Living in the Environment, Timber Buildings

Timber Buildings

Author: Alistair Knox

Timber building in Australia has generally been looked on as the poor man's alternative to other forms of construction. The old clap board houses of the 19th century were often embellished at the corners with double thicknessed timbers to simulate masonry quoins in order to be regarded as stone construction. They were much better when they were frank, unpretentious timber. They had a quality which they have retained to this day.

John Perceval, the artist, who can now afford any house, still lives in a 19th century white weatherboard verandahed cottage at Camberwell. There is lace work round it and a Georgian ,dimensioned roof, fixtures and windows. This sort of house doesn't date because it is in timber. It has more real style than the gargantuan brick piles which surround it. I have altered this building internally in innumerable ways so that it bears little resemblance to the original plan of the living habits of its first owner. In addition we have built a pottery and painting store which is recollective of Perceval's late 1940s paintings. The brick floors are strewn with straw and there are 'angels' in the loft, just as he painted in his happy Brueghel period. Outside it has simple confidence and modest content that it would be hard to achieve with any other suburban material.

In the historic past there has always been a strong timber vernacular in this country. In the Eltham district there was a famous set of barns on 'Moray' on Bell's hill which is the first settlement in the Kangaroo Ground section of the shire. They were built by an old German carpenter in the early 1850's. Each slab was hewn from the local box and stringy bark trees and were about two or three inches thick and some ten to fourteen inches wide. The roof was of wood shingles with sapling rafters. It was destroyed in the fierce 1969 bush fire. It is hard to realise we are so close in time to those primitive manual methods. It is difficult to assess just how much the technological age has destroyed that quality and belief in work.

Great vernacular timber outbuildings, such as stables and shearing sheds, are still standing across the length and breadth of the land. Much of this was genuine environmental building. Originally clearing was a necessity to get a foothold in the primal landscape. The great tradition of anonymous timber building design is strongly expressed in Roberts' shearing shed paintings and the work of other impressionist artists. When farmers and other practical men built in local material, they built with great belief. A number of these instinctive structures took on the character of the surrounding landscape. They were mostly post and slab and roofed with sheets of stringybark, split wood shingles or corrugated iron. The straight, tall eucalypt is a unique building support, because it

is natural hardwood and very strong. It is not soft pine like the European and American traditions of the past two centuries. Any environmental planner must be passionately concerned with timber as a building medium, because of its indigenous spirit and also the fact that it is so flexible to use. Large, heavy posts formed from tree trunks, are i1'1 themselves probably the most fireproof material there is. They can also support collosal weights, vertically or horizontally. Interlocking joints can turn them into treelike structures with vertical supports and horizontal cantilevers that make it simple to contrive structural power as in the Serle house referred to in chapter 10. One way in which timber was used with great architectural character was in the solid and vertical slab construction in the Moray barn. Interstices were simply muddied up to exclude daylight and weather.

I have constructed several such buildings using second-hand mill sawn timber of three and four inch thickness. New timber is too unreliable for this purpose and re-using timber was good in itself. The joints had been sealed in a variety of ways and sometimes need attention until the old timber settles down again. It is interesting to note just how much solid timber can move when it is rehandled, especially if the outer skin is sliced from its faces. Where timber is used vertically, it both supports the roof and constructs the walls. Where it is laid horizontally, the traditional method I have followed is to erect posts at modular intervals and fix two inch by two inch vertical strips to them to leave slots of the correct dimension to hold the horizontal timber panels. The work is sealed by muddying up between each horizontal member. Such a method is generally restricted to barns and outbuildings. We have used the more sophisticated approach of setting up verticals one to the other in quite elaborate domestic structures. Today there are proprietary lines which provide good seals between vertical timber walls.

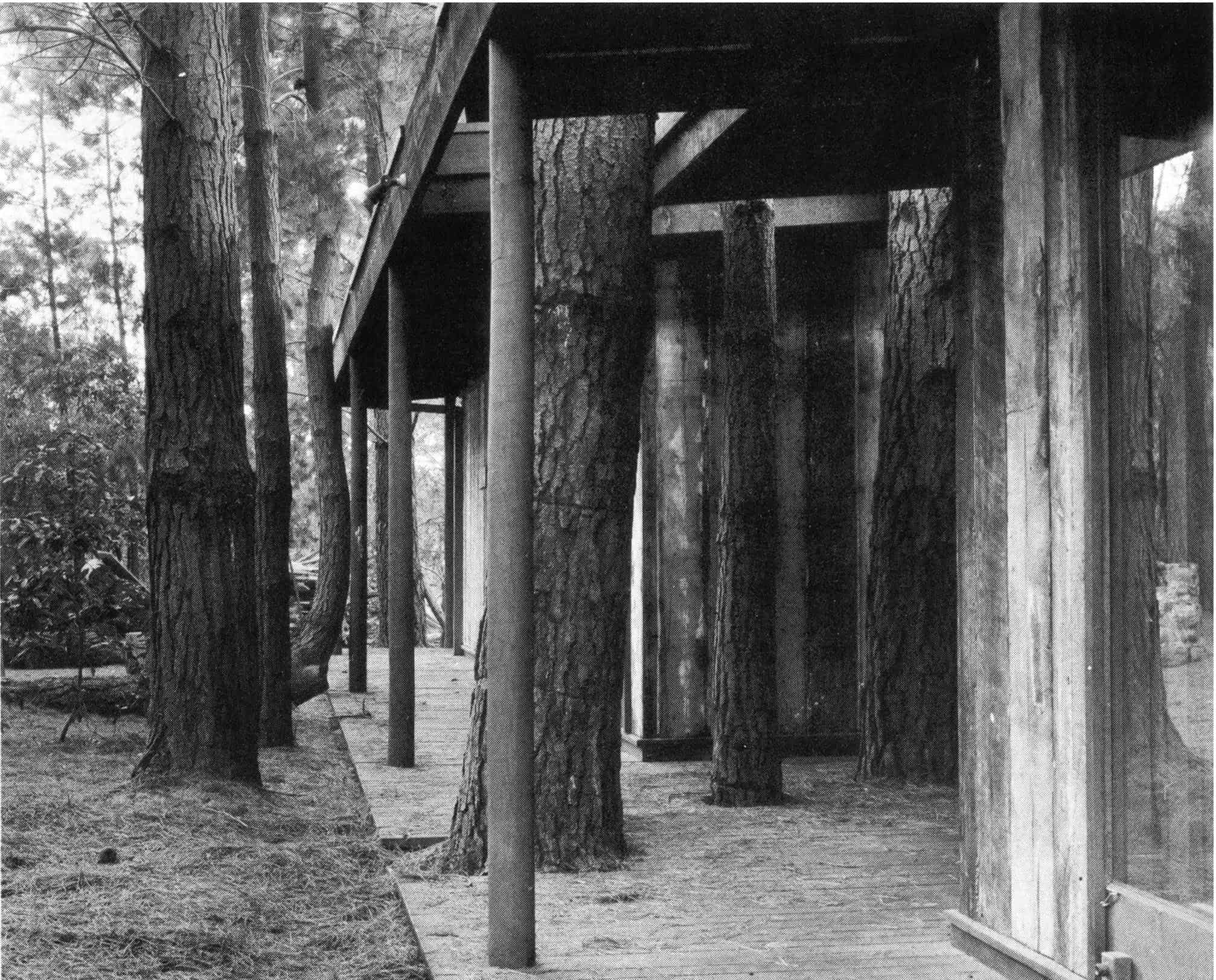

The Marks' house at Mt. Martha is a good example of solid timber building. The clients had been planning to use the land for some years. They were always frustrated by costs involved in any plans that would keep the major trees on their half acre allotment. I devised a satisfactory plan with an open layout. It had a system of sliding doors and the whole fitted into the existing tree growth very nicely. Some of the trees came through the verandah floors and ceilings. The verandah was about 12 inches above ground level. It was a beach house and these suspended platforms were vaguely recollective of a river boat. The sapling verandah posts look and feel like stauncheons. The whole of the staining is water staining, which with the mud brick fireplace, creates a strange sense of beachy holiday times - the reason for the building. At the moment there is a similar project underway on a substantial country property. Part of the original bluestone building is being retained and restored and a solid timber vernacular wing added. I secured the timber from the floor bearers of a large cool store in an area near Melbourne which has changed from an orchard district into a young executive housing suburb. It was possible to purchase over one mile of this seven inch by four inch hardwood for the purpose. That's a lot of timber to get at one time when it is Australian hardwood of even character and dimension. It the end the wreckers sold some of it twice and we had to spend a fair amount of time finding substitute material of the same size.

Whether material follows design, or design material, is sometimes a moot point. There is always a latent idea. Then you see the material. Sometimes the material fires the imagination by becoming an idea in its own right. Looking about for interesting material can be frustrating or exciting, according to your determination. I think it is a bit of an instinct.

One of the most satisfying experiences I enjoyed in timber building was with the the Diskins. There was a sense of inevitability about both the clients and the building which in many ways it had been hard to forecast.

Jim Marks house, Mount Martha

Jim Marks house, Mount Martha

I met Aviva Diskin while she was doing interior design at the R.M.I.T. when a group of students came to Eltham to view some of our recent buildings. She was serene in nature, beautiful in appearance, and of Polish extraction. Her husband, Bernie, had been born in the Bronx. He was a chiropractor with a great business based on his healing hands and his enthusiastic nature. They were a well balanced team. It seemed to me however that their outgoing natures would, in the end, be always overcome by their stylised living habits.

The first work we did for them was the restoration of a large house on the corner of St Kilda Road and Queens Road near Melbourne. It has now been demolished for the road widening programme at that corner. Around the turn of the century it had been the establishment of the favourite of the current Governor General of Australia, which no doubt was much to the horror and disgust of the respectable Victorian community.

There was an unctuous marble fireplace in the enormous bedroom where His Lordship's informal activities must have been centred. They were a part of the extensions he had made to the building. There were also a number of small rooms in the rear which were obviously for Inferior beings like cooks, servants and coachmen. I gathered a good understanding of the morality of that period when I climbed on to the roof to inspect the slates for waterproofness. It was possible to see the two standards that must have existed underneath the roof at that time. To the front the roof was orderly and well laid out, but the rear section did its job in the quickest, cheapest and ugliest way. Every consideration for the gracious favourite but precious little for her servant who helped make it possible for her to be so gracious. Thinking it over I suppose it's not much different today. Society's moral values may have changed but it's still a case of more being given to the rich and the poor losing more of the little they have.

We did our best to restore the depressed rear of the establishment into a spacious building and turn the elegant reception rooms into a warren of treatment cubicles for the thriving chiropractic centre. The patients surged through it seeking the healing touch of Bernie Diskin and his brother. There was a free tea service, piped music in the waiting room, and a great chart on the wall, encouraging all to see how the search for good health would be rewarded by a more persevering and intimate understanding of one's backbone.

It was shortly after this restoration that I had decided to look for land in order to start re-building myself. My building partner was one of Bernie's patients. It was from him that Bernie found out about the new land I was purchasing. I had not decided what to do with the piece I had to re-sell but friends had got wind of it and were jockeying for positions to buy some. Bernie rather insisted on coming out to see it the following weekend. We beat the bounds together and returned to our house. He at once pulled a wad of bank notes from his pocket and laid them on the table to seal the bargain. I thanked him as I took them and told him to phone me the next day if he thought he had taken leave of his senses. I promised to give them back to him, no questions asked. Being American he liked things sold to him rather than having to make up his own mind.

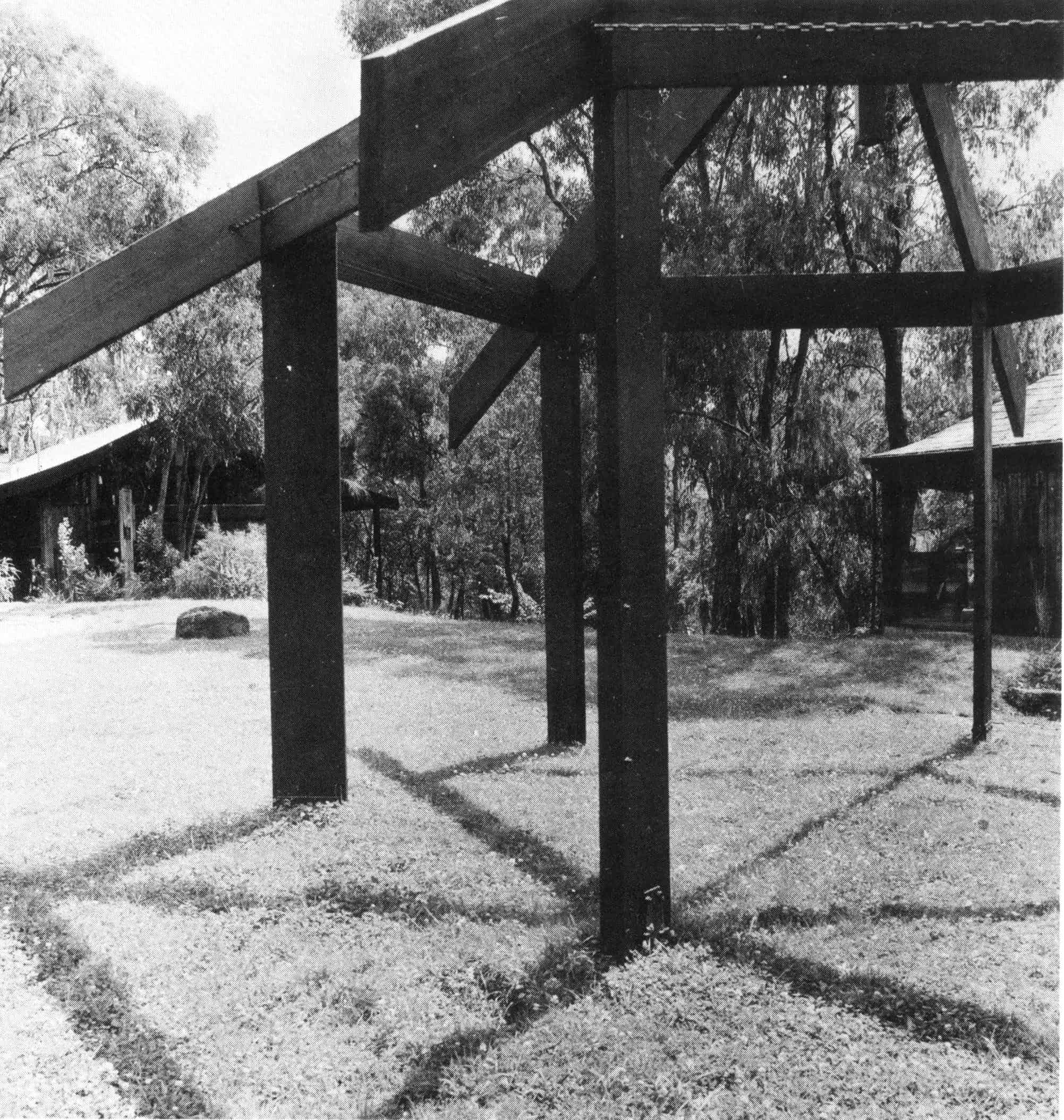

"Diskin house: converted from stable and situated amongst the candlebark trees

"Diskin house: converted from stable and situated amongst the candlebark trees

His decision to buy was confirmed the next day when one of the persons who was interested in the land came out to have another look at it. He found Bernie, Aviva and family, enjoying a picnic. I had already indicated that I thought I might cut the parcel for re-sale into two and he wanted one piece of it in preference to the other. He gauged it would be a good chance to manipulate the deal, believing that Bernie was the other possible buyer. On asking their interest, Bernie told him he had purchased the whole of it. The look of horror that appeared on his face lingered in Bernie's mind for the two long years we had to wait before the land was finally subdivided and settled.

The Diskins would visit the site at the weekend and we finally excavated for a grand stone building to be erected one day in the future. In the meantime their son had become interested in horses so it was decided to build a stable with a loft overhead in which he could spend his weekends. It was certainly an elegant stable based on a twelve foot grid pattern which was to form the corners of loose boxes for up to six horses. The posts were marvellous ten inch by ten inch jarrah recently reclaimed from the old St. James' building in Melbourne. They were twenty feet in length. A secondary site was selected for the stables situated in a beautiful clump of candlebarks on the lower side of the drive that would lead to the proposed residence. We just drilled holes on the stable site and tipped the posts into them from the back of a truck. We then pushed "them upright and set them in concrete. It was the same principle used later in the Serle house at St. Andrews. Living quarters were proposed on the upper or loft level. One day as these activities were underway there was an accident with a horse of the kind which makes people realise that animal husbandry is a serious business. This put an end to the stable idea so the plans were changed to make it into a weekend house. The external walls were in six inch by one inch hardwood with two inch by one inch cover battens laid over them vertically. They were fixed to rails and laid in panels in between the great posts and left to weather. No stain has ever been applied to them. The change to a weekend house caused us to line these planks inside with solid timber so that the whole character became something of the vernacular of the early Australian timber buildings, both inside and out. The roof was of curved iron which visually emphasised the sweeping character of the surrounding landscape.

Diskin house; from the gazebo with Aviva's wing on the right

Diskin house; from the gazebo with Aviva's wing on the right

The verandahs were nearly two storeys high and the verandah posts gave the building its own indigenous Eltham spirit. Incidentally this high verandah had remarkable temperature controlling properties at the same time. At the gable ends it was possible to walk out on ground level under the shelter of open platforms that were entered from the first floor. The ceilings were lined with water stained lining boards from a demolished stable direct from the suburbs of old Melbourne. It was like a two-layered tent. A staircase penetrated the upper floor from the centre of the building. Both upper and lower levels were unsubdivided except for the provision of a bathroom. Brick paving was laid on a ground level and simple flooring over the heavy beams in the loft above.

The Diskins felt themselves drawn more and more to this simple bush landscape building. When the road widening threatened their city home, they decided to try living in it permanently. They had three children which were soon to become four and no bedroom either for themselves or the children. What did I think they could do about it? There was an enormous fireplace on the ground floor, the opening of which was about nine feet by six feet high. With your back to the ironbark logs that they had burnt in it throughout the winter, you had a direct view of the upper floor through the stairwell. It only required two or three good Persian rugs hanging down from the timber ceiling to somewhat obscure that opening and create a building of mystery with a semi-eastern or semetic character. Both Aviva and Bernie claimed they were Jewish but the only religion they seemed to practise at that time was the eating of special cakes and food on Jewish holidays. But Aviva had something of the dusky Persian princess about her and Bernie could look like a young Jewish prophet when he went on a dieting binge and grew a black beard.

Diskin house: Persian rugs sub-divide upstairs areas

Diskin house: Persian rugs sub-divide upstairs areas

The house took them over. They entered into a new life, a new life role and a new life style. The children had bunks built into the sides of the upstairs room. They were neat, inspiring couches after the style of those in the little ship I had sailed in in the navy. I decided to add another bay twelve feet deep by the width of the building to the rear end of the house to provide a gracious bedroom and bathroom away from the hurly burly of the children. Coming from a twenty roomed house, this seemed the least that could be done. We left the existing external glass walls upstairs when we extended the building so that you could see into the bedroom and indeed straight through the house like a tent. Though glass, the walls would still dampen down the noise. The Diskins however always kept the parental bed in the' main part of the upstairs room and hardly used the special bedroom area at all, except for its spatial qualities. They had become a family that enjoyed sleeping and living close together again. There never seemed to be a great row or confusion going on either. I felt confident that it was because they were not heriuned in. There was nothing to rebel about; no small special rooms for special children. It was just simple and natural and they responded just as naturally.

The living style suited them enormously. Aviva even had the washing machine installed outside so that she could spend more time in the open air. The transformation that took place in their thinking and doing was exciting. Health foods and home grown vegetables alternated with fasts and dieting and the accent was on the simple quality of experience in the here and the now.

Aviva was a builder by nature. After a couple of years in Eltham she told me that they had retained some of the great beams I had erected as a pergola over a car park in their St Kilda house and chiropractic centre. She thought they should be made into a gazebo which in due course they were. The trouble was that there were still some beams left over after this, and she did so want to build a little gazebo shaped house on two levels for the girls - one level to sleep in and one to entertain in.

Diskin house: Aviva's wing interior

Diskin house: Aviva's wing interior

I often called in to the Diskins' at about nine o'clock in the morning after dropping all our children at the local school. They would be drinking coffee and eating delectable cold fish dishes and other elegant health foods. We would discuss the plans for the building because it had been determined that this should be Aviva's house, subject only to a kind of priestly incantation that I would perform over it from time to time. I was to supply carpenters and other tradesmen and Aviva was to enjoy the expensive experience and the expensive privilege of changing her mind from day to day as the building progressed and the ideas formulated. Although it proved a costly addition in terms of money for the bricks, timber, glass and slate, it was cheap indeed in terms of gaining the depth of living and doing experiences that Aviva gained.

The Diskins became interested in religion and were asking about the things in the Bible. Coming from a good Calvanist background with some knowledge of the Old Testament scriptures, I would expound for hours on the certainty that the Old Testament messianic prophecies were fulfilled in the Jesus of the New Testament. I myself had been converted to Christianity at the age of forty, or had at least become aware that a childhood acceptance and an adult commitment were two different things. It had caused a revolution in my own life. Prior to this time I had regarded many clients as necessary evils. I would get annoyed with their precious and unnecessary requirements. They seemed to stand between me and my great ideas.

The first sign that I was not the same person as I had been before this spiritual encounter with Jesus was that although I did not like my clients any more, I found I couldn't help going out to them and becoming involved in their personalities and their requirements. The result was that as I listened, I learned. The designs took on a depth and a variety of interest as each became a personal extension of basic principle. I discovered that the person is the most important clement in the environment. Each one reflects it in different ways and adds to the spirit and dynamic of it indefinitely. On reflection it would appear that much of the magic and. inspiration we find in older cities and habitations of man is due to the care the succeeding generations graft into it almost unconsciously.

True architectural design requires a perception that exploits the best in all times and materials by welding them into a unity with eternal longings in them. A person who has no conviction of a hereafter can only design for today or for the dead. One who believes his citizenship is in heaven believes that what he does for today is for all time. This is one of the reasons we build so few monumental buildings today. They imply unchanging convictions, which is so far removed from the present concept of mobility that requires everything to be changed in a decade or two to another fashion or another idea. How can people hope for eternal cities and habitations in this state of mind?

Bernie had to make the trip to St Kilda every day. It was a good distance from Eltham. At one stage he suggested a return to South Yarra for the week days. The remainder of the family wished him well and said they would be happy to see him any time he came to Eltham but as for them, they would never move back to the city. They had become Eltham fixtures.

Some time later Aviva decided to visit Israel. She phoned Bernie about the second night after her arrival and told him that she wanted to buy a house in Jerusalem. The building had not yet been started but plans were prepared. If it had been half up I think she would have stayed on without ever returning to Australia again. As it was, she finalised the house purchase and came back to set her affairs in order and make preparations for a permanent departure for the spiritual home of the Hebrews. I asked her if she really knew why she was going. She could only indicate that she felt it was like an inner command to go. If ever I saw the Old Testament statement that God would call his people home from the countries into which he had sent them, it was here. When I said this Aviva agreed wholeheartedly. The sense of a community and identity is as strong as Jewry itself.

Just after the Diskins decided to leave, the man who had wanted to buy their land when they came to Eltham, suddenly appeared again. The Diskin house, like many buildings we do, was sold by word of mouth. Someone hears about it and that's it. In the meantime he also had one of our buildings and someone had heard about that too. It was sold by word of mouth as he moved in to buy the Diskins. He was a cautious operator and Bernie got a bit impatient about his deliberation and told me he would sell it to anyone else who came along. I advised him that in my opinion he was wasting his time thinking anyone else would come. Everything to do with that house had a sense of inevitability. Come what may, his old sparring partner would get it, and of course he did. It is now weaving the same quality of timelessness over him and his lovely wife. She had said that she didn't care where she lived but a couple of weeks in Eltham has changed all that. Now she never wants to leave again.

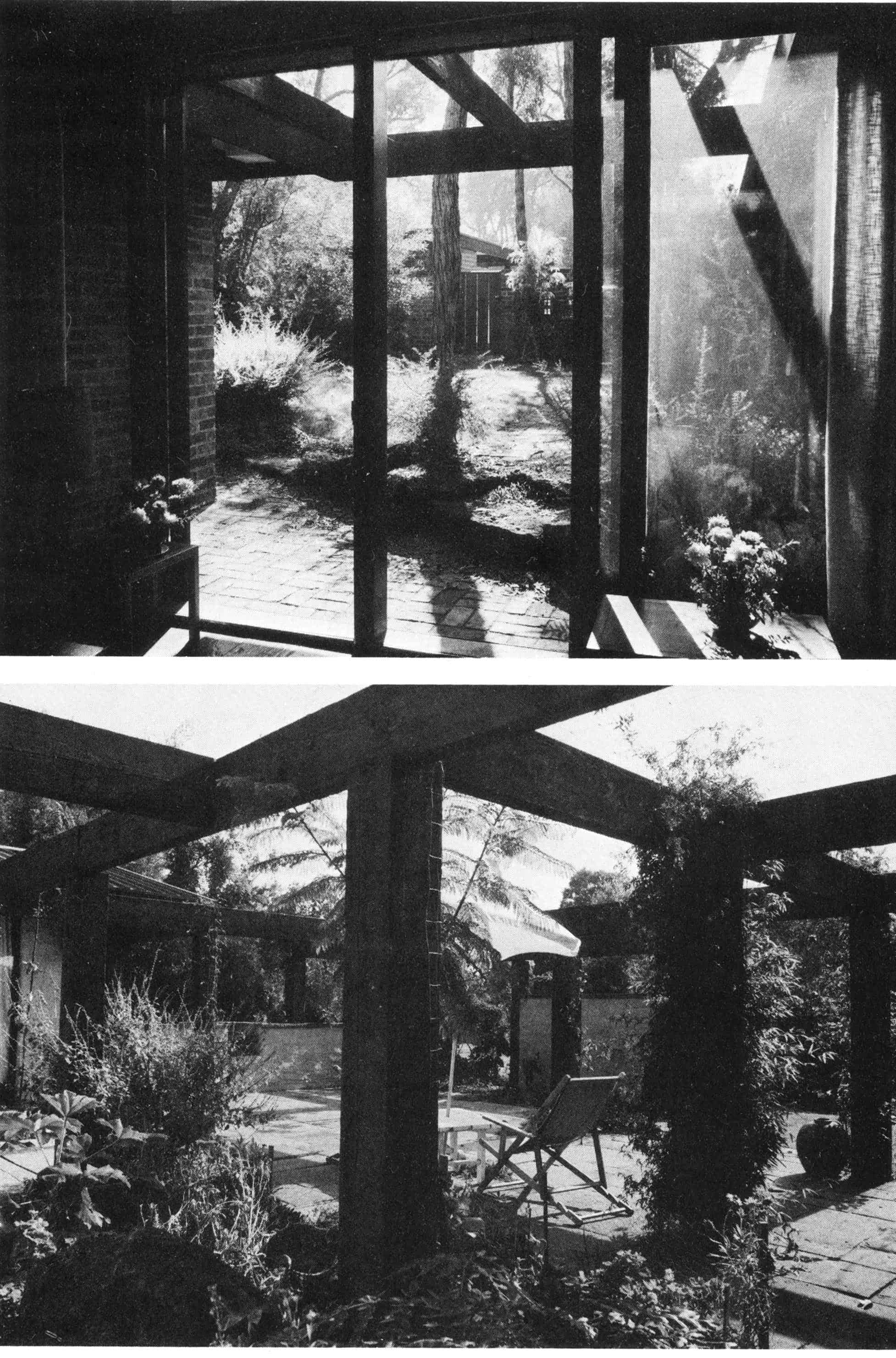

Examples of suburban house and landscape planning. Above top: Fagan house Mount Waverley.

Above bottom: Courtyard, Cooke house, Camberwell

Examples of suburban house and landscape planning. Above top: Fagan house Mount Waverley.

Above bottom: Courtyard, Cooke house, Camberwell

A young married couple named Wain called on me in 1974. They wanted to get an acre of land in the district for about half the usual amount and build a house for two-thirds the minimum price. I was able to refer them to a rather extraordinary allotment of about sixty-six feet width by about six hundred feet in length. It was bush land and rose very steeply to somewhere about the middle of its length and then dropped just as steeply away to the other side. In some ways it was almost an impossible site, even to get into, but they were inventive and optimistic.

The building I designed was planned to rise some twenty feet in height and to straddle the highest part of the land. A curved and sweeping iron roof with clerestories and changes of level made it into a piece of sculpture. It was formed from electric light poles and had the same mud brick influence as John Serle's.

Jill Wain turned out to be a superb organiser. She automatically understood the wrecking jargon to obtain those special materials which make such a building possible. For instance they obtained large squared slate (which is now almost unprocurable) by buying the Saturday papers that came off the press at midnight on Friday, and finding an advertisement 'Slate for Sale' at Kilmore fifty miles away in the country. They set off on the track just after daylight and found the man who was wrecking the primary school drinking in a local pub at an early hour. They purchased the slate, loaded it, and were back home by lunch time. This is the spirit that underlies the environmental 'do it yourself' building scene.

At a more expensive level, Lawton Cooke, the managing director of a large company, and his wife, commissioned me to design a building on expensive suburban land in a most salubrious area of Melbourne. I found out that it was still designated as a timber area; that is it was a zone in which timber houses could be erected: When we discussed planning it emerged that Lynn's instinctive ideas were in the mud brick vernacular. I immediately suggested we use mud brick and timber construction. Practically all the more elaborate areas of Melbourne are zoned for brickwork only, which means that the external sheathing of the building must be in machine made baked brick. Timber is not considered classy enough, although no one raises the slightest objection if the building is timber framed and merely pmvided with a brick veneer. Our Mrs. Everige society is much less interested in what goes on underneath as long as it looks expensive on top. This land had not been zoned a brick area because it had been fully developed and established so many years earlier. The Cookes" acre became available because the original house on the land had been demolished.

Camberwell is a cautious district, full of prim business men. The civic fathers make every endeavour to see that second hand bricks - no matter how beautiful - shall not be used in the external walls. It is apparently not conforming enough in the climate of the mundane middle class. In 1912 Lawton Cooke's grandfather bought a building in the city of Melbourne that had been built during the late 19th century. It was being demolished as we planned the house. At the risk of our lives we clambered over its gutted interiors and negotiated to purchase the whole system of floors and supports of great oregon timbers of twelve by twelve inches and thicker.

We then designed and constructed a series of simple, but elegant metal brackets to bolt into all the vertical and horizontal members these provided, to create a timber skeleton. It was similar to a steel-framed building. The in-fills were to be of glass and mud. It seemed a formidable task to offer such an outlandish proposal to the building authorities for their approval. I prepared some computations to show that it could stand up, sought an appointment with the building surveyor, asked Lawton Cooke to walk a few paces in the rear, making managing directors' noises, while I eulogised the plan and the use of mud. We then invited the building surveyor to examine similar structures such as our own, the Hastie's and the Barden's across the river in Eltham, to see that what we proposed would not fall down or melt in the first storm. He graciously obliged and was duly impressed. We crush-tested some bricks for him and the council quietly issued a permit. I heard subsequently that the specification for making bricks, which included such medieval facts as adding one whisk of straw to a barrow load of earth, caused some flutterings in the council chamber. A whisk, incidentally, means a handful.

The result was good. In fact it was so good, that within a year or two, Lawton was considering resigning his managership of that million dollar business and become a 'Murray Grey' farmer on the Mornington Peninsula. Such is the power of environmental building over willing subjects, even in the suburbs. It can change our whole way of looking at life. I've already made preliminary plans for an exciting new project for the Cookes, while he is busy sculpting the landscape into dams and mysterious masses and voids in the best 'Capability Brown' tradition. It is one of the best holdings in the whole peninsula, in some ways strikingly similar to parts of the high country at Cobungra on the slopes of Mt Hotham. The open spaces are sub-divided by dense lines of melaleucas marking the creeks that wind through it. These are all being fenced and preserved, just as Cobungra in most places is subdivided by the strong natural features. Even a group of great pine trees, which are generally anathema to me, seem to fit into this landscape with its views of Westernport and Phillip Island in the distance. The building will again be framed from heavy timbers, this time twelve by six inch red gum bridge timber and in-filled with mud. It is perfectly true that once you have lived in a good earth building, you will never live serenely in any other form of construction.

The Wains' house was the catalyst for a whole series of do it yourself buildings in the Eltham district. We design the buildings and supervise them. The owners organise the finance, pay the sub-contractors and fossick out interesting reclaimed material. At the same time they become identified with the district. All the men purchase adzes and set out to clean up redgum posts from our special store. Most of the clients are professional types such as accountants and other erstwhile members of the corporate state system.

It is fascinating to watch the metamorphic change as the grubs turn into butterflies, sipping spiritual nectar from the bushland scene to grow strong in the character of the pioneer. A new reverence is engendered in the humble electric light pole, the adobe block, the bluestone pitcher, heavy second hand timbers and the whole gamut of environmental building materials that are producing an alternative society second to none. I believe we are involved in a movement that could become a major factor in winning the environmental battle for survival.

As the natural environment is a vertical matter so is the building scene. There is a deep reverence among do it yourself builders for an adzed post twenty feet in length standing vertically in the middle of the building site. The house and the land have become one and they are also at one with it. A spatial relationship is restored between man and nature. The mind and body of the corporate state man are transformed into the spirit, mind and body of the environmental man who finds 'Tongues in the running brooks, sermons in stones and good in everything'.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >