We Are What We Stand On, Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Author: Alistair Knox

The mud brick building movement really got into its stride in Eltham in 1948. The Frank English house and the Macmahon Ball studio developed a run of earth wall buildings. I designed several during the next three years. Each one was interesting and highly personal because it was at that time impossible to raise a loan on a mud brick building. They tended to be the expressions of an individual rather than an alternative lifestyle.

It is very different today. There is growing evidence that mud brick properties are among the most acceptable securities on which to lend. This arises from the increasing demand by more and more people to own them and to live in them. Now they are in danger of becoming the prerogative of the rich. A significant problem that confronts earth buildings in today's social climate is the fact that they are now fashionable and a status symbol rather than the background for creative living.

In Eltham it would be reasonable to estimate that there are forty mud brick houses under construction at the present time. There can be no doubt that this has been a major factor in maintaining the special way of life that is so much in evidence in the district. As a person whose work interest is in environmental planning, I believe that Eltham is the unique community of Australia. There are gloomy pronostications that it is a declining society, but this is not borne out by the facts. Every earth building stimulates more earth building and also develops a new group of people, both to build and inhabit them. It is an inspiring experience to walk on to a job now being designed or built by the sons and grandsons of the first earth builders. They are expressing new design ideas and capacities all the time.

The Periwinkle house, the Busst house and the first wing of the Downing/Le Gallienne house were all started in the year 1948. In addition, a large homestead was commenced in Murphy's Creek, four miles north of Tarnagulla, an old gold mining centre in the middle of Victoria. Meanwhile, there were several individuals constructing their own houses in the Shire of Eltham. The interest in earth building was almost at fever heat because of the number of post-war marriages, coupled with the possibilities of more adventurous lifestyles on the one hand and the lack of standard building materials and services on the other.

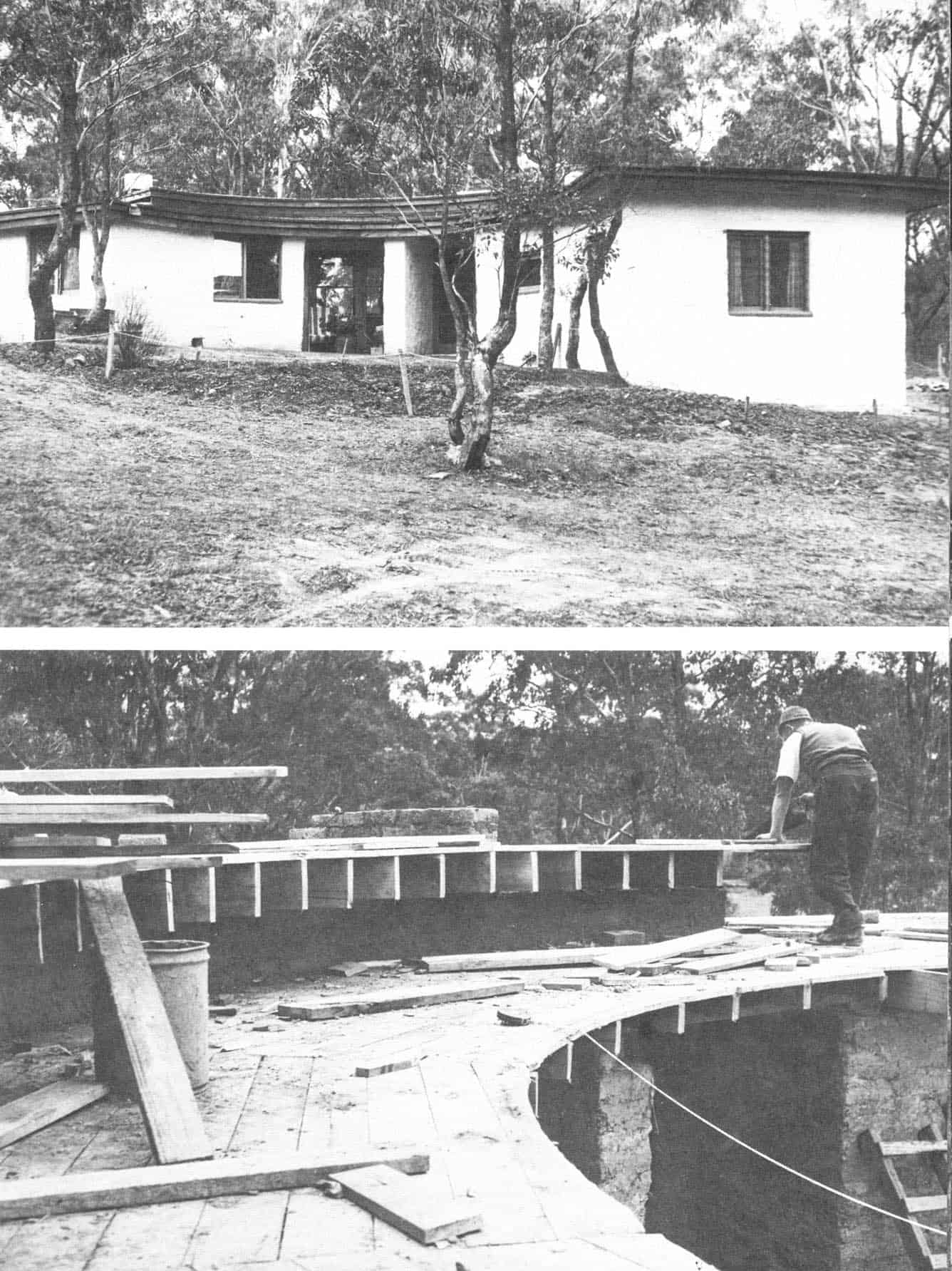

Above top: The Periwinkle house 1948.

Above bottom: Horrie Judd at work 1948

Above top: The Periwinkle house 1948.

Above bottom: Horrie Judd at work 1948

I was sometimes asked several times in a single week one standard question which ran something like, 'How much would it cost me to build a mud brick studio about 30' x 20' if I did all the work myself?'. To provide some sort of answer, I called the enquirers together. One sunny Saturday afternoon, we set off to look at a large subdivision that was on the west side of the Eltham valley and extended right up the Lower Plenty hill. It was called Panorama Heights Estate. More than fifty potential owner-builders went to examine this land which could be purchased for as little as £40 per block with a deposit of £10 down and five shillings a week repayment. There was a concern by some at the high cost of the land!

Everyone however seemed to be impressed with the possibilities of living in this lovely hillside in 'a related community style. In a moment of over-enthusiasm, I suggested that to purchase a couple of extra blocks for community services including a creche and a laundry would be a good idea. The word 'creche' had a devastating effect on the gathering. You could see the ranks thinning while you watched, but some people did stay and build, including Tim and Betty Burstall. Their mud brick building started off very modestly but grew year by year into quite a sizeable structure. Freddie and Verna Jacka began immediately below them and the Clendinnen's also built nearby a little later, after they purchased the land from Ray Marginson, the original investor. Hal and Joy Peck took up a site above them which overlooks the dam where we all swam during the hot weather, especially if mud bricks were being erected in the vicinity.

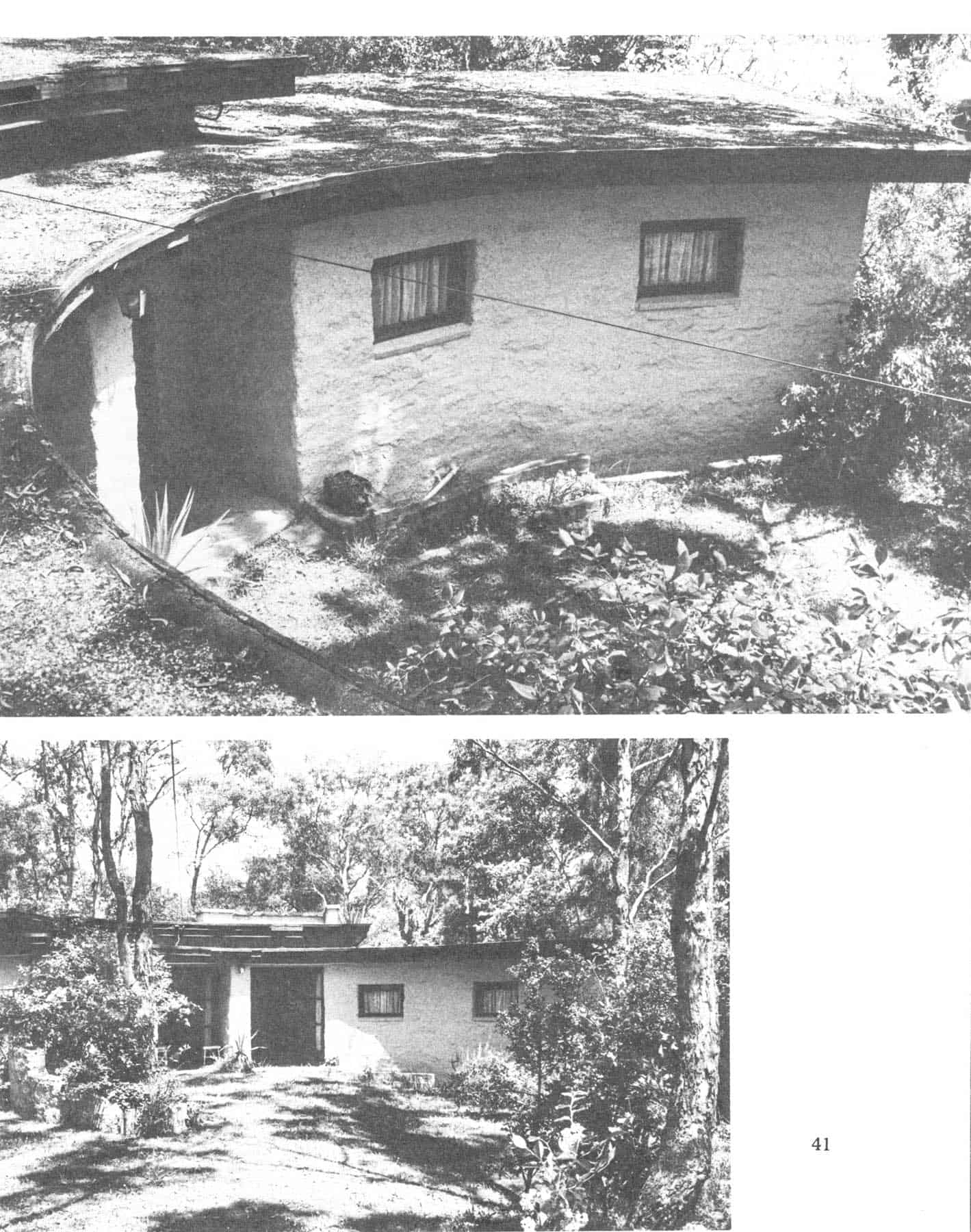

Sonia Skipper was again in charge of the Periwirikle project. It was a single bedroom house designed and built for a Mr. and Mrs. Jack Holmes. Its plan was an expanding circle' or spiral, which started from a seat built around a tree in the garden. The plan looked exactly like a periwinkle shell lying on its side. It was on two levels with a bitumen and creek gravel roof. It attracted a lot of interest and comment at the time in architectural journals and was mentioned by Robin Boyd in his book 'Australia's House'.

Tony Jackson, Ted Howard and Neil Douglas and a new worker called Horrie Judd, who was to become a tradition in a variety of ways, all laboured on it. The Periwinkle was situated in Batman Road to the north of the township which still had only half-a-dozen shops in it in 1948. Most building had occurred to the south, adjacent to the area of Josiah Morris Holloway's 1851 subdivision. The Holmes site was among spindly box trees and clay soil that was so ubiquitous to Eltham. It was secondary growth. There are many examples of the original trees along the Main Road to Research which are of great age and dimension.

The biggest yellow box in the district was on the corner of Batman Road and Park Road. I designed and built a house there some years later for the Corbetts in a position very close to the tree. One day, in the middle of a storm a great piece of the tree fell and landed on their roof. It punched a substantial hole in it. Fortunately, the house had a large exposed beamed ceiling. In any other circumstances, the tree would have crashed right into the lavatory which was occupied at the time by the German mother of Mrs. Corbett. So far as I know, it was the only case we experienced of falling trees-a single instance in between 500 to 1,000 houses we have either designed or designed and built.

The repairing of the roof had to wait for a fine day so that a large sheet of Stramit Board could be placed and the whole lot covered with malthoid and bitumen in a minimum time. Just as the roof was opened up, a squall of wind and rain appeared from nowhere and the whole house was once more inundated. The lady of the house, Krista Corbett took it all in good part. Krista was a beautiful blonde German girl with many talents. She and her husband separated some time later and Krista became something of an international figure. She was in Iran at the time of a severe earthquake and we never heard of her for many years. We used to wonder if she could have lost her life in that catastrophe and had been found with her beautiful white face lying amidst the dust of wrecked adobe houses. We eventually discovered that she was very much alive. She had remarried and was very rich and living across four continents.

The Periwinkle house from the roof 1978.

The Periwinkle house from the roof 1978.

The Periwinkle house from the courtyard 1978

The Periwinkle was my first example of using curved walls. I set it out with Sonia one Saturday and boxed up for a slab construction. The slab was a very new practice. In fact, I thought I had invented the slab floor building. It was not until I studied Frank Lloyd Wright a little more carefully that I found that it was what he had useg in his 'U sonion' house more than ten years earlier. My methods were more economical than his because he used 6" slabs with peripheral footings. Ours were only 3" thick and used a very light reinforcing. After we had completed a few such foundations, the CSIRO turned up one day to examine what had happened. When they saw the simplicity of the method compared with their own attempts, they said, 'We may as well tear up what we have done and start again'. There is no argument about the fact that Eltham produced the slab floor system which is now so much a part of modern building techniques in Australia.

Earth structures are direct and simple and it is this fact that has caused me to think through the slab floor process and make it work. It was once believed that concrete on the ground would inevitably be damp, but as I designed the excavation shape it was always made lowest where the surrounding natural ground was highest, so that water ran away from the building in every direction. It was before water-proofing membranes were available and we had to develop our own design traditions. These have remained unchanged except that there is now too much steel used and slabs have become unnecessarily thick and expensive. Building Surveyors and members of the Australian Standards Association have probably never heard of Frank Lloyd Wright's remark about over-specifying. He said, 'The factor of safety is the factor of ignorance'.

The dimensions of the bricks in the Frank English house and the Macmahon Ball studio were 12" x 9" x 6" and were used as stretcher bond, exposing the 12" x 6" faces on both sides. Justus Jorgensen had used 12" walls in the Artist's Colony and laid them as headers with the 9" x 6" ends exposed. Both methods had worked without a hitch. When I planned the Periwinkle, I decided to make the walls 12" wide because it was at that time recommended by the Commonwealth Experimental Building Station and also because we were using curved walls. We used bricks of 18" x 12" x 4" dimensions and had curved moulds made to produce them for the curved walls. In practice, it proved both hard and unnecessary.

It was subsequently decided that a 10" wall was just that much better than a 9" one and not as wasteful as one 12" wide. Each new step required a new evaluation of the overall concept. It demanded methods which deleted the inessentials. It was also accepted that the walls which were more than one story high should be thickened to 12" or 15" for the first 10' of their height and then reduced to 10" thereafter. This finally produced a brick of 15" x 10" x 5" laying the 15" x 5" faces exposed, which has now become the current practice. In all these instances, the bricks were weight bearing and not the infill walls that are so much a part of the present scene. For walls which are non-weight bearing, a 10" thickness is completely satisfactory for up to two storeys. The problem of the large curved bricks of 4" thickness was the difficulty of stacking, because the best practice is to lay bricks on their long, flat edges when they are dry.

Work proceeded satisfactorily on the Periwinkle and there were bricks dry and drying all over the slab and the surrounding clearing until one night it rained incessantly and bitterly. When we saw the sight the next day it was disastrous, especially as we had stacked the dry curved bricks on their edges. Because they were only 4" thick and resting only on the corners rather than on the long, flat faces they broke in hundreds. Tony Jackson and Gordon Ford set to work like fanatics to clean up the site. In the afternoon, Sonia came with a horse and cart to carry away the worst of the stacked breakages and to restore a sense of order. This was the first of several traumatic instances I was to experience dealing with earth walls. They conrront any person who adopts an alternative lifestyle. Their purpose is to discover some iron in the soul that is so essential when one adopts innovative practices in most callings, but especially in building.

Environmental building is either the best form of work for the fullblooded man or the worst. You can give away the day if the temperature rises above 38°C, but you can't leave it just because it is a bit showery. A cold wind interspersed with rain squalls can make it a lonely occupation. To bruise your thumbnail on such a day by dealing it a generous blow with the hammer makes you wonder why you ever started. But when the next day dawns clear and sunny and the bush is alive with the call of the magpies, it is the most satisfying occupation that can be imagined.

In the immediate post-war years, there were practically no private cars and men walked to and from work or rode horses or bicycles. I rarely worked on the site myself. I always felt guilty hurrying to see the job after I left work at the bank at 3.30 p.m. and caught the train which landed me at the building about 4.30 p.m., just a few minutes before they were due to finish for the day.

As the Periwinkle was approaching its half-way stage, it become clear to Sonia that the men who were working for her had not sufficient experience to complete it and she herself was not a carpenter. She arranged for me to meet Horrie Judd, who lived on the very rim of the highest part of the natural Eltham amphitheatre. We set out one night after a dinner at Montsalvat to visi t him. We had to scale the steep slopes on the other side of the creek valley. Night was falling and the grass got longer the further we went. It rose up to our shoulders and there were no such things as street lights in that landscape. When we finally groped our way to Horrie's house in Reichelt Crescent, I felt that I had been on a tiger hunt.

Horrie agreed to start working for us within a fortnight. He explained that he was not a tradesman carpenter, but a foreman labourer. These statements were more or less the facts. He was both rough and strong and the most conscientious worker I have ever known. Single-handed he began a new era in mud brick building. He approached work in an entirely different spirit from the type of employee who was recovering from war neurosis or avoiding returning to an indoor occupation. He was punctilious concerning working times, arriving at the site about two minutes before eight in the morning and leaving at exactly the specified finishing time in the afternoon. His morning break was exactly ten minutes and his lunchtimes could be measured to the second.

He never broke these rules. Men working with him would stand up immediately he got up and grunted, which was his way of saying lunch time was over. His difficulty was that, although he would battle on against all odds himself, he seemed doubtful about leaving much responsibility to others. In some ways he was justified. In either case, he was a doer-not an encourager. Another outstanding fact about him was his ability to combine his great strength with the work in front of him. He had a single-minded discipline. When he would start digging a hole, he simply seemed to disappear into it. The quick, short strokes of the pick would be followed by the rhythmic rising and falling of the shovel and he would maintain the same speed right up until knock-off-time. He was regarded with awe and respect by the ordinary worker of the period as a phenomenon-a man apart from others. Many stories and myths surround his works of prowess.

In some ways he descended into the Eltham valley amphitheatre from his hilltop house like the local champion going into battle with the hard clay-loam soil and the twisted eucalypts, armed with a sharp pick, a squaremouthed shovel, a hammer and a blunt saw and chiseL His billy swung from the handle bars of his bicycle as he propelled himself over the unmade roads, with his strong legs working like pistons. I recollect Tim Burstall arguing with another University graduate on a building site as to whether Horrie could move more soil by hand in a given time than a Ferguson tractor driven by Keith Joslyn. Keith was a local who was himself becoming a great tradition in the earth moving age by mechanical means, not only for the Shire of Eltham but for the whole of Melbourne.

Horrie worked for me for some two years and was the main builder on the Periwinkle, the Busst house and the first Downing/Le Gallienne house. He dug and poured footings, made and laid mud bricks, pitched the roof and did the carpentry. During this period he had Les Punch, a Victorian Railways employee in at odd times to help him. Les made bricks and took charge of blasting operations and other ancillary jobs. He lived in an ancient timber house in Silver Street, where he was developing a Museum which in his own words would be 'a must in every Tourist's Guide Book.' Model trains ran in and out of rooms and under beds and there was a galaxy of oddities in all corners. It was a dream that never eventuated.

When Horrie started working on the Periwinkle it was ready for erecting the curving and expanding roof on three levels. The only timber available was rough and tough hardwood. The strength of his forearm enabled him to force his badly-set saw through the wood. It would have stopped another carpenter at the second cut. At times he seemed to use a chopping action, rather than sawing. Despite the disastrous water-logged beginning, the house was eventually roofed with bitumen and creek gravelas most of our buildings, because of their shape, were at that time.

As it approached completion, rapidly rising costs had forced up the original estimate from £800 to over £1,000. The same outcry occurred as with the English house. I received a Solicitor's letter threatening drastic consequences if I decided to press my claims for the terms of the cost plus contract. Again, I was forced to retreat, leaving an almost completed building some £200 out of pocket. I was finding it hard to admit that earth building was not as cheap as I thought it should be and harder still to be tough on clients.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >