or less, there were real-estate advantages in the demarcation the river provided. But by the seventies practically all the orchards of the German pioneers who had originally settled the area had been subdivided into residential allotments. As the land has an easy terrain and was cleared except for the low-growing fruit trees, its development made the real-estate agents' hearts quiver with anticipation as they mentally calculated the geometrical progression of prices as each orchard was demolished. The district greatly attracted the young executives during the sixties when they believed the growth economy was as eternal as the stars. They kept building bigger and more blatant houses which, from a distance, seemed to coagulate and blend into a great open sore exposed on the dying body of the countryside. Its natural, pleasant landscape disappeared even more quickly than the price for the land had risen.

The psychological centre of Doncaster had always been White's Corner, an ambitious outpost of development constructed just prior to the great land boom of the late nineteenth century. It was a cardinal landmark in the eastern suburban Melbournians' mind. It stood isolated on a hill surrounded by silent paddocks and could be seen for several miles in every direction. Its ugly square form of red bricks became the ultima Thule of the townscape. Beyond it lay the mild pink colour and light of the Yarra Valley bushland, with the backdrop of the dark blue Dandenongs beyond.

We negotiated the poles purchase and divided the spoils. The yard foreman had a Scottish accent and was still evincing a sense of national surprise punctuated with various 'ayes' and 'ahs', that an odd material like reclaimed light poles could suddenly become an object of desire in such a well-behaved and elegant place. I felt he finally discounted our carefully controlled interest in them by deciding we were really only hippies after all, dressed in suburban clothing, who had never enjoyed the delights of Doncaster Shopping Town. That multi-storied complex now sits on the identical site that was occupied by the erstwhile White's Corner. Instead of being the ultima Thule of the town, it was now a vantage point from which the ever-radiating rings of the outer suburbs could be evaluated. No doubt the foreman had forsaken his own wild Caledonian heritage for the unctuous delights of that bizarre commercial edifice, so successful in its contrivance of every architectural cliche without conceding one interesting feature.

The smells of microwave cooking of waffles and donuts and the scent of jelly beans and fruit jubes have always had a paralysing effect on the will of the nine-to-five workforce.

But back in Eldorado these considerations meant nothing at all. It was a hot summer's day when we turned up the forest road. We could see the house on the top of its hill half a mile to the west. The Doncaster light poles had all been erected and were supporting the roof and some brick chimneys (now changed from mud into pressed brick), with mud infill walls partly completed. But the district was again determined that the city interlopers should not gain access to its privacy without a battle. Deciding we had again missed the turn-off, I started to turn the car around by backing and filling on the hard strong gravel surface. Without warning the front-wheel-drive vehicle spun its wheels up to the axles in the decomposed gravel surface. I had taken a photographer with me to record developments. We climbed out and jacked up one wheel and pushed branches into the hole the wheel had cut. Just then the bricklayers, who had seen our dilemma from the hill, approached to tow us out. We decided we could lift the other wheel, which we did, and immediately the car started to roll off down the steep decline ... almost into a tree. I had visions of a greater debacle than on our first visit. It was all worthwhile however when we clapped eyes on Esther Roodenberg and Helen Hyatt. They were a reincarnation of the female lifestyle that had occurred in Eltham thirty years earlier, when the mud-brick movement first got underway.

The first impact when you saw them was the sense of assurance and power they radiated. The second was an aura of health and happiness. Both wore only shorts and singlets and their faces, bodies and clothing were equally dusted all over with what appeared to be brown powder. This almost gossamer veil character was the dust of mud bricks that covered them from head to toe. They were a joint command in control of all proceedings. They rapidly sketched out activities that had occurred to date as we walked from their temporary living quarters to the new building. The picture of the finished building was firmly in their minds the way it has to be in the imagination of every true builder: 'The first morning of creation wrote what the last day of reckoning would be'.

The finest quality that marks the alternative lifestyle builder is that his course is set like that of a wise mariner. He knows where he is going. Storms and problems will arise in the course of the voyage, but provision is made for them in advance. There is that sense of constructive intuition in the work that can be observed in nature - the sense of resilience in a concept that adjusts to circumstance without losing purpose. It was fascinating to discover their bricks had exceptional crushing strength (about 700 lbs to the square inch). They told me they had tried breaking some by throwing them about and they were not able to do so. The combination of the gritty granite gravel and the dust had formed into a kind of mild concrete that was quite remarkable. It was a great experience to stand in the building with the main roof cover completed, and look out between the poles down into the Woodshed Valley on one side towards the mountain ranges, far away across the long valley, on the other. It held a clear open view, with only occasional farm houses in the vast distances, creating a sensation of being almost alone in a supreme landscape.

The bricklayer who was building the fireplace was assisted by a nearby farmer, exchanging his labour for work the girls had done carting in his wheat harvest a little earlier. The obvious admiration both men had for the girls' abilities didn't do any harm either. The mutual respect all-round made for concentrated effort which could make the job literally zing along.

Esther's two young children were as busy as everyone else. The three-year-old daughter was up the ladder beside her mother and her two-year-old brother was wheeling a child's wheelbarrow around, complete with shover and a deep, concentrated look as if they had been doing it for year. Even at that early age they were imbibing the basic attitude to building that the alternative lifestyle requires: sound construction and an economical use of materials under the control of ordinary people. The expert was nowhere to be seen.

Every day we see further evidence of how the accepted attitudes of the technical method is wrecking our civilisation. The ordinary person is so often intimidated into giving up trying to do it for himself and this capitulation makes him a slave of the experts of life. Nearly all technical benefits are suspect, especially those relating to food and health. Modern medicine is never happier than when injecting dubious chemicals into unresisting bodies of patients

or prescribing cure-all pills that can subsequently prove lethal. Modern food processing has caused a serious decline in the quality of all we eat. Many people have so little respect for their minds and bodies that they would rather trust it to someone else than themselves. Not even vitamin pills are needed in the Eldorado environment. It is simply breathing the pure air, doing the hard work and enjoying a life that makes the total person fulfilled and fit. Looking out over the immense panorama I recollected how in ancient times people could live so much better and more varied lives than we do today. Take the case of Moses. For forty years he lived in the king's palace. For forty years he was a shepherd in the desert. For forty years he led the complaining, arguing and disobedient Hebrews to the promised land. When he finally handed over to Joshua to take them over the Jordan, it was written to him: 'Moses was an hundred and twenty years old when he died; his eye was not dim nor his natural force abated'.

We had to leave after only a short stay because we had spent an hour looking over the great gold dredge back in Eldorado that I merely glimpsed on previous visits.

It is not easy to find a greater contrast between the inherent worth of the Hyatt-Roodenberg venture and the ambitious uselessness of the Eldorado dredge. For twelve years the great endless chain of dredging buckets ruthlessly cut up the valley, working non-stop day and night in the search for gold. The now silent conglomeration of rusting boiler plate, galvanised iron and gears is an appropriate symbol of the efforts mankind puts into gaining useless materials when he could be enjoying a total life. The end result of his efforts is a totally-destroyed landscape and some gold which either finishes up in a bank vault, as a piece of jewellery or as some item like the Melbourne Cup.

We talked about the dredge over lunch. One of the girls mentioned there were once forty shops in Eldorado, where now there was practically none. Even the rather substantial school was no longer used for its original purpose. Instead it housed the historical relics of a dying township.

'I suppose it was good for everyone while it lasted', commented Esther. I felt that it was little better than wanton vandalism because of the trail of destruction it left behind. Worse still, it has helped supply the means of maintaining a system of finance that has been the perpetual plague of Western democracies, with millions being controlled by the few.

As we returned to Melbourne, my passenger and I were both aware we were leaving something very special behind that made us vaguely melancholy. But the speeding cars on the MelbourneSydney freeway, and the diesel trains that ran nearby, soon took away our sense of disengagement from our surroundings. Life once more, became a struggle for survival in the urban frenzy. In some way an impact must be made on the wills of those who haven't the privilege of visiting such remote places on quiet weekdays, to put aside for a time the world of the city.

Sequel

Just as we were leaving the house to have a look at the gold dredge, Helen quietly told me that she and David were not going to continue in their joint venture with the Roodenbergs. I was most surprised - they seemed to be getting on in such accord. 'I'm ready for it,' she said, 'but David isn't'. As I had written most of the Eldorado chapter at that time, I knew it would be necessary to return to find out what the outcome of her remarks would make on the final story. I made a day to visit Esther and John in ten months' time.

It was quite a journey through Healesville to Eldorado. It included some marvellous landscape on the Black Spur. Great sections of the forest consist entirely of mountain ash, growing up straight and branchless to towering heights. The ribbon-like bark they continually shed from their slim, perfectly vertical trunks hangs down like long, brown vines. Although they grow so close together, the sun still strikes through the trunks and the tree ferns on to the forest floor, creating a strange spirit of unearthliness in the patchwork of light and shadow below. The pale, cream trunks in some ways are like collosal blades of grass over 100 feet high. One could imagine the Creator experimenting with a universe on an entirely different scale to the one we normally inhabit. The extraordinary regularity of shape and height of the mountain ash is in part due to the fact that the entire area was burnt out by bush fires in 1939, when one-tenth of Victoria was on fire during a terrible week in January. Was it any wonder that the smoke from the conflagration was visible in South America on the other side of the Pacific? It generates a sense of humility and awe to meditate again on the power and dimension of the Australian continent.

The weather was as beautiful as ever as I ascended the Roodenberg hill and looked out over the sweeping landscape. My first view of the building reconfirmed my sense of its appropriateness to the world around it. It reflected a summation of all the surrounding land shapes, as if it had always been a part of the environment. There was some building clutter stacked here and there that always accompanies partly completed houses already lived in. I discovered a further reason when I set eyes on Esther Roodenberg. She was close to an increase in her family, but it did not prevent her standing on a ladder to stain some upper cupboard doors in the bathroom. The children, both appreciably bigger than when I last saw them, greeted me with obvious enthusiasm. My heart reached out to them. What opportunities await them in childhood! They had the very best of life ahead of them, with parents that exercise a careful balance between patience and authority and an expansive natural environment surrounding them. The Roodenbergs were consciously pleased that the children could ride around the generous living room on their tricycles without doing damage to precious, cluttering possessions. They all enjoyed a high degree of relaxation and calm, as well as intimacy, as a family.

We discussed the problem of the departure of the Hyatts, as the sunset coloured the hills and valleys around us. The immense vistas revealed a couple of vertical columns of smoke, pin-pointing burning-off activities in the otherwise silent scene. There was no hum of distant cars, planes or any other impediments of civilization. We were alone with nature. Esther's explanation was simple. They had differed with the Hyatts as to the ultimate goal of the building project. For the Hyatts it was a ten-year program that was partly an end in itself. For Esther and John it was a means to an end. Their objective reasoning saw the lifestyle as a manifestation of their beliefs to for:m a Christian community without delay. They did not intend going off on interesting excursions for weekends and holidays, while allowing the building to drag on to a slow, casual conclusion. The Hyatts on the other hand had no family and were less obligated to daily circumstance than Esther and John. There were differing degrees of commitment to the concept and differing levels of need. The 'division' caused no bitterness on either side. Today the Hyatts are again building near Ballarat and Helen is expecting her first child. I am confident that she, like Esther, is still pressing on with the structural work.

As the evening imperceptibly closed over us and the luminous stars became visible through the clerestory windows, John projected some slides of the actual building work. We recalled the various stages of construction and the various tasks accompanying them, such as the girls mixing the earth with the Ferguson tractor and laying brick on brick, using the same gritty topsoil for mortar as that which formed the bricks. Not only do we learn through doing; we also lay down a pattern for health, longevity and harmony that develops the whole man and woman.

Whilst I was sympathetic with the Hyatts' idea of taking things steadily, I responded more to the vigour and vision of Esther and John. I understand that another family now intends to join them. They will build on the property, though not live in the same building.

There are many potential setbacks in the alternative lifestyle. Adjustments will always need to be made. It is not the easy matter some well-intentioned people feel it should be. A number of models are available to those who would live in community. I believe that a group of ten, twelve or more families can have a community kitchen and eat together - probably easier than if there are only four. Community living is even more attractive when most of the couples have young children. This gives greater freedom to all and creates an instant, extended family into which the young can grow up and experience to the full their childhood and youth. I have slowly come to the conclusion, through having my own mother living with us until she died at ninety, as well as Margot's mother (still enjoying good health in her eighties), in the veracity of the extended family system. A good case can be made out for 'adopting' a suitable grandmother or grandfather, if you can afford it and you haven't a survivor of your own.

The children love to go over and watch television, and have those cups of tea and toast that taste so much nicer than in their own kitchens. They will recollect these social experiences long after they have grown up and left home. In the frantic life of modern suburbia children, by their isolation, can find themselves in an alliance against the father and mother of the household. In the alternative lifestyle however, there is a balance between time and events which makes for sensible living and perspective, rhythms of socialisation which maximise the best of life from the cradle to the grave. To live like the Roodenbergs is to find indeed the true Eldorado.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >