We Are What We Stand On, Professional mud brick building

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

Professional mud brick building

Author: Alistair Knox

I was in a semi-amateur role at the bank which had not stopped contributing my weekly salary and affording plenty of blotting paper on which to sketch up my new plans. It was late that year that I finally went professional to the envy of the people I had worked with in the bank and with some concern on my own part as to my survival. I eased into the work change by using the six months long service leave to which I was entitled. The die was cast. Leaving security in those days was very different from the present time, but it was hard to express the sense of liberty I experienced as I found I had all day to work in the open air. It was also surprising to realize how little extra time there seemed to be in the day.

There were practically no made roads in the Eltham valley and in most places they were rough, yellow clay tracks that were greasy in Winter and dusty in Summer. The yellow box, stringy bark and candle bark trees met overhead in many places. It was delightfully rural then, although there has been an enormous replanting and regeneration of the tree population during the years I have known it. The roadside growth was always heavy in that period, but paddocks were often cleared. I believe it can be shown that the majority of artistic activities have sprung from Melbourne rather than Sydney and the major reason is the combined landscape and climate. Sydney's superlative blue sea and sky, golden sandstone cliffs and red sunlight are marvellous, but they have less nuance and subtlety than the Melbourne bushscape, especially that centred in the Eltham district. Sydney maybe described as a hedonist landscape - where one can take one's pleasure where one finds it and that seems to be always immediately in front of one. But Melbourne has no such equable climate, no such beautiful surf-calling seas. It is subject to rapid changes from heat to cold, sunlight to rain, which keeps the community mu ~h more mentally alert. They never expect things to be the same two days running.

It is interesting that McCubbin the pioneer impressionist painter, did not turn towards the spectacular Dandenongs as he fraternised with the Heidelberg Impressionist Group. There must have been many discussions about the bush and its magic, especially as they excursioned further upstream from Heidelberg. A small contingent including Penleigh Boyd continued on to Warrandyte and settled there on the Eltham side of the river. Most of them, however, led by Walter Withers, went up into the Diamond Creek valley. Today the movement has continued as far as St. Andrews, which is getting close to the stream's source at the top of the Great Divide.

They saw something in the Yarra Valley that the Dandenongs could never give them. That was a dry resilient bush. It was less prolific than the broad-leafed stringy bark which dominated Mt Dandenong - it was crisper, sparser and more survival conscious. It was truly Australian and they were the men of the 1880 and 1890 period whom the historian Manning-Clark considers to be the great Australians. Men of capacity and improvising ability, men who believed in Australia Felix. It should not be forgotten that the Impressionist Painters mainly stayed in Australia and worked for Federation until it was declared, then went overseas-some of them never to return.

The City of Melbourne has always been a land developer's delight. It was especially so in the early post-war years. I can recollect watching houses appear over the horizon in Bulleen and commence scarring the hills overlooking the Yarra Valley at Eaglemont where we lived before we came to Eltham. One Saturday a huge marquee was erected on the highest part of the Bulleen hill and a major land sale took place. It was the bourgeoisie invasion of the Heidelberg valley, made famous by the Impressionist Painters of the 1890's. The scenes that Streeton, Conder, Roberts, Withers and others painted in their 9 x 5 Exhibition disappeared as we watched. While he was staying at our house John Yule painted a whole series of opaque water colours that starkly expressed this new age we called the 'Encroaching City' series.

Back in 1873 my father had gone to live in East Ivanhoe when he was four years of age. There were then only three houses in that area; their own, which was the farm that is occupied today as the East Ivanhoe Golf Course. The De Castella house, which they knew as MacArthur's and Whipples, which stands behind the East Ivanhoe Shopping Centre. There was also a tiny pair of brick buildings with slate roofs that had until about 1946 been situated on the nearby Heidelberg side of the valley. They had been occupied by the Impressionist Painters themselves. They rented them for 2/6d. per week. The only trouble was that they got behind in the rent! Nor was this all! Burley Griffin, the famous American Architect, took up residence in Glenard Drive in about 1926 at the other end of this beautiful place.

I myself built opposite his tiny house in 1939. Prior to the second World War the river valley at Heidelberg was a place of great light and atmosphere. There was hardly a house to be seen. In the mornings it would often be bathed in sunshine except where the mists still lay to mark the meandering course of the Yarra flowing across the low country leading back to the Baw Baws and through the gap between the Healesville and the Warburton ranges. These great mountains had unerringly beckoned men of adventure from the very founding of Melbourne.

The appropriately named Mt. Pleasant Road was part of the first road that led out of the city to take people into the wilds of the mountains. In 1875 two coaches a day left Kangaroo Ground for Woods Point, and Cobb & Co. took at least five days to make the journey. Charles Wingrove, who was a Surveyor General for Roads for Victoria lived on the Main Eltham Road close to its junction with Mt. Pleasant Road. Several of the original road reservations in the Eltham area were not useable because of the steep hills and gullies they traversed.

In some parts early tracks ran through private land. In front of our own property he permitted the half formed carriageway to continue across a five acre allotment. He then by arrangement clipped off an acre in the form of a triangle from Anderson's Orchard and added it onto the land they owned on the opposite side of the road. In this way some of the original road reserves became landlocked and the adjoining owners purchased them from the Council and divided them between themselves. Mt. Pleasant Road led up to Bells, who were the earliest settlers in Kangaroo Ground. They were situated adjacent to where Eltham College now stands.

The extraordinary twists and turns that remain on Mt. Pleasant Road must be the despair of Civil Engineers, but its rough unbitumened serpentine course is a delight to anyone with a romantic bone in their body. Is it any wonder that, as I gazed out from our back porch in Heidelberg, I vowed that I would eventually live in Eltham, especially as at that time I was required to turn my back on it each day when I headed off to work in a bank in the city or in the suburbs.

There is a mystery about the distant Australian landscape that sets it apart from all others. It has to do with the clarity of the light, which on most days enables one to see extraordinary details and distances. First there was the great red gum savannah landscape at Lower Plenty that merged further out into the little bouncing hills of which most of Eltham is composed. Eltham is really the first natural bushscape out of Melbourne and it is also the best. It certainly affected the original Impressionist Landscape Painters in that way. They made their journey from Box Hill, moving through Heidelberg and Lower Plenty until they reached the Diamond Creek.

History is in many ways geography in action. Most social developments and artistic movements have been stimulated by forces of circumstance.

No one knows, for instance, who invented the principles of Gothic architecture. The movement became necessary to express the new ideas that were current at the time. Young men were seeing visions that could no longer be expressed by the dreams old men were dreaming. The historical reality of the early Industrial Revolution which used timber for power instead of coal, became a major factor in the replanting of trees and the restoration of the entire landscape of England by 'Capability' Brown and others. It was also a strong catalyst to the Lake Poets in their discovery of the wonders of wild nature.

The development of the mud brick movement which began in Eltham in 1947 has had similiar implications. Had there been no war, there would have been no shortages, and if there had been no shortages there would have been no mud brick building. And if Eltham had not contained a small community of dynamic people the movement would never have germinated. Today, the earth building movement in Australia is developing into national proportions and it is really just beginning in other areas.

Eltham's 30 years of earth building has produced a whole new way of looking at how we may live, particularly as we watch the promise of the postwar world dissolving before our eyes into depression and despair. It offers a new and interesting life, the return to living in the landscape and being independent of the multi-national syndrome and its consequences. It can likewise remove the modern professional who separates design from structure and lays a dead hand on creative building. In all his 50 London church designs, as well as the 33 years he spent on St. Paul's, Christopher Wren was never widely separated from the scene of action. Sweat, tears and blood were the mortar that bound his living stones together, other than the committees and liquid luncheons which are among the main weapons of modern architecture.

Our local community must cherish its unique place in Australia. In general it has developed a consistent approach to living, which should be defended at all costs against those who are unaware of our traditions and who may try to change them. In a previous chapter it was made clear how the most powerful ingredient in our inspirational make-up is the special bushland and the low hilly terrain in which we live, coupled with the unparalleled colour and light which are our daily portion. The fact that the number of trees in central Eltham has more than doubled since 1945 is an indication of how universal and powerful the movement has been. Eltham was fighting the S.E.C. and other government authorities in the 40's and 50's over the retention of indigenous trees. In the Christmas season of 1956 our conflict with them came to a dramatic confrontation that made headline news in all the daily papers for a week. It started in the Herald, was repeated in the Sun and taken up by the Age two days later. After four days, it was appearing in the New York Times.

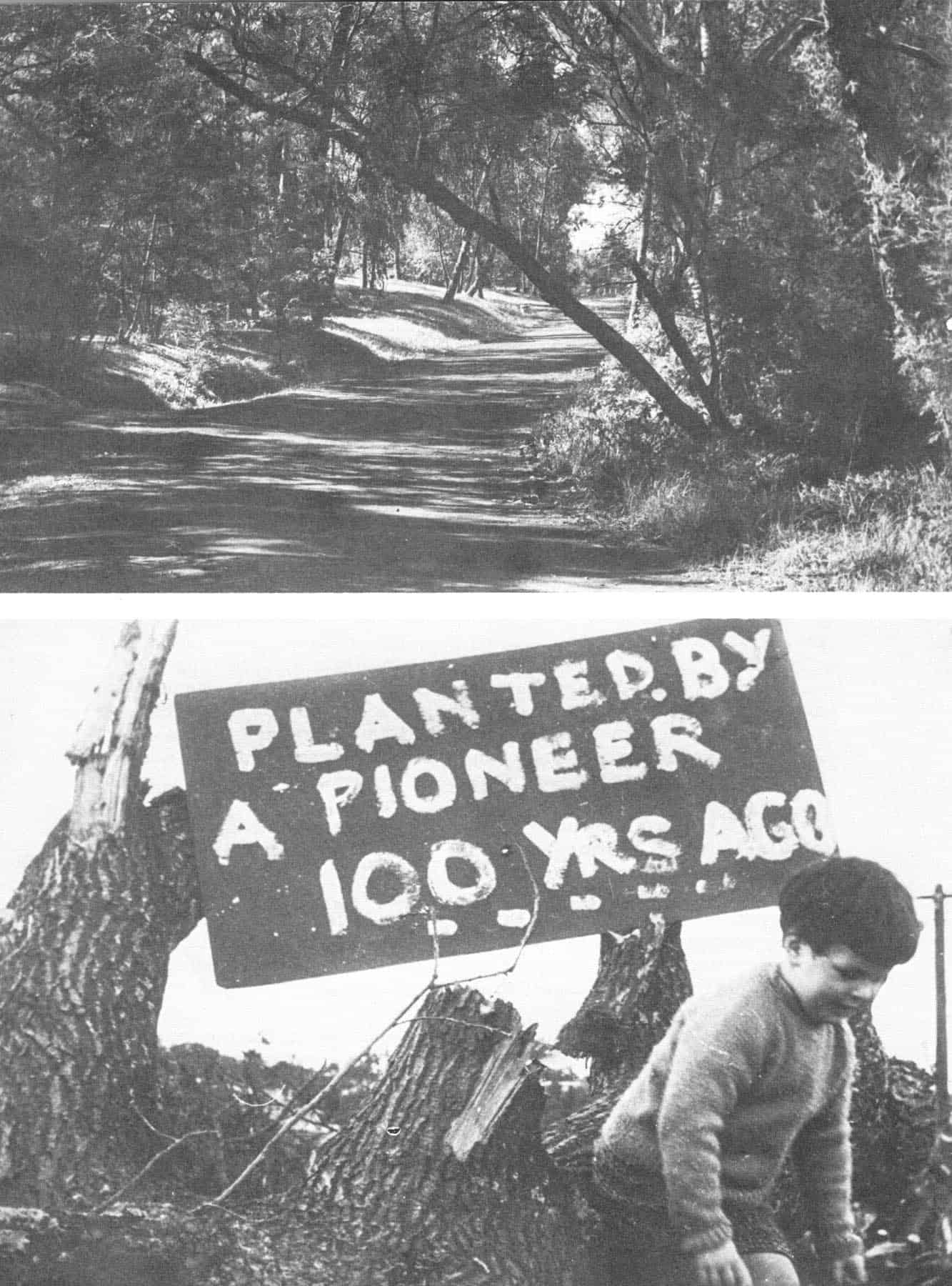

Above top: Old Mt Pleasant Road.

Above bottom: My son, Hamish (aged 2½ years) attending his first protest against the depredations of the Sate Electricity Commission 1956

Above top: Old Mt Pleasant Road.

Above bottom: My son, Hamish (aged 2½ years) attending his first protest against the depredations of the Sate Electricity Commission 1956

Some S.E.C. workers cut down two 100-year-old oak trees in Franklin Street. The inner Eltham community launched a frontal attack on bureaucratic bungling and arrogance that they have never forgotten.

When the chairman of the Commission delivered his New Year's speech some weeks later, he emphasised that the commission's first responsibility was to protect trees. This was the antithesis of their previous attitude. For many years to come, tree-lopping Commission workers always pretended they were not there when our small explosive group passed by. With Council assistance, we also carried out free native tree plantings on the nature strips of most roads in the Central Riding in the 1950's, when the rhododendron and the gladioli flanked by pampas grass and flowering fruit trees were still being introduced into the most 'desirable' eastern suburbs.

The building of the Busst House, which followed the completion of the Periwinkle, was, I believe, the most mature mud brick house designed at that period. It related with true understanding to its steep site and expressed the flexibility of earth building with sincerity and authority. It was a positive alternative to architectural thinking that was based on the T -square, the pitched roof and the stud wall. It exploited the flexible nature of earth to develop a new sense of flowing form and shape. The owner, Miss Phyl Busst, had been a student of the Montsalvat Artist's Colony. She and her brother, John, had lived there for some time. John went off to Dunk Island on the North Queensland coast and stayed there for the remainder of his life.

When Phyl Busst decided to return to Eltham, she asked me to design her building for her. It consisted of two large main rooms, a living room and a kitchen area downstairs and a studio and bedroom upstairs. The entry to the house was made at an intermediate level; the bathroom and laundry were placed one above the other in a curved section of the house related to the entry. As it was a steep site, it was decided to bifurcate or split the house along the middle. This made it possible to walk out of the studio bedroom onto the bitumen and creek gravel roofing that covered the timbered ceilings and heavy beams of the living area.

It always struck me as quaint that Phyl, who was at that time reputed to be much more economically secure than most people in Eltham, would have elected to purchase land on that rich-sounding corner of Diamond and Silver Street. Her holding consisted of five standard-sized bush blocks that retain the character of the original landscape of that corner of Eltham to this day. The two-level site was quite complicated because most earth moving was then in its infancy. It was the first time we were able to hire a crawler tractor to do the work and even this highly technological instrument finally had to stand back and await blasting operations in certain parts.

The drilling for explosives was done by hand, Les Punch came into his own on such occasions. He would start drilling into stone to a depth of three or four feet by simply bouncing a type of crowbar called a jumper bar, which he twisted a half-turn every time he hit into the stone. From time to time he would stop and insert a thin rod onto which a small spoon was attached at one end into the hole to ladle out the powdered stone his drilling had produced. It was a slow and painful process which could produce a callous on each hand for every foot of depth that was won. Finally, the dynamite charges would be laid and fired with varying results. Not infrequently, Les had to spit on his hands, laugh philosophically, and start again.

The explosions would echo around the quiet hillside and in a few minutes time odd-looking characters would emerge from the bush. They would look knowingly at the results, pass a few words about the next shot with Les as they sniffed up the lingering fumes of the blast, and dreamt about the day when they worked on the gold mines further up towards the mountains. Horrie Judd was now firmly established as foreman, and he and Gordon Ford, who prided himself on his sun-tanned body and fine physique, would toil side by side to get the site ready for pouring the new-fangled concrete slab.

Others gathered for making bricks. On the first occasion we discussed brickmaking, it was quite late on a cool evening. Neil Douglas, who was one of the volunteers, surveyed the stony-looking soil for a while and then announced he was going up the hill to where he knew there were some mushrooms growing. Neil was the true nature man of the group and the others watched him set off with athletic strides with a quiet, admiring attitude. They felt instinctively, rather than expressed, that if things really got bad he would be able to help them survive in the natural landscape. Neil disappeared over the hill and was forgotten as they discussed the contract price of the bricks to be made. It eventuated that he never returned. He indeed had a very good idea of survival. It had become clear to him that making mud bricks in that place could prove to be beyond the realms of sanity. His survival capacity consisted of knowing when to leave.

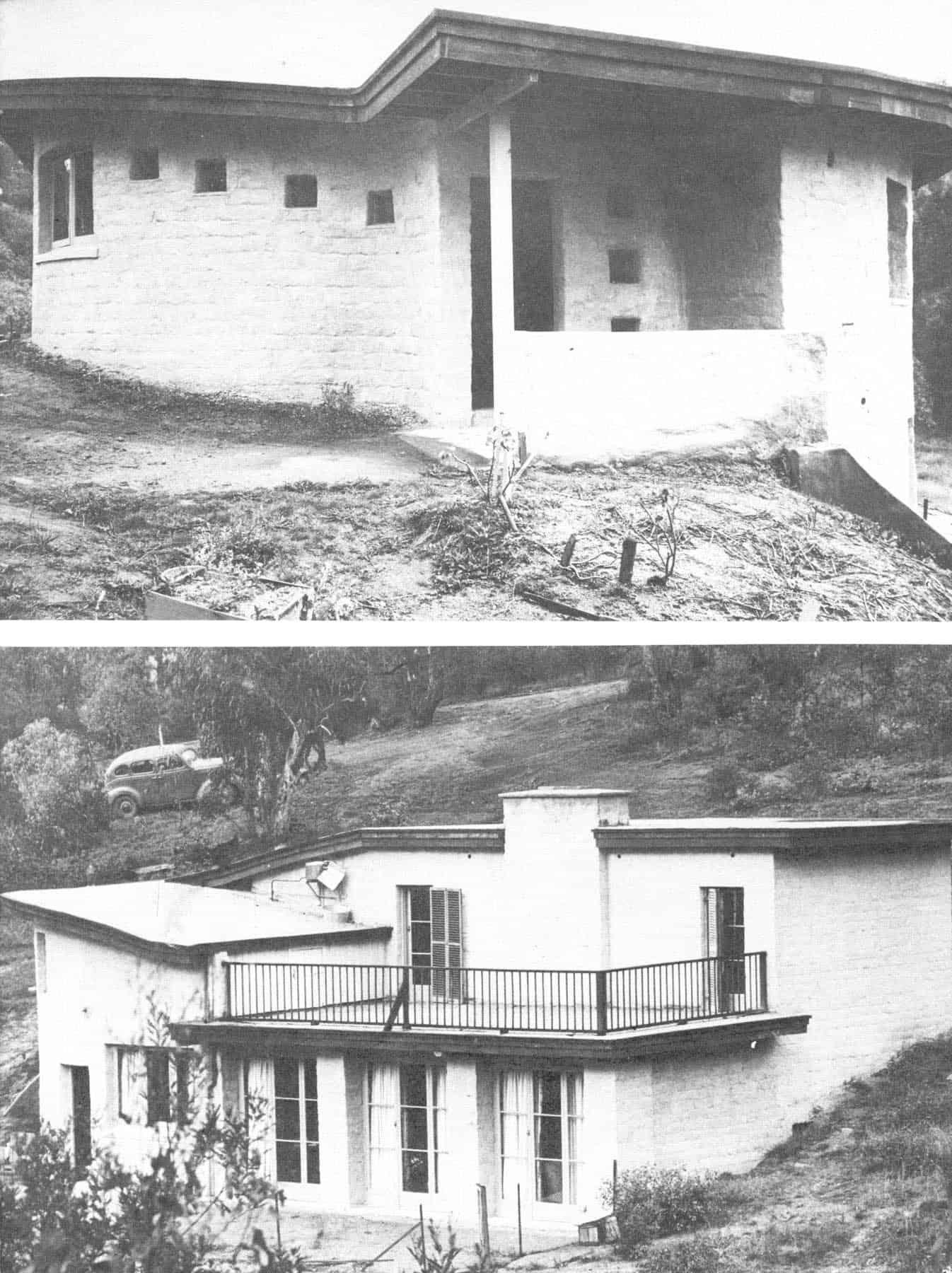

Above top: The entry to the Busst house demonstrating the flexibility of earth building.

Above bottom: The Busst house immediately on completion 1949

Above top: The entry to the Busst house demonstrating the flexibility of earth building.

Above bottom: The Busst house immediately on completion 1949

Earth building had always contained a strong physical labour content, particularly prior to 1950 before mechanical equipment of all kinds become a daily practice. The pinnacle was reached at the Busst House the day Horrie Judd and Gordon Ford poured the concrete slab. They mixed 52 bags of cement, with the appropriate screenings and coarse sand, into concrete, placed it in position and screened it to a reasonable finish in the one day. They scorned using a mechanical concrete mixer and concrete trucks were not yet available. The method was effective, but when it is remembered that this weight of material to be mixed and placed would be more than 20 tons, i.t gives some gauge of their physical strength and endurance. They first placed the materials in a dry state at the top of the slope and stood opposite each other with the heap between them. They drove their shovels into it and turned it over twice in a dry condition. As it rolled down the hill, the process was repeated after it had been wet down. By the time it reached the edge it was ready for placing. Underlying this vast physical effort were the inflexible wills of two strong men who would have died rather than admitted to each other that they could not have continued.

The Busst house brought out the full flowering of Horrie's physical powers and skills. The strong, flowing shape and monolithic curved walls of the house were magnificently done. He fully grasped the design possibilities. At a time when standard building materials were at their lowest ebb, he contrived to use what was available with character and direction. The problem of fascias, which curved sideways and downwards at the one time, was solved by lapping the double widths of six-inch by one-inch hardwood together in short lengths and butting them to each other, then trimming the curving lines with his tomahawk.

The curving sweeps of the upper ceilings were achieved by combining rafters that ran from side to side of the building and laying two-inch thick 'Solomit' on top of it. This flexible material was again weatherproofed with bitumen and creek gravel. Further rigidity was given to this packed straw ceiling decking by stapling eight-gauge fencing wire at right angles to the rafters. The building has been standing for 30 years and is as sound today as it was when it was erected.

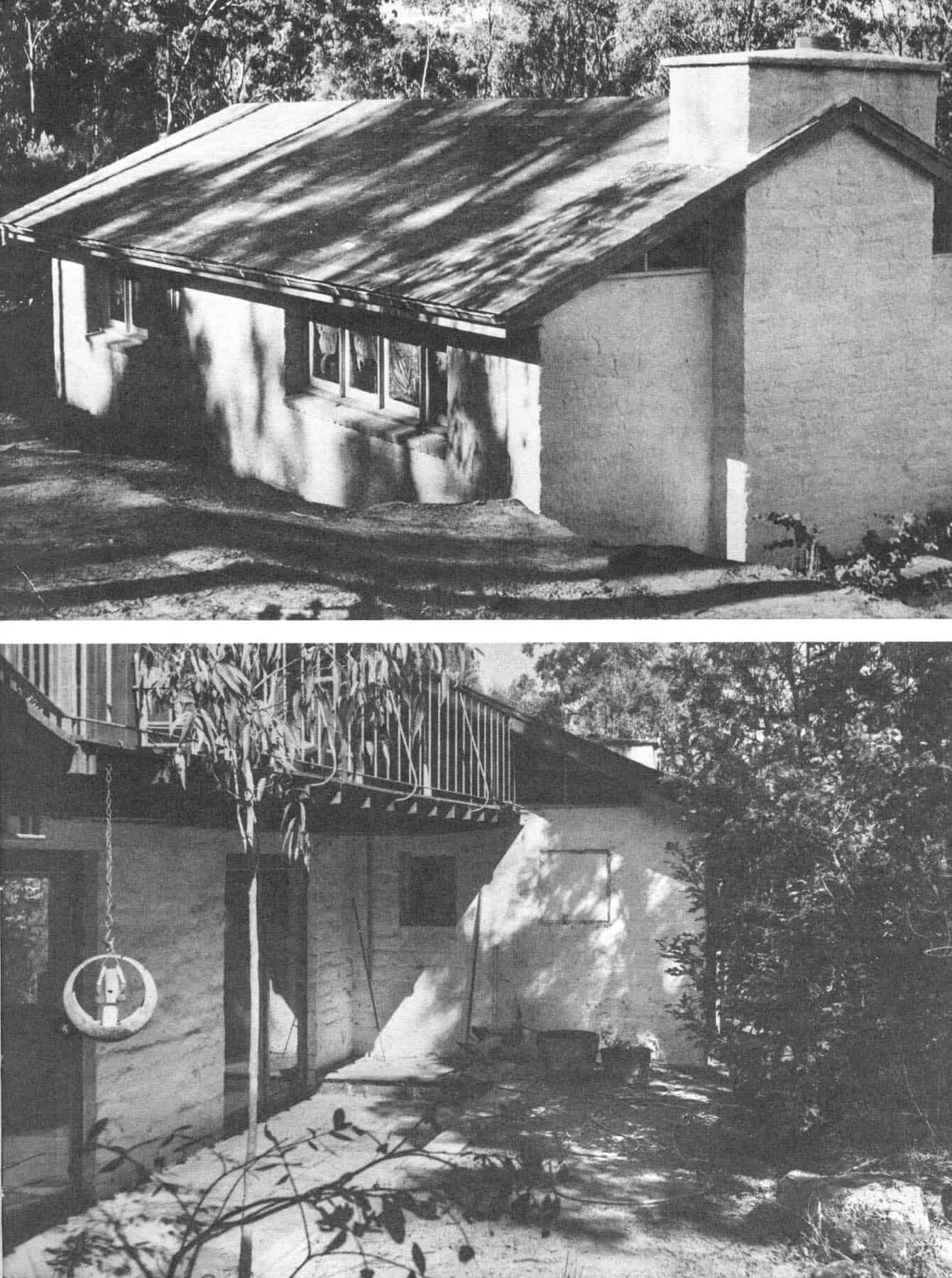

Above top: Downing/Le Galliene house, Stage 1, 1949.

Above bottom: Downing/Le Galliene house, Stage 3 1958

Above top: Downing/Le Galliene house, Stage 1, 1949.

Above bottom: Downing/Le Galliene house, Stage 3 1958

The Downing- Le Gallienne House, stage 1, was commenced shortly after the Busst House was roofed, but still remained unfinished inside. The new house excavation was deep rather than extensive in size, and, because we were not able to get a suitable excavator to it, it was dug by hand. Horrie undertook this work and to some extent was helped by Les Punch and one or two others. The material itself was the most beautiful that could be conceived of for making mud bricks. It was a type of pliable clay, which, when wet, worked like stiff caramel. The excavation angle was about 45 degrees; it had been cut in steps of about one foot by one foot. These bore silent witness year after year to the remarkable stability of the natural ground in that part of Eltham. The building was erected in four stages between 1949 and 1964 and when the last stage was underway, the original steps, which were only earth, were still almost as square as when they were originally dug.

Horrie had acquired a full-time helper called 'Mac' MacDonald. He continued with the Busst House on the west side of the valley while Horrie was working at Downing's, which is in Yarra Braes Road, near Reynolds Road, some 212 miles away. One day, Mac drove over in his Morris Minor to get Horrie back to Busst's for some reason. Horrie left post haste on his trusty bicycle. Yarra Braes Road was very precipitous and more like a river bed than a roadway in 1949. It can still get bad in 1978, but nothing compared to what it then was. Horrie preceded Mac down the steep incline; near the bottom of it he was making about 30 miles an hour when his front wheel caught in a rut. 'Mac' described how he watched Horrie become airborne in one direction with his cycle flying off in the other. It was enough to kill an ordinary man, but all it did to Horrie was to break his thumb. He himself was as undaunted as ever, but was unable to work for some months. This was a serious blow to the ongoing program, but it all held together through others joining in.

Wynn Roberts, who had been a foreman on the second house we built in Heidelberg, was one of these. He was fast developing into a brilliant actor and we were soon to lose his services, but he never lost his love for timber. In his home on the western slopes of the Dandenongs he works part-time making beautiful hand-wrought furniture.

Phyl Busst was determined to have a full-sized bath in her house. It was an item of building which was next to impossible to get without waiting some 12 months for delivery, so we decided to form one out of solid concrete. Jack Fabro, the stonemason, was asked to produce this complicated article of toiletry. The skill he displayed in his construction still reflects his Italian craftsman heredity. Jack Fabro was taught and worked with his uncle, Caesar Moretti. Both his grandfathers had been genuine Italian stonemasons who built bell towers, arched bridges and other marvellous structures that only Europe knows. Jack and Caesar built beautiful stone chimneys in various parts of the district for those who could afford them. He has over the years been sought after for special work at the Melbourne University and the restoration of churches in the city.

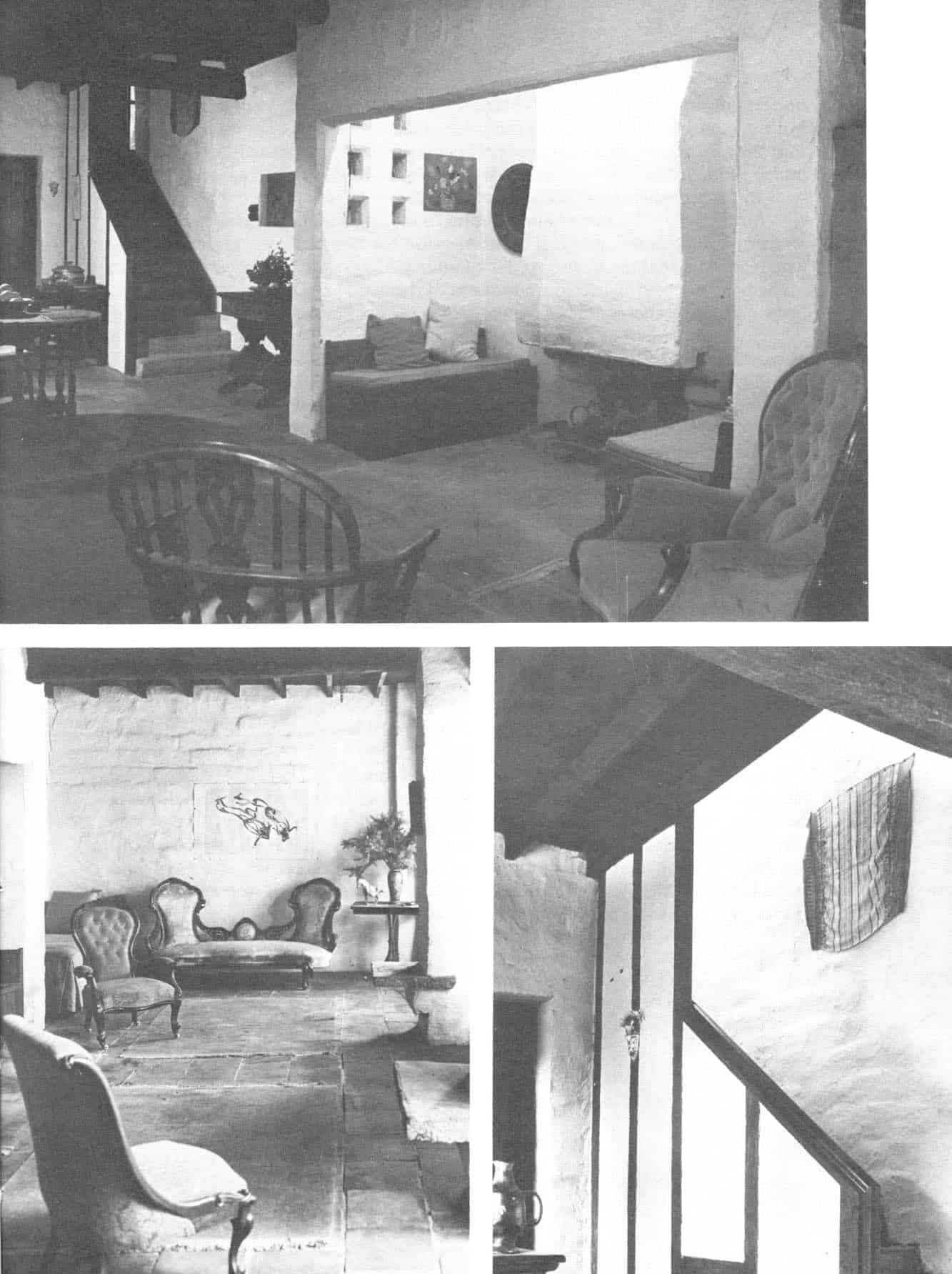

The Busst house, the main living room

The Busst house, the main living room

In the early post-war years, when Eltham was emerging from being a tiny village into its young and exciting community lifestyle, there seemed to be one of everything in it, each of which was known by.name. Because of the great shortage of cars, there were only two working trucks available for carting material in those times of scarcity. This meant that there were only two carriers to do the work and they each enjoyed a particular place in the minds of those who were building. One was Garnie Burgess, who was also a marine dealer. He had a second-hand yard in the Main Road, next to Staff's traditional old-fashioned grocery. Ernie Owen was the other. He was the local carrier per se because he went to the city each day. These gentlemen still reside in the village, although Garnie's hair has turned silver and Ernie's truck has long since been swallowed up at the wrecker's yard. Jack Fabro recalled to mind one of the amusing anecdotes concerning Ernie Owen and his famous truck, which everyone both loved and hated. Hated because it was often late, and loved because we were always waiting for something that it would bring. One day, as he was passing through the famous stone piers at the entry to John Harcourt's residence, called Clay Nuneham his overloaded vehicle pushed one of them onto its side. John Harcourt was called and arrangements were immediately taken in hand for its reconstruction. Jack Fabro came over and had a look at it and went off and brought back a couple of big jacks. As he had originally built the pillar, he knew what it was made of and that it would never break up. The only re-building it would need would be to be stood up once more.

The whole operation was completed during the afternoon. John Harcourt came along a little later and committed one of the classical non- understanding remarks of the district. 'It didn't take you long to get all that built up again', he said in some surprise and admiration, oblivious to the fact that the mortar had been dry, for years and the lettering was still intact on the posts. Not a muscle of Jack Fabro's face moved as he meditated on the blind spot in the middle of John Harcourt's vision.

Sonia Skipper still continued on with us, specialising in wall treatments and finishing work. I was full of admiration for her facility and philosophy. She learned her skills at the Artist's Colony under Justus Jorgensen, which made her a once-in-a-lifetime exponent of the mud brick vernacular. She was responsible for the character of the Busst House, including the tiles on the floor, which she made herself from a magnetite-based concrete with powdered wood fillers and other ingredients.

The Busst House is truly a building where every practical and experimental technique was tried or used. Phyl herself was an excellent client, cheerful in adversity-that meant when the money was running outand understanding of our efforts and appreciative of our capabilities. I remember having to accompany her to her solicitor one day to strike an agreement about the final cost of the building. He turned out to be a rather blunt man who appeared puzzled that a person of some means could waste their money building in mud in the Eltham bush. When a point was made, he would look at his client and utter in sepulchral tones: 'Is that all right with you Miss Bust?', instead of calling her Miss Busst using the long 'U' sound, as if to warn her that her final financial collapse was imminent.

The complete amount of the building was agreed to and it soon reached completion; I even made a little bit of money out of it. To do even this required that the building finish on a precise date. I hurried to the site on the Friday afternoon we were to hand over, a few minutes before the usual finishing time, expecting to find two or three still working on the final details. But they had all gone home.

As I looked around it seemed silent and lonely. No one was laughing or hammering. The debris was all swept up and its living quality had died. It was like an empty shell. As I walked down the Diamond Street hill towards the station I contemplated what it had all meant to me: I was staggered to find it meant nothing at all, I didn't feel anything. It mattered not whether I had done it or not, despite the fact that I was conscious that it was an excellent building in its own right.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >