Environmental Building, Environmental building

Environmental building

Author: Alistair Knox

A Knox house nestled in the environment

A Knox house nestled in the environment

Environmental building is not method of construction or a manner of building. It is a way of life.

It will change its appearance in different countries and climates, but it will always contain the same spirit. No other country has as great an opportunity for the creation of environmental architecture as Australia because no other country has such a profound, unbroken, and comprehensive landscape.

The whole of the Australian sub-continent is united by a single element. This element is the power of sunlight. Its dominion stretches from coast to coast, from north to south, and from east to west. It unites the inhabitants scattered thinly over its surface because it dominates their aspirations and activities. It makes the great red centre a land of forbidding power. It creates a sense of water-hunger in the environment, which expresses itself forcibly in the primaeval forests and the gaunt, stick-like foliage of the desert. It is a land of hazy distances and sun-bleached colours - like over-exposed photographs.

The deep red colour of the ageless red gum along the rivers and swamps, the tenuous tough brown red of the jarrah, and the tremendous strength of the iron bark are all immutable examples of a sense of survival-consciousness.

Leaves that hang listlessly on the breathless, hot days are turned edge-on to the sun. They reflect a deep struggle to survive. This is the seal of the great southland - survival.

There are abundant forests here and there, but the sense of survival-consciousness carries through into them. They are grey-green and dun-colored. The form and character still express the dominance of one factor - sunlight!

Environmental building becomes architecture when it reflects this spirit and concept in its results. Examples are not, in themselves, complete works or architecture; they are elements in the landscape. United, they express the cardinal principle that house and land are indivisible. The sun-evolved landscape must extend into the building, which is man's acknowledgement of mystical realities infinitely greater in power and concept than himself.

The Huggett barn, Eltham. Photo: Tony Knox

The Huggett barn, Eltham. Photo: Tony Knox

Technological advances have, in most countries, caused environmental chaos and disorder. Most men no longer know what real landscape is. Each year the population explosion throws more shadows over it and tramples more of it into the dust.

Our survival depends on a few inches of topsoil on the earth's surface. Each year, this decreases. Mankind seems to have caught something of the dread disease that causes whales to throw themselves in schools onto the beach to commit suicide.

Ignorance of the understanding of environment has already had a disastrous effect on the Australian landscape. Private ownership has been permitted ever since the early settlements without much thought being given to the rights of future generations. The nineteenth century saw the rape of the great United States of America by private enterprise. The twentieth century is seeing a self-centred greed and ambition producing similar results in Australia. It is called 'development', 'prosperity', and 'progress'. It is for some - the few who control the land.

But the land is the heritage of all her people. And Australia is perhaps the one country remaining where there is a real liberty of opportunity, combined with space to operate, that could achieve a democratic and equal land use for all.

The cacophony of the twentieth century has put a great premium on silence. On the Nullabor Plains and in other parts of our horizontal spaceland, this privilege is still sacrosanct.

The history of building in Melbourne lacks the Georgian spirit of early Sydney. In addition, its climate and environmental being is quiet and more sequestered. The blue of the Hawkesbury becomes the mauve of the Yarra Valley. The power of straight sunlight is veiled in faint mists.

Melbourne atmosphere is at its best in the in-between times of the in-between seasons - nuance, not statement, its final quality. This creates a spirit of mystery which environmental architects must fully exploit if they are to create a sense of indivisibility between house and land. Such an architecture consists in stating in terms of structure what the landscape says.

If Sydney has had its Greenway, Melbourne has had its Griffin. Neither man is Australian, yet both expressed environmental character in their buildings despite the limitations of techniques, materials, and the times.

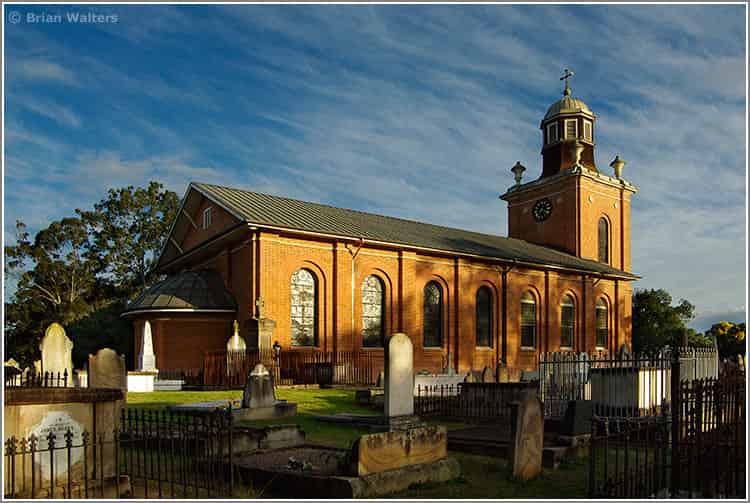

Francis Greenway's Saint Matthew's church, Windsor

Francis Greenway's Saint Matthew's church, Windsor

I believe the greatest individual building in Australia is Greenway's Saint Matthew's church at Windsor. Here the one-time embezzler put his remarkable abilities to a timeless use. He created a tower, square and strong, that looks over about seven miles of the Hawkesbury river flats to the Blue Mountains beyond. These rise even squarer and stronger. The imagination is fired by the creative understanding that makes bricks and mortar indivisibly a part of the timeless land.

Griffin lived in the Yarra Valley at Heidelberg for several years. Something happened under those millennial red gums in his front garden. He caught a vision that expressed in his buildings something of the cave, something of the relationship between sun and shadow, something of the power and the silence of the Australian landscape. What, then, does environmental architecture have which sets it apart from the conventions and formalities of the passing fashions?

It has a consistency of purpose, because it is based on an unchanging philosophy of the landscape. The prime experience in the Australian scene is a sense of power and inevitability. It cannot alter; its character is resolved and has moved beyond time. It is of all time. It has the eternal truth within it. Nowhere is this sense of the eternal more evident than in the hot, silent nights where the moon lights up the naked arms of the white gums and the stars shine through the motionless leaves. The struggle between sun, water, and land is passing through a period of truce, waiting for the return of the all-powerful dawn. The silence becomes almost audible, terrible.

Other than Griffin, it could be said that Melbourne had little indigenous twentieth-century architecture until the year 1947. This was two years after the Second World War. Building materials were almost unobtainable except on the market. Young men returning from the war were inspired to create new structures out of the ashes of the depression and the carnage that had just finished.

The desire to avoid the pretence of the past, coupled with the paucity of materials, produced an architectural cliché called the 'thin line'. Roofs became wafer-thick; window mullions were reduced to white wisps, machined to within an inch of their lives. A spate of skillion roofs appeared, ostensibly because they were cheaper - which was doubtful - but the final result was a very thin line, indeed. It was so thin that it finally disappeared altogether in the early 1950s.

In these circumstances, I turned toward the Eltham district. There it appeared to be possible to build in mud brick or adobe. Being earth, it was obtainable where other materials were not. No one actually said that you were permitted to build in each, but there were a few buildings of this material, either constructed or being constructed by private individuals, generally on large areas of land.

With a confidence founded on ignorance of local councils, I made application to build a small adobe house for a man named English in 1947. The Eltham shire did not have a building inspector or engineer at that time. A man used to appear once a fortnight who was regarded as a temporary engineer. My application to build was continually put off. Finally I set about building without further argument. Perhaps I though no one would notice in the bush.

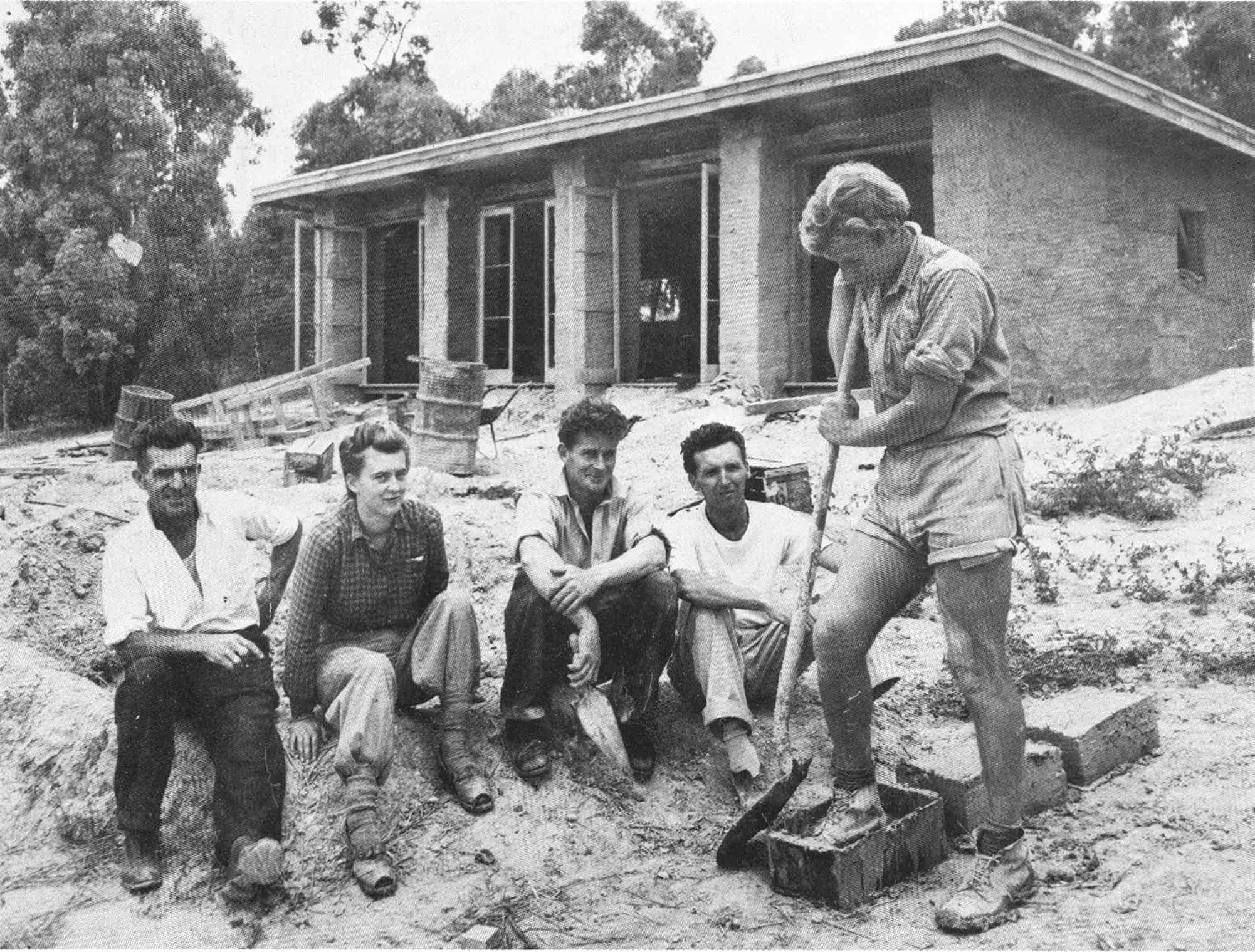

The walls were half-way up when a whisper got around that the permit would not be forthcoming! By chance on the very day the local councillors met to discuss the problem, a pamphlet on building in earth, issued by the Commonwealth Experimental Building Station, became available in Melbourne. I obtained a copy for each Shire councillor, which I handed to them as they returned from a substantial luncheon at the local pub. I pointed out the virtues of the material and swung the vote from No to Yes. This opened the way to the modern environmental movement in Eltham. One person who led this excursion into mud building was a woman - Sonia Skipper - who had served her apprenticeship in the Artists' Colony under Justus Jorgensen. I employed her as a forewoman. Reports of the English house were published in the daily press and in architectural magazines, and a hum of excitement rose over the quiet Eltham district. It took on something of the character of the gold rush. Men and women could be seen in clearings in the bush working furiously at making mud bricks. Everyone wanted somewhere to live, and materials for building were very scarce. The contingencies were varied and unpredictable. It all had to be done by oneself, with whatever help could be obtained, and no one really wanted to work; in addition, mud-brick making was just that - hard work.

The English house - the first mud brick building, 1947. Left to Right: L.Mayfield, carpenter; Sonia Skipper; Alistair Knox; Tony Jackson; Gordon Ford

The English house - the first mud brick building, 1947. Left to Right: L.Mayfield, carpenter; Sonia Skipper; Alistair Knox; Tony Jackson; Gordon Ford

Those who lived above a certain height on the east and west of the Eltham valley had to adopt ingenious and complicated methods in the making of the bricks. The water supply in the district was notorious. The pressure would fail as early as eight o'clock on those long, hot summer mornings that were crying out for mud-brick making. As the pressure dwindled, the hill-top dwellers would call out to those who lived a few chains away, 'The water's off!' This cry would precipitate a feverish activity to get enough water for every-day use. The supply would sometimes return as late as ten or eleven o'clock at night. Holes were dug into which a miserable stream of water would trickle all night to wet down earth for the next day. Stamping in and out of the holes accumulated large lumps of sticky clay on the old army boots that everyone wore. One group used to time themselves with a Big Ben alarm clock. A bespectacled member of this company was seen one day with the clock stuck to the mud of his over-size boots, searching everywhere to find out what the time was, oblivious of the fact that he was wearing it on his boot.

The English house was a simple house for one person. It had bush-timber main beams, mill-sawn roof joists, and decking. Four massive piers supported the beams, and on the opposite side a successful fireplace alcove set a character that was quite frequently employed later.

Some of the people employed in making brick and building this house have since become well-known men in their chosen fields; but the immediate postwar period was a time of indolence and restoration, and the building of mud houses was therapeutic. Some workers camped on the site. I remember calling one Saturday afternoon with the owner, to see how the work was progressing. We heard a scuffle as we tramped through the bush and caught a glimpse of men darting off in all directions in the pretence of having worked all day. One retired well to the bottom of the land and was seen digging furiously; closer observation revealed that his shovel was a frying pan! The end result of all of this was not uncommon to anyone who is an originator. Everyone was paid except me. The last payment for the completion of the house was not forthcoming because the owner had said (not altogether untruthfully), 'It's no good, Alistair; the boys didn't work'.

The next year, we started a house for a Miss Busst. It was a serious attempt to create an environmental building on a hillside on a northern slope on the west of the Eltham valley. Those who fronted-up are now well-known men. They were all drawn by the common magnet of the magic of mud. Not all environmental buildings are built of earth, nor are all mud-brick buildings environmental. The great quality of earth building is its flexibility and response to individual expression. It allows a layman of discrimination to build in terms of feelings, rather than being bound by a mass of technical rules.

The workers on this house included Gordon Ford, landscape architect; Neil Douglas and Peter Grass, artists and landscape architects; Wyn Roberts, the actor; and a remarkable man named Horrie Judd, who was destined through this building to become one of the traditions of the Eltham mud-brick scene.

Horrie has been making and building in mud for the past twenty years. Stories of his feats are legion. I remember Tim Burstall, the film director, discussing with this neighbor, a University lecturer, the possibility of Horrie excavating more earth than a small bulldozer in a given time.

Upper level living room, Busst house, 1948. Photo: Tony Knox

Upper level living room, Busst house, 1948. Photo: Tony Knox

The requirements of the house were two very large rooms, with an entry at the intermediate level. You walked up into the studio facing south and entering onto the garden at ground level. You went down into the living room and kitchen. The roof of the lower section was accessible from the studio. Every room had access to the outside without steps. To do this, it was necessary to pour a concrete slab floor. I took out a pencil and calculated the cost. It seemed no more expensive than the conventional method. Mobile concrete supplies had not commenced operating in Melbourne. Horrie scorned mechanical contrivances, anyhow! Gordon Ford stood on one side - strong, brown, and prodigiously healthy - with a square-mouthed shovel; Horrie, on the other with a shovel to match it. Together they turned over and mixed fifty-two bags of cement into concrete, and poured the slab in one day on the lower level. This would approximate about ten cubic yards with a dead weight of nearly twenty tons when wet.

I believed I had invented a new building medium, the slab floor, in domestic building. This was not so, of course. But I have been using it consistently since that time. It is interesting to see it become common practice twenty years later. The CSIRO turned their attention to slab design some years later than this.

They asked to see what I had done about waterproofing and the like; when I pointed out the simplicity of the method I employed, they tore up their proposals and started again. Earth building is like that: it makes you think creatively.

The low cost and natural beauty of adzed tree-trunks caused their use in the lower level, which had to support the foot traffic above. The upper-level ceiling was of exposed straw bound with wire. The building itself was bifurcated, and the entry was the pivot of the two levels. The straw roof lining could curve and flow both up and down and fuse the structure into the hillside. The solid 3' x 2' piers supporting the main adzed roof beams expressed something of the rhythm and power of the ancient apple boxes and stringy barks of the district. The window walls folded back against them, so that the inside could completely integrate with the outside.

A punctuation in the earth wall ran right along the south side of the studio, high up, to create a subtlety of light. It continued into the entry and terminated in the two wing walls in the living room that formed the fireplace alcove.

Terra cotta floor tiles were unobtainable at that time, so we made our own out of magnesite. They obligingly buckled a little after they were made, and provided a truly environmental rhythm to the whole. This building has stood the test of time. From being way out, it has become fashionable. Fashion may change again; but its simple, assured proportions will remain to express a sense of well-being and oneness with the environment. It is a genuine example of the indivisibility of house and land. The stone slabs which protrude from the piers are one of those details which come so naturally in earth building.

The only disappointing think about building in earth is that it takes years of experience to be able to calculate costs. There is a tendency to underestimate because the material itself costs nothing in the first place.

It cannot be questioned that modern environmental building originated in Eltham as a result of earth building. It was my good fortune to be the only person who consistently applied the medium to express the spirit of the landscape. It was a fortuitous circumstance of time and opportunity. I happened to be in the right place and I had a passionate love of the bush land. I was an Australiaphile and came from a pioneer background.

Just prior to the Busst house I designed and built the Periwinkle, a small building for two people. This building received a lot of notoriety at the time. It expressed the plastic use of this timeless material. The whole flowed together in horizontal and vertical lines, all based on an expanding spiral. It was successful, considering its time and cost. The cost, however, of sixteen hundred dollars was too much for the owners. We agreed to disagree over it. I never quite finished the building, and they never settled some of the cost.

I was discovering the hard way that cost-plus system had its faults - the fault of never being settled.

Interior, Pyke house, Templestowe, 1951. Photo: Kate Gollins

Interior, Pyke house, Templestowe, 1951. Photo: Kate Gollins

The following year I was commissioned to sub-divide a twenty-acre orchard three ways, then site-design and build four houses, and leave everyone happy. The material shortages here were a little less acute than in 1948. In design it was not difficult to satisfy the clients, a group of five or sex discriminating women who had elected to withdraw from Toorak and enjoy the country life of Templestowe. The execution of the work was more arduous and exacting.

During the succeeding years, they have watched the encircling city draw nearer to them each month. They have stood their ground. In my opinion, they made a wise decision. I was able to resolve the land sub-division, planning shaping and, to a reasonable extent, the buildings themselves. Costs were perhaps another matter, but this was still a common problem in specialised building. It certainly plagued me for many years; in fact, at times it still does.

Once you get the gist of environmental building - or, as it is in this instance, building in the environment - you never seem to lose it again.

The best of these buildings is the Pyke house. Guelda and her sister Polly were good and fair clients. I particularly enjoyed working for Guelda, who always kept bravely on despite a vague possibility I suspect she had: that the building would collapse. It didn't. As a matter of fact, when they called me in to design an extension more than ten years later, the whole development was impeccable - and she said so.

The extension made this large timber construction of laminated roof lines and clerestory lighting over 120 feet in length. The major regret, looking back, is that it was painted rather than stained. This was because there were no suitable stains available at that time. My wife Margot paved some of the living room - which in those days was quite unheard of. There never was a better random slate-paver than Margot, who is both artist and sculptor - and practical, to boot! True domestic building is a matter of feeling and construction - in that order. A house that feels right is right; Margot's paving added great feeling for that house.

All these buildings were on slab floors. This was the very early days of concrete trucks. Despite the misfortune of painting the buildings inside and out, three of them stand as reasonable demonstrations of environmental building, with pitched ceilings and a resolved landscape formation and character. Hessian walls made their postwar debut in them, and the flexible inside/outside feeling is real. A remarkable painter appeared to do the difficult Hessian and other finishes. He camped on the job. His favourite expression was 'Marn is an animal' in a Scot's accent, but his own work was more like an angel's than an ape's.

There were legal limitations to building sizes in these times, which tended to restrict seriously the space element in the houses. However, they combine a sense of determination, which is an essential ingredient in an architectural innovator, with the experience of dealing with a group of people with varying viewpoints on a common project. The result was salutary. It forms character, philosophy, and realisation that the future in environmental building would be tough. There would be no royal road to that goal.

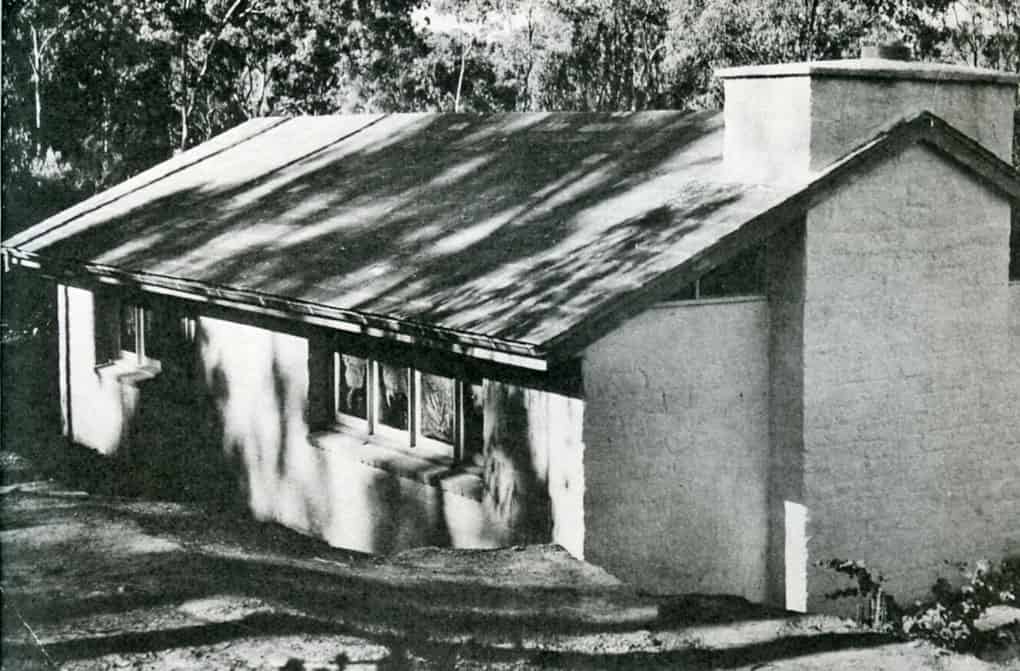

A welcome respite came when Dick Downing, a professor of economics, and Dorian LeGallienne, the composer, asked me to design an adobe building on rural land they had beside the river in Eltham. It was to be a weekend house. What a simple and gracious building it turned out to be! In environmental building, the personality of the clients must come through because they are part of the environment. Dorian LeGallienne was a man of genius. Both he, Dick, and I walked over their fifteen acres on Saturday afternoons to locate a building site. The unbroken environment drew us into a unity. The sense of antediluvian foliage, the trunks of the stringy barks, and the yellow box were unforgettable. The myriad bird life, largely unaltered since creation, moved about and sang with unconcerned joy. The evening star would rise, and the pale mauve-pink light of the Yarra Valley would cradle immortal visions in our minds.

Stage 1 of the Downing/LeGallienne house

Stage 1 of the Downing/LeGallienne house

Dorian died in 1963. He was only forty-six. His first symphony had not long been completed. It was a tragedy for the culture of Australia that its finest composer should die, to a large extent, through overwork. His only crime was that his creative genius was music - a financially impossible art-form.

I owe much of any ability I have to the genius of Dorian LeGallienne. He had a wonderful capacity to see value in things that no one else could. His witty and penetrating remarks opened up visions and ideas on every side.

The building I designed for them was so simple that I kept apologising for it. It was Dorian who made me see that simple proportions are the essence of environmental architecture. I was also to learn in the course of time that it is harder to be profoundly simple than to be profoundly complicated.

The seeking after a personal architectural philosophy found its destination in this fact. Hitherto, the attempts to be unusual or clever kept interfering with the expression of the power of the environment. From this time on, I discovered why I was doing what I did. I have practised this ever since. No doubt there have been many mediocre and even poor examples caused by financial limitations and the difficulty in earlier days of finding suitable people to do the work - and other factors. But I never sold out. In 1968 the whole architectural emphasis has shifted toward a national architecture. It was this ambition that kept me going in those early and difficult times.

Several men I have employed have since gone off and founded a quasi-environmentalism which bears varying degrees of relationship to the real thing but fail in the final test of environmental architecture - the placing and resolution of the building on the site. Environmental building is a way of life. In the elements of the land itself. The architectural fraternity have joined in it rather later than might have been expected. Some among this brotherhood have a tendency to get on to somebody else's good thing and stick to it. Perhaps it was all those glossy magazines that acted as a time buffer.

It is gratifying to look back now and remember how it all began. The one anachronism that remains in most quasi-environmental building is plaster. Plaster is the kiss of death to such building. The land is full of young men and women with ability and enthusiasm in spite of our false affluence. If these capacities could be rechannelled into the creation of new cities, instead of genuflecting to the false economic system and standards of today, we could even re-create a national Australian character, which was once the common prerogative of all our people.

As we rediscover the environment, there are other forces at work destroying it: international capital, and the persuasive daily press that keeps on telling us we are in an economic explosion. They forget to mention for whom this explosion is taking place.

There is no hope for any richly endowed country to be itself while it is under the control of international forces. Internationalism is the arch-enemy of environmentalism. They are diametrically opposed.

At the present time, in the once-silent spaces of the Northern Territory, the passive factors of a timeless land are being force back ruthlessly by the impact of foreign capital. Will it need to reach the dimensions of a natural disaster - like the rape of America during the last century - before we come to our senses?

Back in the early 1950s, none of these considerations clouded the issue. It was our golden age. It culminated in the Olympic Games in Melbourne in 1956. It was here that our embarrassed self-consciousness left us. It was here that we realised that the great world outside had nothing to counter our environment and the personal freedom we had, despite our mundane suburbanism. We were on a launching pad, as it were, headed for space out. The fuse was never ignited.

It was at about this time that Barry Humphries created Mrs Everidge and Sandy Stone, and we were able to see ourselves as we really were.

Looking back, it is hard to see what went wrong. It was as though, nationally speaking, we took the Mrs Everidges and Mr Stones to our hearts.

After the completion of Dick's and Dorian's house, I started to look for a formula that would be the basis of a national architecture. A formula that could repeat in various ways, creating a tradition-wide variation or a theme that could produce a street architecture or, more truthfully, a paddock architecture.

Ripe for development. Photo: Alistair Knox

Ripe for development. Photo: Alistair Knox

When we consider how the city absorbs the paddocks on its outer perimetre, we become conscious of how rapidly the recollection of what was can no longer be registered in our minds. I sometimes look at John Perceval's and Arthur Boyd's paintings at Oakleigh of some fifteen to twenty years ago. The open land and the wide skies have dissolved, and no one would ever know that they had ever been there. Instead, all we can see is a series of wide roads leading to the Chadstone shopping centre! No wonder Beryl - Sandy Stone's wife - got lost in Foodarama.

For a considerable number of years, architectural design had used a constant three-foot module. This had arisen through the tin line, with its fibrolite roofs and rafter space three feet apart. Window rallions supported each of these rafts, to make a simple rib-like construction. There was a sense of meanness about this three-foot module, so I took four as a basis. I have varied this in many ways. I have even gone back to three feet at times, or five, fifteen feet - in fact, almost anything, even varying the modules within the total plan. At all times, modules are good, yet not altogether infallible. They do produce a form in building which, provided it doesn't remain only form but is used as a basis for proportion, can become a dynamic cellular-growth pattern that can cover the widest variety of activity and visual opportunity available in any land.

Australia - with its vertical rhythms going on endlessly through its forests, crossing the silent, horizontal land - is more consistent in its sense of form in a deep, primaeval way than any other land. The complaint that it is boring is only made by those who observe superficially. They do not understand its subtleties, its essential understatement, depth, power, spirit, and unchangeable beauty.

Three-foot modular walls were being manufactured at this time, but instead of being made with four-inch material which would gauge with four-inch stud walls, they were made from six-by-two, and heavily over-machined. This, in effect, made them difficult to handle and to reconcile in terms of modular and pre-assembled building.

Despite the fact that these six-by-twos were machined to within an inch of their life, these walls did in fact create a climate which made it easier to begin building in a modular way. At this time, the concrete slab was just a twinkle in one or two architectural eyes. Nearly everybody thought they would be damp, cold, and hard.

It is strange how hard it is to break away from European methods in our building. This comes about because we do not observe our twelve-months-a-year climate and simple building conditions. Australia in building uses a plant-on method, not a gauging-out one, as in many other countries that suffer from a snow line and six months intensely cold and difficult weather. The sun, with its great power, has not been observed except as an enemy and an adversary. The reality of environmental building occurs through our knowledge of the land and its climate, which brings about the realisation that the simple way is best and that you never use two things where one will do. Australian architecture should major on the deletion of inessentials. This sense of inevitability goes with the timeless land.

Early in the 1950s I studied town planning at the Melbourne University. It was a new discipline as far as this country was concerned. The schemes to make an environment an added attraction to a highly-developed society embraced considerations extending from Ebenezer Howard to Le Corbusier and beyond. These aspects were largely theoretical and unrelated to the human factor which, after all, is the main reason for the whole thing. With the notable exception of writers like Jane Jacobs, there has emerged a theoretical system of living that has been applied to the lives of many, to their disadvantage - and, to a few, to their very great advantage. The whole planning notion is fraught with misconception.

It is a confidence trick which exchanges small and doubtful amenities for real landscape - using always the excuse of progress. The perpetual tension that must exist in a so-called democratic state between private ownership of land and a public use of land is always found in favour of those who own the land. It is a case of to those who have, it shall be given; and to those who have not, it shall be taken from them - even that which they appear to have. Town planning in Australia is not town planning for people. It is planning for people with property at the expense of those without it.

The new-found mineral wealth of Western Australia has, for example, created barriers for the typical resident of Perth. Its once-quiet grace has deteriorated in spite of the political shouting about prosperity. The average person for whom planning authorities have a delicious phrase - 'the work force' - finds it hard to acquire the standards they enjoy for prosperity. Rents rise, false land values rise. Big speculators hold off for even bigger rises. This shortage of land causes increase in price with a deterioration of living standards at the lower levels. This, of course, is common in all societies. However, the freedom and youth of Australia should be a notable exception. How strange - that of all countries, it is that which is most engulfed by these quickening tempos of a minority working to its own and - the few people who are making their millions and those who help them to spend it and follow after them at the cost of that democratic liberty we have expected as a permanent right.

The final difference between capitalism and socialism seems to be that the capitalists are better confidence men but poorer organisers. If socialism had the persuasion that private enterprise uses - or private enterprise a better social conscience concerning the distribution of wealth - an opportunity for a happy state would result. There is no chance of this, however. We can all sleep tight in our beds. The hidden power that supports these elements will fight to the death first. It is only the ordinary run of humanity that needs to continue to suffer. Ironically, it is their problems and chronic injustice that probably keeps them sane. Modular building is the essence of today's structural methods in both economy and character.

It can pre-plan form, and, to some extent, proportion a building. Using modular systems allows the possibility of architectural character in a democratic sense - where every house owner is a potential designer. Building becomes a matter of fitting the pieces together, and on-site, off-site planning and organisation. It resolves the situation. I spent several years on this modular building method because it was a very important one in the Australian scene.

Traditions had to be created, so that the difficulty of junctioning allied materials could have positive and repetitive answers. In the early days it was this junctioning of materials that caused so much trouble and awkwardness. There was no longer plaster to spread over everything that you didn't like the look of. The design today meant that you had to like the look of everything you did - and everything you did had to stand being looked at and being liked.

First Knox house - modular prototype - showing the central main beam. Photo: Tony Knox

First Knox house - modular prototype - showing the central main beam. Photo: Tony Knox

In the earliest buildings, I generally used a main ridge running longitudinally along a linear plan. Eaves were extended six or more feet, and gables were extended eight feet. The pitch was generally one inch and one foot, or approximately five degrees. This inch and a foot made for easy pre-panelling construction. It gave a gracious, laconic, upward sweep to the building. The roof membrane was generally, at this time, malthoid finished with creek gravel. It was necessary to form up gutter with these membranes. This caused an upward curve on the gables for the last two feet before they reached the fascia.

This upward curve gave the building a fairly Asian character, and it reminded us that Australia is an Asian land, after all. The simple fact of having to do this in the most inevitable way produced, inevitably, a sense of location on the land and its relation to its geographic neighbours. Substantial rafters were set into these ridges at four-foot intervals to form the shape of the ceiling inside, the support for the ceiling deck and the roof cover, and also the widened eaves of the verandahs. These beams were supported by simple four-inch by three-inch posts that formed the four-foot module of the window walls. The posts were left as they came, except a small rebate for glass. Where window sashes occurred, plant-on stops were affixed, which meant the whole could be built with a small amount of machinery by two men. This encompassed quite a problem on the environmental Australian building scene. Domestic building is the main source of Australia's architecture, and it is done best by small groups of people rather than by big industry. Where there needs to be a balance between the machine, the hand-wrought finish.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >