We Are What We Stand On, The Dunmoochin Potters

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

The Dunmoochin Potters

Author: Alistair Knox

It was ten years after Clif first settled in Dunmoochin that Peter and Helen Laycock moved in to begin a potters community within the artists' enclave. Two years earlier, they had gone to live at Strathewen and had known Clif, Marlene, Alma and some of the others for years.

Strathewen is situated on the western edge of Eltham's hills, valleys and secret places. It has a very settled landscape that has changed little in a hundred years. It embraces the valley of the Arthurs Creek, close to where the surrounding hills climb up to form the Kinglake mountains. They, in turn, are part of the serpentine tail of the Great Dividing Range that extends in an unbroken line from the top of Australia two thousand miles to the north.

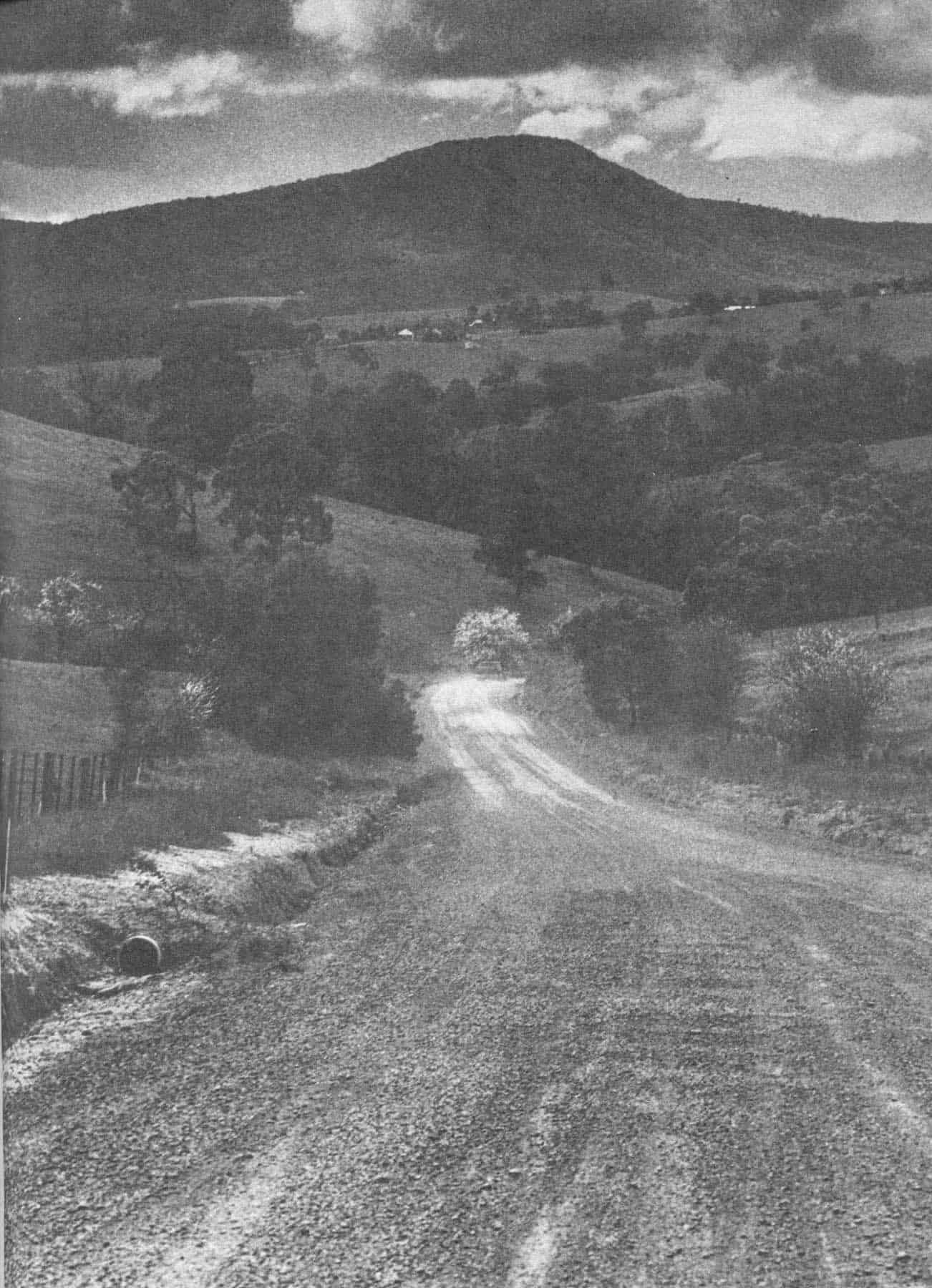

Mount Sugarloaf dominate the Arthurs Creek Road

Mount Sugarloaf dominate the Arthurs Creek Road

The sheep and cattle that graze on the flood plains of the Arthur's Creek and the great orchards and vineyards which grow on either side of the road that leads to the precipitous track to the top of the range, has changed the inner landscape into a semi-European rural scene.

The Arthur's Creek Road passes the entry to Dunmoochin, close to the top of the hill that provides the first spectacular glimpse into its high swelling hills and darkly-treed valleys. Mt. Sugarloaf, which is only a distant feature in the Kinglake Range when viewed from Central Eltham, stands close and dominating to the north. Further west, the farmland pattern can be observed merging into a limitless plain. Only Mt. Macedon appears to offer a barrier to the hazy sunlit flatness, which eventually dissolves into the great Australian central wilderness. At certain points along the Strathewen road it is possible to grasp some sense of this landscape stretching 2,000 miles to the north and 2,000 thousand miles to the west. It is a profound vision.

There is a sense of elation in its unfrequented savannahs, a well spring of wonder and poetry to the creative minds that were being drawn to become part of Dunmoochin. Money was still their least available commodity; ingenuity and improvization their most abundant. They found some good pottery clay while they were making mud bricks in Alma Shanahan's valley. Helen and Marlene started building up pots by hand. At some stage a very simple shed, consisting of an iron roof and a few supporting posts had been erected on John Perceval's land and Larry Stevens made a very primitive kick wheel. It had a concrete fly wheel and was a rather formidable opponent for any potter. It was said to make some of the beginners cry, but Peter Laycock claimed it was a good basic training for those intending to take up pottery seriously.

They found a professional builder of baker's ovens to erect a kiln with some fire bricks donated by John Perceval. All the intending potters contributed a few pounds to its cost and also provided labourers to assist in the work. Clif had become anxious to foster a pottery group to add to the ongoing character of the community. Helen Laycock was still making pots by hand because it was before her children had started school and her husband, Peter, had become interested in firing. He stated recently that he would never had been a potter if it had not been for ClifPugh's persuasive tactics. He sold them a piece of land on the condition that they started a pottery. They accepted his offer and set to work in the existing building and at the same time filled in the walls with mud bricks.

Peter Laycock gleaned information from Arthur Boyd, John Perceval and Neil Douglas and started production with hit-and-miss methods. He turned to stoneware because Alma Shanahan was also establishing her own workshop attached to her house and was using the natural Dunmoochin clay.

Pottery classes were held on Saturday afternoons. Peter was also a very good lecturer and he had an average attendance of about ten each week. It stimulated an ambition in those who were determined to become productive potters and also an appreciation of pottery in those who found it too difficult to set up potteries of their own. Bruce Davidson was next to arrive. He started as a student and became really involved and set up his own independent workshop. Peter Wiseman and his wife, Chris, attracted by the pottery climate, joined in the Dunmoochin group. Chris was a very good potter. She is now separated from her husband and works successfully under her maiden name.

Peter and Helen moved from the original pottery to where they were living. Bruce Davidson leased some of Myra Skipper's land and he and his brother, Jack, who also arrived as a learner, started working there. It was rather like a game of Ludo, with continual fluctuations of players and positions.

As new starters kept arriving and moving from place to place, Geoff Davidson (no relation to the other Davidson's) became a student with Robert Mair, who set up an independent pottery. He, himself, had been a student of Les Blakeborough at Mittagong. Names and faces continued to proliferate. Stella Saper and at a later date, Leon Saper, Sid Cairns, who now has his own pottery at Merricks North, were among his students. Quite recently, Clifs son Dylan and a girl named Jan Wardrop began a workshop at Bruce Davidson's.

I obtained this information from Helen Laycock one afternoon sitting outside the original house that Freddie and Verna Jacka built in the pre-1950 community that started on the west side of Bolton Street in conjunction with

Tim and Betty Burstall and others. 'It was amazing', she said, 'how it all grew'. Potters are rather like farmers and because of their heavy specialized equipment they tend to become tied to their land and form a solid base for a community. It's quite surprising that the number of potters is still as large as it is today.

Most of the clay in the earlier times came from the Kangaroo Ground sandpits that used to belong to the Graham Bros., who washed it in great antediluvian machines. Those operations created caves and sandpits that have always fascinated the potters and others who have known this area. Helen's strong, even-featured face, surrounded by her beautiful blonde-grey hair, looked ecstatic as she recalled it. It is now the Eltham tip and some of these pits are being filled in. 'I love the tip', she said with emotion. The marvellous colour and moonscape character of the land'. I know and feel exactly what she means. It has a mystery and enchantment. When I was a member of the Eltham council, I once went with John Mills, an Eltham potter, to see how we could keep some of it, especially where the washed clay was so good for pottery. He wanted to set up a school there in the great opensided steel and iron shed, but so many obstacles appeared that it frustrated our intention.

In the 1960's there were Sunday afternoon pottery exhibitions at Dunmoochin that were open to all. Invitations were sent out and it was an opportunity for local, interstate and international visitors to purchase examples of the work and enjoy a drink. It was held on the first Sunday of each month and became very popular with up to 500 attending at a time. It finally terminated because it was felt to have fulfilled its purpose and also because it got caught up in one of those periodical campaigns against Sunday drinking and driving. And where else could there be such a hotbed of danger and decadence as at an Artists' Colony, where the inhabitants seemed to enjoy community life and survive without setting off to a fixed job in the city every day?

Leon Saper became a successful potter after a prolonged evolutionary association with Dunmoochin. He first came to hear of its existence through Frank Werther whom he met in 1949 within weeks of his arrival in Australia from Europe because they were both members of the Y.M.C.A. Athletic Club. Most of the potters did not become full members of Dunmoochin Artists' Society although they lived within its geographical borders. Leon, however, joined in 1955 largely because his wife Stella was a full-time painter, which was originally the basic eligibility requirement for membership. Leon had had a very difficult life in Europe during the war. He had originally trained as a fitter and turner and it was his ambition to be an outstanding tradesman. At the completion of his apprenticeship, he intended to take his bag on his back and work his way through as many workshops in the country as he could. He was to stay away for many years and finally return as an incredible tradesman. When he arrived in Australia, a land of the free, he was convinced he could not help being wonderfully happy after the dark war years in Europe. He obtained a job at General Motors Holden as a maintenance man and set about to demonstrate his skills and abilities. No matter how hard he tried and what beautiful work he did, no-one seemed to take the slightest notice. He began to realize that his happiness in Australia was only relative. It was not a fulfilling life. He had, in the meantime, bought a house at Hawthorn and the thought of being incarcerated in G.M.H. for half his life to pay for it terrified him. He would sometimes rise very early and set off for Dunmoochin instead of going to G.M.H. to get away from his sense of despair. He had discovered what he didn't want, rather than what he did. It eventually caused a separation between his wife, Stella, and himself. She went to live in Jerusalem, where she became a very successful painter, but he remained in Australia because he found it impossible to keep away from the Dunmoochin bushland. He tried becoming a professional guitarist and attending the George Bell painting school, but these activities did not fulfil him either. He came to know Ruth, his present wife in 1968 when she started to do pottery with Robert Mair on 'Perceval's land', but their potterapprentice relationship failed completely. Some years earlier, Buster Hogan had helped him to throw a pot by holding his hands on the wheel. When he saw Peter Laycock and Peter Wiseman working at the top of the Laycock hill, he thought it may be possible for him to become a potter also. He had two short periods with Robert Mair and set himself up and has been making beautiful pottery ever since.

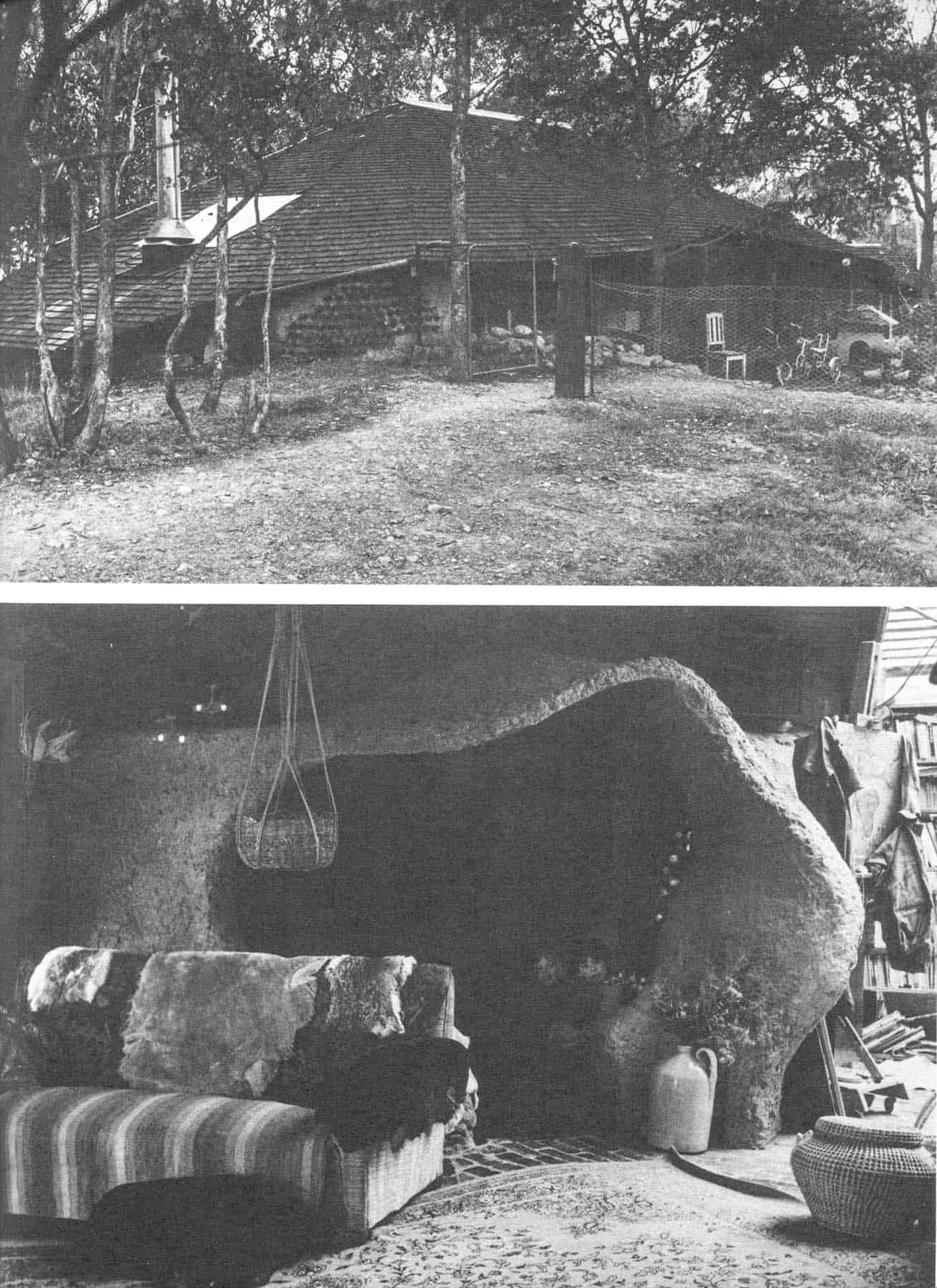

Leon Saper house created by Morrie Shaw: Above top:An exterior view.

Above bottom: An interior view showing some of the coral-like cavity divisions

Leon Saper house created by Morrie Shaw: Above top:An exterior view.

Above bottom: An interior view showing some of the coral-like cavity divisions

His first house at Dunmoochin was burnt down in 1960. He had erected a small building after the 1960 fire, which he used for about ten years. He then spoke to Maurice Shaw, who was training as an architect, to see how best he could make a few simple additions to it. Maurice Shaw quickly became interested in what to him was a strange mud brick medium. He persuaded Saper to erect a new building and leave the design and structure to him, except to state that he Leon preferred round and curving shapes to rectangles. Shaw responded by producing one of the most amazing designs that have occurred in mud brick building. It has been equalled only by Macgregor Knox's extension to the J ackson hou~e in Eltham and perhaps a few that we have done over the years. It consisted of two circles that fuse into each other, with each circle being supported from its centre by a system of radiating rafters.

The building is sited in the primitive Dunmoochin landscape and this spirit of the land is repeated inside. In some parts the wood shingle roof line comes to within two feet of the higher part of irregular land shape surrounding the house. From the front entry the floor rises into a mound between one and two feet in height, so that most of the floor is sloping from the central higher point. The flooring is of brick. A substantial section of the ceiling is glass. In summer conditions, canvas screens are fitted under these sections to protect them from too much direct sunlight. The glass is made secure by a series of battens running over the rafters onto which the glass is laid and fixed so that it is waterproof. The division between the internal uses of the house consists of three organic and free standing shapes made from mud brick material, supported by concrete reinforcing steel. The effect is quite remarkable and rugged. The containing shapes have an underwater character like coral cavities. They contain a bathroom, a fireplace area on one side of it and sitting and reclining areas on the other. The remaining shape is a bedroom. The fireplace enclosure had its free organic spirit carried further by a bulging wall consisting mainly of wine bottles placed close together in an end-on position and pressed through the mud walls. Maurice Shaw must have had a lot of mind-developing fun doing it all. He used to call at my house sometimes around this period and talk to me about it, but I never saw it until it was finished and he had left for the United States. We used to hear that he was on the threshold of big things, but it appeared that the work permits and the life precluded him from making a top line position, that I believe he could have occupied in other circumstances. He returned to Australia some years later and he has recently been designing imaginative children's playgrounds and adventure places in Glebe in inner Sydney. Maurie Shaw was an exciting man and there is no doubt that his association with the Dunmoochin Artists' Colony has been instrumental in developing his natural potentials.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >