Living in the Environment, The Conflict

The Conflict

Author: Alistair Knox

Men who went back to their old sedentary jobs after the war soon saw their pre-war privileges had gone. The emphasis was now on the new business man, the sub-contractor, and not on the staff who recorded profits and losses for commercial companies or who dealt out money in the banks. Many had caught the delicious sense of freedom of the environmental life connected with soldiering and they had no intention of losing it again. They assessed that the hardships of that liberty could be transmuted in the sunlight of the times. It started the golden age that permitted the alternative of working hard at some new venture and becoming rich, which at that time was rare, or just quietly indulging in a relaxing life style.

The population of Melbourne was then a little over 1,000,000 and it was considered politically important to start a great migration movement. Two main reasons underlay this consideration. First, it was generally believed that a bigger population meant a greater security, and second, there was a real humanitarian concern for the numberless dispossessed and nationless refugees.

With the inability of the building industry to keep pace with a completely new attitude and demand for housing, the black market started in earnest. The Government had kept controls on petrol, rents, prices and many other commodities. There was money in abundance, and it was equalled only by the lack of materials and labour to get work done. The golden age began to suffer from a new form of greed and speculation. Land prices, although they were controlled, shot up because land could be bought with a little sleight of hand to beat the pegged prices. It was not necessary in those days to supply services or roads for subdivisions. All that was needed was a surveyor, an auctioneer, some street signs pointing around the open countryside, a marquee to hold the sale in, and the golden age of speculation had restored its character to what it was in the 1880s land boom.

There were no planning proposals for Melbourne, nor indeed a Town Planning course of any kind at any college or university. The peripheries of the city just started expanding with gay abandon wherever land was choicest, cheapest and most available - around its outer edges. It was a golden belt in a golden age.

Eltham was a little beyond this encircling movement. From Heidelberg you looked over that part of the Yarra Valley made sacred by the Australian School of Impressionist Landscape Painters - Roberts, Condor, Streeton, Withers, McCubbin & Co. It was here they first started painting the quality of light and colour, in the landscape which reaches its highest pinnacle along this meandering valley. The river which flows through it was called the Yarra Yarra by the aboriginals who had inhabited the land. The meaning of the name is 'everflowing' which in Australian rivers is less common than in any other continent. In general, Australia is a water hungry land. But not here. It is a long valley with steeply rising Mont Eagle on the west and the Dandenong Ranges on the east some fifteen miles away. To the north-east lie the Plenty Ranges, a series of low hills of a special character. They are worn down and timeless and dotted in the nearer reaches with the great river red gums in a broad savannah landscape. This is where the Shire of Eltham begins. It extends as far as the continental dividing range twenty miles to the north.

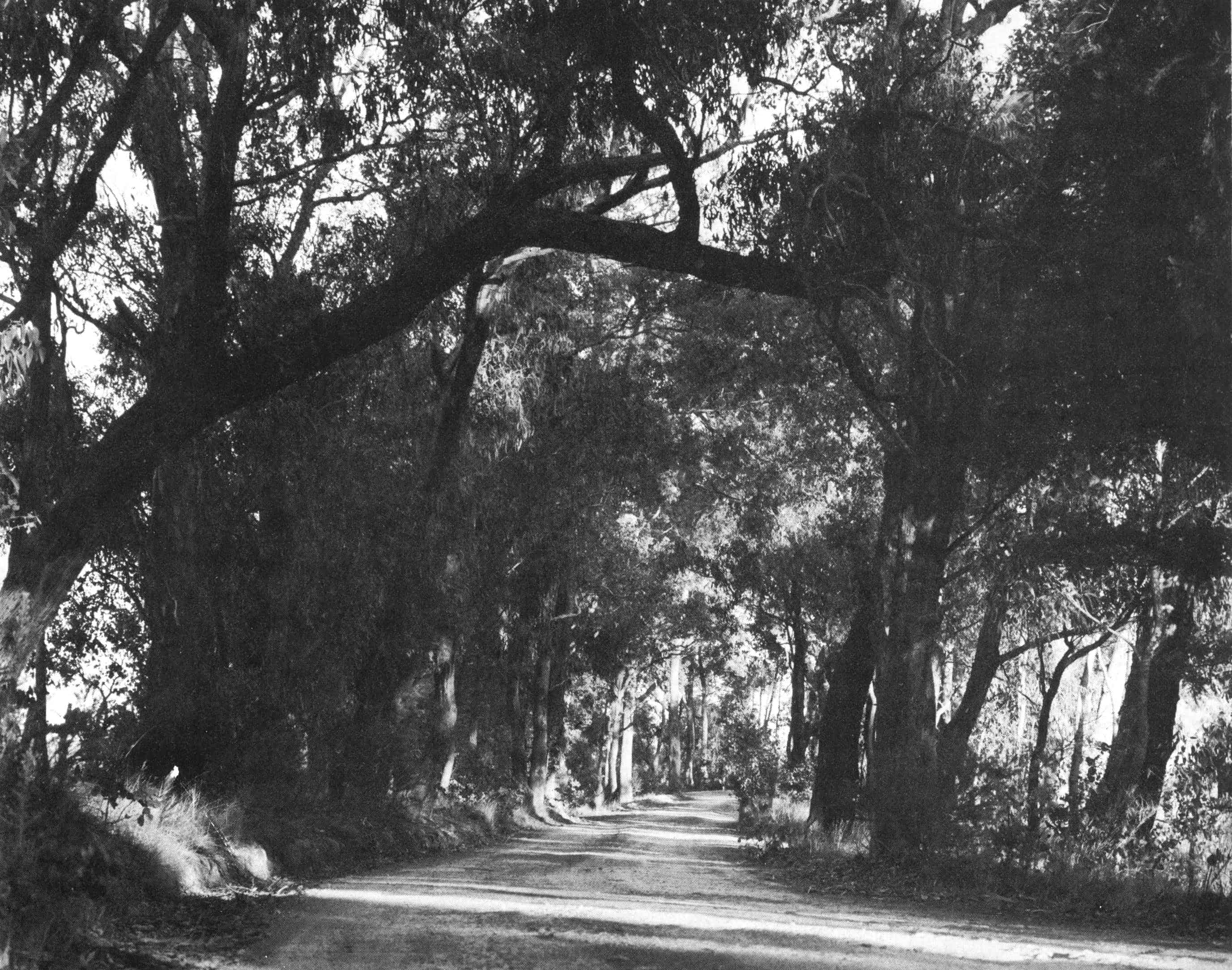

People in Heidelberg gazed out to Eltham and the Lower Plenty Ranges like Moses and the Children of Israel viewing the promised land from Mt. Pisgah. It was a mysterious bushscape of little bounding hills often half obscurred with mists in the mornings, and bathed in red-gold light in the afternoons. The moon that rose over them in the twilight in the east, and the evening star in the west, heralded the most beautiful nights that can happen anywhere in the world. By day the pale orange-pink gravel roads wind in and out of the mighty yellow-box trees. Their branches cast pale purple shadows on the roads that are speared with shafts of golden sunlight.

Century-old cottages with corrugated iron roofs and handmade brick chimneys stood here and there in an informal unity. Small farms and orchards interlaced the hillsides in another century tranquility. There were also some large houses standing in multi-acred grandeur along the banks of the river, but the total experience was identical to that which stimulated Australia's art movement half a century earlier.

The quality of light and colour engendered by the silver grey leaves of the eucalyptus, acacia and the low .scrub creates an emotional aura of well-being that touches the soul. The unbroken landscape expresses three basic factors: The first is that Australia is a land dominated by sunlight. The second is that it is water hungry. The third that water hunger has created survival consciousness.

The understanding of these three primary elements is the key to this timeless environment, of listening silence, eternal shapes and immutable power. The Eltham district had been a relatively dormant rural area for some seventy years although it began about fifty years earlier than that. It was on the southern edge of Eltham that Batman the founder of Melbourne made his great contract with the aboriginals. He exchanged knives, beads, blankets and trinkets for an immense parcel of land, Their meeting seemed to be agreeable and productive of good responses on both sides, The land they bartered for was, as Robin Boyd once wrote: 'an affable, muddy woodland, with bright blue skies flecked with white clouds that scudded overhead' ,

It was not a brittle, gold-blue scene as it had been in the initial spear-throwing contact that Cook had with the inhabitants at Botany Bay. It bore no resemblance to the Illawarra incident where Bass and Flinders escaped with their lives by trimming the aboriginals' beards with scissors.

This was a business transaction by business men, which I believe was influenced by the special characteristics of the climate and the landscape in which it was held. From that day onwards the State of Victoria started to establish itself as the commercial centre of the Commonwealth. The bushland in and around Melbourne is basically as strong as elsewhere but, in the in-between times of the in-between seasons, it is overlaid with a misty subtlety that evokes spiritual reactions between people. Mists and a sense of poetry have always gone hand in hand; it probably accounts for the dominance of the English poets. In Melbourne it tends to produce a kind of judgment that cannot be explained by reason alone. It makes the people less pragmatic than Sydney people. The rapid changes of climate and the even rainfall throughout all seasons provide an elemental spectrum that varies from hot desert to cold sub-arctic conditions to produce an indigenous society that fluctuates between reserve and spontaneity. The elements are insistent enough to produce considered answers.

'.. their branches cast pale purple shadows on the roads that are spread with shafts of golden sunlight.'

'.. their branches cast pale purple shadows on the roads that are spread with shafts of golden sunlight.'

The original settlers lived close to the Yarra River which later became the southern boundary of Eltham. Gold was discovered and Victoria leapt overnight from an insignificant settlement of Her Gracious Majesty, Queen Victoria, into the richest colony in the world ~ a remarkable feat in the midst of that century of plunder and colonising by the major European powers.

As the gold fever subsided, the picturesque white digger characters and the Chinese fossickers in the district vanished. The few sleepy villagers that remained were connected to each other by rural activities. But most of all the quality of the district itself and the original atmosphere remained. The little hills were set at approximately half-mile spaces. The mists, rivers and creeks that produced the forests of yellow-box, stringy bark, white candlebarks and black-stemmed ironbark trees, when kangaroos, wallabies, koalas and platypi and the whole gamut of wildlife thrived, created an unbroken bushscape of alternating power and poetry.

Eltham first felt the impact of the Second World War scene in 1947.

Traditional building materials had become practically unobtainable. The black market absorbed the ex-servicemen's deferred pay and the sudden affluence of the blue collar groups were achieving a new status in the community. The pressures to build became almost insupportable with money burning holes in everyone's pockets and land in abundance. Most basic commodities were controlled and rationing was still in force.

I had run into many difficulties in the first two houses I built in Eaglemont in 1946. Being anxious to get into full time design and construction, it was natural I should think of building in mud brick in Eltham. It was the only material that seemed to be in supply, and that Shire had made no objections to this form of building. In respectable suburban Melbourne the very thought of using earth blocks or adobe as it was generally termed, would have been a bad joke. Suburban respectability was still very much the order of the day.

The Australian community had won social liberties in the 19th century such as adult franchise, votes for women, pensions and social services, earlier than anywhere else in the world. It was at tl1at time the land of the underdog, where the battler was nearly always right. Mateship and a healthy opposition to snobbery predominated. The 20th century saw the securing by most persons of a house for themselves, and the pioneering concept dwindling into the past. There was an emphasis on each man's house being his castle. An independence through possessions rather than an independence of spirit. Once land in the inner suburbs had been subdivided into twenty foot frontages for row housing, there was some justification for seeking privacy behind paling fences. As the land dimensions increased in size, the paling fence psychology created a status type isolation. As the community gained the right to quarter acre sites, the notion of the castle became progressively greater. The eastern suburbs turned into a vast garden competition with wide lawns and herbaceous borders and exotic shrubs. Hand lawnmowers moved over the tracts of smooth English grass to reduce it to putting-green quality. Every self-respecting insurance, and bank clerk house owner possessed a special weeding tool to root out the last strand of couch grass, dock and thistle, as he listened to the football on the radio. White collar. workers aspired to a new dimension denied to the artisan, who mostly rented their dwellings or lived in small iron-roofed timber cottages to the north of the Yarra. The self-imposed discipline of the garden and the bank-financed house was bringing about a new level of lower middle class bourgeoisie.

The 1920s saw a half-accepted acknowledgment of a struggle to squeeze out of community integration. A large part of the community was no longer battling as hard as it once had. Society was gradually becoming more mobile and more separated. Our neighbours could be identified more by the sound of their mowers, or the kids' tennis balls that landed in our giant lupins and petunias when they were playing backyard cricket, than as persons we talked to. Even the great depression of the 30s didn't stop this trend. People may have been hungry, but the emphasis on appearance and possessions became even stronger. We each had to be as good as the other. If we weren't, we pretended we were. If we had more than others, we half-pretended we hadn't. Superficial displays of wealth were looked on as somewhat unforgivable. We all had to look alike, think alike and live alike in this best of all possible worlds. On the surface it was an egalitarian society, but underneath it was seething with subtle stratas. They could be recognised or avoided by hiding behind the ubiquitous paling fence which protected our inner feelings even from ourselves. Our spiritual pioneering independence was being rendered powerless by the demands of an outward social uniformity as a reason for being. Underneath it all we preened ourselves if we were better off financially than our neighbour.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >