We Are What We Stand On, The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

Author: Alistair Knox

It was because I was older than most of the Eltham community that I had a slight glimmer of the meaning of the indigenous environment before they did.

My real understanding, however, began in 1948 at the beginning of my association with my present wife, Margot. She had attended RMIT art school and although she had not worked as strenously as she might have, the paintings which she did and the work she produced gave evidence of a natural talent that has been developing ever since.

It was appropriate that we should meet at Matcham and Myra Skipper's studio behind the Russell Street Police Station. It was the most popular artists' rendezvous in Melbourne during that period. During the same year she rented a bungalow in Ivanhoe from a Mrs. Morris who introduced her to Ellis Stones, the landscape gardener.

Ellis Stones was also called 'Rocky' Stones by those who knew and appreciated him. He, together with Edna Walling, another landscaper, were the genesis of the real Australian landscape tradition. They had at one time worked together and in a variety of ways influenced each other.

Edna Walling was rather earlier than Stones because he was still emerging as a personality after the War when she had already established her reputation. Her designing was comprehensive in concept but English in character. Ellis Stones, who did not die until the 70s was much more endemic, but not wholly so, either in planning or concept.

He reached the pinnacle of his career on the day of his death at the age of 79. His last project was in Rosanna. The Board of Works agreed to landscape the Salt Creek in the Elliston Development instead of barrel draining it as they had intended. David Yencken and his firm, Merchant Builders, together with Ellis Stones, who developed this excellent residential development, gave him his greatest opportunity to demonstrate his creative genius with great boulders and natural land shapes. The project was named 'Elliston' in his honour.

Both Edna Walling and Ellis Stones were a natural outcome of the post First World War period. Their gardens, together with Walter Burley Griffin's drawings of Melbourne landscapes, executed during the 20s, all contained one common element; each had been produced by a mind with a resolved philosophy. Each expressed ideas which separated them from the attitude of the Brunning's and Railton's gardening manuals, which were the garden encyclopaedias of the time.

Guilfoyle, the main landscape architect for the Royal Melbourne Botanical Gardens (which are acknowledged as one of the best 10 gardens of the world) was the only real inspiration available to Melbourne people. They could hardly be blamed for trying to transform their suburban blocks into minute imitations of his preponderately exotic plantings.

The people of suburbia, prior to the Australian landscaping movement, were guided in their garden plans by nurserymen who concentrated on horticultural gardens featuring asphalt or concrete drives, herbaceous borders, hollyhock corners with torulosa and lambertiana hedges rising darkly green behind them.

Flower beds of azaleas, rhododendrons and other Himalayan exotica, surrounded by edgings of lavender and forget-me-not occupied the centre of lawns. These were complemented with cannas, snapdragons and giant petunias to provide 'colour'. Oaks and chestnuts were for bigger gardens with branches of 'triumphant' palm rustling together in the wind, accompanied by the raucous Indian mynahs squabbling in the midst of the half-ripened dates. Only a rare eucalyptus was allowed to flourish because of their continual shedding leaves and their English lawn-destroying habits.

Burley Griffin got rid of many of his American planting attitudes in Canberra when he lived at Heidelberg in the early 20s and fell in love with the Australian landscape. His tiny house looked out over the Plenty Ranges towards Eltham. His plan took on an Australian spirit but his developed Melbourne landscapes were few and far between.

Fred Aldridge, the Sun Newspaper executive, who died about 20 years ago, lived next to Burley Griffin in Glenard Drive, Eaglemont. He knew his movements very well. He was not very complimentary about him. He said he was a bloody fool who spent a long time growing trees in pots and forgetting to water them so that they all died. This was a very narrow view of his extraordinary potential.

My own belief is that the Australian landscape was making its presence felt on him at this period with great power that would colour all his subsequent work. There is good evidence for his opinion when one thinks of his later total planning at Castlecrag in Sydney. His ideal of planting two or three trees in one planting hole describes his meditation of the Australian flora and its effect on him.

It was shortly before my wife, Margot, came to live in Eltham that she started working for Ellis Stones, who was then becoming known as a landscape designer in his own right. He was at this stage still very cautious about employing labour because his profession was a very tenuous one. The term 'landscape gardener' and 'maintenance gardener' were, in most people's minds, interchangeable terms. The chances of being paid for landscape advice were slender because most clients believed that every Englishman's house was his castle. They were persuaded that no one could design their gardens better than they themselves, and at this time public landscaping was the preserve of curators and greenkeepers.

In his early days, Rocky Stones tended to employ girls rather than men because they cost less, were easier to hire part-time, were uncomplaining and often superior at the work. This was why he asked Margot to do some slate paving for him. She turned out to be excellent at it. It was an enormous area of a property known as Mount Pleasant, which at that time was owned by Bill and Patsy Harrison. I had recommended 'Rocky' Stones to them to develop their landscape.

Margot was not yet 18 years old. She would often leave home with a very meagre lunch. It was a very cold time of the year. By 10 o'clock she would be starving and freezing on that high, exposed site that commanded views of the mountains on one side and the sea on the other, pining for a cup of tea. The Harrisons were generous to a fault. They often drank French Champagne and other exotic drinks at about 10.30 a.m., but they did not understand how a worker appreciated a tea-break. Instead, they would send out bubbling 'champers' in a cut crystal glass to show their appreciation and to speed her on her way.

Ellis Stones became ill at this time and I had to organize the work in his absence. Margot, he and I became great friends. He was a shy poetic man and became recognized largely as an Eltham person in the 50s. I was the first to introduce him to Robin Boyd and the other architects, which was the beginning of a new relationship that would spring up between architect and landscape designer in Australia.

A little later, I suggested he should employ Gordon Ford, and a strong mutual attraction was to spring up between them. In the meantime, Margot finished her paving at Harrison's and for a period became the best pavior of random slate in the business. She was an artist to her fingertips and Rocky taught her the elements of true paving that was to stimulate a demand for her work amongst discerning clients. She also did some beautiful pavidg on some of our buildings.

Margot still occasionally worked for Ellis Stones when he employed Gordon Ford, who was one of the funniest men of the district. They all laughed so much as they worked together that the next door neighbours would put their heads over the fence to ask them what it was th~y were laughing at. 'Rocky's' depression stories and Gordon's memory and quick tongue made the jobs the most enjoyable of all those hysterical times that made Eltham the centre of the eternal laugh between the years of 1945 and 1950.

Who could have forecast in those early carefree days that Gordon would become such an enormous influence on the natural Australian garden development that has swept the country since 1950? He had originally worked for me on mud brick buildings, but was to discover his natural talents lay in expressing aspects of the mysterious and powerful landscape of the Australian hinterland. He had an immediate, natural feeling for the work that 'Rocky' Stones introduced him to when he first employed him. He responded to the inspiration of his own childhood, which had been spent in country areas.

'Rocky' Stones came to his understanding of the Australian landscape in a similar way. When he was first asked to design a natural garden, he thought back to how it felt to him when he was a boy. He had lived in Euroa and would go out fox shooting. What he recalled was the meandering bush track along which he used to wait for them to appear. He would rest his gun on a great boulder beside the track and meditate.

The scene re-presented itself to him 25 years later when he was first commissioned to do a natural garden. The extraordinary influence of an unspoilt landscape, produces visions on the heart and mind that can never be eradicated. For this reason, it is all the more remarkable that the renaissance of the natural Australian landscape took so long to emerge.

Stranger still, even to this present time, only about half of our population has any real understanding of our indigenous bush and landscape, which is the greatest single factor that has produced our national character and personality.

It was the Englishman, D. H. Lawrence, who saw the natural qualities of the land better than almost anyone else. In his book 'Kangaroo' he made many memorable observations about it all. He called our bush 'the morning of the world' . Its genetic individuality and organic formlessness are the secret of its eternal sense of mystery. In addition to his own natural landscape yearnings, Gordon Ford arrived on the scene at precisely the right moment to make his mark.

Ernest Lord, who had identified the tree for me from Burley Griffin's garden some 10 years earlier, was at this stage conducting a landscape study group in a strange hired meeting room in the city of Melbourne.

He had become a recognized figure since the publication of his great book, Shrubs and Trees for Australian Gardens. Gordon, exhausted from working all day in the field with 'Rocky' Stones, would stagger into the city armed with a case full of specimens for identification.

He was determined to know everyone of them. Ellis Stones did not have this knowledge as nearly all his experience was instinctive. By fortuitous circumstances Gordon had worked in the Forestry Commission before the war and had a father who was a Presbyterian Minister with an excellent knowledge of Latin. He found he had inherited from him an ability to handle the Latin names of plants, so he was put in charge of all the Sales at the Forestry Commission.

Ernest Lord's precise nature had expanded a little with his reputation. I frequently met him at the Artist's Colony in the weekends because he was a good friend of Mervyn Skipper, Matcham's father, who also had a nursery of exotic plants. When Gordon would produce an obscure specimen for Lord to identify, he would draw in his breath and say 'Ooh, that wrenched my mind'. But that was only a shadow of the wrench he experienced when Gordon produced a specimen he had failed to record in his book. It took him some time to recover. It was Ellis Stones' lack of academic training that give him such freedom in his design.

Ernest Lord knew the plants and their names, but Ellis could visualize the worn-down hills, the ancient boulders and the 'the morning of the world' plant life he remembered from his boyhood, and could then put his thoughts into action.

There was a considerable intermingling of landscape and native plant personalities around Eltham in 1950. Schubert, the native plant man, was growing a great number of fascinating new shrubs and trees in his nursery at Noble Park and many of these products found their way back to Eltham gardens. Gordon recalls how he saw his native bush floor and caught a new vision about doing away with lawns. This was emotionally reinforced by a visit to the Mallee, where he discovered that the whole landscape was one enormous garden that could not be changed.

The most famous Australian plant farm of the early 1950s was the Eastern Park Nursery at Geelong, owned by E. N. Boddy. Boddy was connected with E1tham through Ivo Hammet and at the present time through his daughter Janet, the romantic painter. Janet told me her father, before his death, had written a book yet to be published called 'Australia Replanted'. It's a title which stimulated the mind with its inferred scope and dimension.

Dorian Le Gallienne, the composer, who was one of the most discerning men Eltham ever had, probably understood more about the intrinsic spirit of the natural landscape-its orchids, its teeming variety of amazing phenomena-than anyone else. Alan Marshall remarked recently how some of Dorian's awareness of the bush had infiltrated into his musical compositions.

When we were building the second wing onto the Downing/Le Gallienne house after Dick Downing had returned from Geneva in 1954 we would all sit round on the terrace for prolonged morning teas, observing virgin nature and the birds. The painter, Clifton Pugh, who made the bricks for this wing, also built the earth walls for me. The Sibbel brothers whom I also employed at that time, did the carpentry. Several other interesting personalities made quite a memorable building group. As the structure neared completion, Gordon Ford was called in to complete the landscape which Ellis had commenced on the first wing.

Gordon by now was firmly established in his own right and he was rapidly creating a demand for his native rocks and log landscapes. Ellis Stones was asked to do the boulder steps and some other parts of the work, but he was very crippled at that time, from the effects of a severe leg wound he received on the first day of the Anzac landing at Gallipoli so long ago, that he could not walk.

I coerced him onto the site and placed him in an armchair and told him to direct Gordon and another to place the boulders according to his directions. He used to call the heavy work of placing boulders 'the caveman's annual sports day' and with a series of well-known jokes encouraged them on. When they got one in position, after considerable grunting and bending of crowbars, he could restrain himself no longer. 'That's it', he would shout and leap up and hop on one leg over to the scene and start ramming earth around the boulder with his crutches.

The significant landscape names and influences running through the Eltham society at the time were like the various streams of a delta that flowed in and out of each other. They were all fed by the one great stream of the indigenous Australian landscape that surged down from the plains and the mountains of the untamed landscape beyond the district.

Many other names spring instantly to mind, such as Miss Wardell, whom I never had the pleasure of meeting. Some of the descriptions I have heard of her show her to be a very strong personality with a passion for the untouched bushscape that transcended all others we knew of. She was able to persuade 60 shires and cities to fence in small pockets of land and declare them native plant sanctuaries. Nothing was done to them at all, except to leave them alone. They were just allowed to regenerate. She was a great protagonist for the 'morning of the world' theory. She was an early environmental activist, and a purist in the keenest sense of the word. Dorian Le Gallienne had invited her out to his and Dick Downing's joint property at Yarrabraes Road but on the day she was seen approaching the house with her long walking staff preceding her only Dick was at home; Dorian had been called unexpectedly to the city. Dick had a good appreciation of native plants but he was much more catholic in his tastes than Miss Wardell. He conducted her around the property and when they unexpectedly came across a group of three Cootamundra wattles Dick employed all his well known charm and urbanity as he remarked how beautiful they looked with their bright golden blossom. Miss Wardell's reply was most uncompromising. She started hitting at them with her staff. 'No they don't', she said between her teeth, 'the bloody foreigners!' It was too much for Dick, who left her to deal with the landscape as she chose. He retired to the kitchen to bake a cake and wait for Dorian to return.

One minor humorous incident affecting the Downing/Le Gallienne landscape appeared in the form of a young matron who arrived on the land next door. She had just bought it and had come down to make the acquaintance of Dick and Dor. She was accompanied by a couple of young children with exotic christian names, and she herself was dressed in a pastel-coloured, light whispy dress. Dick and Dor would often catch glimpses of her tripping lightly through the bush like an English maiden out of place. She would sometimes camp beside her car on the land and pay them a visit in the mornings, dressed either in a elegant dressing gown and slippers or in a lame gown with shoes to match enthusing about the beauty of it all. She appeared determined to change the strong Australian landscape character by planting jonquil and daffodil bulbs among the greenhood and spider orchids as though they were all meant to go together.

One hot morning I was driving past the land and I noticed that she was not there, but Alan Hempel, the neighbour opposite, was beating out a small fire that had just sprung up. I asked if he was alright. As soon as I heard the tone of his voice I leapt out and joined him. We beat until our eyes were red and our lungs were bursting, and finally extinguished the blaze. Alan, leaning on his improvised beater, used the last shreds of his energy to berate the neglect of the lady with the veils who had danced off without putting out her morning blaze .... The 'neglectful lady of the veils' sold her land not long after the potentially-tragic fire she caused, to the relief of us all.

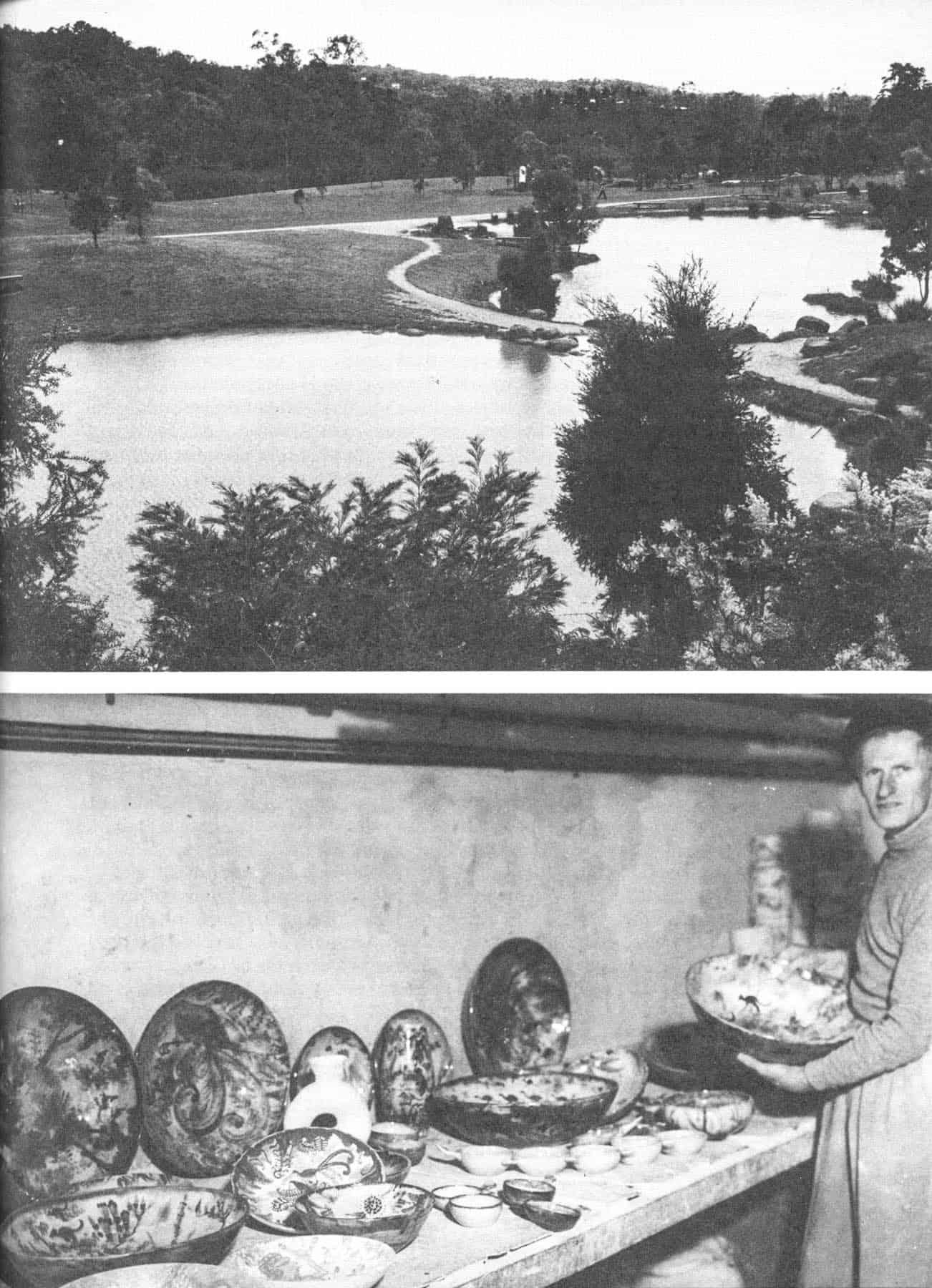

Above top: A general view of the Town Park, commenced in 1973, which was the culmination of the ideas f the landscapers who worked in Eltham from 1948 onwards.

Above bottom: Neil Douglas and his native flora and fauna decorations

Above top: A general view of the Town Park, commenced in 1973, which was the culmination of the ideas f the landscapers who worked in Eltham from 1948 onwards.

Above bottom: Neil Douglas and his native flora and fauna decorations

Neil Douglas was another Eltham identity who was concerned with the re-discovery of the natural landscape and planting although he was at this stage still developing an English-type garden at Bayswater. Neil lived at John and Sunday Reed's property at various times between 1945 and 1950. It was situated just on the Templestowe side of the Yarra River, adjacent to Banksia Street, Heidelberg. John and Sunday were the acknowledged entrepreneurs of the modern art movement which effectively started in Melbourne in about 1930. He is well known as the founder of the Contemporary Art Society.

It included such figures as Sam Atyeo and Moya Dyring, with whom I shared a studio in Little Collins Street in 1933. John Reed was the Director of the Museum of Modern Art for many years. Sid Nolan, the famous Australian painter, also lived at their house, around the same time as Neil. Other well-known artists were frequenters of the Reed menage, including all the members of the Boyd family, John Perceval, Bert Tucker and his wife Joy Hester, and a great many other well-known names.

Nolan painted his original Kelly series at the Templestowe house. I recollect calling in one morning and seeing him looking at about six line sketches of a masked face with the intention of selecting one for one of the paintings. They lay on the floor around him and a paperback history of the Kelly Gang lay on the floor beside him.

His rise to his present elevated position was a gradual reality and not a meteoric stardom. He is a poet as well as a painter and his philosophy had been a gradual accretion, like the growing of the pearl rather than the sudden bursting of a star.

The Reeds were obviously the high water level of discussion in the current art world when Neil first stayed there and he was the only person among the more important members who had any intimate knowledge of the Australian bush. Arthur Boyd and John Perceval were in the midst of their Bruegel period and although Sid Nolan had painted his Dimboola series, and regarded them as Australian, Neil nettled him by calling them a series of trains traversing wheat fields that could have been just as valid in North America as in Australia.

These comments came directly from Neil himself and I do not wish to take sides in the actual discussion. Distance does lend enchantment to the recollections and it is possible that statements made so long ago may have become twisted out of perspective. Neil Douglas eventually agreed to show Sid Nolan, whose work he had criticized for lacking an Australian 'feel', some fern gullies and Mt. Dandenong wilderness in the Heathmont area.

Neil claimed that shortly after this excursion Nolan came out to his studio in great excitement with his blue eyes shining and his irises penetrating like gimlets, shouting: 'You are right, Neil. It's like the morning of the world'.

Neil never knew if he understood he was quoting D. H. Lawrence or if the thoughts were new to him, but he said that the painting he had just executed was later handed around the artists as they started to comprehend the inner meaning of what the natural environment really was.

Neil argued that McCubbin, the great early Australian Impressionist, and many of his contemporaries lost the real quality of the bush because they ordered it. They did not understand its formlessness or the spontaneous local condition and variety it expressed.

There was no doubt about the effect that Neil began to have on the decorations at the Arthur Merrick Boyd Potteries, where he worked with Arthur Boyd and John Perceval. There was criticism at first because they thought the bush he wanted to paint would be like the old Victorian engravings of the aboriginal and his habitat. When they saw his first decorations they immediately understood he was interpreting it in a different way. When I first went to the potteries, they were in the midst of an endless native flora and fauna decoration binge.

Neil did not come to live at Eltham until 1962 and it was not until after that that he started to make his presence felt in the natural environment in this district. His greatest contribution to the landscape has been in terms of the Residential Sanctuary proposals which he finally attained for the land around and beyond the Bend of Islands at the eastern tip of Eltham. It was obviously this fact, together with his original conservation prize, that caused him to be awarded an MBE by an appreciative government.

For years Neil has made a strange contrast in his hand-woven suit, wavy beard and bushy eyebrows, to those neatly attired, pepper and salt suited Liberal politicians in the Victorian Parliament, where he has always been an effective figure. I recollect Neil saying, 'I think I've pushed them over the limit and I'm worried about it'. I said 'Neil, there's no need to worry, they're much more frightened of you than you are of them'. This strange thought had never struck him, but of course it was perfectly true. He laughed for hours after he thought about it.

The general concept of the Australian landscape planners of Eltham has been heavily influenced by 'Capability' Brown, the great landscaper of 18th Century England, who changed the face of that whole country.

He was the inspiration of men like Gordon Ford, Peter Glass (who worked with both Gordon in landscape and myself in building design) I van Stranger and Bob Grant (the present curator of Eltham shire). We all emulated Capability Brown with his two and three dimensional forms to produce a whole new attitude in landscape design in this country.

Gordon said it was reading Brenda Colvan's book 'Land and Landscape' that touched off the final vision in his case. Peter Glass had some slight connection with Edna Walling before the War. The individual manner in which he placed the early trees on his hill at the top of John Street indicate an originality that one would not suspect without some such influence having taken place.

At one stage in Gordon's career, Edna Walling paid him a visit to see if he would work for her. Gordon said her arguments were cogent but he was sorry to have to tell her that he could not oblige her as he himself wanted to add his own influence. Peter Glass was absent from Australia for some years from about 1951. He did not return to work in Australia until 1958. He then designed landscapes with Gordon and architecture with me.

My office was at that time in York Street, Eltham, attached to our second house on that property. It was divided from the main building by a breezeway and a glass wall, so that everything that took place was clearly visible from the kitchen. Margot saw Peter with his chin in his hands one day, looking depressed, so she asked him, what was the matter. He said he was thinking of a girl called Cecile, whom he knew very well in France, and was wondering about her. Margot, with true feminine instinct made him write a proposal of marriage that day.

In due course, the answer came back: 'Roses, roses all the way!' She would arrive in Australia around Christmas time 1959 and the wedding would take place immediately.

As soon as the ceremony and the festivities were concluded, Peter and Cecile drove off through Kangaroo Ground along the first path of the original route from Melbourne to the mountains on their honeymoon. By the time Cecile returned she was not only more in love with Peter, but was also in love with the Australian landscape. With only a short delay, she set about growing native plants, which she continues to do until this day on an ever-increasing scale. She knows more about the Australian environment than almost any native member of the country.

Two well established landscape people who belong or work in Eltham are Ivan Stranger, who now lives in Flatrock Road and has done many excellent landscapes, and Bob Grant, who has been the Eltham Shire Curator for many years. I van worked with an architectural firm and his transition from drawing large city buildings to creating landscapes has been a gradual metamorphosis that has been an inspiration to us all.

Bob Grant needs no introduction to Eltham. It is sufficient to mention that he worked with 'Rocky' Stones for some years and could have had a thriving landscape practice in his own right had he wanted it.

But he preferred to work as curator for our shire and his efforts there are a continual witness to his remarkable abilities. I am certain that there is no other curator in any other city or shire as good as Bob Grant. He has a natural gift for shaping land, planting trees, placing boulders, creating a continuing quality of landscape design that is not equalled anywhere else in civic or other public places.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >