We Are What We Stand On, Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

Author: Alistair Knox

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

I had set my heart upon an architectural career and in a way I had got it. But it was the first time I registered that the attainment of goals in life did not always give the expected fulfilment. At about this time, also, a Bible text had been consistently coming into my mind. It said in effect: 'Where much is given, much will be required'. My memory reminded me how much lowed to the wonderful childhood I had enjoyed and the wise and gracious conduct of both my parents towards their family, district and friends. My own life had seemed shallow and self-centred and I was becoming somewhat alcoholic. It may have been fascinating to others, but it was inwardly empty for me.

Over the next few weeks I went through a spiritual conflict concerning the meaning of existence. One afternoon in the car driving towards Melbourne the issue crystallized: I realized that two things stood between me and the life I believed I should be living. They were the realization that I had to give up my drinking mates and get back to Church. Giving up my drinking mates and returning to Church were the things I wanted to do less than anything else. My drinking mates included some of the most inspired and fascinating people in Melbourne. They were artists, writers, poets, sculptors, philosophers and the like who were the products of the preceding depression and war years.

I was involved in the great creative flowering that took place in Melbourne generally and Eltham particularly between the years of 1946 and the late 50's. In retrospect, it can be seen as a Golden Age of Australia. It was against this background I sweated out the cost of a spiritual commitment, which was gradually to change my outlook and the conduct of my life from that time forward.

One of the first things that started to alter was the amount of time I spent with those I had been so involved with in Eltham; I became more of a spectator than I had previously been. I still appreciated their creative and inspiring attitudes to daily living, and I still do. The alternative to which I was being directed looked dreary and very unfascinating from the outside. I was to discover that it was not so at all, but I have the keenest awareness of the difficulty people have in trying to put their foot back into a Church and rejoin with Christian people.

I wasn't encouraged either, when I finally made it with my three children to the dilapidated Presbyterian hall on the corner of Mountainview Road and Rattray Road, Montmorency, at 11.15 on a Sunday morning. We thought we were 15 minutes late, but were to find it was just about to start. As I sat on the corner of a wooden form trying to look as invisible as possible, I heard the preacher open the service by announcing that there would be a short meeting afterwards for the purpose of considering how they could set about building a new church building. To my amazement, I was to discover the first words I heard on my return to a Church was to be a job for me. We stayed for the meeting and as Bruce, (now Rev. Bruce Fraser) set out the problem confronting them, the answer crystallized in my mind in about a few seconds: I could see it as clearly as if he had held up an architectural sketch plan. A moment later, my daughter Gabrielle whispered to me: 'Get up and say something Dad, this is your stuff'. I rose, petrified and surprised, and meant to explain that I thought I may be able to help them with their problems, but the words that came out of my mouth were: 'I have been meaning to come back to Church for a long time and now that I'm back I mean to stay back'.

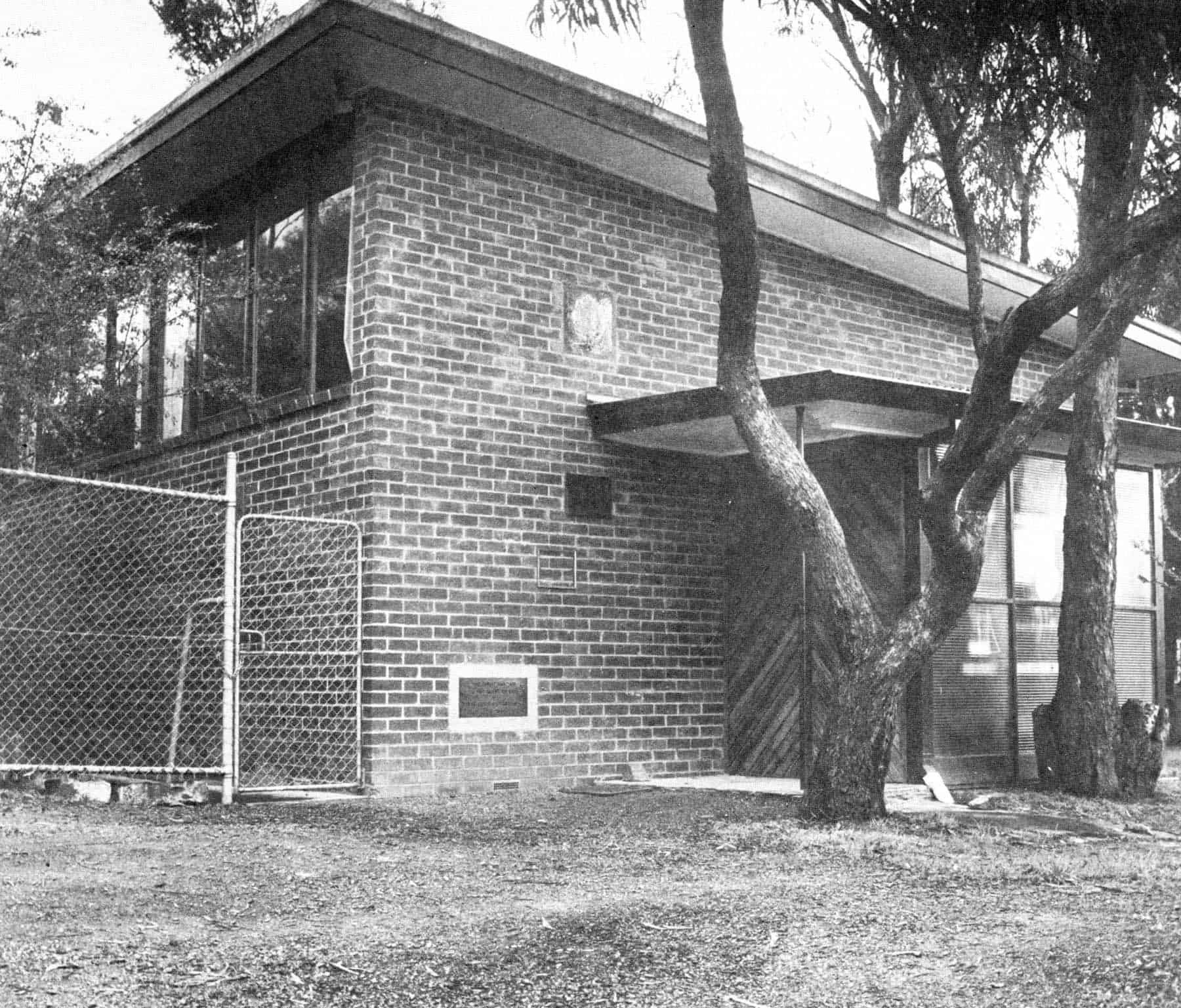

The Church Hall Montmorency - a place of spiritual resolution

The Church Hall Montmorency - a place of spiritual resolution

I then sketched in the best way to proceed, in some embarrassment at finding myself launched so quickly into a serious activity. There was very little traditional building possible at that time because of the shortage of materials and certainly a church building was an unqualified rarity. I didn't have time to assess whether the congregation consisted of second class citizens or not. I was too involved with my own problems. I noticed Bruce Fraser smile quietly while I was speaking and I was later to discover that this remarkable person, who was at that time an engineer in the Department of Civil Aviation, was a man who prayed for miracles to happen and was pleased as he saw them come to pass.

Events were to prove that I was the only person there who could arrange both finance and the building. God's timing was as perfect as usual; I needed them, and they needed me. Nearly a year later the building was opened on a beautiful Saturday afternoon. In the meantime I had become engaged with a superb group of natural, unpretentious people. I seemed to 'be the only second class person there. We had worked together in joy and harmony to bring the building about.

Several people remarked during that afternoon that it must be a wonderful day for me. I was not able to answer them because I was too busy controlling my emotions. This was the most worthwhile thing that I had ever done. I was full to the eyebrows, not with happiness, but with joy. Love, joy and peace are the fruits of the spirit and they were mine that day.

By the late 1940's an increasing number of independent strands of the mud brick movement united into one solid cordon. It moved stealthily outwards like a wily boa constrictor and encircled the whole community of Eltham. It was still a very local movement and no one thought about it becoming a force in the outside world, despite the great impact on our indig.enous community. It transcended the usual social divisions that often divide developing districts. We all felt we belonged to a special time and place. We had only one pub, one secondary school and one rule for rich and poor alike. Everybody counted, from the painters, the poets and the professors down to 'Metho' Mick, our universally accepted drunk.

One such independent development that was taking place was the Jelbart barn. It commenced before the war ended. This development comprised two of the biggest mud brick buildings in Eltham. The first, the Great Barn-as it was referred to was begun in 1945. It was inhabited by Ron and Yvonne Jelbart before 1950, although, like so many big personal projects, it was not fully completed until some years later. These buildings were situated _ in some 100 acres of land, which now comprises the Development Underwriters Estate called Woodridge. It is in the hills to the east of the village and entered through Pitt Street and Arthur Street. The Jelbart buildings are now on a six-acre land holding surrounded by modern project-type buildings.

A second strand was the buildings that I developed for Frank English, Macmahon Ball, Jack Holmes, Phyl Busst, Professor 'Dick' Downing and Dorian Le Gallienne as well as the Murphy's Creek Homestead, four miles from Tarnagulla in Central Victoria. This building was a significant factor in the mud brick movement because nearly all the recognised early mud brick builders had worked on it at one time or another. Another strand was that of John Harcourt, who was still erecting his pise-de-terre buildings in various places around the district and elsewhere, employing his automatic ramming principles. He built several sizeable houses of a personal character on the westside of the Diamond Creek, including the Roche-Pierson's in Diamond Street, the McConnell and the Danner houses in Swan Street, as well as completing his own adobe 'Clay Nunehan' fronting on to the Diamond Creek. His method of automatic ramming gave the houses a much more architectural character and quality. They had rhythm, form and structure simultaneously. It would have been interesting to see how far John would have gone had he continued to build instead of heading off to another State.

Montsalvat, which was originally responsible for initiating the whole movement, had reached a stage where the Great Hall was nearly complete and useable by the Master, Justus Jorgensen, as a studio and a gallery. Land on the west side of Bolton Street in Napier Crescent was being bought by Tim and Betty Burstall, Freddie and Verna Jacka and others at the dizzy cost of £40 a block on time payment at a rate of five shillings a week. Tim Burstall called to see me recently. When I asked him about his early days in Eltham, he proceeded to summarize his part in it for nearly two hours, hardly drawing breath. Tim has an intelligent, orderly - and strongly socially integrated mind. His impressive ability to recall the circumstances and analyse their consequences placed the whole of his experiences in Eltham onto one large canvas. 'Cliffie', he said, referring to Clifton Pugh, the artist, 'did not go up to Dunmoochin until a year or two after we started building'.

Dunmoochin is part of Eltham Shire. It contains the same tensile bushland, the twisted box and thin, straight stringy bark trees. At the time of it being christened Dunmoochin I offered an alternative name of 'Hunger Ridge' because I reckoned it carried about a lizard to the acre.

When Clifton Pugh decided to leave the city, he was drawn to Hurstbridge because it contained the nearest extensive bushland to Melbourne. He walked from the station; he had no other means of transport. He found that the high land he liked belonged to the Belots, the poultry farmers, whose property is on the junction of the Hurstbridge/ Kinglake Road and the Cottles Bridge/Arthurs Creek Road. The Clifton Pugh land was a series of ascending billowing hills which form a natural division between the Arthur's Creek and the Diamond Creek as they descend from the nearby Kinglake ranges to meet outside Hurstbridge and flow on to the Yarra through Diamond Creek and Eltham.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >