We Are What We Stand On, The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

Author: Alistair Knox

My introduction to the two most able and fascinating men who ever came to Eltham took place in 1948. They were Professor Richard Downing and his long time friend Dorian Le Gallienne.

They asked me to design a weekend house for them in Yarrabraes Road, off Sweeneys Lane. That area was known as Rutter's subdivision, because it has originally belonged to a doctor of that name who had been burnt out by the 1939 bush fires.

The fire started a a point near the junction of Lavender Park Road and Kent Hughes Road and raced up the river to Warrandyte to burn out most of the existing settlement. It was certainly the blackest day in living memory in Central Eltham, although there have been several subsequent serious fires in the district.

I was to discover that Dick and Dor, as they were often referred to by their friends, were the most intellectual, urbane and witty company any district contained.

As we walked around their land on the river side of Yarrabraes Road, I was being continually enlightened by their erudition and inspiration concerning natural phenomena. I saw the environment in a new context. Two or three years in the district had prepared me for this enlightenment but they were the ones to supply it.

Professor Dick Downing was about to set off to work for the International Labour Office in Geneva for four years. He left Australia as their weekend house was nearing completion and did not return until 1954. Dorian also went away. New natural environmental concepts were crystallizing in various places at this time. Their penetrating comprehension hastened the process. They saw what was required with unerring judgement and appreciated its totality, mystery and wonder. There was no such thing as a 'planned' Australian landscape. There were no lawns, herbaceous borders, non-indigenous growth or suburban formality. Their tree planting consisted of the concealment of planting, the creation of instinctive masses and voids merging back into wilderness. Natural informal growth came right up to their doors and so did the indigenous birdlife.

There were four main stages of their building complex: the first was a single space 36' x 18' with a pitched slate roof that appeared to support itself by magic. This was achieved by pouring concrete lintels along both sides of the top of the walls and forming timber structures within and around them which cantilevered the rafters so that the opposing members of each pair met at the apex and were bolted to one another.

The kitchen was divided from two bunks along the centre line of the building with a wall that only rose to seven feet. A shower and cupboard were constructed at the far end of the house which had walls of the same height. By this means it was possible to look from one end of the building to the other through the gable clerestory windows within each gable.

The wooden walls were made of rough-sawn 6" xl" hardwood, the only easily obtainable material at the time. They were nailed in pairs to each other with staggered joints and held top and bottom by 'U' shaped capping of timber. It was early days for getting away from stud walls and it proved a much better answer. The fireplace was made entirely of mud bricks and is still working with complete satisfaction 30 years later.

This was about the fourth house in which we had used a concrete slab and it was at this time that the CSIRO visited me at Downing/Le Gallienne building to see how we were getting on with them. When they found I used no waterproofing membrane at all, but merely watched the drainage to the site, they decided to tear up their complicated laminated membrane waterproofing and start again.

The great individuality of the Eltham environmental systems have been their simplicity. It has merely been a matter of putting one thing on top of another and never using two things where one will do. We were objective and reduced every movement to its simplest possibility.

This was necessary because there was virtually no one but ourselves who would or could build them. They had to be understood and constructed by amateurs. Professionals mostly thought they would melt in the rain and also thought it was a loss of face to be seen working on one.

I have observed a long series of architectural styles and mannerisms come and go since the second world war. The only ones that have made more than a minor ripple on the water have been David Yencken's and his Merchant Builders constructions. They succeeded because he kept them simple, as we did. He came into the field a lot later than us and often repeated our systems.

The first panel wall construction we undertook was in Mont Albert in 1952. For the next fifteen years it became our standard method, except for a proportion of sculptural buildings in earth, solid timber, stone, glass and hand made brick. We only used plaster half a dozen times in the 500 buildings we designed and erected and the additional 500 we designed and supervised for clients.

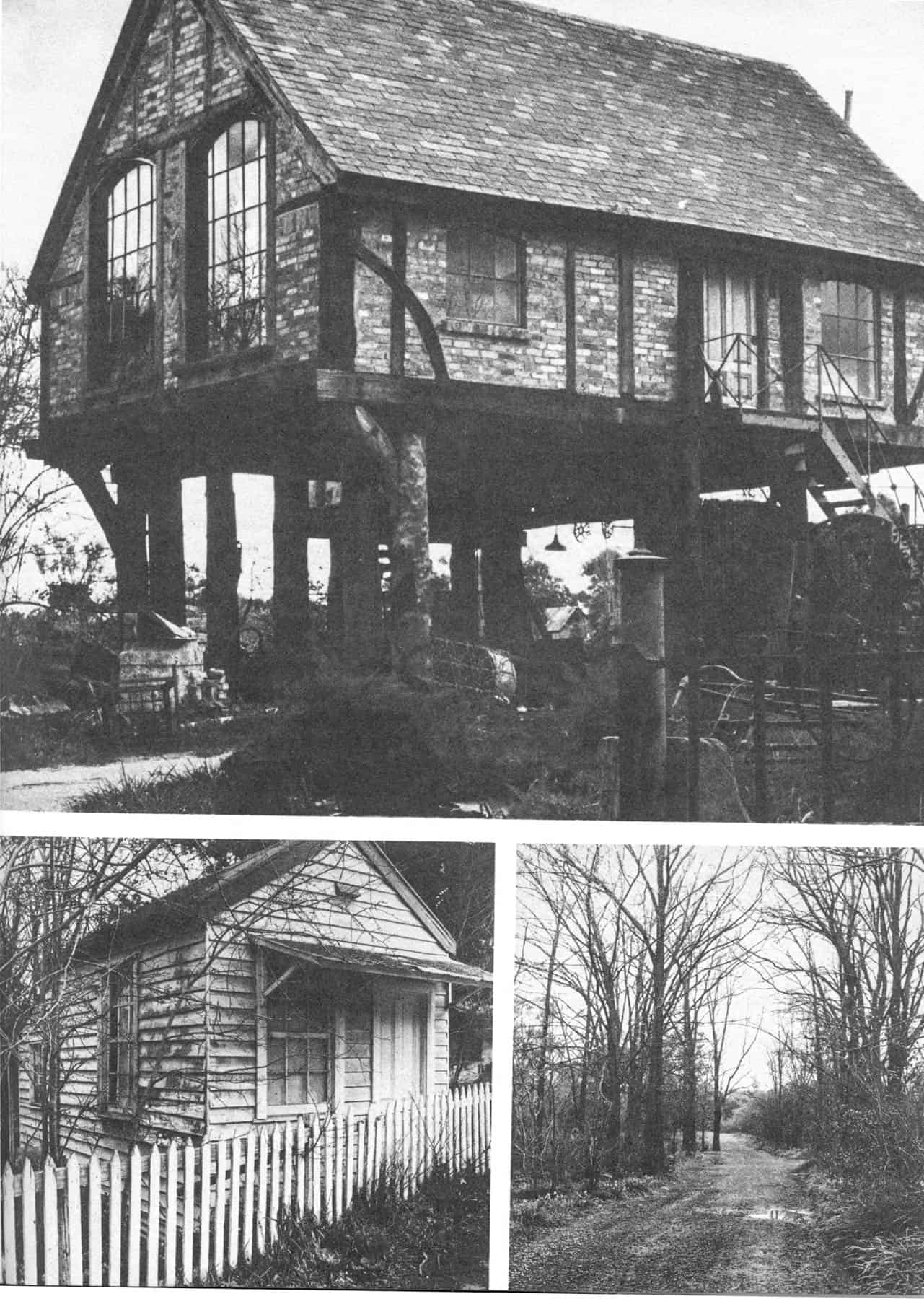

Above top: Matcham Skipper's studio.

Bottom left: The 'Ticket Box' where Margot tried to sell $10,000 paintings for £50 in 1952.

Bottom right: The Dalton St corner beside the Ticket Box showing an Eltham cherry plum hedgerow in winter time.

Above top: Matcham Skipper's studio.

Bottom left: The 'Ticket Box' where Margot tried to sell $10,000 paintings for £50 in 1952.

Bottom right: The Dalton St corner beside the Ticket Box showing an Eltham cherry plum hedgerow in winter time.

The most glamorous use the 'ticket box' building in the corner of the Jarrold House was put to, was when it was used for selling art objects by my second wife, Margot, in about 1950. I had originally married in 1937 and in 1948 moved from Eaglemont to Eltham. My first wife and I built and lived in one of the first houses to be erected in Mossman Drive, Eaglemont. We had three children who all became part of the Eltham scene when they grew up. We separated after the end of the war and came to live in Eltham. It was not long after this that I met up with Margot, my present wife. When she came to Eltham, she lived in a variety of domiciles and did a great number of different jobs.

She had previously worked in the Arthur Merrick Boyd potteries in Murrumbeena and she occasionally painted with the Boyds, Perceval and Douglas, who were all close friends and associates. It was the time before any other painters had any money because they could not sell their paintings.

Margot decided to open the 'Ticket Box' at weekends to sell on commission Arthur Boyd and John Perceval canvases and incredible pottery pieces decorated with nymphs and butterflies and bushland decorations. Some were of immense size and quality but were almost impossible to sell in those artistically immature times.

Practically no intinerate art fancier was willing to risk purchasing of these great emerging artists, although it was possible to buy an Arthur Boyd painting for as little as £8. They were a great attraction for the High School children, who had never seen such dynamic and frank painting before.

Margot also had a stack of large Boyd and Perceval canvasses which they had taken off their stretchers. She kept them under her bed. We were unable to sell them for £50 each, although within two or three years they were bringing a four figure sum. A couple of years after that they were all fetching a minimum of £5,000 to £10,000 each.

I have seen many of them change hands at auctions or pass into the galleries and private collections. They were the high point of John Perceval's most famous period. One of John Perceval's paintings done just after 1950 was sold around 1972 for $61,000, then the second highest price paid for an Australian painting.

We, like all our contemporaries, did not have any money to buy Perceval's paintings, though we understood their quality. To see them hanging in the galleries of the rich recalls romantic times and places. There was the Gaffney's Creek series, the Williamstown paintings, and the series that John did out at Whittlesea and Cottlesbridge, when he would arrive at our house on his way home, covered in green paint with the fruit of his labours riding on his luggage rack, with dry gum leaves adhering to them.

Meanwhile, Margot lived at Peter Glass' first house when he was in Europe and also at the Fabro cottage behind the Fabro's lovely Italian farmhouse when he returned.

Betty Burstall and Margot were often thinking out interesting ways of making money. Some of them were practical, others a little hilarious. One of the nicest was their idea to have a pie cart to sell pies to the high school kids. They had the particular cart in mind and had actually purchased the material for awnings. This charming idea unfortunately did not get off the ground.

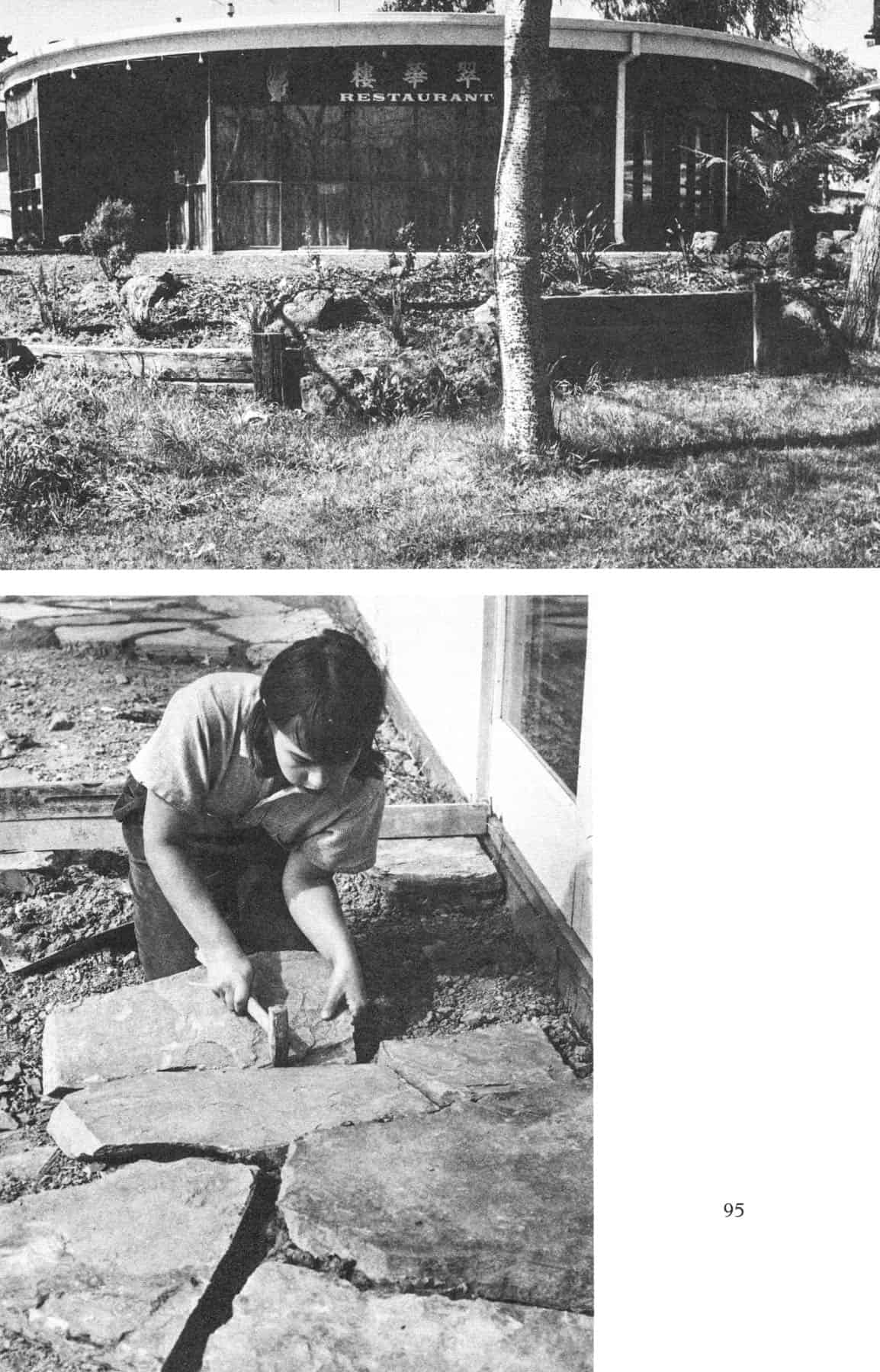

Above top: La Ronde Coffee Lounge, which is now a Chinese restaurant.

Above bottom: Margot Knox paving

Above top: La Ronde Coffee Lounge, which is now a Chinese restaurant.

Above bottom: Margot Knox paving

Another activity however, did. This was the paving of the La Ronde Coffee Lounge on the corner of Main Road and Cecil Street for people named Ribton Turner. It is now a Chinese Cafe. It was not one of Margot's best jobs because she was six months pregnant with her first child and the weather was in the high nineties. It was because of her condition that she asked Betty Burstall to labour for her and mix the cement and carry the slate pIeces.

Betty, like all Eltham girls, believed in a good suntan, even if it meant risking cancer of the skin. She turned up to work in bikinis, which was very way-out in those days of circumspect one-piece bathing costumes. Together they made the most fascinating and eyecatching work team that has ever happened in Eltham, notwithstanding the mistaken ideas some people had about what occurred at Montsalvat.

La Ronde was an extremely low cost building. The window walls were made from 4 x 1 inch verticals with 2 x 1 inch verticals nailed along the back to make a T section to brace them and made them rigid. The top, bottom and intermediate rails were to the same detail. The internal walls were formed out of2 12 ins, thick solid reinforced plaster premade to order by Castley Bros.

These were fixed onto 212 ins x 1 inch strips ramset to the floor and the plaster panels were jointed to each other with more plaster. A brick skin was laid outside these walls to form a veneer structure.

A large chimney facing both into the restaurant and the living room formed the centre of the house. The chimney was erected by a single bricklayer while the girls were paving. He was a shy man and he had a superb view of them from his scaffold. His main trouble was that he was perpetually in danger of falling as he stared fascinated and listened to their outgoing Eltham-style talk. He only made one private remark to Betty. He looked down at her endearin~ly and said: 'Sausage'.

It has been my privilege to watch a great deal of new building lifestyle come into being and it is my confirmed opinion that overall the girls have been better and more adventurous at it than most of the men. Betty and Margot, Yvonne Jelbart, Faye Harcourt, Corrie Vermeullen, Sonia Skipper and many other crowd into the mind. It is often harder to recollect what their opposite male numbers looked like.

Women builders were no flash in the pan. Today, in many districts across the country, they are standing alongside their men in the great adventure of building their own shelters and developing their own lifestyles.

The greatest problem I have encountered in recording the social history of Eltham and its people has been to contain the wealth of material within manageable proportions.

I started off in a light-hearted manner by describing my earliest memories. For the first three or four years this was easy because they were fairly general in nature. Then the society started to sub-divide into groups. There was Tim Burstall and his people, Clifton Pugh and the Dunmoochin community, and several important individual developments that were springing up in various places. The two factors that bound us all together were the mud brick building and the new awareness of the power and significance in the indigenous Australian landscape.

I claim to be the only Australian landscape person over fifty years old who has never planted a pine tree. This was because my uncle, W. D. Knox, who was one of the later Australian impressionist painters, would refer to their sour-green colour when I went out with him as a boy as he painted around East Ivanhoe in the 1920s. I could see exactly what he meant. They rapidly neutralized the marvellous natural Australian landscape sense of light and colour.

Another influence on my early life occurred when my family used to holiday at Belgrave in the Dandenongs at about the same period. We rented a house in one of the remaining mountain ash stands that generated a sense of peace and melancholy power. The great trees stood like a collection of medieval spires on the steep slopes above the village.

Coupled with the strong smell of cinnamon wattle (leprosa tenuixfolia) that was indigenous to the area, they caused such a hypnotic effect on me that I would sit down among them for hours at a time. Even today, if I go back to Belgrave, which has greatly changed, the faint recollective cinnamon fragrance recalls my early boyhood.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >