We Are What We Stand On, The Evocative Panorama

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

The Evocative Panorama

Author: Alistair Knox

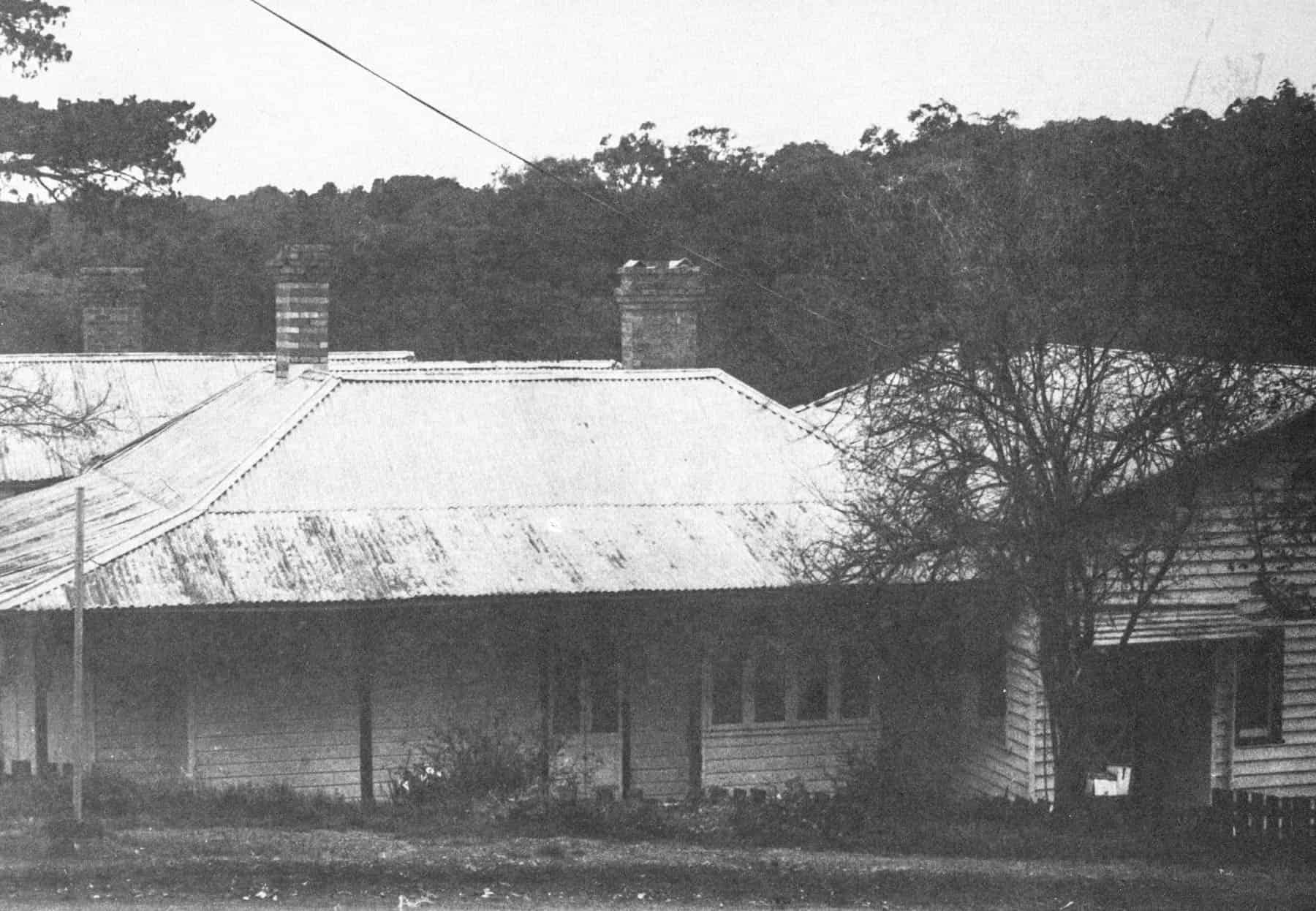

Walter Withers' house and studio. Cnr. Bolton and Brougham Sts

Walter Withers' house and studio. Cnr. Bolton and Brougham Sts

It came as a delightful surprise to me to find that the mud brick buildings I first initiated and put on to a commercial footing so long ago, should have expanded into one of the most exciting social movements Australia has known. Earth wall construction is, of course, the oldest and most used method of building there is. Some two-thirds of all structures in the world have employed one form or other of sun-dried earth walls. It is found in every country, except in odd and special circumstances where there is an absence of clay and earth, or in extreme arctic conditions that make it impossible.

I was recalling the erstwhile years one autumn afternoon in 1978 as I stood on the highest corner of the Bolton Street/Brougham Street intersection on the west side of the central Eltham valley. The panorama evoked nostalgic recollections of the district and its surroundings. From where I stood, I could see clear over the roof of the house that once belonged to Walter Withers, the well-known early Australian impressionist painter who had died there in 1914. It was sited opposite on the low side of Bolton Street. Its white weatherboard walls have been considerably altered over the years, but the low, shading-verandahs that face Bolton Street are exactly the same as they were depicted by other artists of the Impressionist School who so frequently wandered up and down the valley along its quiet rural roads, inspired by its beauty.

They had found it necessary to excavate the sloping ground more than a foot deep along the verandah line to provide head room. This caused the house floor to finish lower than the adjacent road level. The old house has a traditional painter's look about it. It is as if Withers had painted it there rather than built it from the way it clings to the hillside sloping down to the floor of the Diamond Creek valley. The five chimneys that penetrate the roof are all of the same design, but it is clear that some were erected at different periods to the others because of the patterned brickwork used in the earliest part of the building.

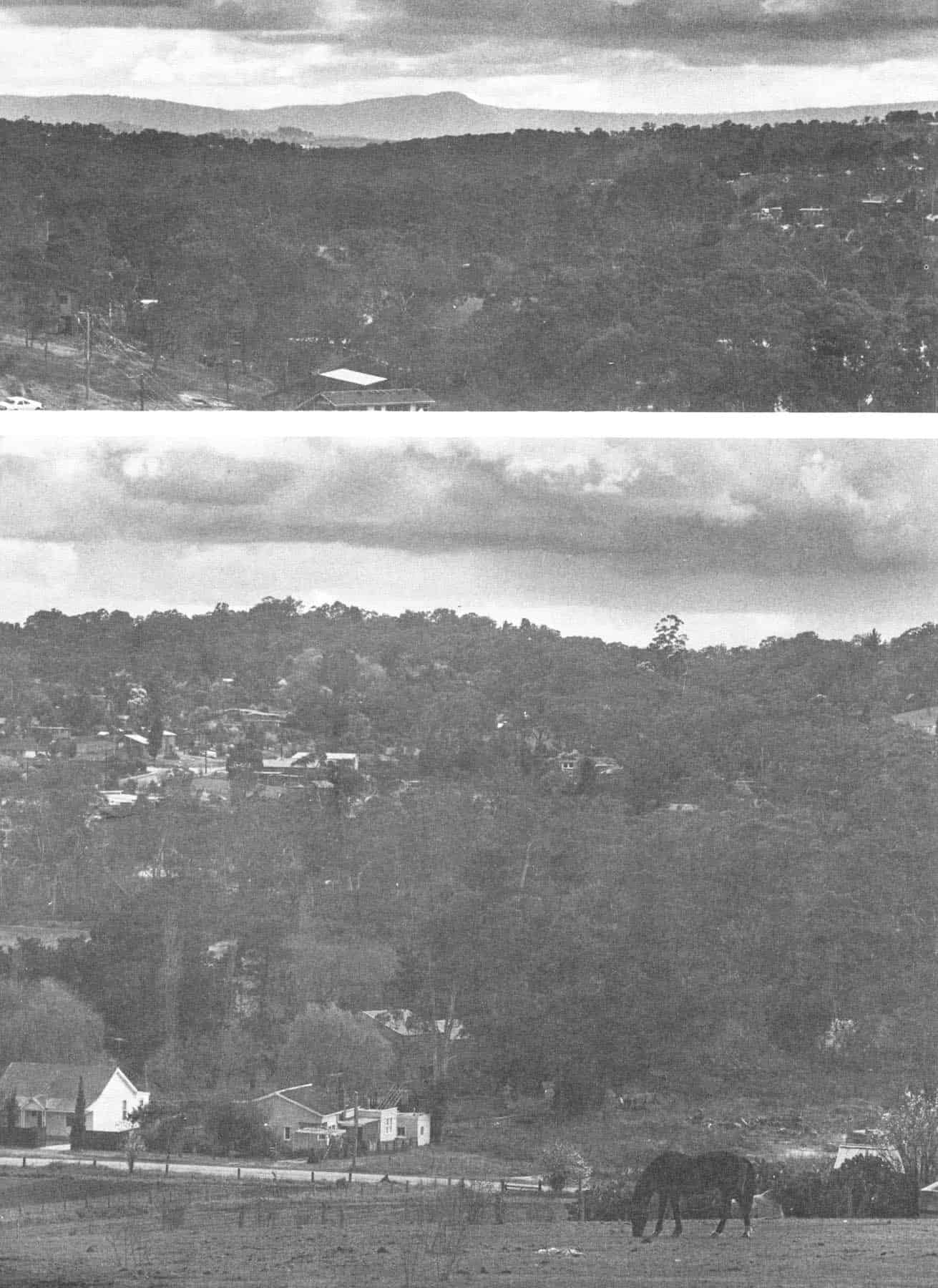

Eltham Valley today: Above top: Looking north to Mt Sugarloaf.

Above bottom: The Eltham Region looking east across the Valley Amphitheatre.

Eltham Valley today: Above top: Looking north to Mt Sugarloaf.

Above bottom: The Eltham Region looking east across the Valley Amphitheatre.

On the south side the walls of his studio rose higher than the rest. They provided good even light admirably suited to his continual striving to express in his paintings the character of his district with its subtle variations of light and colour. Much of what he painted can still be clearly discerned today, although some parts of the valley are considerably changed. A light industrial zone now terminates on the opposite side of the road at the Withers' corner and an accumulation of inappropriate industrial roof lines is creeping up the hill. In other areas, however, the scene is in sharp and happy contrast to this ugly assault on the eyes and the mind. It is very much the way I knew it more than 30 years ago.

I remembered as I studied the Withers' buildings how a friend once told me of the solicitous lady who was reputed to have cleaned out his studio the day after he died and burnt up all the 'rubbish' on that sad occasion. He then continued to explain in solemn tones how he himself had later searched high and low in the ceilings and under floors for a lost canvas or two, as if he felt the lady had done him out of some irreplaceable treasure. This sense of the indefinable and possible still appears to brood over the district.

The whole valley can be seen at once up to the Eltham railway station on the north, down to a point close to where the Diamond Creek flows in to the Yarra River on the south. The valley floor is a flood plain running north and south at an average width of about a quarter of a mile. Beyond that point steep slopes surround it on all sides to create the sense of an elongated amphitheatre. Houses cling to its sides like immovable spectators silently observing their rural community changing from its delayed adolescence into maturity.

Much of the development is half obscured by many years of concentrated tree growing, but the towers of Montsalvat, the artists' colony, can be seen surmounting the sloping cemetery land on the south-east, and the Eltham High School complex and a new Leisure Centre dominate a similar southerly position on the valley floor on the west side of the creek. Discerning householders scanning the valley patterns can observe that its emerging character was different from anywhere else in Victoria and probably Australia.

The valley floor which flooded once or twice each winter had prevented much of it from being built on. An original English countryside pattern that had been laid over it in the form of cherry plum rows and hawthorn hedges still survives. In springtime their pure white lines of blossom run down to the creek to mingle with the meandering river wattle for a short melodious period that is more European than Australian.

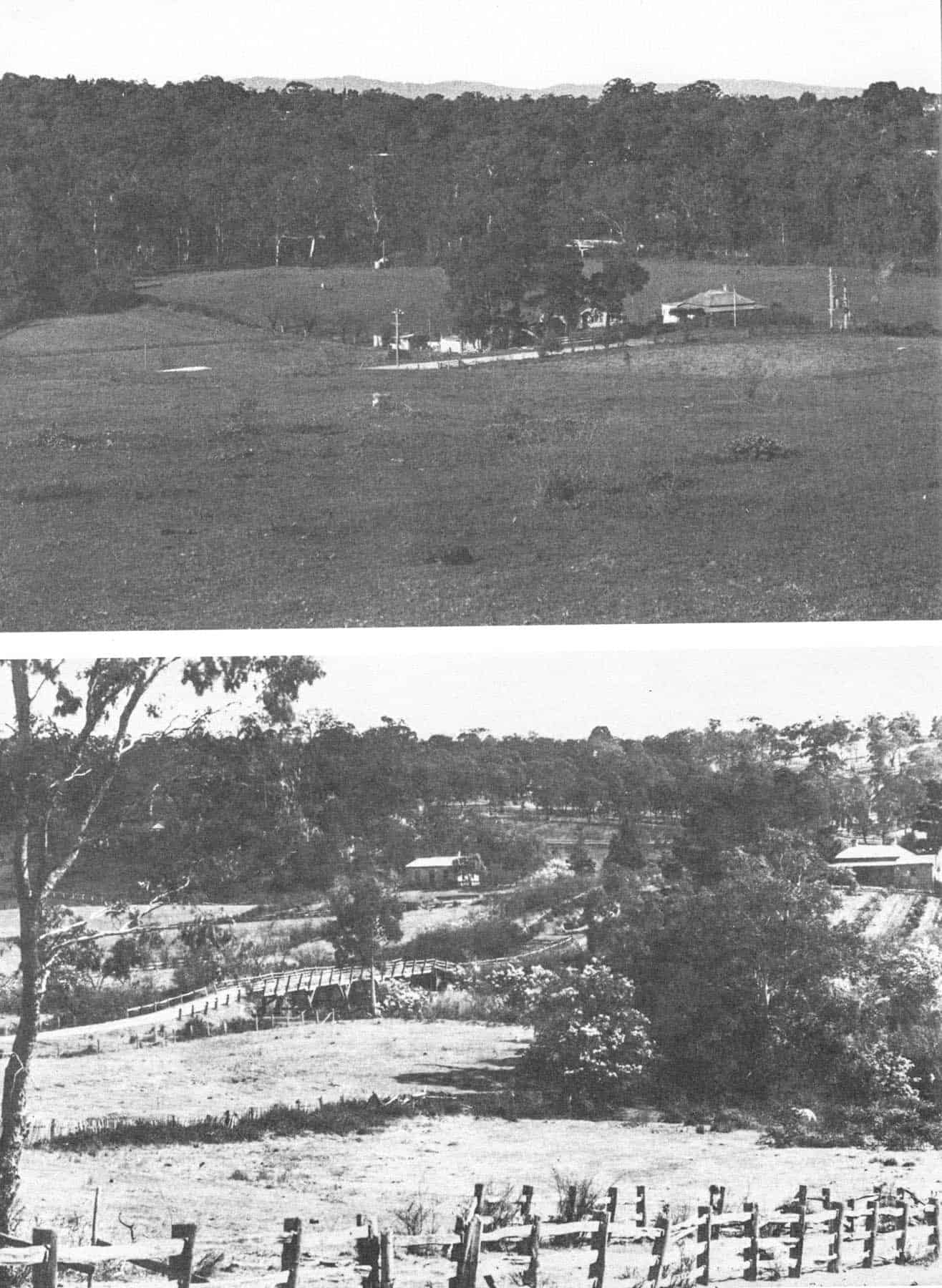

Above top: Eltham Valley looking south-east towards concrete bridge.

Above bottom: Eltham Valley 19, overlooking the Town Park site

Above top: Eltham Valley looking south-east towards concrete bridge.

Above bottom: Eltham Valley 19, overlooking the Town Park site

A small industrial zone once existed there in the nineteenth century. It consisted of a flour mill, a brewery and a tannery. The mill persisted into the early twentieth century and one of the mill manager's houses still remains. It was renovated four years ago and developed into the Eltham Living and Learning Centre which encourages the present inhabitants of Eltham to recapture the natural occupations that were once used within it. Bee-keeping, gardening, weaving, carpentry and a host of hand and heart activities are enacted in and out of its environs, in clear contrast to the housebound sherry drinking loneliness that can occur in the newer housing areas. There the roads are immaculately lighted, curbed and paved and the buildings are new, large and expensive, but the soul life of the valley is notably absent.

The waters of the creek once flowed more abundantly than they do now that part of them is syphoned off for reservoirs and irrigation. Its purity was once the basis of the brewing that was sent down to the army barracks in St Kilda Road. Now the quality of it has changed with the coming of the twentieth century and the petro-chemical industries which have polluted practically every living stream on the face of the earth. In the prevailing climate it is a remarkable fact that the platypus still survives a few miles farther up its course.

It was the unusual geographic structure of the valley rather than the intentions of men which originally gave it its special character. What nature provided, however, tended in the course of time to draw a small discerning, population into it in the way Withers migrated from Heidelberg after the railway came at the turn of the century. They grew to love its intimacy and separate valley identity, its nuances and variations of climate and its bushland surroundings. In autumn, winter and spring it can at times, become a fog valley. From the high sides, fluctuating and half-visible scenes can be glimpsed constantly changing and merging. In the mornings and at sunset the house-fire smoke rises vertically in the still air until it reaches the level of the highest slopes. It then spreads out in many long horizontal strands, somewhat reminiscent of ancient Chinese mountain paintings. The Eltham township site was originally to be located mostly on the hill west of Susan Street and south of Brougham Street, and the reason that so many roads between Hillcrest Avenue on the east and Bolton Street on the west still remain unsealed is because they are public streets and a charge on the shire. Eltham, like most semi-rural districts is perennially short of money, which means that the roads will probably remain as they are for an indefinite period. It will allow the inhabitants to enjoy a human alternative to the perpetual bitumen surfaces that have caused much of Melbourne's vast suburban wilderness to degenerate into a social desert.

The site originally selected by the early land surveyors was a noble swelling hillside that looks directly north to Mount Sugarloaf, which dominates the Kinglake Range skyline. The main ridge runs east and west, but the Sugarloaf Spur swings southward and is some miles closer to Eltham. It is impossible to believe that the source of the Diamond Creek, which can be traced from the nearby valley, could rise anywhere else than on those slopes. The whole valley drives like a wedge of ever-decreasing width right up into it. It is a whole unbroken region that has generated a united introspective community, too large to be merely hillbilly and still small enough to be itself alone.

The original site which had difficulties in those early days was changed by one of Melbourne's first land subdividers. Josiah Morris Holloway purchased a tract of land on the north boundary of the Government Township area and subdivided it into blocks of 40ft. frontages in 1851. Access roads were 33ft. and 66ft. wide. He was one of the very first of a long line of land developers who have been manipulating the Melbourne landscape ever since. The area was known as Little Eltham North. He took his plan of subdivision down to the Port of Melbourne. In 1854, the gold rush had made Hobson's Bay the busiest anchorage in the world. There were over three hundred ships continually moored in its waters with another waiting to get in as soon as one moved out.

Although it was only about 5 miles from Melbourne Town, it could cost more to get self and chattels there from the ship than it did for a berth from Liverpool to Hobson's Bay, a distance of 12,000 miles. It was an ideal time for Holloway to offer building sites to the new immigrants for £5 a block, especially as gold was beginning to flow from alluvial diggings and reef mines in Research, Kangaroo Ground, Panton Hill and St Andrews.

A village soon started to appear north of the present Eltham Hotel and the adjacent Fountain of Friendship Hotel that then stood on the opposite side of the road. Holloway's enterprise that moved the town northward was finally confirmed when the rail station was placed within it. There were a variety of reasons that caused the Eltham community to differ from any other in Greater Melbourne with a tenacity that persists to this day. This is a most interesting phenomenon because the pattern of nineteenth century cities has generally shown them to be mobile and to conform with every social and economic change. They have insufficient historical background to have an individuality of their own.

The basic reason for Eltham's character is unquestionably its hilly terrain, its colour and light landscape, its atmospheric subtlety and its early gold mining that has emotionally drawn the landscape painter, the writers, the poets, the musicians and now the school teachers into it in great numbers. But like the Jews of old, 'Not all who are born of Abraham are Abraham's children'. Most understand it and, regrettably, a few do not. Since before the turn of the century, there has been a group within its wider population who have come because they were enthralled by the natural beauty and the calls of the teeming birdlife that echo through the valleys. These created in their hearts an indefinable sense of magic.

Where Josiah Morris Holloway saw its open spaces as a means of profit-making, this other group desperately strove to keep it open in the way the Creator had left it. Until about the middle of the 1960s they were remarkably successful. After that time, the rich and affluent eastern suburbanites started casting sheep:s eyes at this unkempt bushscape, which was so different from their well-ordered English lawn, blue spruce, silver birch and Japanese maple gardens.

These were beginning to pall as the rediscovery of the Australian native flora developed from a revolution into high fashion. Eltham was once again under threat from the land profiteer, who would butcher the living qualities of its inhabitants to make his Roman holiday. It will always be the same in modern democratic societies-the shopkeeper versus the artist. It is hard to decide which is worse; the shopkeeper turned artist, or the artist turned shopkeeper-and it is always likely to happen. Eltham's future depends on continuing assaults from the manipulators and the blind do-gooders being repelled by those who understand and believe in her. The best recipe for her survival is a social crisis every two years and a freeway threat every five. It keeps people alive and continually re-evaluating what they have. 'The price of liberty is always eternal vigilance.'

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >