We Are What We Stand On, The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Author: Alistair Knox

At this time post war Australia was pregnant with possibility and challenge. The country was enjoying an international 'high', partly due to its newfound capacities, partly because the continent of Europe and sections of Asia were groaning from the results of war. Elsewhere, Israel and Pakistan had become independent states and China had adopted a Communist form of government. For this reason, I will recount the strand forming the Murphy's Creek Homestead episode first because it was an unusual Eltham highlight in this colourful period of the new Australian society. It can be safely stated that the 20th Century never dawned on that faraway place in the centre of Victoria called Murphy's Creek, despite the fact that little more than 100 years earlier the same district was among the most romantic places in the whole world.

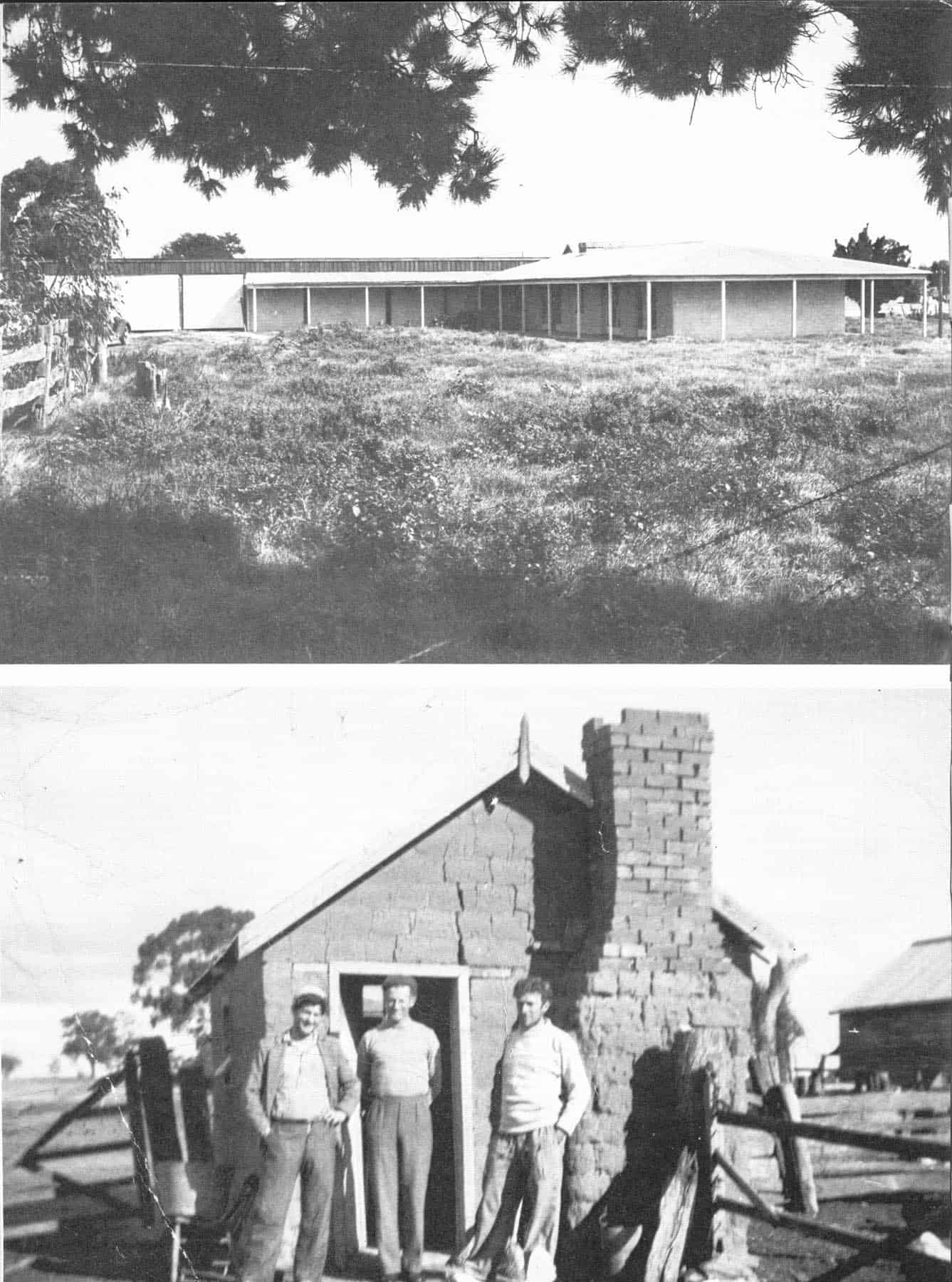

Above top: The Tarnagulla house.

Above bottom: The ill-fated first contingent - L to R Cyril Jacka, Neil Douglas, Gordon Ford - who made 5,000 unusable mud bricks

Above top: The Tarnagulla house.

Above bottom: The ill-fated first contingent - L to R Cyril Jacka, Neil Douglas, Gordon Ford - who made 5,000 unusable mud bricks

It was a midway point in the Dunolly ITarnagullal Moliagul triangle, the centre of the fabulous alluvial goldfields north of Bendigo. Many great nuggets were found within a few inches of the surface, culminating in the 'Welcome Stranger' at Moliagul, which was the biggest piece of gold ever discovered in the world. At Tarnagulla, the Commercial Bank had been the last office to close its doors just before we commenced building at Murphy's Creek, four miles away. It was one of the six original banks, which were lined up betweeen stores, saddlery shops, barber's shops and the 13 hotels that were part of that historic town.

An unusual element in the make-up of this Commercial Bank was the tall factory chimney located in one corner of it. It was connected with a furnace that smelted the nuggets into ingots, preparatory to sending them down to Melbourne under escort. Although an almost eerie quietness now reigns where once there was so much bustle and activity, the Eltham men who came to Tarnagulla to build the Nicholls mud brick homestead were in every way as colourful as the early gold-miners had been.

The first contingent comprised Gordon Ford, Cyril Jacka and Neil Douglas. This trio had been drawn to the settlement in the hope of making a great number of mud bricks in a very short time. It was a commercial enterprise. At one shilling a brick, it represented a small fortune. It was to eventuate that their first attempt to introduce mud brick buildings to the area would not be a success. The site chosen to make them was where some pigs once used to wallow in a series of holes about two feet deep in a paddock behind the heterogeneous collection of buildings that comprised the farm and its surroundings. There was a large cluttered machine shed with ancient harness hanging on the wall; there were some old fowl pens, an apple house, a dairy, a small mud brick shearer's quarters and a large shearing shed surrounded by sheep pens. In order to make the bricks, it was proposed to follow the early Eltham system of breaking back the topsoil into the pig holes, in which there was some water; and mixing it by foot as the work proceeded. The pugged material was then to be barrowed out and moulded into bricks nearby.

The first time I saw the Tarnagulla site was a cold, windy day and the overall feeling it registered was one of melancholy and of struggle of man against the immutable forces of nature. The dominating feature in the landscape was Mt. Moliagul, about four miles to the North. Its granite silhouette, reminiscent of a sleeping lion, gave mute evidence of the antiquity and immobility of the landscape.

For the next two weeks Gordon, Neil and Cyril worked like demented men. They continued on long after nightfall. The few farmers and occasional travellers on the roads who saw the hurricane lamps moving across the darkened landscape declared that no one had ever worked so hard since the Gold Rush. In the belief that the soil was a providing a good sand content they dug down instead of keeping near the surface until a series of caves started forming. They called these holes exotic names like 'Pigs' and 'Tea Leaves', for the obvious reasons. They barrowed the soil up onto the ground level until their muscles were fit to burst. The number of bricks quickly grew to nearly 5,000, but as they dried they started to crack. I was still working in the bank at the time and I remember the numbed feeling I experienced as I read the studiously worded telegram they sent me. 'Bricks already made, now so badly cracked have ceased work, await your arrival Saturday'. When I did finally arrive on the site with the owner's daughter and husband, the long lines of slowly disintegrating bricks gave me a pain over the heart.

Gordon later called it 'the Boulevard of Broken Dreams'. Cyril Jacka's pick, which had worn down some three inches on one side from his incredible activities, was a silent explanation of the zeal of their misdirected energies. It may just be possible that the regular faded lumps are still visible as little mounds merging back into each other as they finally dissolve into eternity. The sand content they thought the soil contained was rotten felspar. It had no binding power at all. A compromise was finally arranged between the owners, the boys and myself, and everyone again set to work, stimulated rather than depressed by the original opposition which had been experienced.

A certain Archer Hancock appeared on the scene. He had lived at Murphy's Creek all his life, had been to Melbourne only once and to the provincial capital of Bendigo four times in the last 30 years. But despite the narrow confines of his daily life, he stood out as head man of that community. He showed how bricks could be made by running the disc ploughs through the topsoil, pushing it into heaps, wetting it down and placing it straight into the moulds. It was a granitic/topsoil, very different from the clays loam of Eltham. It was much easier to mould, yet it was nearly as stable. When the moulds were slipped off, it slumped a little, which caused the bricks, when whitewashed, to look like old stone walls. Gordon Ford and Tony Jackson returned on the second occasion to make the bricks. When the rain would set in on a winter's afternoon they would lie in the shearer's shed listening to the desperate sounds it made on the roof and shake malevolent fists at the sky.

Reg Heather, the farmer who in the depression had walked off a property in the Mallee with nothing but the clothes he stood up in, was an unshakeable realist who was completely philosophical about the inevitability of nature. In his uncomplaining, high-pitched voice, he said: 'Well of course we want the rain, but it's just too bad for the boys'. The boys couldn't see it that way in those early times. They were not used to contending with nature as well as having to get work done simultaneously.

The full story of the Murphy's Creek Homestead is written in my previous book, 'Living in the Environment', so it is not proposed to go over it here, except as it relates to the personalities of those Eltham people who where responsible for its development. They were, almost without exception, witty, original and scintillating personalities that worked on one another so that the place was always in a consistent ripple of laughter, interspersed with loud outbursts of uncontrollable guffaws. What the uninitated thought of the esoteric specialized jokes is not clear, but it is certain that we were well known for miles around. On one occasion we went for a drive for about 12 miles to visit some people who were known to the owners of the farm to be greeted by the words: 'Oh, so you are the strangers in our midst'.

The work went along in five or six week bursts as succeeding wool cheques arrived that had to be disbursed in terms of improvements to keep them out of the rapacious hands of the taxman. Reg and Mrs. Heather, the share farmers, stood at the other end of the social scale from the Eltham people, yet they had much in common because they were all without pretence. They had no suburban jingoism in them. The day the Heathers returned from their first holiday in about 20 years was the day the house was ready for them to live in. A fire was lit in the kitchen fireplace and the firestove was also alight. The effulgence from the firelight that glowed in the room would not equal the rubicund glow which emerged from Reg's face as he rested with his backside against the apron of the chimney. 'I thought it was a fool of a thing when I first saw it', he said. 'But I've never seen a fireplace

work like it'. Indeed, everything about the house had a satisfying reality that was to draw us all into a loving family relationship with each other. The day we packed up and finally left for Melbourne again for the last time, everyone was crying. The stories concerning the Murphy's Creek Homestead and the surrounding towns of Tarnagulla, Moliagul and Dunolly are legion. A few refer to Eltham and its people and must be retold.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >