We Are What We Stand On, The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

Author: Alistair Knox

The major contribution of Tim Burstall to the Eltham community in the 1950's was the making of the first film by Eltham Film Productions. The decision to make the film 'The Prize' took place at the end of 1957 when Betty and Tim decided to forgo spending the £200 they had borrowed to build a septic tank and put the money towards an attempt to make an Australian film of quality. This was an element totally missing in the otherwise expanding aesthetic, social and intellectual qualities of the period.

It started on January 2, 1958. I don't suppose even Tim thought at the time that it would be the first day of the renaissance of the Australian film industry.

Realising what has happened on a national and international scale in film production since that time causes the realisation that it was almost inevitable that the movement should have begun in Eltham, It was just one more example of the buoyant confidence generated by a great deal of natural talent in the district which caused it to surmount technical difficulties and proceed into unknown places without finance or experience. There had always been a sense in which we helped each other in any new project.

Matcham Skipper, the sculptor, had been urged for a considerable time to go into full-time sculpture. He had a remarkable ability in this field, but he explained that he would need to have a big jewellery exhibition first in order to give him some capital reserves. So ten people arranged to pool £400 between them, which was actually a sensible sum of money at that period with which to purchase silver, gold and semi-precious stones for the work.

The exhibition was held at Brummels in South Yarra and came off as expected, except that Matcham did not go into full-time sculpture. It was a great pity. While he had the ability to do almost anything better than almost anyone else, and he had created a new standard of art jewellery over the years, it would prove an easy medium to copy and it only used up part of his remarkable talents and techniques. His friends still believe he could have made an international mark ifhe had stuck mainly to sculpture. Some are still waiting for it to happen!

A young Belgian photographer who looked very French, named Gerard Vandenberg, had become friendly with the Eltham group. He earned some money by taking studies of their children at £5 a time and making them look very 'Left Bank'. When he heard there was a possibility of a film,

he was very anxious to become the cameraman. We had some doubts about allowing this, because we had no real evidence of his experience, but he finally became firmly entrenched in the film unit.

Tim Burstall, who was a public servant at the Antarctic Division, wrote the script at work; Dr Freddie Jacka, who lived next door, was the physicist at the same Department and he procured the camera that Sir Hubert Wilkins took to the Antarctic in 1930. They found it was impossible to use because it had no rangefinder and the distances had to be measured by tape.

A camera was then hired from a film company in East Melbourne, which was to be used to make the whole film. There were many traumatic scenes at the studio when we went to see the rushes. When the scenes flashed onto the screen vertical white lines would sometimes occur in the image. This indicated that the negative had been damaged and the whole of the work was rendered useless.

The photography itself was often magically beautiful, and, as we saw our cherished activities had been condemned through technical faults, we raged at the camera, the Cinematic Company we were dealing with, and everyone else and everything else except ourselves. We had deputations to the directors arguing that it was their carelessness that was sending us insolvent, but it was all to no avail. We needed them. They were the only people at the time we could use. We remained uneasy bedfellows for more than a year until we got to the cutting stage, which we did in Sydney. It was a strange film crew. We would arrive from the four corners of Eltham at a given point at a given time. Places like the Brougham Street bridge over the Diamond Creek, the Yarra at Morrison's and the Bend of Islands were common locations. We would just step out of our cars and start shooting. Eltham was much quieter in 1958. There was no industrial area to speak about, and practically no houses visible up and down the creek from Brougham Street bridge. The paddocks in springtime were a combination of river wattle and cherry plum blossom hedge-rows, that still felt and smelt like an unbroken country scene.

The actors included Dan and Tom Burstall, who were then eight and six respectively, Marcus Skipper, who was seven, and Cyril Jacka's daughter Liza the beautiful little heroine of much the same age. Matcham Skipper, the rabbiter, and Siddie Webster, the sideshow man, were the only adults in the cast. Siddy was regarded as a somewhat gypsy-like figure who later surprised us all by marrying a rich lady and disappearing from our society forever.

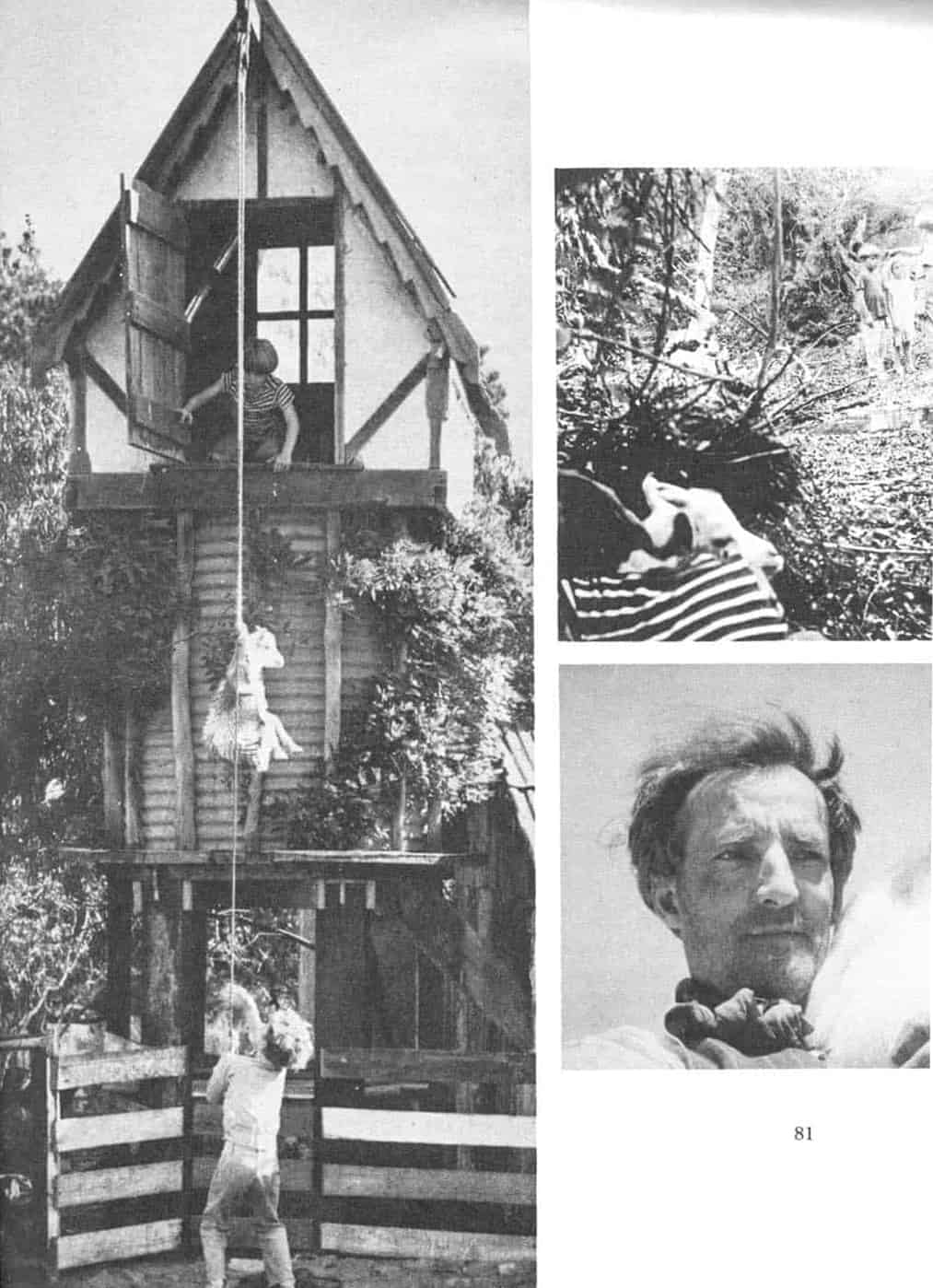

Scenes from 'The Prize': Left: Dan Burstall and Marcus Skipper hiding the goat.

Right top: Dan Burstall misdirecting Tom and Lisa while Marcus hides goat in the foreground.

right bottom: Siddy Webster the side-show man

Scenes from 'The Prize': Left: Dan Burstall and Marcus Skipper hiding the goat.

Right top: Dan Burstall misdirecting Tom and Lisa while Marcus hides goat in the foreground.

right bottom: Siddy Webster the side-show man

A considerable part of the script concerned sideshows and we shot our first major outdoor scenes at the Korumburra Show. We found ourselves in a sort of country isolationism. Some people began demanding appearance money and others thought we were shooting scenes of cruelty at the rodeo. At times it became rather tense. It didn't take me long to realise that taking a secondary part in films was not my vocation in life.

Matcham, as usual, performed well both in acting and advising Tim, who was not always as receptive as he could have been. One of the technical successes of the film were the tracking shots that took place over the paddocks and in the Lower Park. They were all done from the roof and the front bumper bars of my Volkswagen sedan.

Shooting scenes in 'The Prize' from the Volkswagen sometimes meant that four people had to combine to hold the camera and virtually blind my vision. We would set off at greater danger to life and limb following the fleet footed Liza as she sped through the long dry grass in the red-gold afternoon.

On other occasions, there were equally dangerous river scenes. Tom Burstall could scarcely swim, and as he, Dan and Marcus had to shoot the fast Bend of Islands current in barrels, great care had to be taken to prevent a tragedy.

It was usually Betty Burstall who was in charge of this aspect of affairs.

She would lie up to her nose in the rapids for nearly a whole afternoon waiting for Tom to crash over them in his half barrel and fall out into the deep water.

Gerard, the cameraman, had more enthusiasm than natural bravery and when he had to hang out over the stream, he didn't want to go. We had to goad from behind as we encouraged him up three bendy saplings we had tied together that hung over the water. This precarious elevated device gave him a really unparalleled shooting position, There were many other beautiful scenes, particularly the hide and seek sequence at Montsalvat, and the ride through the bush on which Tim the rabbiter took Tom. They drove along the beautiful unmade roads of the district to the accompaniment of Dorian Le Gallienne's music. Dorian was for many years a resident of Eltham who lived with Dick Downing in Yarra Braes Road, He is still considered by many to be the greatest composer this country has produced. The music for 'The Prize' in its own way was no exception and it demonstrated his marvellous ability to capture the spirit of what the eye was seeing.

The film itself ran for over an hour. It had a most poetic quality, particularly in the way it was undergirded by the musical score. It did not take long for Tim's £200 to run out, together with the £100 I contributed.

The rushes were viewed by Colin Bennett, the film critic, who wrote: 'Only £1,000 required to produce the best Australian film since the war.' Finally, Pat Ryan, who was a somewhat Bohemian nephew of Lord and Lady Casey, supplied the money and became the producer. He and Tim took

it to the Cannes Film Festival, where it won a Bronze Medallion, but it was not sold for commercial distribution.

Tim was to find it would be a long hard road before he received distribution rights for his films. Oddly enough, when he did, the film that established him financially was' Alvin Purple', which was a long way from the artistic character of film-making he started off to achieve.

This is an appropriate time to record the film directing and work of David Baker, who lives in North Warrandyte. He is fully professional and a man of many years experience in the field. He and Tim are Eltham's major film directors, if one neglects Philip Adams, who also has an Eltham connection.

David's most important film was 'The Great McCarthy,' which ran in Melbourne four years ago, but he also did many television and shorter films including 'Squeaker's Mate.'

'Squeaker's Mate' was an excellent film that finally reached the commercial screen at the Camberwell Theatre as a support to a Bergman production. It was taken off because some patrons thought it was too violent. It was based on a story by Barbara Baynton, a promising Australian writer of the turn of the century.

The female lead in the film was taken by Myra Skipper, Matcham's wife. She performed brilliantly and it is sad that a few middle-class suburbanites objecting to the picture may have caused it to be lost to the future.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >