Living in the Environment, Post-War Architecture and Natural Building

Post-War Architecture and Natural Building

Author: Alistair Knox

Australia's environmental building school started in Melbourne in the 1940s because the Eltham train got me back in time to discuss earth building with the shire councillors. It could not have happened elsewhere.

The building regulations in New South Wales, for instance, were in part under control of the Police Department. What chance did planners have in that state? They retained a very Captain Bligh attitude to innovation and inspiration in standards and design. I suppose it sprang from the early days of the colony when Mr. Bigge came over with the idea of controlling Governor Macquarie and his ex-convict architect, Francis Greenway, from building what he believed were megalomaniacal monuments. Possibly it may have been necessary in those faraway days if one recalls Greenway's flights of fancy.

Once commissioned to design an aviary for the Governor's daughter, Greenway finished up with a plan more on the style of the Crystal Palace than a bird cage. They must have been good times, nevertheless, despite all the sufferings of the convicts and the battlings of the community. The options were wide open and in terms of the imagination the sky was truly the limit.

It was different in Melbourne. There was a lively architectural school with men like Robin Boyd, Roy Grounds and Bob Eggleston among the instructors. The shortage of normal materials and desire to be original however, introduced a style of architecture reminiscent of fowl sheds. It was called the thin line. It most certainly was thin. The roofs were called monopitch which is an architectural way of saying skillion. Eventually the line became so thin that it disappeared altogether and was never heard of again.

It was a unique position to start on indigenous design, because post-war society had had to adapt itself to a changing lifestyle during previous years and now that peace had returned, it wanted to be led into new ideas and to 'have a go' at the way that lay ahead. At the same time, the new techniques that started to become available tended to become an end in themselves. If it was new, it was good, was the thesis. Economics transcended quality and spiritless, impersonal planning resulted.

An important inner character of genius lies in its quality of timelessness. The work must transcend fashion, and exist in its own right for succeeding generations. The greatness of men like Shakespeare, Beethoven and Rembrandt would have been outstanding in any period of history because of this characteristic, despite the fact that the time and the man often do combine to become part of human history.

In this outpouring of techniques, Melbourne's first glass house occurred. It was a modest affair designed by John La Gerche of Heidelberg at the east end of Collins Street, but many that followed it were immodest because of the indecent exposure of their structural components and of their shape in the landscape. They were slavish imitations of the cubist international style, so-called. It was these which caused Bertrand Russell to say that he could look out of a hotel window in any city of the world and not know what country he was in.

The influence of climate on architecture should be apparent from country to country. The trouble was that the climate of the world in the 1950s was economic and not elemental. The poet and architect, John Betjeman stated that Australia was the only country in the world where, even in big cities, he was aware that nature was still more powerful than man.

Australian architects should have seized this opportunity to revive the offensive Australianism of their fathers. The scene was set for a national style to emerge so that we could build 'with style rather than to a style' as Frank Lloyd Wright would have said. Instead, an endless repetition of glass-faced structures commenced to transform the human scale of our major cities into commercial canyons. Their only reason for being was to crowd more people into a smaller ground space than heretofore, to the rejoicing of the Central Business District, the willing tool of the internationally controlled corporate state.

There is scarcely one building in that post-war era which expressed those indigenous Australian characteristics that both Greenway and Griffin understood so well; a timeless proportion and an understanding of sunlight and shadow as architectural factors. These and the quality of light were still all there for the taking. If city structures had expressed some sculptural asymetric cantilevers on their facades and the sense of primitive power in their masses alone, Australia could have claimed a special place in architecural history, instead of leaving the field to that destroyer of building history, Mr. Whelan the Wrecker. The variety and interplay of sunlight and shadows over such facades would have spoken of the timeless land and the Aboriginal interpolations of the original inhabitants.

It was in 1949 that I first came to know and appreciate Dorian Le Gallienne. He was the one person who did not strive for newness, but for truth. He was a memorable composer and a music critic. In conjunction with his lifelong companion Professor Dick Downing, he asked me to design and construct a weekend house in mud brick for them on the river at Eltham. During the next fifteen years I designed and built four different structures on this property, and at the same time found in an increasingly significant way the power and the spirit of the environment.

Their twenty-five acres of land ran some quarter of a mile from the road to the Yarra River. It was a restored wilderness area. It had apparently suffered from timber-getting earlier in the century, and also from bushfires, especially in 1939. Copses of wattles had germinated after the fires. They intensified the bush but reduced the scale. The landscape had restored a mystery similar to the original, but without the ancient dimension of it.

The South Western Eltham boundary, the Yarra River, was in those days largely a wild landscape, especially on the Eltham side. It was the haunt of the platypus, the black wallaby and other animal life, together with a tremendous variety of bird species. Here again, when we walked through it on those late Saturday afternoons, listening to the cranking cry of the gang-gang parrots, the subtle pink and grey would repeat the eternal motif of light and colour. It was summer time and tiny flecks of cirrus clouds were suspended in the atmosphere that seemed a thousand miles high, as the large pale moon rose over the Dandenongs to the east.

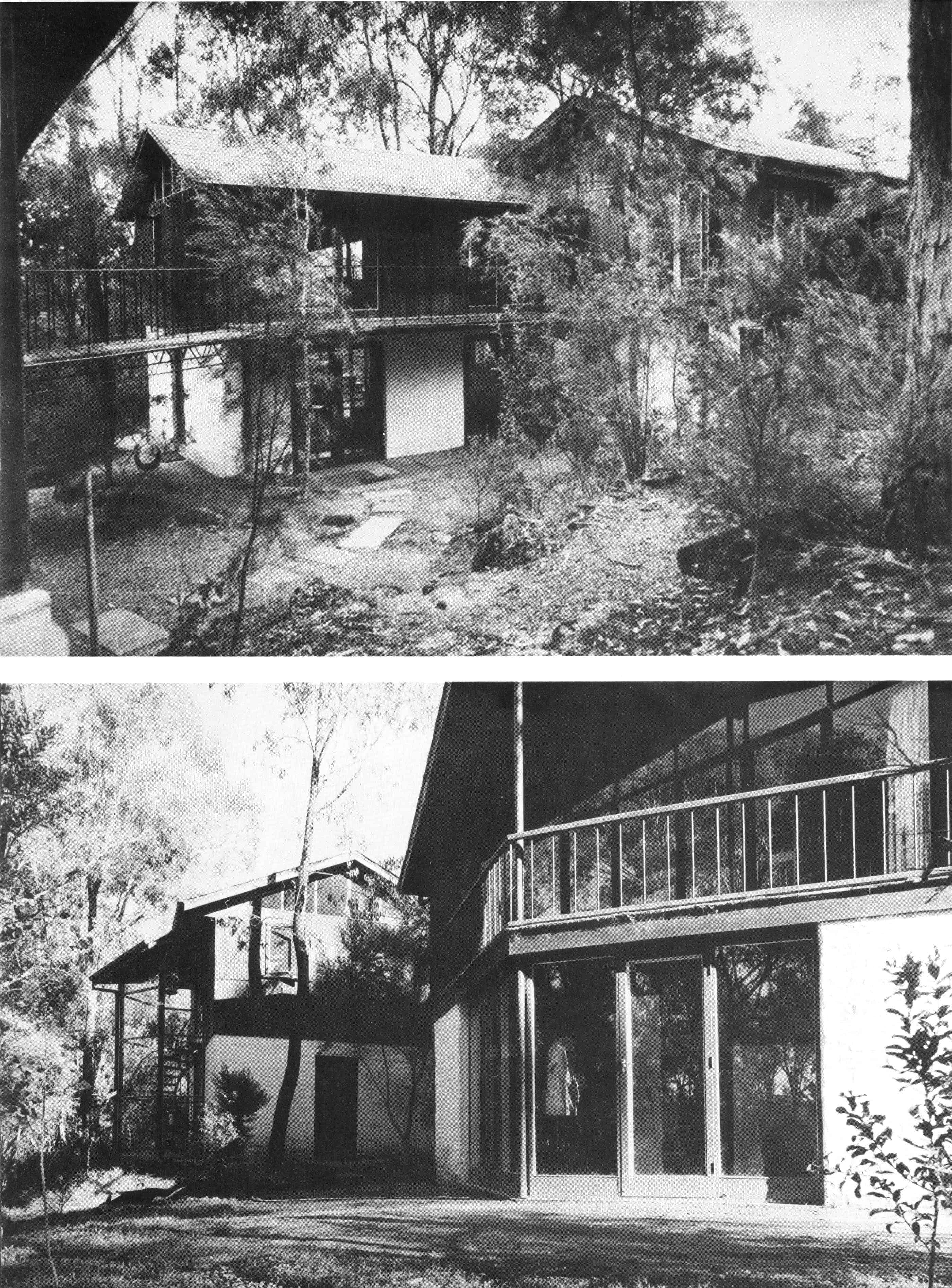

Above top: The Le Galliene-Downing courtyard. Landscape by Ellis Stones.

Above bottom: The second and third wings

Above top: The Le Galliene-Downing courtyard. Landscape by Ellis Stones.

Above bottom: The second and third wings

Dorian and Dick had a comprehension of the total landscape in its relationship to humanity that I had never before encountered. In addition, they had an ability to see quality where others could not. Like everyone else at this time, I was itching to be clever in design. It was Dorian's explanations which caused me to slow down and think in simple, timeless proportions - to relate to the powerful landscape, rather than to try to outdo it.

The Busst house had been a real success and I was anxious to do more flexible design. However, Dorian settled for a sketch of supreme simplicity. This was fortunately exactly right in proportion. The shape was to be the key of all that was to take place during the succeeding years. The design was a simple rectangle of mud brick with a concrete plinth on top of each wall. A system of rafters was set into these concrete beams to form a series of scissor trusses. I had seen something of this character in an old church in Maldon, the gold mining town we used to pass through going and coming from Tarnagulla and Murphys Creek. It allowed the building to have an apparently unsupported ceiling ridge. The whole of the interior of the house could be comprehended at one time. There were vertical divisions in the building, with a kitchen and a bunk area and a shower, but they only rose to seven feet. Clerestory windows at each gable end looked out on the marvellous landscape. One of Dorian's special abilities was to leave nature alone except to intensify it and let it come right up to the doors of the house.

The internal lining walls were two thicknesses of six by one millsawn hardwood, laminated and nailed together by staggering the joints. The panels were held top and bottom by timber moulds. It was a primitive approach, reminiscent of the pioneering days. I have kept this idea going on quietly ever since. Now a large proportion of our timber work is either millsawn or adzed in even the most respectable architectural buildings of 1975.

This building was not really occupied for some years. As it neared completion, the owners went overseas for four years. Dick Downing eventually returned from the elegant and delightful city of Geneva because he could no longer stay away from the silent mystery and longing of the Eltham bushland. His return necessitated a second wing, which consisted of a five-sided study on the ground level, and two bedrooms and verandah set above it and springing back onto the hillside, so that entry could be made at ground level to the upper level. Access was gained to a courtyard complete with its own creek and bog garden by passing under tbe upper floor level where it joined the excavated hillside.

Ellis Stones, the landscape architect, was responsible for the landscaping. At the time he was on crutches because of complications from a wound he had received on the first day of the Anzac landing in 1915 in the First World War. After some persuasion, I arranged for labourers to do the work for him while he directe'd operations from an armchair. As the boulders were being placed in position to his instructions, he was unable to keep his seat and would leap up from time to time, hop to the scene of action on one leg, and start using his crutch as a tool ramming back the soil. Such an enthusiastic attitude to the production of his ideas was possibly one of the reasons why Ellis Stones was so long in being recognised by the more 'professional members' of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects. That solemn body which attained professional status in 1966 regarded any applicant for membership who had not gone through some school in England or held no academic qualification in another discipline below that of professor, as being an unacceptable type of person for their ranks. It did not seem to matter that Ellis had been working in true Australian landscape design quite alone, and that he indeed conceived its spirit and principle about thirty years earlier.

When he died in 1975, aged 79, he had just reached the height of his powers. He died quietly in the evening after a long day in the field, restoring the Salt Creek into a natural waterway, which the Metropolitan Board of Works had been itching to barrel drain for a considerable time. Had he lived another five years, this modest, witty, poetic man would have become an outstanding worldwide landscape figure. He had really succeeded in beating the system in all its forms single-handed, and produced an Australian art form that has swept the country.

One of those labourers was Gordon Ford, his best pupil. It was here he discovered his primary feelings for the indigenous landscape through his association with 'Rocky' Stones, as he was always called.

Clifton Pugh, the artist, was now on the threshold of his career. He wanted to earn some money and volunteered to make mud bricks for the new wing, and build the house t6 the first floor level. As the bricks were made on site in those days, it was quite a relief when someone responsible like Cliff volunteered for the job. Carpenters were employed to construct the top level over the mud brick section. The Sibbel brothers, who have since become large scale designers and builders with a wide reputation, worked as foremen on that job. Environmental building is a catalyst that draws together a wide variety of talents, and interests.

Dick and Dorian would have breakfast on the terrace between ten and eleven and I made it a point of being there at that time as often as I could. With one or two others, I would sit around drinking expensive tea from a great silver teapot. We would contemplate the wistful beauty of the landscape. Dorian's penetrating analysis of its components and impact were a revelation that opened up its unfathomable depths. He had the ability to discern value in things and in people of which I had been hitherto unaware.

The teeming birdlife was all around us. Yellow-breasted robins and grey thrushes picked up biscuit crumbs. Parrots of all kinds flew overhead with whirring wings and raucous calls trying to drown out the magpie's carol and the bellbirds calling up from the river's bank. At these special times, I was discovering greater depths of basic principles of environmental design and inspiration. We would laugh at Dorian insisting that Dick would eat his porridge standing up and walking round before we came to the hot buttered toast and the Oxford Vintage Marmalade. There was time for such things in those days of lost opportunities. They were the last times for years that I had the liberty to sit and meditate 'on the options of life.

Clifton Pugh had the natural desire to build that is common with all artistic and imaginative people. His constructions at that time were noted for their speed of erection, rather than for being plumb and level. I told him that those technical requirements were essential in this job and I had the pleasure of being present when the carpenters ran their levels over the work and pronounced it to be true and plumb. A slight shiver of relief went through him. 'It's the first time it has ever happened', he said quietly to me.

It was a few days after this, before the timber construction had really begun on the next floor, that Cliff asked me if John Howley, a fellow artist, could help him render the mud brick walls. Next day I came out at the usual time to see how things were progressing. It was a cold misty morning and as I walked down the hill I could hear John Howley shouting ecstatically from the bowels of the five-sided room. When I was able to look down into it from the bank above, I found that he had stripped himself completely naked and was snatching handfuls of wet earth from the concrete slab floor and leaping up at the walls to smear it on at the higher levels. His long black hair kept falling over his eyes, and he would occasionally slap a handful of yellow clay onto it to keep it in place! His body was bluish pink and steam was literally rising from it as he exulted in his first experience of earth building.

Cliff's introduction to the building scene occurred around 1950 when he had bought land about two miles beyond Hurstbridge for a few ·dollars an acre. One sunny morning we set out together for his holding at Cottles Bridge, my Matador truck loaded to the gunwales. It was reject material from the Templestowe project, which was my first major complex of buildings in the landscape. His place was later to be called 'Dunmoochin', but at this time I dubbed it 'Hunger Ridge' because I guessed it ran about a lizard to the acre. 'This is where I will build', he said near the top of a hill we were ascending, indicating a point on the side of the track. Secondary growth of stringy bark about two or three inches in diameter were the only vertical elements in that landscape. We emptied out our load and returned.

Cliff rang me three weeks later. His voice sounded fairly remote, but quite clear, over the telephone. 'I've built that house, AI', he said simply. I was stunned. I had been working on the Templestowe project of four buildings on an orchard, and the normal building time in those days was about nine months per house.

'I've got the phone connected too', he continued. The average delay for telephone connections varied from eighteen months to three years because of postwar backlogs. I asked him how it had happened. 'Well, I was working on the house one day', he explained, 'when a bloke came up and asked me if I wanted the 'phone on. I explained that I didn't have anywhere to put it at that time. He said, "Never mind, we are trying to get thirty subscribers together to start a 'phone service at Arthur's Creek. I'll bring your handset tomorrow and we can put it in the fork of that tree and you can throw a bag over it"

I was anxious to see what Cliff had done because the material I had given him was mostly six by one and other odd sizes for structural work, and was all very second rate quality. The house was there alright. It consisted of euycalypt saplings set into the ground, with wattle boughs and other thin branches set horizontally and nailed in between these verticals. The building had an earth floor. There was a doorway and a second-hand window, which from recollection had cost thirty cents, built into the earth walls. The roof was flC\t. Four by two members that I had given him were erected as rafters and the six by one as a deck. A single thickness of malthoid had been nailed over the deck with clouts. Inside there was a mud brick fire place that seemed to let some of the smoke out of the room and the remainder hovered like a cloud in the upper reaches. Some broken-down flintlocks hung over the chimney and were just discernible through the smoky haze.

He explained that he had observed how the old miners built, and had used their methods. Everything had gone as planned until he realised he had no water to make mud to render between the wattles to create the wattle and daub character. At the appropriate time a heavy deluge of rain ran off the roof onto the ground and turned the yellow clay into the most delicious mud. They rushed out and ladled on it handfuls to form the sculptured walls.

Cliff had a really good athletic figure. He took to wearing a strong man's leopard skin garment and sandals, ostensibly for natural living and also possibly from justifiable pride in his condition. He would stride through the bush carrying a long-bow with a leopard skin quiver thrown over his shoulder to shoot rabbits. It was an interesting sight. Subsequently, he put his leopard skin away for two reasons. The first was that he couldn't hit any rabbits with the bow and arrow. And the second and final blow came when on one of his treks through the scrub he came upon two shooters armed with double-barrelled shot guns and the usual hunting paraphernalia. They caught sight of Cliff with his curly hair, beard, leopard skin clothing, sandals, and bow and arrow. With a gasp of horror they turned simultaneously and ran off at high speed. They have never been seen again. They are probably today regaling their grandchildren in the suburbs with stories about the twentieth century Wild Man of Cottles Bridge.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >