We Are What We Stand On, The Dunmoochin Episode

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

The Dunmoochin Episode

Author: Alistair Knox

Few would dispute that Clifton Pugh has been one of Eltham's best artists ever since he established himself as a member of its creative community when he built at Cottles Bridge in 1951.

He was a little later arriving on the painting scene than Sid Nolan, Arthur Boyd, John Perceval, Bert Tucker, Danila Vassilief and the other immediate post-war painters who had achieved international reputation by the middle 50's while he was still gaining general recognition. He has, however, continued to grow in stature both as a landscape and portrait painter right up to the present time.

When I called to see him recently to discuss his Eltham experiences, I was reminded everywhere I looked of the long and varied associations we had shared over the years. The original one-roomed shelter he first erected had grown into a large rambling studio house. Every wall was crowded with paintings, every corner occupied with sculptings, Sepik River carvings, a human skeleton, the skeletons of native animals and other paraphernalia that had been part of his varied interests over nearly thirty years.

I first met Clif before 1950, shortly after he had been discharged from the Australian Army of Occupation in Japan, where he had gained the reputation of being a fighting soldier in the field and an explosive one off it.

He had been a pupil of Sir William Dargie, whose realistic approach was reflected in the remarkable painting facility Clif displayed in his early work. He shared a studio in a barn behind a property in Royal Parade with Kevin Meynell a romantic young painter who also went to live at Dunmoochin. Above the entrance was lettered a large sign of three words which said 'Live, Love and Paint'. A considerable quantity of these activities took place in and around that locality in those dynamic post-war beginnings.

I always found Clif a great friend. On more than one occasion he stood between me and an antagonistic type who threatened to thump me for some of the outlandish words that used to flow from my mouth in those provocative years.

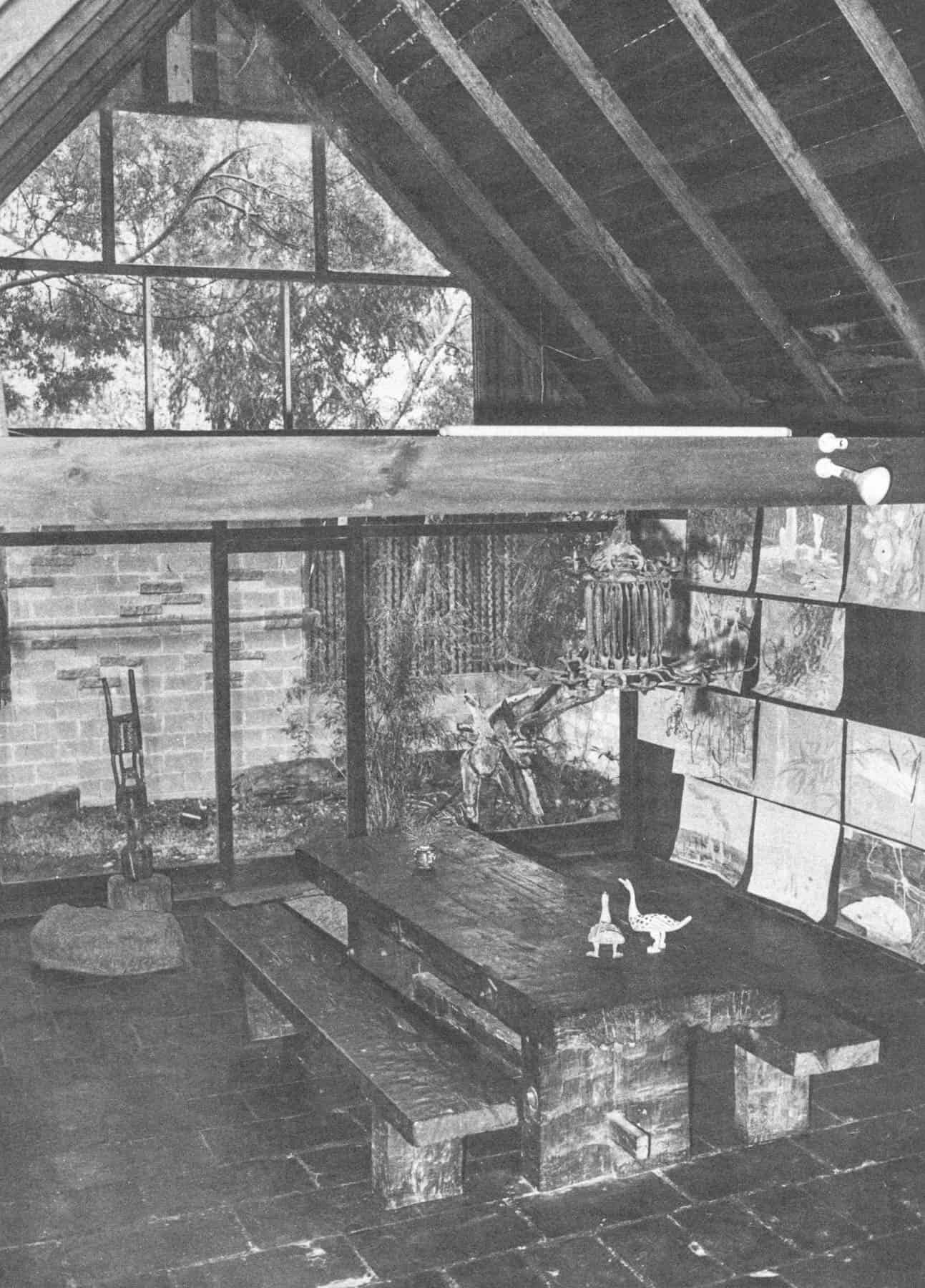

An interior view of Clifton Pugh's studio home

An interior view of Clifton Pugh's studio home

I was delighted, therefore, when Clif phoned one day in 1951 and asked me if I had any older timber I was prepared to sell cheaply. It occurred when I was concluding my first building development comprising four substantial houses on a 20 acre orchard in Templestowe. My clients consisted of five women and one man engaged in one of Melbourne's earliest common developments. It was, in reality, a strong female enclave. The girls were mature women art students, and when I mentioned Clifs request to them, they were thrilled to supply him with the discarded timber we had stacked on site.

Building was still very difficult due to post-war shortage of quality material, and, as a consequence, there was generally a fair quantity of unuseable timber left over. They were pleased to be able to assist a struggling fellow painter to build a shelter for himself. We negotiated to take a large overflowing load of scrappy-looking scantling to his land at Cottles 'Bridge for £3 in my Matador truck. It was a fine, brisk spring morning when we set out and there was a sense of adventure in the air. As we approached Cottles Bridge, the small white clouds were hurrying across the bright blue sky in an everchanging backdrop behind the broad billowy hills that divide the Diamond Creek and the Arthur's Creek valleys. They were heavily timbered and little changed from the beginning of time. As we drove carefully up the slope from Cottles Bridge, Clif said, 'This is where I am building', indicating a point on the side of the road with a sense of certainty that I couldn't understand.

There was no apparent distinguishing mark on that particular site that separated it from any other on that hungry-looking sunny landscape. After we deposited the timber and set off for home, Clif told me how he bought the land. He explained that he had come to the realization that he had to get out of the city. His search began at Cape Woolamai, Phillip Island, which to his later relief did not eventuate.

He then went with Joe Hannan, the artist, to bid for some land at an auction at Hurstbridge, which proved too expensive. Finally, he came on his land at Cottles Bridge by chance. He used to catch the train from Hurstbridge and then start walking and looking. He approached the Belotswho were the people from whom he eventually purchased the land-from the rear of their property when they were feeding their fowls. He tried to persuade them to sell. By the third week they had almost been driven to distraction as he followed them around like a persistent spaniel.

They had never struck anyone like him. They were partly fascinated, because he was an artist and partly annoyed, because he wouldn't go away. Suddenly they said: 'All right, you can have the whole lot for £5 an acre!' It was only then he realised he just could not pay for any of it. He was on the dole and there were 200 acres available. Our whole attitude to money was then very different from what it is today. Objects we desired cost comparatively little, but we had practically nothing with which to buy them. Clif was a determined man, however, and he finally arranged for Alma Shanahan, who was a school teacher and therefore comparatively rich, because of her permanent job, to purchase 2 1/2 acres.

Myra Skipper, Matcham's wife, had also been left £200 a little earlier and she purchased two acres. Clif contrived to obtain six acres for himself through an agreement with the Belots to pay for it by working for them.

He continued to accumulate more and more sections of the land at varying prices from time to time until he eventually owned the whole of it. The Belots proved very helpful in their attitude in those early days when, as Clif pointed out, £5 an acre was a lot for a man on the dole. They became sorry later on because it became much more valuable through the introduction of trace elements and other soil developments that made it more productive.

Clif began his first building at Cottles Bridge in September 1951 on the famous day that Mr. Menzies lost the 'Yes/No' vote to outlaw the Communist Party. Clif immediately commenced work on a wattle and daub construction of one room in the manner he had observed the early settlers had employed in the district in the pioneering past.

He cut down some stringy bark saplings and placed them in the ground in a line, three feet apart. He set a few pieces of scantling over the pitching plates fixed to the top of them and lined them with the 6" xl" he had obtained from me. The roof cover consisted of one layer of malthoid fixed to the decking with clouts. Wattle and eucalypt branches averaging between one and two inches thick were next nailed horizontally between the sapling verticals at close intervals.

The first real problem occurred when it came to rendering them with mud, because there was no water available. Alma Shanahan, who had started coming up on week-ends to make bricks for her own house, was working with Clif when this dilemma occurred.

Even as they were wondering what to do, a good rain set in and the dusty clay soil surrounding the building was quickly wet down and turned into an ideal render to seal the walls. They rushed outside and snatched it up in handfuls and quickly started plastering. No sooner had they finished than a drying wind started to set it hard.

No building could have been simpler, cheaper or quicker to erect. There was a door for an entrance, a second-hand window which cost a few shillings at the wreckers, to look out of and a mud brick chimney to supply cooking and warmth. The floor was of earth and the main decorations were a couple of old flintlocks and a bow and arrow hanging over the fireplace.

It had never occurred to Clif to apply for a building permit in those secret, carefree days. We may have had little money, but we were also wonderfully free from bureaucratic controls. We appeared insignificant in the international art scene at that time, but that would change. Men like Clif had immortal longings in them which would soon make them part of our national heritage.

There were few post-war shortages in 1951 more aggravating than the absence of telephones. It was quite common to wait for periods up to two or three years to obtain one of those modern torture machines. Some women would become pregnant in order to get a priority for one, but in Clifs case it fell out of the sky like a miracle.

He was working on the frame of his wattle and daub hut when a P.M.G. mechanic came over the hill and asked him if he wanted the telephone installed. Clifwas so taken aback, he said: 'I do, but I haven't anywhere to put it'. His obliging mechanic said: 'Never mind. I'll bring over a handset tomorrow and you can put it in the fork of a tree and we'll throw a bag over it. They are trying to set up an exchange at Arthur's Creek and they need 30 subscribers. They have 29 and you will make the thirtieth'.

I knew nothing of these incidents until I heard Clifs voice on the phone about four weeks after I had carted up his load of timber. He said: 'I've built that house AI, and I've got the phone on too!' I was so surprised that I had to get up there quickly to see it all.

When Margot and I arrived at the site, Clif could be seen in the dark, smoky interior wearing a strongman's leopard skin uniform and sandals. He had a really good figure and the 'noble savage' costume suited him very well.

We were even more surprised by the building than by his appearance.

When he bunked us up on to the roof to look at his handiwork, the whole structure seemed to sag under our weight and we thought we were going right through.

Clif told me that he later gave up his leopard skin and bow and arrow, which was also accompanied by a leopard skin quiver full of arrows, for two reasons. The first was that he was unable to hit anything and the second was that when he was out hunting one day he suddenly came across two men armed with shot guns. As soon as they caught sight of him, they turned and fled in dismay and were never seen again in the vicinity. I suppose he felt a little too closely identified with Buckley, the wild white man, for comfort.

When Alma Shanahan made her mud bricks in the valley nearby, Clif had what he described as an off and on relationship with her. He bought a horse and cart to help haul her bricks from the valley on to the building site. It was inevitable that this method of transport should prove as useless as most of contemporary man's attempts to return to the simple lifestyle do. It is a source of wonder how they got so much done in the pioneering days!

Clif met Marlene at a Vic. Art's party that year and two weeks later she was living with him at Dunmoochin. Then she became pregnant and Clif had to build even faster than he had at first. This family unit brought more people to the embryonic community as the artistic dream time dissolved in the economic struggle.

Gilbert Hicks was one who joined the Dunmoochin community in 1955.

He was a businessman from Western Australia who set about organizing them. They formed the Dunmoochin Artists' Society and they all owned the land in common. There were thirteen articles in the Constitution and all of

them dealt in some way with environmental problems without the members being consciously aware of it. They have become a strong branch of the Eltham socio-artistic community that has instinctively understood the direction that creative lifestyle would adopt. The dry bush and the little bouncing hills with their mists and moods will continue to have an effect on Eltham people forever.

The Dunmoochin landscape is the highest point for several miles that produces a sense of elation as you can see out in all directions; Melbourne to the South, the Kinglake Ranges to the North, Whittlesea to the West and the Dandenongs to the East. It provides an instant panorama of the geographic history of the whole of Melbourne and its environs. It reminds the local inhabitants how privileged they are to be part of it.

Dunmoochin had its early growing pains, but after it settled down there have been remarkably few changes and the personnel remains much as it originally was. One of the rules required was that no house could be built in sight of another, which meant that those who occupied it initially provided nearly the maximum population density for all time. The fact that Dunmoochin is the oldest surviving community in Australia is a silent witness to its importance to the City of Melbourne.

Economics had a lot to do with the social structure of Eltham. It was the cheap land that attracted many of the individualists. In the fifties those who were leaving the city or who were concerned with its cost of living were creating their own environment. There was no water supply or electricity and in many ways they were close to pioneering conditions. Adjacent municipalities, such as Doncaster and Templestowe, were claiming they were the 'Toorak of tomorrow'. Suburban Melbourne matrons winced slightly when they had to mention the word 'Eltham'. Its non-conformiSt character was a threat to their sickly-sweet security. That has completely changed in the present decade. They have now turned covetous eyes on its straggling landscapes and represent a threat to its continuance as a place for free spirits. Their children attend its fashionable schools and they are doing everything in their power to reduce its unique quality into a second-rate suburbia. May they never succeed!

As Clif mused over his beginnings at Dunmoochin, he recalled some of the colourful identities who formed it. There was Larry Stevens, who always had his own strip of thirty acres nearby, who was an emotional part of it-a father figure. Although he never actually owned any of the community land, he always appeared to take part in the community meetings they held. John Perceval bought five acres, which he later gave to Neil Douglas who never got to live there either.

Clif believed that Matcham Skipper, who lived in a studio behind the Russell St. Police Station at that time, was the source of the drive of 'things artistic'; Tim Burstall, the drive of 'things social'. He felt he owed Matchama great deal by causing him to understand that art is for art and not for profit.

Matcham was leading the artist's life which Clif emulated. Clif said it cost him, amongst other things, his first wife, June, who couldn't take it. She went off to live in Penang. He also considered that Matcham was much more the real influence on the younger people of Eltham than his master, Justus Jorgensen. There was a new sense of artistic upsurge and zeal in the fifties, a time of commitment and total dedication that is now no longer there. 'Today', Clifsaid, 'they do art at the Institute of Technology and when they come out they get a job and paint on the side'. When I interviewed Larry Stevens, I became aware of Clifs dedication at all costs to his painting and how it caused him to establish his career.

I had employed Larry Stevens in my very early mud brick experiences a few years earlier. He had a fairly cavalier attitude to working for wages, similar to many other Returned Servicemen. His laconic approach to life concealed a dry sense of humour, he was rather given to nostalgic dreaming about ways to earning an easy living. They generally related to tropical climates and places like the Great Barrier Reef. He once explained to me how he hoped to make money by beachcombing in Queensland. That State was more remote in those days and he was convinced that there would be a lot of fossils, which he Americanized into 'farsils', waiting to be picked up and sold to scientific 'geezers' from the States. Australians in the immediate post-war years regarded all Americans as Yanks; rich, gullible and exploitable. He eventually made his dream journey to the Sunshine State to find that beachcombing was better to be contemplated than to be part of, so he returned and settled in Dunmoochin country.

It was at this period that he gained an admiration for Clif and his great determination to paint despite all levels of poverty. He recalled how he and another painter, Joe Hannan would set off in an antedulivian BSA motor bike with a coffin-like box for a sidecar on painting excursions along the Yarra Boulevard. He believed Clif was a tremendous idealist and thought that part of his poor shooting at rabbits was because he did not really like killing them, although they swarmed around him in millions. Larry's voice took on a dramatic tone when he described their abundance: 'The whole landscape seemed to be a seething mass of them, heaving and moving like a brown carpet. Their eyes would reflect in the light we carried as we walked across the paddock at night'.

Larry referred to Alma Shanahan, who was also there, by saying, 'Alma could work like a bloody horse'. 'She built her own house practically singlehanded, despite the fact that she did not know how to use a straight edge. One of her walls curved right outwards at the top, but it made no difference to her'. He also believed that Clifwas subject to Walter Mitty phases in the early days. His bow and arrow period, which at one time was accompanied by a Daniel Boone cap, made from some pieces of sealskin, he obtained from some odd source was a Robin Hood act.

Matcham Skipper who weaved in and out of Eltham post-war history and was a continual source of inspiration, also had a reputation for being farsighted and very mischievous. At one stage, he traded Clif and Larry a thoroughbred Saanen goat for an electric record player. The goat was reputed to be valuable but after several attempts to get it into kid proved fruitless, they felt that Matcham may have known that it was sterile when he traded it, but little was to be said. They placed it in the 'unpredictable' basket that exists between natural friends and let it lie there until it became the source of a joke that was to eventually develop a deeper sense of union between them. Whatever the goat's lack of kid-bearing capacities, it manifested all the other characteristics that make most normal people treat all goats like lepers. Its reign of torment lasted for about two years. Larry recalls how he was leading it in a hailstorm one day when it got away from him and bolted into their house and jumped onto their bed. His wife, Hope, was pregnant and unable to cope with it, but that did not seem as serious as when it ate the neighbours prize gladioli bulbs. Those unctuous exotic 'blooms' were enjoying their pre-Barry Humphries popularity. Such scandalous destruction by the goat made it clear that its life would need to be shortened. I ts final act was to leap up onto the mud brick chimney that Larry had very slowly and labouriously raised to about six feet in height. As the bricks had become wet with the long rainy period, they crumbled under this assault and fell to the ground. This unspeakably blasphemous act forced Larry to lead it out to execution. He tied it to a tree and gave it a stick of celery for compassionate reasons, then shot it. He was so filled with remorse that he just turned away and left it to nature to do the rest in that unfrequented spot. A considerable time later, one of Marlene Pugh's friends came across it in a half-decomposed state with the rope still around its neck and started a rumour that Larry had strangled it.

Hope and Larry's house consisted of two rooms, each about 20' x 12'.

When Hope came back with their new baby daughter, Mandy, its earth floor had been paved with some stone slabs from the nearby creek. The building had a good front door, but they could not afford internal ones. A neighbour, Billy Deagan, erected a sack across the opening between the rooms as a substitute. it was beautifully marked in Chinese characters and in the middle of these oriental hygroglyphics was lettered in bold English printing, 'The House of Happiness'. It so impressed Billy that he called his own wattle and daub shack in the nearby gully 'The House of Happiness' also.

During the six years that Larry and Hope lived at Dunmoochin, they saw two or three families try to make a living on the next door farm that later belonged to Mike Calder, but in each instance they went 'broke'. The last to leave had kept a few pigs whose presence generated fleas. Larry's voice trembled with intense feeling as he recalled, 'It was bloody frightening'. 'We wrote to the Department of Agriculture, who informed us about the life cycle of the flea'. Larry's voice took on the Humphrey Bogart accent he used in 'The Petrified Forest': 'If a male doesn't get a feed of blood, it remains

infertile, but the female can still lay eggs-millions of them, and all of them males. When one of them is lucky enough to get a feed of blood, be becomes potent and the cycle is renewed. The fleas seem to cover several thousand acres'. Larry uttered the words 'a feed of blood' in such sepulchral terms, it gave the impression there were dams full of it everywhere.

He would explain how he went out to work and later returned with his overalls coloured black by them. Larry was a superb raconteur. 'Hope and Carlos-did you know Carlos? Ate like a horse-a big outgoing fellowexpressed himself well. He would click his fingers or click his tongue when he wanted to make a point. He played some endless card game with Hope and they had competitions to see how many fleas they could catch in an hour. We all wore out a lot of clothes scratching them'.

'Clifs house still had an earth floor and he had spread bullrushes over it and the fleas got into them as well. It was bloody frightening' , he concluded with feeling.

Clif painted Larry and Hope in their house and called it 'The Chicken Farmers'. Larry and Hope were carrying buckets and their two little kids were in it also. 'It was a marvellous painting', Larry continued, 'and I bought it for six bags of foul manure worth 10 /6d. a bag'. It was done just as Clif was emerging from his student period into his real style. 'I very reluctantly had to sell it later for £600. I rang Clifto see ifhe minded. Parting with it was a major regret of my life'. I recollect having seen the painting once or twice and the memory of it still lingers in my mind. It's rather Drysdale subject matter, combined with Clifs close struggling association with the Cottles Bridge landscape, expressed a heartfelt appreciation of the beginnings of Dunmoochin in a way that nothing else could 'Clif has become much softer over the years', Larry concluded, as he gazed out of the shop front of his picture framing business in Carlton. 'He often calls in for a chat and a joke about the old times'.

Larry has changed very little over more than 30 years. He still resembles the poor man's Humphrey Bogart. When I saw him come out of a country cottage with a shot gun to warn some people off his property in a bit-part in Tim Burstall's film 'Stork', I thought it was 'Bogey' himself.

Tim Burstall had a wide selection of Eltham characters to call on in his early film-making period, which some of us still remember with great nostalgia. It was the beginning of the 'non-city lifestyle', a retreat from suburbia, which has some twenty years later become a major cause in Sydney's population dropping over 26,000 in the year 1977 and Melbourne's reaching a zero increase population growth, despite the fact that Greater Melbourne itself covers 1,950 sq. miles and Dunmoochin in technically part of it. They put up with the rabbits, the fleas, lack of water and the like for the opportunity to develop an indigenous community. No-one who has ever tasted the liberty it offers and compared it with the pressurized citysuburban life appears willing to exchange it. Its primitive beginnings have quietly become less arduous with the evolving years. Its members are now acknowledged artists in their own right. Clif believes much of the credit for the initial idea to get the community going was due to Frank Werther, who is also a painter, who built close to Clifs. He caught this community vision from the Eureka Club which he used to attend when he first came to Australia. There was a strong social democratic spirit abroad before much of Melbourne's population had been seduced by the money and suburban comfort of Dame Edna Everage and Sandy Stones.

The attempts of the Dunmoochin community to be self-supporting from the land were never successful. They had first decided to keep a cow and fenced off a small paddock on which to graze it. 'Thank goodness', said Clif with deep feeling. 'We gave up that idea before they were able to get a suitable animal'. The Dunmoochin community land is now a refuge for up to twenty-five kangaroos. The next project was an otchard. As the rabbits were still in plague proportions, it was necessary to fence the land in order to plant it out. They could not afford new netting, so they raided the local tip and bought back secondhand material which they enthusiastically mended between them. But it was of no use. The rabbits found a way of getting in and only one tree survived. This still stands today, the solitary witness of a lost environmental cause. The community then decided that a pine plantation was the way to make the land earn money. The pine tree was not at that stage the anathema of the Australian landscapers. Only Marlene Pugh comprehended what a disaster such a course would be to Dunmoochin and its relationship with the bush. She understood it before the visual painters did. The rabbits came to her aid in this instance and ate some of the trees, then she settled the whole argument by pulling the rest of them out of the 'ground.

The Constitution of the Dunmoochin community required a unanimous vote if anything was to be changed, which in effect meant that nothing ever was. Clif said, 'On reflection, this condition probably did more for its survival than any other thing.'

The early community's common ownership of land ran into difficulties because of Clif and Marlene's children, Shane and Dylan. They were the only ones there at that time. The others did not intend to have children and there was a fear that they would eventually take over the community.

The dream of community ownership rested with the men. The women sought the security of private ownership. Among those who have lived there at different times were Kevin Nolan, the Sculptor/Engraver and his wife; Frank Werther and Lea; Myra Gould and Alma Shanahan. Kevin Meynell also lived there until he was killed in a car accident in the late 50's. John Howley, Don Laycock, Mirka More and Laurie Dawes, John Olsen and Frank Hodgkinson were also members. They were all name painters, some of whom are famous. There was also the architect, Maurie Shaw, who built a most remarkable house for Leon Saper. Frank Dalby Davison, the writer, and his wife Marie had lived nearby on a small farm since the 1930's. Frank died some years ago, but Marie still carries on the property, which has been most appropriately called 'Folding Hills', on her own. She has an elegance and charm that sets her apart from every other Dunmoochin inhabitant.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >