Living in the Environment, Country Houses

Country Houses

Author: Alistair Knox

John Serle, an artist who had planned to spend his life painting in and around the rain forests of Queensland, returned to Melbourne after a year or two because of the call of the pale yellow clay in Eltham with its mysterious landscape and its nostalgia evoking views. At one time, John had been a driver of a council grader for the Shire of Eltham. He understood earth shapes and had done sufficient building in natural materials to be a sitter for the alternative society. He came to me and said he had some $3,000 and ~ fine piece of land in St. Andrews overlooking the Kinglake range.

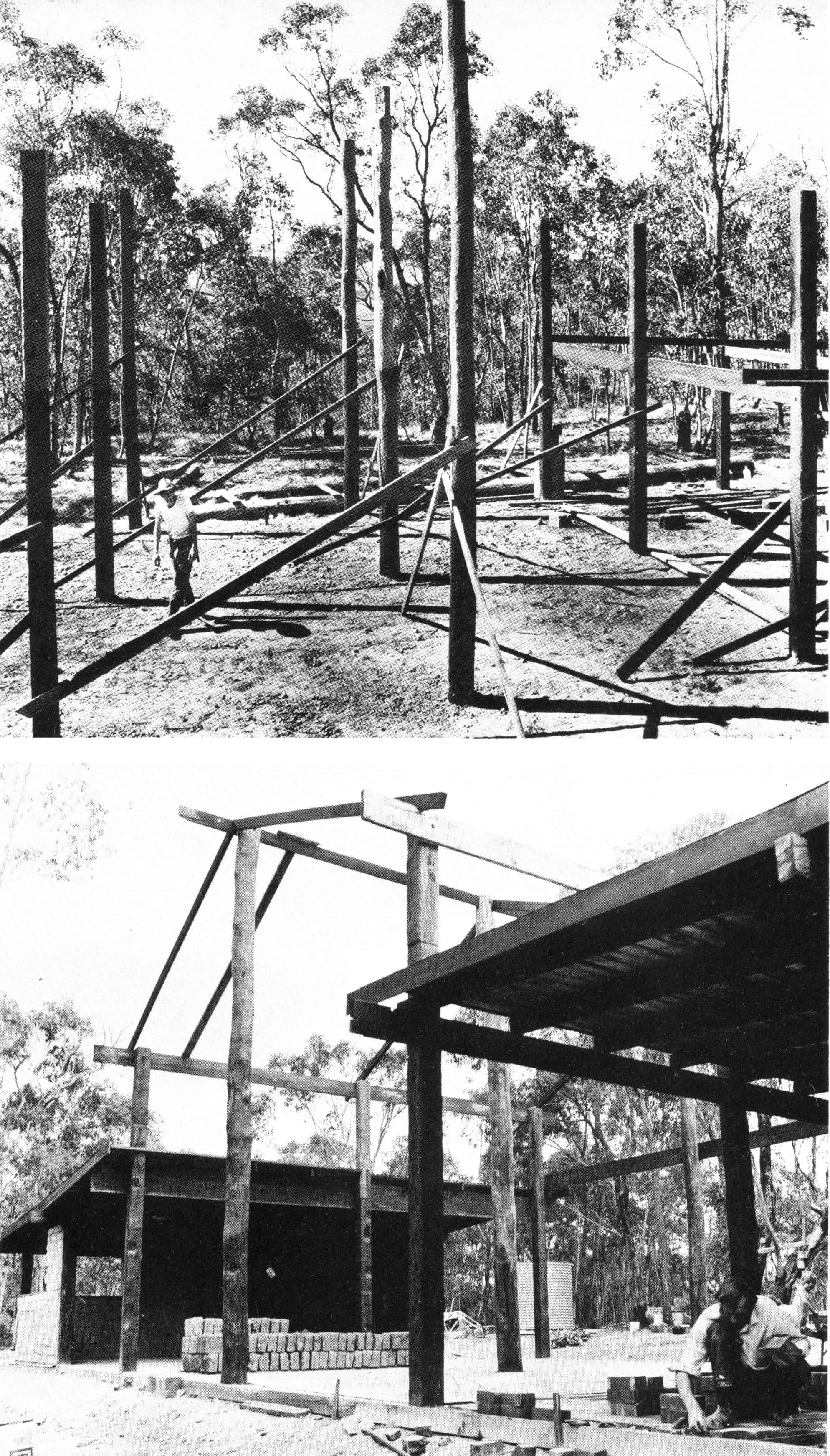

TOP: Johns Searle house using adzed post and mud construction. The framework

TOP: Johns Searle house using adzed post and mud construction. The frameworkBOTTOM: Laying the floor

St Andrews is an old goldmining town about twenty-five miles from Melbourne, with the main street about a mile long and practically no buildings left in it, save a pub at one end, a school in the centre, and a shop or so, and an old de-licensed hotel at the Butterman track end, which is being used as a residence. Incidentally, there once was a butter man and he used that track!

I designed a house John could build in stages that would provide him with a way of life at the same time. He devoted five or six months of hard labour and application to it. As time went by, he took a few short cuts and did a few unplanned things to it. But in the main, it was a good example of doing your own thing. He then built for somebody else. He has been bitten by the building bug. Everyone does when they do this sort of work. His building was planned with nine squares each twenty-four feet by twenty-four feet, forming a total square of seventy-two feet by seventy-two feet. This was again divided into twelve 100t modules. The four twenty-four by twenty-four feet squares, one in each corner were designated courtyards. The structure therefore became cruciform in shape. Light was brought into the central square by raising it to another level and allowing it to penetrate from above. The work was largely done by John himself. After excavating, his first work was to procure an adze and dress a series of posts set into the twelve foot modules. Some were square red gum, others reclaimed electric light poles. The tallest rose more than twenty-three feet above the ground level. John raised them himself. A series of draped roofs were then erected over three of the twenty-four feet squares. The brick floor was laid direct onto the ground. Earth and window walls were completed square by square.

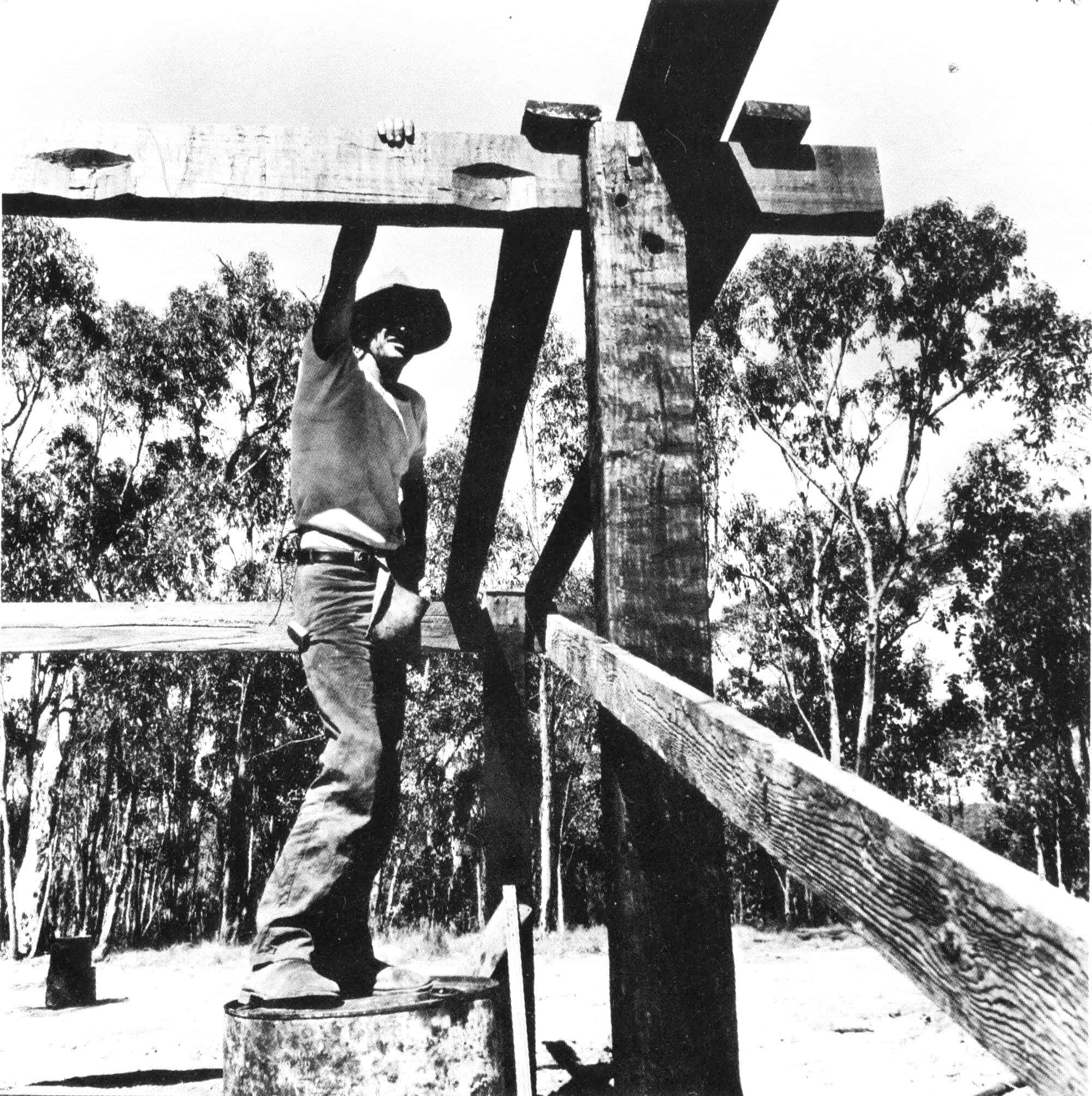

John Serle's vernacular hat

John Serle's vernacular hat

I would call out to see him, especially in the early stages, to advise him how to proceed. I was impressed by his ambition and tenacity. He and his family were living in a caravan on the site. It must have been something of a nightmare, the thought of erecting some three thousand square feet of building on one's own against a time limit. Of course, he soon accepted advice to borrow some money and employ a mud brick maker and some casual labour. At it was, he became a little thinner as the work proceeded, although when he started he was a fairly gaunt and rangy Australian figure set off by the most vernacular felt hat in history. Of a late afternoon, we would sometimes sit while the billy was boiling on the fire in the open and talk in monosyllables, gazing out from the scrubby eucalypt-topped hill.

The Kinglake range lay about four miles to the north. Between it and us brooded a mysterious valley. In that valley a hundred years ago, thousands of Australian and Chinese gold seekers worked unremittingly among the ironbarks and lived in shanties along the tracks. These still bear the names like 'Red Shirt Gully Road', 'Salter's Rush Road', 'Wild Dog Creek Road', 'Yow Yow Creek Road' and there was even one called the 'Chinaman's Track'. As we sat there, a century dissolved before our eyes. Nothing had changed in spirit or fact one iota, and now John's mighty posts and timbers were perpetuating the great pioneering traditions.

There is an indefinable understanding when we construct with such materials on an environmental site, that we are contributing in a short time for all time to man's sense of eternity within the eternal landscape.

One early summer's day in 1965, I received a phone call from Don Richardson who has the largest cattle station in Victoria between Omeo and Mount Hotham. The homestead had just been burnt to the ground and he wanted to discuss with me ways and means of rebuilding again, and in earth. Within half an hour, he had called at my house and a few minutes later we were arranging to leave for Cobungra at first light next morning. He was a man of action!

The station concerned, Cobungra, covers some 130,000 acres. It extends for about twenty-five miles one way by about ten miles the other. It is situated in some of the highest country in the State, and has all the mythical Man From Snowy River elements within it.

As Don and I came over a hill approaching the property, he pointed out a mountain just visible on the horizon and said: 'That's one of the boundaries'. Shortly before we had wound our way up the Tambo River from Bairnsdale to Omeo. We passed over a new bridge near Ensay. I asked Don to stop, realising that there must be an old one nearby. When we found it, I gauged there was some interesting timber to be salvaged for the new homestead. After the arrival at the property, I found the home plain to be about three miles by three miles of generally cleared land, subdivided into paddocks. There were the usual subsidiary buildings and. out-houses and barns, a shearing shed and a variety of holding yards for cattle. The land itself was bounded on the west by heavily wooded mountains, Cobungra Hill on the north, and elsewhere by a series of undulating hills, including beautiful Mount Pleasant in the immediate foreground. As I admired its ancient worn-down shape and feathery bush along the upper reaches, I saw white flecks on open country lower down its slopes. These turned out to be enormous mushrooms in astonishing abundance engendered by the late spring rains. The home plain was generally about 3,300 feet above sea level.

I had to select the site for the building on this 130,000 acres in one afternoon. By a process of elimination it was not difficult to arrive at the best one. It was situated at a sensible distance from other buildings and the site of the burnt-out homestead. It occupied a commanding view of the home plain, and was adjacent to the two airstrips. It cut a mile off the journey from Omeo by approaching in a more direct way. It was located in a sunny situation which was very important in so cold a climate. It stood on an all-round hill, one of a series of all-round hills of approximately the same elevation. There were two streams, one on either valley on the side of this rise. We planned to dam both of these streams to create artificial lakes and secondary water supplies. The new road actually crossed one of these dam banks that form one of the lakes.

In winter at this elevation the temperature can drop to about minus ten or eleven degrees Celcius. A major consideration was, therefore, planning for warmth, sunshine and temperature control.

As the homestead was a heap of ashes, Don and I drove back to Omeo to spend the night at the pub. It was there that I got my first inkling of the instinctive communications code that exists in those isolated places. A rather dignified story-telling, oldish man regaled us outside the pub with a few gossip yarns interspersed with a request that Don let a certain mutual friend know that a lease the storyteller had sold him a year earlier, now had certain charges due on it. If not paid within seven days the new owner would forefeit his rights. The friend lived miles away from Don and although most unlikely to see him, he agreed to let him know. The old man also said 'And get him to return that chestnut horse of mine as well!' His request seemed impossibly remote.

Early next morning, Don and I went 20 miles towards the summit of Mount Hotham looking for slate for paving that Don thought was lying around somewhere up there. Not only did we see this, but we saw two other people and they were the only ones we needed to see. The first was the man in control of the Country Roads Board for the area. We arranged with him to get the bridge timber for nothing! The second was the man who had to pay for the lease. Don introduced me then mentioned the expiring lease casually. 'I'll go over in two days' time', he said. Then Don quietly mentioned the problem of the horse which had been with him for about a year. He arranged on the spot to ride over on the animal to return it. It was fascinating to see how it worked, but Don just gave a little laugh as if to indicate that the laconic and instinctive Australian communication system known as the 'bush telegraph' was still very much in existence.

The Omeo-Snowy River high country of Victoria and Southern New South Wales is legendary for its men, its horses and its cattle. It has a history written into the nameplaces as you drive over the mountains to it. Names like 'Jim and Jacks', 'Whisky Flat', 'Flour Bag' and 'Mother Johnstons' reflect the struggle of those early days.

At Cobungra, scientific means are used in animal husbandry but there is still no substitute for the horse and the old ways when it comes to the real battle with the environment. As soon as we arrived, Don had assumed command like a captain going into battle. A wide variety of orders were issued concerning the organisation that had been waiting for him to make. Men went swiftly on horseback in different directions. The whole operation was a strategic battle with the elements and the weather. When it started to rain fairly heavily that afternoon, the orders had to be changed and a new plan of attack initiated.

We were nearly home after the 'bush telegraph' incident, when we were confronted by a drove of some five hundred heifers clipping up along the dirt road to spend the summer in the high plains. They were Don's beautiful Herefords and were controlled by the station foreman and a professional drover, more like Clancy of the Overflow than Clancy himself. There was a complete absence of whooping or yelling as they were guided past us. There was just a gentle, silent persuasiveness about the whole manoeuvre that had its roots in the magic of the high plains and the power of men's minds over animals, distances, and other natural obstacles.

In many parts, the land had lost much of its original growth through overuse from the early days of poverty and bitter struggling, or through the fires and rabbits. The pauciflora (snow gum) is the main tree of the area. It grew so densely following the 1939 fires in many parts, that it is impossible to pass between the trunks of sapling trees. At fairly close intervals, the big original specimens remained to indicate the savannah-like country of the original landscape, which has been so altered by the depredations of men.

It must once have been good pasture land, but a rapacious attitude had caused it to be over-exploited. The rabbits and fires had done the rest. Yet the land can restore itself if man can restrain his senseless desire for quick profits with suicidal long-term results. It is sad to reflect on what has happened to the tremendous and ancient land in the name of progress during the past 100 years.

The plan for the house consisted of a central courtyard room thirty-six feet by twenty-four feet with a high ceiling following the low pitched roof shape with clerestory lighting all round surrounded by a periphery of rooms and verandahs. It was not unlike my own house at Eltham. Two fireplaces situated at diagonal corners were not originally intended to be the main source of heat, but that is what eventually happened. The pitched roof was necessary for the snow. It was also necessary to provide wide, extending verandahs round the house without breaking the roof line. The timber retrieved from the old bridge was used for the main rafter system which was left exposed by lining above in timber to form the ceilings. External openings in the wall were nearly all floor to ceiling, and in three foot modules set in pairs making them six feet wide. Wooden shutters were planned to control these windows in extreme conditions, but were never used because the earth walls, the slab floor and the insulated ceilings did the job without them.

Don imagined himself a rather gay confirmed bachelor, but I had other ideas. Under the disguise of designing an office in con junction with his bedroom arrangements, I made allowance for a suite for connubial bliss. My guess proved correct. As soon as he took up residence he would realise how necessary it was to have a wise and gracious female to help him run that project. Before the building was completed he was engaged to be married.

Environmental building, acts on the whole man. It makes us see new visions and dream new dreams.

His wife had a scientific training and an environmental background, an ideal combination for her new position. And now, despite droughts and difficulties, children and families arrive and the essential renewal processes of human ecology take place, as man fulfils himself in many ways.

Only a handful of men can control a great station like Cobungra and live in that dramatic "landscape. But there are innumerable people in Australia who could live environmentally and who are frittering away their existences in dreary circumstances because we, as a nation, have forgotten the great privileges available at a purchasable price in the ancient land. It is possible to have an environmental way of life in a small area, even in a suburban allotment of say, sixty feet by one hundred and twenty feet, if we go about it in a sensible manner. This happens only because of the survival-conscious character of the indigenous growth. Two years of growing in general circumstances is sufficient time to allow bush character to come back to a sufficient density to hide the street from the house and recreate an area of planned, but natural environment. It can be strong enough to give our lives a new option.

With the landscape goes the indivisible house, sitting on it and at the same level, and so integrated with it that all is one, except that inside you have a manmade roof and outside the canopy of heaven it-self. But at night as those constellations wheel through their infinite courses they are also seen through the glass walls, and we can lie snugly in our beds and look out in the same way as a pioneer could see them as he lay under the open sky on his way to the diggings more than a century ago.

The urgency to return to natural living is strong in the hearts of many Australians. But they have to defy the whole materialistic gearing to achieve it. Individuals can and do make the break, but society stands perlexed and hesitant. It is sowing the seeds of its own destruction on the one hand and is scared to push out and away from the shore on the other, but push out it must, or go down in the shame of its own inertia.

One is very aware of the real poverty of life in Australia on the slopes of Mount Hotham and on the Cobungra High Plains, not because everyone has to be a station hand or a station owner, or even to live there in those impressive spaces. It's the air and the sky and the power of the sunlight, written into and over and through the flora and fauna that satisfy our vision, both inward and outward. We have an unbroken landscape in spite of what we have done to it, that unites us with the eternal purposes of creation. Not as useless pantheists, but as beings made in the image of the Creator, and able to share with Him in His creative purposes.

Some eight years after Cobungra, Dr. John Nicholas, an educationalist, asked me to plan for him in Canberra. He had lived in Eltham for years before he went to Canada. He was an ardent admirer of Frank Lloyd Wright. He had seen many of his buildings and assured me, much to my egotistical delight, that there was no-one else who could design his house for him.

I went to Canberra to study various sites for the building. Some were in the Australian Capital Territory and some in the magnificent Murrumbidgee Valley close by, The Canberra leasehold sites were in good, rugged Australian terrain but it made a very expensive method of living in an environment. It was worth more than $20,000 for a leasehold acre. In addition, the planners seemed determined to force it back into the repetitive character of the rest of the city. The same sort of roads despite the wider landscape, all the conventions - the sameness of a city planned by minds who see people as ciphers to be designed into an environment at the rate of so many to the acre. They are then separated by open spaces but this tends merely to further isolate groups of local inhabitants from the life of the total city. As Canberra grows there is an ever-increasing series of social hiatuses where people can go mad with inner loneliness, the victims of a modern disease known as Planners' Pencils.

John Nicholas is a member of the 'new education'. He sees it as a process which keeps people whole, while it expands their vision and potential. He soon saw that though the Canberra sites were good for Canberra, they were not comparable with the Murrumbidgee landscapes a little further out.

It was also true 'Man from the Snowy River' country. Rocky outcrops where the stockman's pony struck sparks from the flinty outcrops, were on every side. The Wombat Ranges encircled it; further to the south rose the Brindabellas to form a beckoning horizon of great power. That everchanging pattern of light and colour makes us emotional as we gaze at it. We are in the midst of the man and the myth of the high country of Eastern Australia.

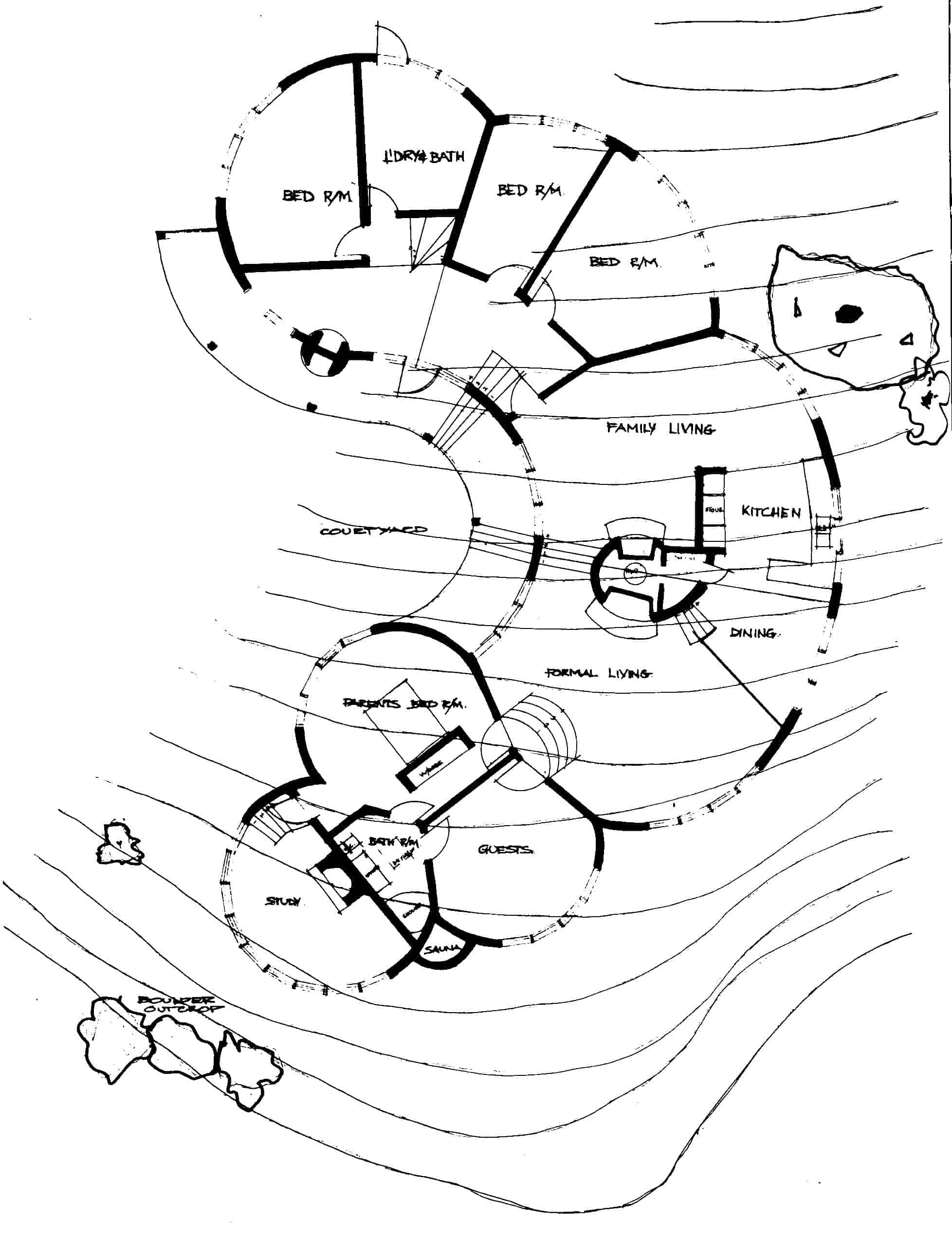

The original sketch plan of the Nicholas house in Canberra

The original sketch plan of the Nicholas house in Canberra

It was situated about five miles from the Australian Capital Territory in distance and about a million miles away in spirit. The broad sweeps of the river below vary from stony bars to wide Murray cod pools. The yellow box and stringy bark make a savannah landscape, but the Casuarina Cunninghamiana on the banks is the special quality of that landscape. Its subtle yellow-green is as indigenous and friendly as the ubiquitous Pinus Insignus is sour and alien. The craving that the State Forestry department evidences for pushing over our natural landscape to fill it up with the dark, foreign pine plantations, is unforgivable. The argument that it is economic is doubtful, but there is no argument against the fact that it is destroying our natural environment. What damage it will do to the landscape in the end has yet to be discovered. When it is, it will be too late to repair it.

I knew that John Nicholas was expecting me to produce a virgin design on the rocky outcrop we selected for it. We sat on one of the mossy boulders that covered the sloping site which was about one hundred and fifty feet each way, but tapering to a point as it sloped down the hill toward the river. The edges of the outcrop then fell away steeply. There were several problems. The winter sun shone one way, the best views were the other. Then John wanted a pretty involved building at a 'not-tao-involved' price. There were to be many rooms, yet it had to be spacious at the same time. The plan needed separation and union simultaneously.

He was a thorough, file-keeping person. My 'do-it-from-the-head' methods caused him some exasperation as he repeated the requirements with rhythmic inevitability. I felt dull and uninspired. How to resolve what the landscape was saying with what he was asking for? All I could see was the roundish knoll with the rounded outcrops everywhere plus the roundish, pointed tops of the Wombat Ranges forming a semi-circle around us. Even the river was going round and in the distance, the Brindabellas were doing the same thing. There could be no excavations over one foot in depth because of the damage it would do to the rocky outcrop site. All I could see for the house were round forms like jam tins squeezed into one another and setting off down the hillside in the form of a sickle.

The builderss except for the foreman in charge, would be amateurs without tradition or experience. Superficially the circular proposal appeared complicated, but I believed it would prove otherwise.

There were several advantages in the relatively independent rooms on varying levels. We had to cover a level change of fourteen feet. The stratas could be done one at a time and then fused into each other. Mud brick was the only reasonable material to consider. It is ideal for amateurs who generally do it better than professionals.

The earth was comparatively easy to form in the round with the use of trammels. Windows were marginally more detailed, the roof structure was simple. All roof overhangs were deleted and the facias were wide but thin and wrapped around against the walls. Overhangs were than added at a lower level as verandahs. The roof membrane of malthoid and asphalt-impregnated bitumen with a creek gravel overlay was built up with insulation slabs to control the temperature inside and at the same time, to form a gutter around the circumference of all the roofs. In general, the fascias were opened at appropriate places so that rain water would run from one level to another like a waterfall and find its way into strategically placed and copious semi-circular rainheads.

No doubt there would be variations when construction became reality. That is the sign of a living building. One aspect of this was obtaining a permit from the local council in order to start. John Nicholas and I called at the Engineer's office not knowing what to expect. He had a relaxed Australian appearance about him. He glanced over the plans for three or four minutes, then asked me one or two questions which indicated a good grip of the proposal. He indicated that he was satisfied and made it pretty clear that he felt it would go through without dispute. We could anticipate no troubles in getting a permit. He told us to leave the fees for it there and then.'

The building of the house commenced in 1973. The first foreman I ever had, Rennie Edward, arrived to take charge of the job. In the meantime John Nicholas and I called on Charlie Stevenson, an Eltham man who had invented a mobile mud brick-making machine. He was to go to the site where water and material would be waiting for him, and he would set about making 8000 earth blocks. These were strong because they were made from damp material under great pressure and could be stacked immediately as they were formed.

It was unfortunate that Canberra was enjoying its wettest spring for a generation. Charlie couldn't get going because of the rain. Frustrations set in on both sides. Charlie complained about accommodation and John fretted at the weather. For a few nights the brick makers relieved the tedium by driving the great ten-wheeled transporter, on which the mud brick machine was mounted, into the city of Canberra to go to the pictures. Its mud-caked sides and wheels must have created a strange sight in those clean but deserted streets. The old saying that no mud brick maker likes the rain was very pertinent in this instance and Charlie in common with all mud brickers has only a limited patience.

After making a considerable number of bricks he asked for a further advance which John did not think was due, and differences flared. One day when John was working at the College of Advanced Education Charlie suddenly decided to leave for home. He drove the transporter back and forth over a couple of thousand bricks before he left. John's reaction on discovering the mess was quick, but not quick enough to prevent Charlie getting over the border in the rain. The next day I heard he was back in Eltham.

The promoting of new building methods are always difficult because economic building depends on repetition and organisation, but it is especially complicated when those who make them are pitted against the elements and other unpredictable factors.

On my last visit to Canberra I viewed the completed house late in the afternoon of a wintry day. It had all been fairly well done hut cluttered as the owners had only moved in a couple of weeks before and there were packing cases in several of the rooms. I thought John was showing some signs of wear from the protracted struggle, but his spirit was undaunted as he spoke of wanting plans immediately for some extensions.

Something had gone wrong with the levels of the house which caused the higher stratas to be sunk further into the natural ground level than was intended, but overall it was the most ambitious amateur undertaking to be completed in my experience.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >