We Are What We Stand On, The Coming of the Corporate State

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

The Coming of the Corporate State

Author: Alistair Knox

In the 1950's Eltham began to change from a rural village into an outer suburb of Greater Melbourne. As the metropolis covered nearly 2,000 sq. miles, the phrase 'outer suburb' had different connotations from most other places. When I did a part-time course at the University in Town Planning in 1951-52, I was amazed to discover that Los Angeles was the only other large city with a similar population density to Melbourne. Melbourne then averaged eight persons per acre and Los Angeles, nine.

There was a completely new attitude towards development throughout the world, motivated by war-developed technologies and a universal population explosion. It was beginning to alter almost every concept known to man.

I found the possibilities of Town Planning opened up opportunities to create new types of communications that were dynamic and inspiring. At that period I was even prepared to accept the freeway systems that were beginning to come about in the great American cities-especially Los Angeles. Strangulation by vehicular congestion and grey smog throat were as yet unknown diseases in Australia. The early aids to living ranged from mechanical tools and washing machines to house ownership and a good car for the majority of families. It was enjoyable and gratifying. It revived a sense of well-being after the shortages of the war and the depression which had preceded it. It was only when the inexorable accumulation of these aids began to come between us and separate us as people that the loss of community experience became noticeable ...

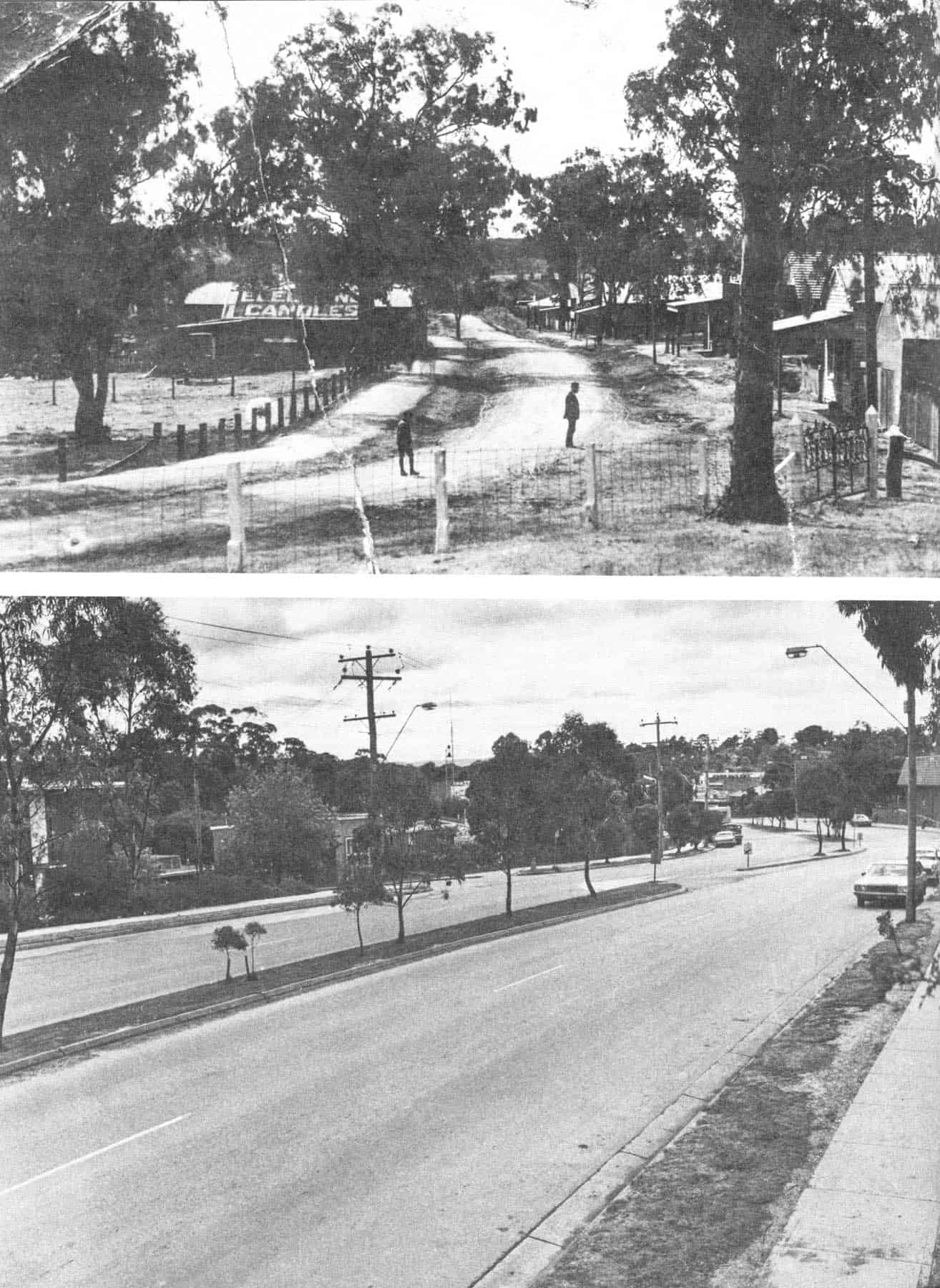

Above top: Before the coming of the Corporate State Main Road Eltham about 1920.

Above bottom: After the coming. Eltham 1980, taken from the same position

Above top: Before the coming of the Corporate State Main Road Eltham about 1920.

Above bottom: After the coming. Eltham 1980, taken from the same position

We were at first hardly aware of the multi-national system that was starting to come into existence, because it was so gradual and reasonable. It was hard to stand aside and observe it objectively. Each succeeding year, however, added to the 'Great Australian Ugliness' that Robin Boyd wrote about and there was apparently no way to stop it. Development was occurring at all levels of our society at an extraordinary rate, both because of natural population increase and the flood of migrants from war-damaged Europe. Nevertheless there remained a general sense of quiet unchangeability as you looked along the streets.

Buildings tended to relate to each other in scale and design. Gardens had neatly-cut lawns, bounded by privet and lambertiana hedges, and European trees dominating the verges of the uncrowded roadways. When Robin Boyd proclaimed what the Great Australian Ugliness was it came as a shock to many Australians. Their eyes had been unable to register the low visual standards they had accepted without question. The first wave of criticism was transferred to the early migrants who started pouring into the country from Europe.

This movement has had a tremendous impact on our insularity. It disturbed us. We had been protected from so much that, in general, we believed the shock waves of Greeks, I talians and other ethnic migrant groups was a phenomenon which would somehow go away. It took nearly twenty years to register that our once conservative Anglo Saxon, royalty-saluting population would have to admit that they had become a multi-racial society. I t was good for us. Most Australians were convinced that there had never been another nation on the face of the earth equal to themselves. They believed that their sporting and athletic powers, relaxed climate and heaV'] drinking habits on the one hand, and the remnants of their middle-class bourgeoise on the other placed them above all other races.

Barry Humphries' new character, Les Patterson is only a slight exaggeration of what existed then and now. His counterpart can be seen in Service and R.S.L.clubs across the country.

I will mention two personal recollections of this type of thinking. The first concerns a barber I heard in an inner suburb in the 40's discussing in general terms with his customer, the son of the local Italian greengrocer. After castigating him in every possible way, basically because he was not Australian born, he concluded by saying, 'Yeah, and he married a white girl too'. The other case was in 1950. John Perceval, Gordon Ford and Alan Green accompanied me to Barham on the Murray River in New South Wales. I had arranged to consult with a lady and her two sons about the building of a mud brick house 25 miles further up the river on a newlyopened rice growing area. Our initial meeting was arranged at the Royal Hotel at 10.30 a.m. on Sunday, after Mass. The temperature was already over 100°F and the bar was comfortably full. I was ushered into a private room and I left my companions in the general bar, spending up my money on a little steady drinking. They all had fair hair and fresh complexions and, as they were unknown to anyone else, they became the objects of attention. They heard themselves being discussed by a group of locals, as if they were unable to understand English. It was automatically assumed they were New Australians and it was agreed they must be Balts, which was pronounced Bolts, because of the colour of their hair and their complexions. The locals were quite surprised when they found that they could answer them back in good Australian.

The Dutch were the most numerous groups of migrants in the Eltham district, probably on account of its hills and valleys. They found it such a contrast to the land they had left. They made excellent settlers. I had a lot of dealings with them and found them highly skilled and hard-working. They certainly contributed greatly to our building developments. Eltham managed to retain its artists, its mud brick builders and its eccentrics because the population increase was slower here than in other parts of Melbourne, and its beautiful natural environment held us with invisible bonds.

The local Council was very conservative. They either did not display a great deal of desire for development or they were unsuccessful in promoting it. Its rocky soil and undulating bushland did not have the same appeal for development as Templestowe and Doncaster did. The diligent German orchardists, who fist pioneered those areas carefully cleared the fields and planted the perimeters with pine trees. To drive from Heidelberg to Warrandyte thirty years ago, gave the impression that the whole of that landscape was marked out in rectangles and squares and geometrically planted with peach trees and pears that covered the quiet hillsides with ordered patterns of pink and white blossom in the springtime. When these areas began to become available for subdivision in the 1950's, it would always cause excitement in the hearts of the Estate Agents as they estimated the dimensions of each rectangle, how many blocks it would make, and how much they would gain from offering it for sale. Eltham, on the other hand, was devoted to resisting the making of roads that formed it into an antidevelopment enclave.

They were the first community movement concerned with environmental survival. Early factors which stimulated it was a common hatred of the Electricity Commission linesmen and their tree-felling operations, whose motto was 'You can't stop progress'. When word would get around that trees were about to be removed, a collection of mud brick workers, university professors, business executives, and hosewives would arrive at the cri tical moment to start a parley. The most accessible Shire Councillor would also be called and the local Engineer would generally issue a stay of operations. It was rather bewildering to those honest toilers who were under the impression they were elected to bring civilization to our backward bushlands.

The post-war economic development expanded throughout the decade in inverse proportion to the quality of our daily lives. Both parents of many households were working and family possessions proliferated. By 1960, material security had been achieved in many cases at the expense of the loss of the family. The particular values of Australian living up to that time were space, freedom, laconic alternatives and economic security. The rapid increase in our financial expectations were too much for us as we began to degenerate into mindless materialism-too many possessions with too little effort.

Eltham was caught in this social decline, but survived because of its ongoing creative living despite the fact that by 1960 many locals were bemoaning the fact that they thought the district was 'finished'. Its mystique and village pattern had largely vanished. For this reason, it is interesting to consider how in 1979 it is still so very different from all other suburbs. Much of it looks just the same as they do, except that the shopping centre is probably a bit worse than most and the houses somewhat more heterogeneous and smaller in the area surrounding the commercial centre. It has few restaurants or places of entertainment. Even the once homely hotel we gathered in had so changed in character none of those who knew it in the early 50's any longer visited it. The continuing life-style has been maintained by the bush and the mud brick building. As these were threatened an intensified struggle emerged to maintain natural living and the development of the whole man. There have been two very distinct periods in the social history of post-war Eltham, the first, with which this narrative is concerned ended around 1960. The second stage is still developing. There are now more suburbanites between the indigenous Community but the offspring of the earlier Society are in many cases better than their parents.

In the early days of low population, limited transport, village-style life and general limitation of money and possessions, there developed a closeknit community that made it quite exceptional because the Eltham environment had drawn them into its misty hills and leafy valleys.

Before the duplicating of the main road through the shopping area and the first street scheme got under way in the 60's, almost evey Eltham road was a narrow pink and yellow clay carriageway with the indigenous stringy bark and yellow boxes crowding onto them from the verges. Until then branches met overhead. Dogwood and bursaria filled in between the trunks of the trees and the wide variety of wattles that mingled with the pungent white blossom of the self-seeded cherry plums every spring caused the valley along the course of the creek to become not strictly indigenous, but these yellow and white blooming periods gave it a special character that was seen nowhere else.

The native birds are today probably in greater abundance than they were then because of the increased tree growth, but they now have to compete against the roar of traffic, which was then much less than it is today. Bellbirds have always been a major accent in the Eltham bush and they are nowhere more appreciated than at the concrete bridge, where the Eltham resident returning from the cacophonous noise of the city is welcomed back into his own territory with their nostalgic, poetic call. Although some thirty years stand between us and the first wonderful flowering of talent and abilitiy these pages have been recalling, it appears only yesterday in the minds of those who experienced it. It two or three of them get together on a street corner or in somebody's home, its only a matter of a few minutes before they are recounting one of the enumerable experiences that made them so diverting, dynamic and special.

We have all grown older, more middle-class and conservative and those uninhibited times of our youth and formative adulthood have been colourful influences on the sort of people we have become. Most of the local characters have died or disappeared. There was Mick, known as 'Metho' Mick, the local drunk, whose girlfriend was Miss Agg whom everyone remembers with a sense of nostalgia and endearment. There was the man who ran across the paddocks in a football guernsey and shorts carrying a bow, with which he shot arrows into the sky.

One who still remains is Nancy Badger the lady with the lawnmower who can still be seen working in Arthur St. and related areas. We were all thrilled when we heard she was to make a trip overseas to England to see the changing of the guard which has been her lifetime ambition.

There was Keith 'King' Lear, the Hairdresser, who had a barber shop when there were only about half-a-dozen shops in Eltham. He is a lovely character who was prepared to drop his scissors at any time for any reason. When you went for a haircut there were always pauses for the laying on of bets which he would want to make and a little drink around the corner before he started his tonsorial activities. His styles were not perhaps of the standard of John Todaro's 'Guys & Dolls' where we go today, but it was all part of how we lived and moved and had our being.

Peter Glass tells an interesting story of going down to 'King' Lear's one hot day, realizing that it would take some time to have a haircut, but not realizing in this instance just how long. It took a week! After the usual laying of bets and a little drink, the hair-dressing proceeded. Peter had had one half of his hair cut when the fire bell went. Within a second, 'King' Lear had run out of the shop to join that happy band of Country Fire Authority volunteers who are still the official quenchers of fire in the Eltham district, shouting 'come back and I'll finish it next week'. In the meantime, the usually immaculate Peter Glass would have to wait in a dishevelled state until the weather changed, the fire danger dropped, and life returned to normal.

Another local identity was Garnie Burgess, marine dealer and general carrier. For some time he had a secondhand yard next to Staff's, whose old grocery on the Main Road was removed when the road was widened. Garnie left Eltham for some years after this episode. When he returned, he found a sign stretching overhead across the Main Road saying 'Welcome back, Sir Garnet'. 'King' Lear was also the instigator of this activity. The list of anecdotes covering all sections of our society was endless because of its closeknit nature which allowed everyone to know what everyone else was doing. Longevity has been rather a feature of those who enjoyed those relaxed days although there were one or two notable deaths. It is impossible to forget Pauline Ford, who died so tragically in the 60's. She was a most unusual and capable woman, whose ideas were far ahead of her time. It was not until twenty years later that many of her ideas, ways of living, and design of clothes and social attitudes became the order of the day. Sometimes she drank a little more than was good for her and there were occasions when she would babysit for a friend for a night and on their return she would say, 'I don't really want any money for babysitting, I made a couple of 'phone calls'. The trouble was that the 'phone calls she made could be to someone who lived in Hawaii or the United States. But no matter how cross you could get for a moment with Pauline, her spontaneous laugh and ability to apologise the morning after for what she had done the night before were inimitable, and evidence of a boundless spirit and exciting personality.

Distance lends enchantment and, no doubt, we remember the good and forget the bad.

If one had to choose a particular time and designate it 'The Golden Age' , it would be between the years between 1946 and 1950. It was a place of uninhibited laughter from morning till night. We had little money and fewer cares and believed we were standing at the dawn of the golden day. Some did not realize it was already there until it had passed and was too late to recall.

Perhaps it was the nights that produced the greatest impact. The combined effect of the listening silence in the moonlight as it shone on the trunks of the candle-barks would sometimes cause the magpies to sing muted carols in their nests the whole night. When the autumn mists fill the valley, the combined scent of wattle and eucalypt would produce hypnotic illusions that touched the sense of eternity that rests deep in the heart of every man. Everyone understood these experiences. All who remain acknowledge them. Alan Marshall had the last word when he said, 'People did not make Eltham, Eltham made people'.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >