Australian Regional Building, Chapter 2: Greenway and Griffin

Chapter 2: Greenway and Griffin

Author: Alistair Knox

There have been only a few notable architects in Australia who are known by name. There are many who have created buildings of architectural character who are anonymous. Men who have brought a tradition with them and applied it to humble farm buildings and simple structures throughout the country over many years. There are others who have had a natural feeling for form and proportion who have built with their eyes, their hands, and their hearts. The early scene in all the cities and country bears living witness to this fact.

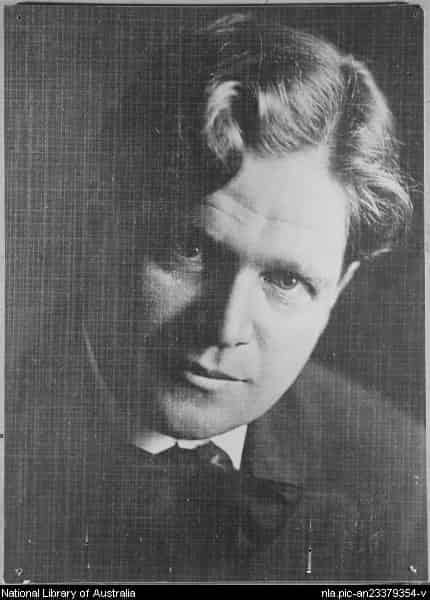

Walter Burley Griffin

Walter Burley Griffin

Francis Greenaway

Francis Greenaway

The two greatest names that emerge among recognised architects were both born in other countries. They are Greenway and Griffin. Greenway was deposited on these shores at the British Government's expense. Griffin came here as a creator of the plan for Australia's capital city, Canberra. Both had their own tradition when they arrived. Both expressed their concept of this country through an extension of that tradition.

There is a similarity in their work in that both attacked their problems with originality, clarity, and ingenuity. Both saw and felt Australia as something quite different from their homelands. They both experienced and expressed the strength of light and shadow and its importance in Australian building. This is a commodity which incidentally does not exist with international architecture, which continues to gasp 'Less is More'. May we ask, More What?

They both created emotion in materials, life in space, and dynamics in shadow. To stand at any point between St James' Church in Sydney and the line that connects it with the Barracks building on the other side of Macquarie Street is to feel the past century and a half fall away. As the eyes strain to read the dates and inscriptions on the pediments, the city's roar recedes. There seems to be a sound of a convict gang shuffling up the streets, and the sharp clack clack clack of horse-drawn vehicles. Greenway is dead, yet his work still speaks, recalling those days and at the same time looking into the future. It is concept, grand at any time, and too big for today's small, tight world. He was a visionary whose work was timeless. His sense of proportion based on a tradition became his own. And in doing so, it becomes everybody else's. It touches the deep common pulse that beats at the heart of all men. No one can deny his power, and no one else has been able to emulate it. His self-appointed scale comes through the bricks and mortar with assurance and character that time can never annul.

The Australian architect would be much better employed studying this master than flipping over the pages of the architectural glossies. It is no easy matter to decide why it moves us as it does, but absorbing it develops the feeling.

It is not by chance that the two greatest Australian architects were both masters in the use of brickwork. They consistently used subtle repeating patterns in the handling of bricks. They swung away from regarding them merely as a method of building substantial walls. They exploited pattern and flow to demonstrate their appreciation in the use of shadow in the sharp, clear Australian sunshine. It emphasised their belief in proportion and gave that new Australian additive to architecture: SHADOW.

The Lippincott house Eaglemont. Photo: Tony Knox

The Lippincott house Eaglemont. Photo: Tony Knox

There is no denying that Greenway was a strange man. He was ambitious and over-reaching, and apparently could be troublesome. When asked to design an aviary on one occasion, he produced a plan that was more like a crystal palace than a birdcage. Still, this character seemed to go with the times of seizing the main chance. His monumental lighthouse at Vaucluse still stands impregnable. And the crenulated battlements of the Conservatorium of Music, which were once the stables of Government House, give ample evidence of his capacity both to persuade and to perform.

The immortal churches at Windsor and St James' stand for all time. Their most unmatchable ingredients in these transcendent works are a combination of the exploitation of light, shadow, and pattern; perfect proportion; and the handling and use of bricks and other materials. Greenway, in common with every great architect, had the capacity to inspire his workmen to infuse imagination into material. He did it as every other worthwhile designer has: by keeping close to his materials. Frank Lloyd Wright understood what it meant to sleep among the shavings. Greenway understood the convict, because he had been one. The work they did for him indicates he had the knack of articulation. He changed the horror of their situation into hope. It was his vision that transported the transported.

Griffin came to Australia for the express purpose of carrying out his design for Canberra. The frustration and complications that bit into him finally turned him away from the project. Meanwhile, he was carrying on an architectural practice in Melbourne. Much more is known about Griffin than about Greenway. He was interested in a wide variety of people in a way that Greenway could never be because his opportunities for executing work on their behalf were much greater.

The small six- or seven-square house that Griffin erected for himself in Mossmann Drive, Eaglemont, still stands. It is hidden away behind a fibrolite building which hides it from the street. It is a square structure with the roof sloping up from each corner into the centre. There is a slight flavour of an Indian tent about it. Griffin's wife, also an architect, was half Indian. Inside, two wing walls protrude from each outer wall into the main inner space, which is otherwise undivided. Some of these were sleeping quarters. They were divided from the main living area by leather curtains. The building was constructed from knit-lock tiles, which was an invention he brought with him. It gave rhythm to the walls by creating a system of integral piers at modular intervals. The ceilings, as always, followed the line of the roof. He employed a window fastener that must stand as the simplest of all time. It was a nail driven into the top and bottom of the mill-sawn sash, with another nail for a lock, and that was all. They were still operating twenty years later. Internal doors were three oregon boards lapped over each other, with rails top and bottom for the flap hinges. Griffin came under much criticism later in his career for faulty building methods in some of his work. The fault lay rather with those who failed to understand what he set out to achieve. No one had a greater ability to build with vital structural stability, as the Capitol Theatre and Newman College testify.

Pholiota the house Griffin built himself and Marion, his wife

Pholiota the house Griffin built himself and Marion, his wife

Griffin had a passion for beauty, irrespective of cost. He never fell for the theory that economy means dullness or that aridity of concept indicates wisdom. He believed that beauty wasn't the prerogative of all, and he set out to demonstrate it in every building he did. He never meant some of his cheaper buildings, such as his own, to last forever. He was living in a world that desperately needed the banner of love for beauty to be borne on from the more spacious past. And Griffin was that man. Of course, he did not stop there. That was where he began. He caused building to become an altogether new thing in this country.

It was Griffin who rediscovered the sense of cave in the Australian dwelling. He exercised the same penetrating understanding of shadow and timelessness that can be seen in Greenway's work. He used to sit outside his Eaglemont house, musing, under the enormous red gums that raised primordial trunks and twisted boughs over the Yarra river valley. It was historic ground. Thirty years earlier Roberts, Streeton, Conder, and others created the Australian impressionist painting school in their historic nine-by-five exhibition in that identical paddock. The tiny hand-made pink brick and slate-roofed cottage that they used to rent was still standing in his view, half a mile to the south. It was there that Griffin indulged his passion for Australian flora. It was there that he discovered the secret of overplanting. The first time, possibly, in history, lemon-scented gums were planted in groups of three, within inches of each other.

At a later date in Sydney at Castle Crag, he was to rediscover the dynamic use of sandstone. In all his work, imagination and power went hand in hand. What he said, he said with repetitive organic force and fervour. Possibly the most brilliant house he produced in Melbourne foreshadowed, and in many ways overshadowed, Castle Crag, which was built at Balwyn. Something of its original statement remains. The tragedy of it is that so little inspiration had been picked up by succeeding architects. Heavy, complicated series of heavy horizontal strata floor flow out from the centre of the structure. Vertical lines carry up through these, and themselves terminate in horizontal parapets. The idea of walls gives way to a series of wings running at right angles to outside of the house, leading the eye and the feet from outside to inside, and vice versa. This inside/outside motion is the common cliché today. It has never been done with half the skill of the originator of the notion; here there is power of belief and expression timelessly performed. Squared random stone-work formed buttress bases to the structure. Below lay pools of cool water. All this in 1925, too!

Both Greenway and Griffin suffered the fate that is generally reserved for prophets in their own country and among their own people. With that unerring sense of injustice that follows visionaries, they were cast out, as surely as any Old Testament prophet. When Macquarie returned to England, the grand schemes that were afoot dissolved. Favours and opportunities fell to others. Greenway's nature didn't help. Some years later he took up land on the Hunter River and disappeared from view, never to be seen again.

With Griffin, the case was different: whispers rose to shouts. His buildings leaked. His structural methods were faulty. From being recognised as the leader of his field, he became discredited. His Canberra vanished behind a pile of papers and a mountain of prejudice. It is strange to see it in the open again fifty years later. The critics have at last caught up with him. The fact that they drove him from the country matters not one whit. He is well dead now, and no honour is too great to bestow.

Government House, Bennelong Point, Sydney,

Photo: Wikipedia Commons via Sardaka.

Government House, Bennelong Point, Sydney,

Photo: Wikipedia Commons via Sardaka.

It appears certain that if Griffin had lived in Australia before he designed Canberra, his plan would have been different. His strong axial layout may suit the reigning politicians, but the renaissance sense of row planting and the avenue would have been lost in the wonder he discovered at Heidelberg as he planted paper barks and lemon-scented gums against the indestructible trunks of the great river red gums.

Both Greenway and Griffin would have left memorials to the Australian countryside of its influence on them. Both reflected the joy they felt in the Australian sun and pure air. They patterned and folded their brickwork instinctively to catch what they felt and handed it on to posterity in the stones they inspired with life. They created portions which speak of the timelessness of the land and the struggle of man to survive in it. They both conveyed a high sense of seriousness in their work, conscious that the land they had adopted had a dynamic future and that their works were to be lighthouses flashing messages from the past far away into the distance. They spoke a universal language that all who run may read.

Today it is popular to imagine that the sterility of the international style has the universal message. If it has, it would be better left unsaid. It may be all the old world has to offer, but it is unprincipled villainy to force it onto the new. Or has the new so slowed its tempo and lowered its standards that it admires this false god of technique at all costs? Has that young, vital land withered so soon? Greenway was not the only inspired architect of his time. There are a variety of men who designed and built with dignity and style. Their forms were classic, their expression of it Australian. The columnaded form of Parliament House in Sydney and the Medical College in Macquarie Street are good examples of this.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >