Living in the Environment, Murphys Creek Homestead

Murphys Creek Homestead

Author: Alistair Knox

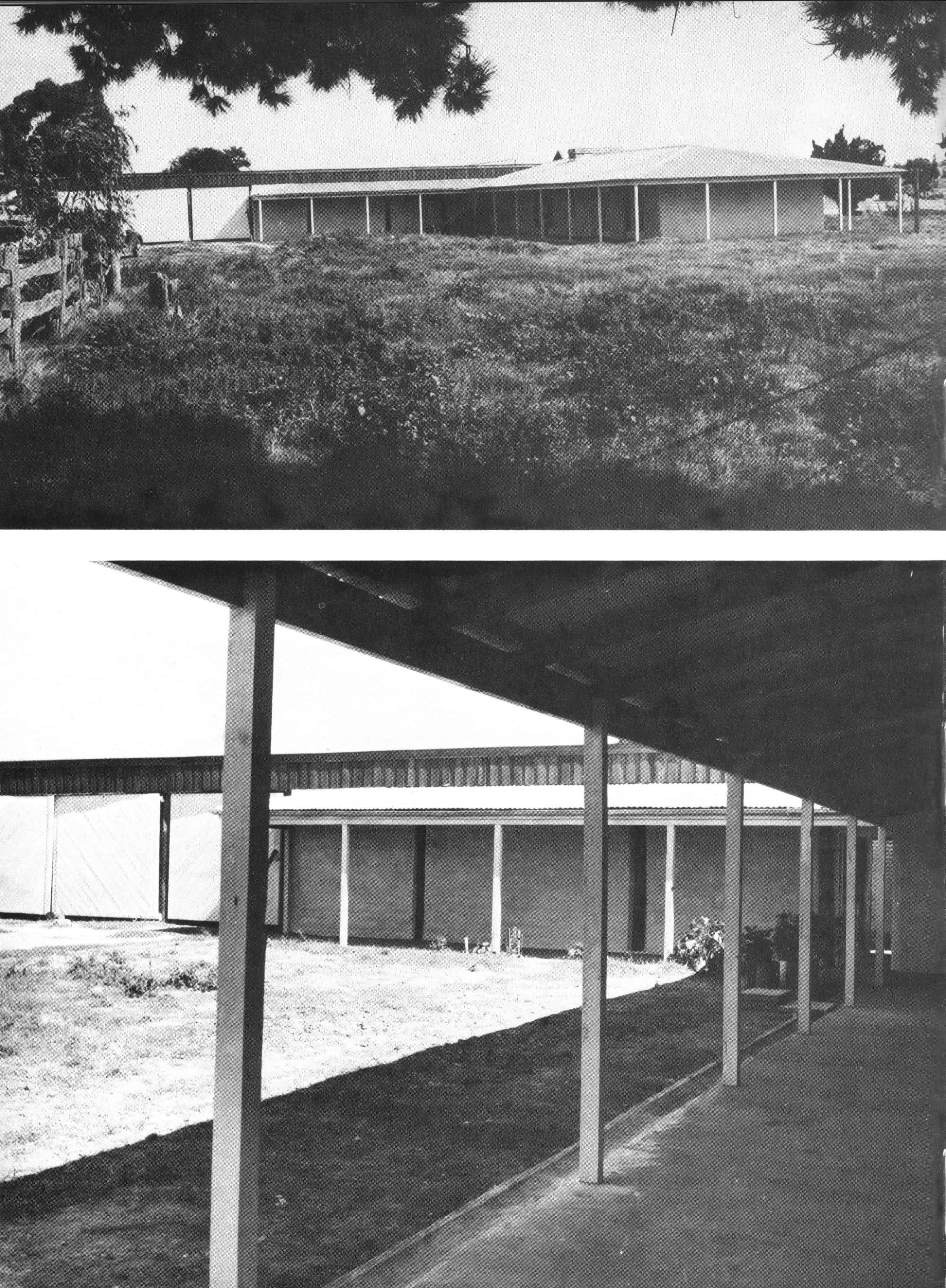

Above top: The Murphys Creek homestead, 1949.

Above bottom: The implement wing and back verandah

Above top: The Murphys Creek homestead, 1949.

Above bottom: The implement wing and back verandah

Those five environmental years that produced the modern Eltham climate for living had repercussions in other places. I sometimes received samples of soil through the post made into miniature blocks of adobe asking my opinion on them. Letters from other countries showed how this simple experiment had inspired those who were frustrated by the lack of normal building materials and driven by a necessity to find a suitable shelter for living in.

One day I received a phone call on behalf of a lady who had lived all her married life in a farming settlement in the middle of Victoria. At that time, the architect Robin Boyd used to write for the daily papers articles on mud brick building from the material he received from me. It was this that stimulated the enquiry as to whether a new homestead could be built on her sixteen hundred acre farm at Murphys Creek, located halfway between Tarnagulla and Moliagul and a few miles east of Dunolly.

These towns were the basis of the greatest alluvial goldfields of Victoria. 'The Welcome Stranger Nugget' unearthed at Moliagul a few inches below the surface, is the largest piece of gold ever found in one piece. Even after it had had bits broken off before it got to the bank, it still weighed more than 2200 ounces of pure gold. The gold had long since gone and the district became one on which the 20th century never truly dawned.

A few farms set a mile or two from each other were the only signs of habitation when I first visited the art~a. They were simple wooden or mud l2rick buildings surrounded by scattered trees and a heterogeneous collection of outhouses. The slightly undulating landscape gave unmistakable signs of its immense geological antiquity, and Mount Moliagul rose about a thousand feet above the surrounding plain in solitary grandeur. Its silhouette was like a sleeping lion carved in granite.

The war brought prosperity to Murphys Creek farmers because of the high price of wool, which at this time was equalled only by the high levels of taxation. It was essential to place these large wool cheques to farm developments of every kind, rather than see it fall into the hands of the rapacious Commissioner of Taxation. The existing farm had bitter-sweet memories for its widowed owner. There had been years of struggle and isolation. Now was her great chance to leave the place better than she found it, and the only material available for the work was mud brick.

When I first visited the site one Saturday afternoon, I felt a sense of forlorn loneliness. The existing farmhouse was quietly disintegrating as though it had given up any hope for its life. The oldest parts had been made from vertical saplings set into the ground and plastered on each side to form a type of wattle and daub. The white ants had attacked these saplings and they were eaten almost through at the ground level. Other buildings of later time were in weatherboard, but these had lost their paint and the whole farm had a sombre derelict character about it. The main house was surrounded by an incredible array of small buildings, apple sheds, shearers' quarters, dairies and the like, and in the distance the shearing sheds, sheep yard and the implement buildings all bore the marks of struggle, hard times and the pioneer battle.

Inside we found the share farmers who were working the farm. Reg Heather was short, solid and weatherworn with a radiant smile and a high-pitched voice. His wife was a soul full of rectitude and good works. They laid before us what later became the tradition of our rebuilding activities - the afternoon lunch. This meal, set between th~ main meals of the day both morning and afternoon, provided a galaxy of home made cakes and scones, clotted cream and jam that quickly took away the first impressions. The kitchen seemed to have been laid out and designed in a way to make it as dreary as possible. There was no sink and a tin wash-up basin was placed on the table for that purpose. From this position you looked out through a small back window onto what had once been a small orchard and a vegetable and garden area, but the weeds had taken over and now it looked desolate and uninviting. The well-worn lino was obviously a continual source of cleaning because of the dirt trapped in by the men with their hobnail boots. The fire stove had been built in so that it was almost impossible to see what was going on when you were cooking. There was no electric power, yet even this gloomy room was something of a bastion against the power of the outside landscape that afternoon.

Arrangements were made to design a building using what was available from the out-buildings and the house, and transferring them into a new mud brick structure that would also incorporate farm equipment and clean up the site generally. It was certainly not before time. I estimated the quantity of usable roofing iron and timber this would provide and how it could all be put in hand.

On returning to Melbourne I laid the scheme before the mud brick making group. Three volunteers resulted and they set off for Tarnagulla and Murphys Creek armed with picks and shovels and the determination to make a lot of money quickly and to buck the system at the same time. Arrangements were made to dig the required soil by hand in a pond near the disused pig pens. This hole was about a foot deep and the soil was to be broken back into water that was placed in it at that level, similar to the way it had been done in Eltham in the time of the water shortages. I returned to Melbourne feeling that here was a start of a great adventure in post war building. It didn't quite turn out that way. I still worked in a bank in the city, waiting for the position to ease so that I could go into design and construction full time. Two of the men concerned have since become well known environmentalists - Neil Douglas, the artist, and Gordon Ford, the landscape architect.

The first attempt at making mud bricks at Murphys Creek was a calamity, but it was one of the links which later forged their characters and. approach to the total landscape. Two weeks after starting, a telegram arrived from them which stated, 'Bricks already made, now so badly cracked, have ceased work, await your arrival Saturday'. As I read the telegram, the farm scene with the scattered out-buildings and the pig pond etched itself on my mind with a melancholy foreboding.

When I stepped from the car with the owner's daughter, the next weekend, the sight of all those cracked and disintegrating bricks passing before my eyes was like a dark cloud moving across the sunny afternoon. Gordon Ford referred to it at a later time as the 'boulevarde of broken dreams'. The brick makers had been working up a healthy hate for me in the shearers' shed while they 'awaited my arrival'. The owners were naturally perplexed, and I was working out a compromise to keep things going, which was not easy to do. The residents on the adjacent farms had seen lanterns moving over that silent landscape till all hours of the night and it was reliably reported that no one had ever worked so hard in that district since the gold rush. W!J.en we had returned to friendly terms again, they told me how exhausted they would be when they came in late at night. Then they would be wakened at about 3 o'clock in the morning by cocks crowing in the fowl shed next door. They decided to de-rooster the yard by grabbing the cocks that crowed and placing them in a disused country outhouse, leaving them there until daylight so that they could get their required sleep. One time they forgot the captured birds for about four days. Suddenly they remembered; when they opened the door of the lavatory, the once noble cocks that had caused them so much trouble were skinny and emaciated, and the Heathers were always puzzled as to what had happened to their condition.

I did eventually effect a solution to my problem. The brick makers would be paid some money. The owners became more determined than ever to proceed, and a certain Archer Hancock, who had actually built in mud bricks many years before, was to supervise the making of them. They had gone wrong in not sticking close to the surface as planned. They felt they were getting good sandy content arid clay soil as they went deep down into the ground, and formed a series of caves and brought the material up from the bowels of the earth. They gave names to each of these holes such as 'Tea Leaves' and 'Pigs' to keep themselves amused while they went through the prodigious efforts of wheeling barrow load after barrow load of material onto the natural ground level to form into bricks.

It turned out that the material was rotten granite and felspar that broke up on exposure to the air, no matter what you did. This was sad enough, but when I examined the pick that Cyril Jacka, the third member of the trio had used, I found he had ground some inches off its length by the sheer effort of driving it into the ground an almost infinite number of times during those two weeks.

The second attempt was a complete success. The top soil was a gritty sandy loam which was disced to a depth of about eight or nine inches. The grass was automatically chopped up into it and the whole was pushed into heaps for easy handling. These top soil bricks were not as strong as the clay based ones, but they were very adequate. They slumped a little as they were slipped out of the mould and when erected they gave the character of old stone walls. They were easy to lay in the same top soil that was used for mortar. Being a farmhouse there was a request for smooth wall finishes internally. The tenacious top soil to which some cowdung was added gave a characterful finish, not quite as smooth as plaster but it had more quality and it looked truer.

Archer Hancock, who supervised the work, had lived all his life in this remote district. He had only been to Melbourne once in his sixty years or more, and to the provincial capital, Bendigo, four times in the past twenty-eight years. What he lacked in travel, he made up for in wonderful common sense and general ability. His father had been one of a family of six sons who had all emigrated from England and all been stone masons. His father and mother had come overland from Adelaide many years before in a horse drawn dray, accompanied by seventy Chinese who were no doubt destined to work on the goldfields. His farm had several beautiful little buildings on it that had been erected by his father. One was a combination of clay and granite that glistened like gold in the sun. Another was in mud brick, which he called 'Gyptian Brick', apparently because of its relationship to those bricks being made in Egypt some 3000 years ago. He would smack the walls with his great hand and almost shout with glee as he spoke of the struggle of the old days. His own father used to go to work on horse back and on his way home he would pick up a couple of stones by the wayside, probably unearthed by the alluvial gold mining, and put them in his bag. One day he fell from his horse and from that time never walked again. The family set up a vegetable run while he lay on his back for eighteen months. Then they got him up and carried him out each day into the garden where he sorted the produce. After another two years he fashioned a short handled spade. He would drag himself around the property with this implement and dig post holes. That indomitable spirit certainly sat on his son as he arrived in a light horse-drawn cart on the brick making site with his cap set at the correct angle. You knew the king of that community had come.

There were periods of rain during the mud brick making process with some disappointing results for the makers. They would lie on their beds in the shearers' huts and shake malevolent fists at the iron roof and the swishing sound of the rain. The share farmer, Reg Heather, told me of this in his high uncomplaining voice with a little chuckle. 'It's too bad for the boys', he would say, 'but we want the rain'. The boys took some time to see it this way, but gradually the power of that landscape dominated everyone and everything and we were all humbled and elated by the privilege of working in it. Reg's philosophy did not come by chance. He had spent eight years on a farm in marginal mallee country and suffered seven successive bad seasons. The eighth produced a bumper harvest but it was in the middle of the depression of the 30s and he couldn't sell the wheat. He and his wife walked off it with literally nothing but what they wore. He wasn't bitter, just realistic.

Arrangements were made to pour concrete slabs and erect implement sheds from the second hand corrugated iron salvaged from the old buildings. The roof was supported on iron bark poles taken from the forest reserve on the farm. The poles were cut off at ground level to reveal timber of a colour identical to the red ironstone country in which they grew and actually flourished. Mud bricks were then laid between these poles so that mud brick and timber walls were formed. The house itself which was fairly large, rose from the ground to plate level in nine days. A contingent of mud brick workers arrived and started working forthwith, and continued for twelve hours each day every day until the job was finished. Every morning Archer Hancock would appear in his cart at about eight o''clock full of excitement and expectation. Even the horse seemed to catch some of this spirit and the cart would spring through the farm gate and pace down the drive and onto the site as though it was in the grand parade at the Royal Show. What a wonderful inspiration he would have been for this second generation of mud brick builders, if he were still alive.

Mrs. Heather's morning and afternoon lunches had to be seen to be believed.

The scrubbed kitchen table was laid with the best table cloth. It was covered with innumerable plates of scones, cheese, cream and jam, sausage rolls, pies, lamingtons, mince tarts and napoleons. Archer's eyes shone like blue sapphires and as he shouted and laughed over his food he would spurt crumbs from his mouth with such force that it was almost necessary to take cover. 'Yes, Sir', he would yell. 'The blood house, the blood house', which was what he always called our mud brick building. At that time it was a simple and hearty scene. In retrospect, this quality of human integrity is very moving. Most of the builders at that table have since become well known men of special abilities. Caught in that in-between time of the peace and the corporate state, they gave it a memorable quality. Only one came from the building trade. They would all subscribe to the spirit of the humble mud brick as being the catalyst for a 'nobility of intent' in other fields.

The Heathers had grave doubts about the house at first. They said nothing, but watched carefully. The concrete floors· had been overlaid with bitumenous compound, and the builders were half indignant and half hilarious when they caught the Heathers checking the levels with torches at night.

The work went ahead in spasms of about six weeks, separated by about the same period waiting for the next wool cheque to arrive. The old buildings were demolished one by one and recycled into the new. We finished up with almost exactly the right number of sheets of corrugated iron. None had to be bought which was essential. It was doubtful if any would have been available at that time.

Then there were those occasional hilarious nights when we all set off for Tarnagulla six miles away, crammed into the Heathers' utility. This ancient town was literally subsiding into the past. Many of the walls of the buildings in the main street had adopted leaning postures. Their verandahs sagged, and some houses had already been removed altogether. There was a railway station which was then used only about once a week except in harvest time, when it became very busy. There was one hotel remaining out of the original thirteen; it was inevitable that it should have been called the 'Golden Age Hotel'. It was like most other buildings in that vicinity being in more than one piece. The bar, lounge, dining room and kitchen were on one side of a ferny alley way with the sleeping quarters on the other. It was a fretting pile of ancient hand-made bricks and slowly rusting iron roofs. Inside, the ceilings were lined with the traditional matchboard planking. One of the builders, who has since achieved fame as a Shakespearian actor, would reduce the hotel licencee's father to tears, as he sang 'Galway Bay' and other Irish songs to the pianola with melodramatic effect. The old man would shake his head with the tears' trickling 'down his cheeks. 'And it's all so true', he would sob.

Further along the street, which had been planted with alternating ironbarks and lemon scented gums, stood Reid's Stores, an extraordinary timber monolith from a more salubrious age. Mr. Reid presided over this establishment with a female assistant and a couple of men who looked after the groceries division. His eyes lit up when he first saw us and he arranged for orders to be sent out to the farm. The long wide kauri counters carried a heterogeneous combination of cheese and sausages, bales of cloth, boots and hardware, set up one against the other in promiscuous disorder. There was a series of huge shutters which protected the windows of the buildings from the outside. Each night the unfortunate assistants had to stagger around with them and clamp them home over the glass with iron bars and locks. Mr. Reid's mind no doubt went back to the past when the sounds of the drunken orgies of the miners echoed up and down the now deserted streets. Only the stars still glinted and winkeq in the fantastically clear, cold atmosphere just as they always had. Around the corner the main road reduced to a winding track that ran for five miles through the old alluvial diggings to Llanacoort. The primordial ironbarks dominated this silent night scene where the whole of the surrounding ground had been turned over and over in the pursuit of the gold in those romantic days.

Tarnagulla had once boasted six banks, but only one remained open at this time. It was notable for a large factory chimney mounting up from one corner of the building. The reason for this odd commercial enterprise was that it denoted a gold-smelting furnace inside. The nuggets were brought in in such abundance that they were melted down into ingots and sent back to Melbourne under escort.

As the building neared completion and the changeover from the existing house had to take place, the Heathers arranged to go for the first holiday they had ever had. When they returned, they were bowed into the new homestead by the workers who stood by with bated breath to watch the result. The Heathers had experienced too many battles in the Mallee to accept anything on face value. The fire was lit in the low fireplace in the kitchen beside the firestove and Reg Heather found himself resting with his backside against it within five minutes as the smoke roared up the chimney and the whole room lit by the flames took on the subtle effulgence of firelight.

Mrs. Heather's sink was situated so that the occasional vehicle that passed by on the road could be both seen and heard. Within an hour the morning lunch took on a new meaning for everyone. The physical effort of creating a quality of life they had never experienced before, -mingled their spirits with the workers who had become deeply involved in the primeval landscape and transforming its earth and reclaimed materials into a simple living creation. As doubts turned into joy, we all realised that the truly simple can become the truly profound.

It was not long before Reg's trousers had worn a kind of pattern over the kitchen fire stove which he stood beside with joy saying, 'When I first saw it, I thought it was a fool of a thing( but it's the most wonderful fireplace I have ever seen'.

Finally the house was completed and the yards cleared up and time for departure came. Everyone of those sophisticated workers found themselves unashamedly in tears, and so indeed were the Heathers. They had both discovered a new relationship with each other and with the landscape. It was human ecology in action.

Back in Melbourne the widowed owner of the farm was informed that she had set alight an inspiration in the hearts of men that she had never expected. Real mud brick building has this supreme quality. It can combine materials and people in a unity when it is used with a 'Nobility of Intent', that no other materials can achieve. This is because it can be done by ordinary people who have not lost their vision with long years of apprenticeship and drudgery.

There were many diverting incidents that took place during the building.

One that recurred several times would happen when I would telephone Murphys Creek. The call had to go through three Post Offices, the last of which was Murphys Creek itself, situated in a farm building which stood in the landscape about half a mile to the north. The Post Mistress would call the house, but if the Heathers were out the sound would not penetrate the solid and insulating earth walls. After some minutes of fruitless effort she would step outside and beat manfully on a kerosine tin in an endeavour to attract their attention. If this failed she would send over her young brother on his bike.

Another incident which sent us into paroxysms occurred just after the Heathers had moved into the new house. Some parts of the old building were still standing, including the wall that contained the kitchen back door. Mr. Reid's grocer men called next day with the order and knocked as they had knocked for twenty years. Being unable to attract attention, they opened it to discover that the whole of the rest of the house had been taken away and they were looking at a few floor joists and a distant view!

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >