Margot Knox

Biography

1912-1929Childhood

The Bank

1930-1939

Adolesence

Marriage

1940-1949

The Navy

First Buildings

Bohemian Associations

1950-1959

Early Houses

Margot

Professional Building

1960-1969

Hard Times

Knox House

Landscape Architecture

1970-1979

Helping Hand

Eltham Shire Council

Mature Houses

1980-1986

Postscript

Clifton Pugh: Portrait of Margot Knox 1958

Clifton Pugh: Portrait of Margot Knox 1958I met Margot Edwards during 1948 in Matcham Skipper's Studio behind the Russell Street police station, and it was only a short time afterwards that I became her lover and a constant visitor to her in a loft in Ivanhoe. Margot was only eighteen years old and one of the most beautiful girls I had ever seen. She had done an art course at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and showed outstanding ability as an impressionist painter. I felt concern for my three children, who were now living with Mernda and her mother in a large, rambling, old timber house on three acres of highland that looked into the Eltham valley, which had not yet surrendered any of its rural village quality. But my senses were dulled because I had been in a sexual relationship with Sonia Skipper for two years prior to this event, and they knew all about my infidelity - which had been reciprocated by Mernda. The family was held together by Nina Clayton, Mernda's mother - a true surrogate mother who allowed the actual parents time to get on with their separate lives.

Eltham was further advanced in matrimonial deviations than was the rest of Melbourne; in the same way, it led in most other branches of twentieth-century social behaviour. Middle-class stigmas did not stick among its artistic community, which had always accepted personal freedom and personal licence as synonymous - a condition which was not to become the general standard elsewhere for at least another decade.

Margot and I had more than one temporary domicile in Eltham, including an old cable tram on Gordon Ford's property, before we moved into the Fabbros' cottage set in their vegetable farm on about twenty hectares of land on the southwest of Eltham. The main house was a traditional Italian farmhouse occupied by Daddy and Mrs Fabbro and their two sons, Jack and Maurice. The family has been a great asset to our district for more than fifty years. Maurie, the younger son, is now the sole survivor - his mother dying only recently, aged well over ninety. Her loud, penetrating voice could be heard in the quiet of the 1950s as it echoed more than a mile up the hill on the other side of the creek when she called Jack or Maurice in for their meals. Mr Fabbro was a small, olive-skinned, friendly, hardworking man. Margot and I rented the original cottage they had occupied in the early 1930s, when they first settled in Eltham during the Depression.

Margot and I were foundation members of the new Eltham society that had emerged since the war. Ours was a small, unique group without parallel in the history of Australia. The Peace had brought the potential for this new kind of society, and Eltham was the only community in Melbourne that had not opted for suburban progress. Its free and independent spirits were attracted to the Artists' Colony free lifestyle. We made every effort to keep living as simple and rural as it had been for a century. Eltham's valley location, formed by the oval perimetre of hills, made it a single entity that could be understood at one glance. There had one been three factories along Diamond Creek, which was originally an abundant mountain stream that meandered through its lowest level. Before the days of insecticides and increased human habitation, the creek's pure water originally had been used for brewing beer, then for grinding flour, and finally for tanning leather. As late as 1950, there were few locks on the houses because the majority of them were still under construction. Neighbours came and went at all times, in perfect freedom. It would have been possible to dine at a different home every day for a month, and then begin a repeat performance. The chief topic of conversation was the building of the mud-brick house, many of which had been partly completed for more than a year. The women were often celebrated and original cooks, and the major drink consumed was claret, which was beginning to replace the eternal swilling of beer.

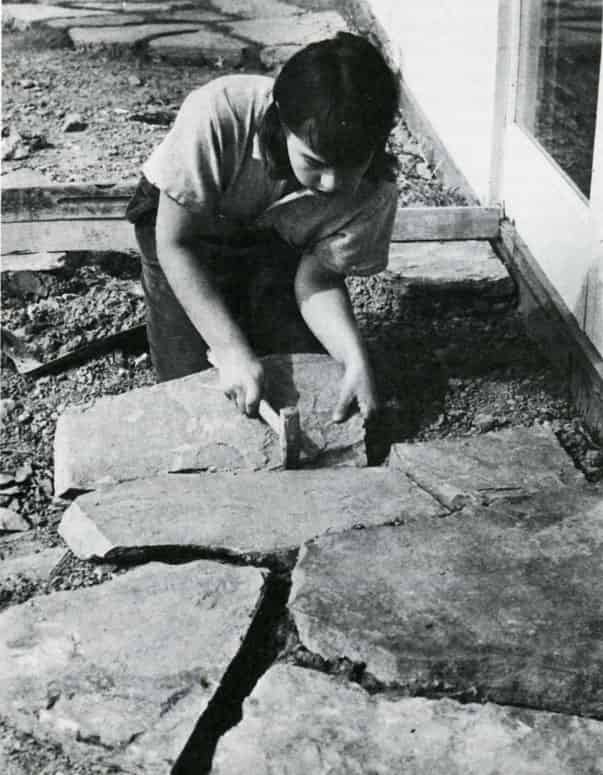

Margot was nearly nineteen years younger than I was, but she had a very able mind, and the eye and feeling of a true artist. When I first met her, she shared a flat with Prue Boilleo In East St Kilda, Prue was one of those very funny people who specialised in embarrassing her friends with her loud remarks in lifts and on public transport. Together, Prue and Margot were a rather formidable pair when they were in full flight in a public place. Their penetrating comments were as merciless as Barry Humphries's wherever sanctimony or hypocrisy reared its ugly head. When Margot and I first set up house, she still worked for Ellis 'Rocky' Stones, the original Australian landscaper, who turned her into an excellent slate-paver. Her young figure and beautiful face could stop the traffic at any job she was working on. We used to make periodic trips to Barkers Creek near Bendigo, where we would buy the slate directly for prices which even in those days were hard to believe. It was beautiful dove-grey paving material, which became a matter of great regret as we saw the supply dwindle. Slate was probably one of the last benefits of the goldfields, and one of the greatest gifts to the cause of environmental planning. Its heyday must have occurred before the turn of the century, when large rectangular squares of slate and bluestone paved all Melbourne's footpaths and redgum and jarrah blocks all the roadways. It was the vitality of natural materials and their creative use that supplemented the design concepts which, together with our quality of colour and light, made the environmental movement so human and satisfying.

Margot and I were very happy at this time, especially because I had become the acknowledged leader of the movement. It was still in its infancy, but it was turning Eltham into a class of its own when it came to creative building. There was only one cloud in this otherwise brilliant sky. The use of natural material is always more difficult than that of its manufactured counterpart which, without exception, would always arrive on site without any variation. Due to the unpredictability that occurs in natural stone and timber from load to load, I found it virtually impossible to allow enough percentage for unforeseen costs that might arise. The end result was that although we had built beautifully and left a trail of satisfied clients behind us, there was practically nothing left over for ourselves after we had paid wages. We regarded each job as an individual work that had something of us in it, so I just had to work harder and longer, carrying the bookwork in my head. Once again, enthusiasm and determination allowed us to produce the best at an extra cost of ten percent-plus. We watched as our growing imitators copied our ideas, performed inferior work at lower cost, and charged equivalent prices, so that they succeeded while we struggled. But the way of the innovator has always been hard, and individual building work is an exacting lifestyle.

Margot paving the terrace at 'La Ronde'

Margot paving the terrace at 'La Ronde'Margot became pregnant during 1953. The realisation that I would soon be the father of two families living in the same district was somewhat avant garde for those times, especially as I was a Christian and I also believed Margot was. This was before the sexual revolution, which would be in full swing ten years later. The prospect of the situation would prove less complicated than the actuality. Although I felt that Margot had every right to have children, a section of our community did not agree with this. It was to the credit of my recently found Christian friends, however, that they never in word, deed, or look gave any indication of disapproval.

When Margot's confinement was imminent, she went to stay with the Hattams in Canterbury. Hal Hattam was a skillful gynaecologist who also became a fine artist. ... Margot arranged to do slate-paving in the Hattams' garden, in exchange for her confinement. The whole social climate was suffused with a great spirit of doing and being. The residents had not yet become unduly rich and divided, and it was still difficult to decide who was becoming affluent and who was not.

Our first son, Hamish, was born in April, and we went to live in the farm cottage, where he quickly became the special object of Mrs Fabbro's concern and penetrating voice. I was working by the wood-fire stove one evening after dinner when a knock at the door announced the presence of two policemen. They had come to inform me that Mernda had been killed instantly by a hit-run motorist. As I recovered from my initial numbness and shock at the sorrow and the shortness of her life and its lack of fulfillment, I realised that a new era was opening up for me. After a suitable pause, I would, naturally, go on to marry Margot, and we would go to live with my other three children in my old house on the other side of the valley. When the wedding took place some three months later, a general sense of order and well-being had been restored. John and Mary Perceval were our witnesses at the Registry Office, and we returned to their house for a quiet reception which included Dick and Dorian, Gordon Ford, and our intimate old friends.

In 1954 Alistair and Margot moved into the family house with their son Hamish sharing it with the three children of his first marriage, Tony, Gabrielle and Eugenie. Mernda's mother 'Ninna' Clayton moved to a house she owned in Wattletree Road Hawthorn East. This arrangement was fraught with tension almost from the beginning. The elder children resented Margot replacing their mother and Margot found it difficult dealing with children who were not very much younger than her. This was solved by the children moving into a cottage at the rear of the property.

A couple of years later Alistair built a house for himself, Margot and Hamish on the front corner of the property which allowed them to rent the main house.

This house and office were the prototype for many of the houses he would build over the next few years. Numerous examples of these are found in Lisbeth Avenue, Donvale.

Their next two sons, Macgregor and Alistair, were born in this house. In 1963 a financial restructure and growing family saw the sale of all these properties and the building of stage one of the Knox house in Mt Pleasant Road, Eltham. Here the family continued to grow with another son, Alexander, and at last a daughter, Sophie.

Later additions were built to house first, Margot's mother, Peg, and later Alistair's mother, Margaret. Margot was the undisputed ruler of this domain and her throne room was the kitchen. Here the kettle was always on the boil as she made tea for the stream of of children, clients, friends and those seeking information on mud brick building.

This was a good time for the family. Alistair's reputation was constantly growing, money pressures eased somewhat, although he tended to donate generously to worthy Christian causes.

However, nothing lasts forever and in the late 1970s Margot left Alistair. The house was sold to a Christian couple with grand plans to enhance God's glory. Margot bought a property in Hawthorn and Alistair moved into the office at the front of the property.

Margot created a 'mosiac garden' in this house which became famous. She lived in here and tended her garden until her death from cancer on April 11, 2002.

In the early 1980s Alistair moved to Margot's Hawthorn residence and lived there until his death.

See Gwen Ford's tribute to Margot here