We Are What We Stand On, Early building experiences

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

Early building experiences

Author: Alistair Knox

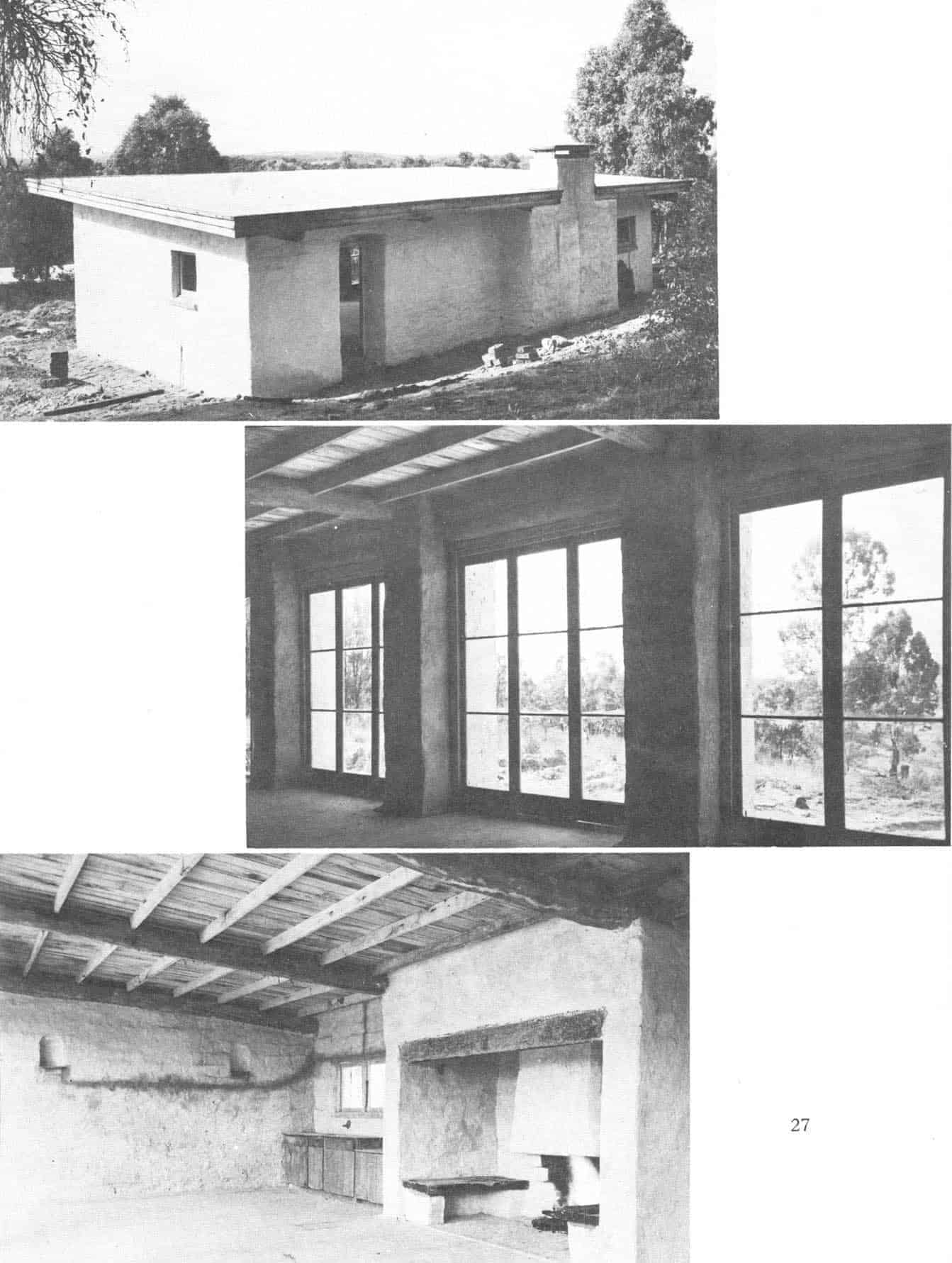

The first earth building I designed in Eltham was for a client named Frank English. He was a returned soldier who had seen earth structures in the Middle East where he served with the Ninth Division at Al Alamien, where Rommel was defeated and finally driven right out of Africa. Frank English had been a good soldier but in peace time he was a gentle person and a male nurse at the Repatriation Hospital. The plan of the house was simple. Its floor plan was only about seven hundred square feet with a large living area and one bedroom, but it was environmental and a new type of building for Melbourne in 1947. It had a skillion roof with five yellow box tree trunks for main beams. These were set on 3' x 2' mud brick piers. Secondary beams of 6" x 2" hardwood had 6" x 1" rough sawn hardwood nailed to them for ceilings. The roof covering was bitumen and creek gravel.

Three views of the English house: Seen from the road. Centre: Interior showing3' x 2' mud brick piers supporting Yellow Box main beams.

Bottom: Showing fireplace and kitchen.

Three views of the English house: Seen from the road. Centre: Interior showing3' x 2' mud brick piers supporting Yellow Box main beams.

Bottom: Showing fireplace and kitchen.

Robin Boyd, the architect and writer, wrote it up in his Age column as a new vision for the new age. Home Beautiful, and other housing publications featured it. I wrote articles in the Age and the Saturday night Herald explaining it. I received letters from many parts of the world concerning both it and earth building generally. The stir it caused attracted a new group of people to move to Eltham. Some were genuinely interested in its possibilities like Eddie Howard, who now lives in the earth building he constructed in Batman Road. I received a phone call from him when we were building the English house and I was still working in a Bank. He was excited and enthusiastic as only Eddie can be, and finished by saying, 'When I saw those mud bricks I jumped for joy'.

Eddie and his son Karl are still jumping in one way or another to the tune of mud bricks. It attracted Gordon Ford, who wasn't very inspired working for the stem-faced and rather unrelenting John Harcourt. There was the artist, John Yule an interesting painter who had up to that time received a kind of subsistence living by sharing his time with his friends. He also wrote obscure poetry and looked rather like a young Professor Piccard, the great underwater man of the period. He was especially attractive to fascinating women. He brought out the mothering instinct in them and later 'got off' with a most elegant French girl, Yvette.

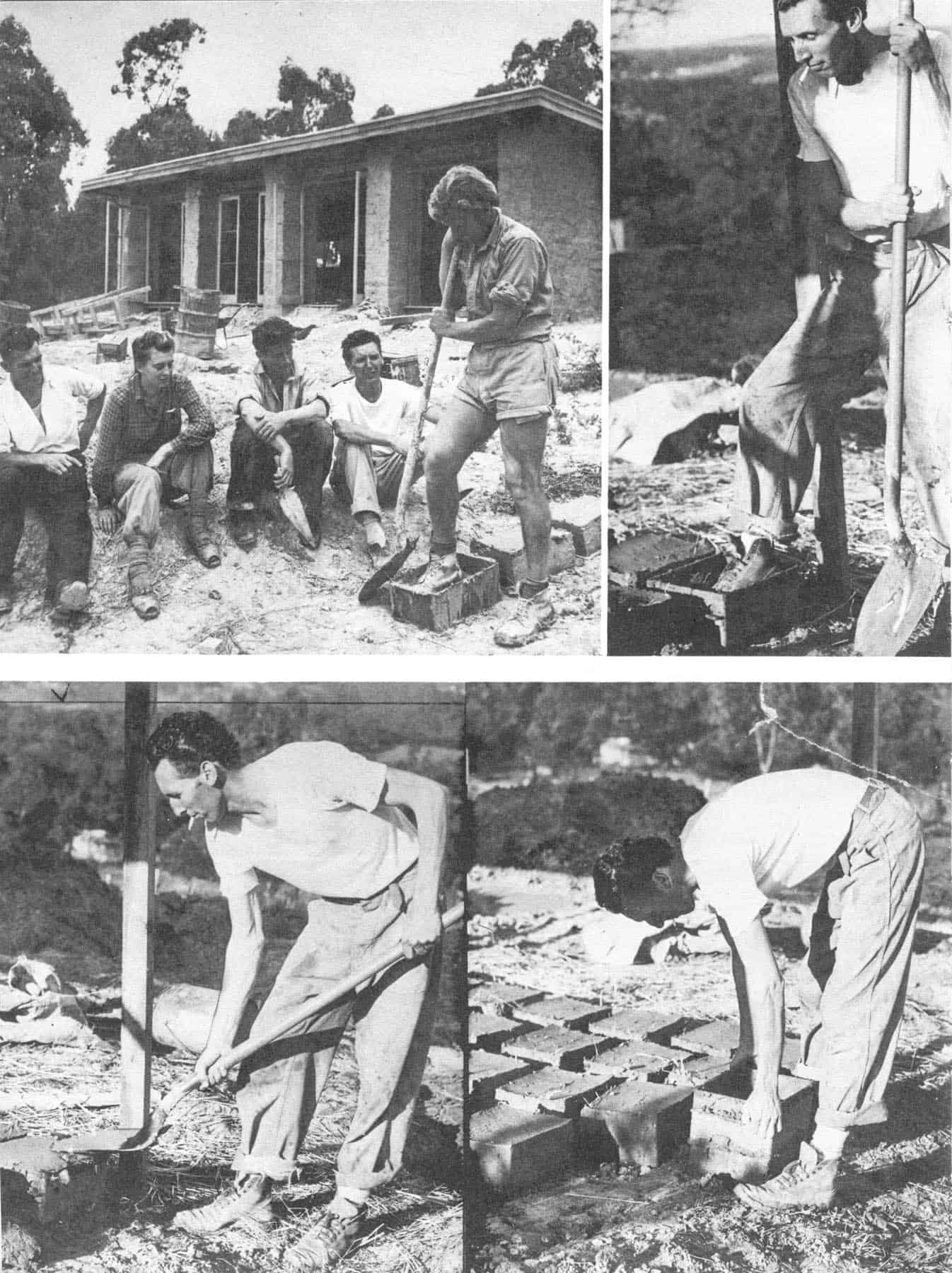

Working on the Frank English house: Top left:

Top right: L to R L. Mayfield, Sonia Skipper, Alistair Knox, Tony Jackson, Gordon Ford.

Bottom: Tony Jackson making mud bricks

Working on the Frank English house: Top left:

Top right: L to R L. Mayfield, Sonia Skipper, Alistair Knox, Tony Jackson, Gordon Ford.

Bottom: Tony Jackson making mud bricks

There was Larry Stevens, who looked like a light-weight Humphrey Bogart and who kept asking, 'Why do they call me Humph?' Larry was a very relaxed personality and thought that work should be treated with a fair degree of deference. Like marriage, it was not to be entered into lightly. They were arranged under the leadership and direction of Sonia Skipper, Matcham's sister, who had ability as a stonemason, laid mud bricks with style and character and was the finisher and decorator of mud brick buildings without equal.

There was no doubt that some workers saw this building as a means of just earning enough to keep them in beer and cigarettes and give them a nice open-air life. Larry pitched a tent in the nearby bush and it was generally felt that he was not given to early rising, although he tried to indicate that he worked nearly full-time each day if there was no way to check up on him. Gordon used to pedal up the mile hill on a bicycle. Sonia would often be seen bounding up the slope on her horse Sherry, to see how it was all going along. Larry would shoot out of his tent at the first faint sound of a horse's hoof, no matter what sort of a hangover he had been enduring within it a moment earlier.

These were the days when very few took working in the open too seriously. The Depression had gone, the war was over. For the first time, one could stand and stare a bit and muse over the wonderful visions of the future. Besides all this the rates of pay were about £1 per day. It was hard to be dissolute on that sort of money, even in those carefree times.

Eventually the building reached a point of practical completion. It was habitable and it had cost between £700 and £800. Frank English's deferred army pay was only about £600. When I asked him for the balance, he said, 'It's no good, Alistair, the boys didn't work, I won't pay'. He stuck to his guns and I realised he had some sort of a case. This work, as with all work, was then undertaken on a cost plus basis because of unpredictably rising costs. This made no difference to Frank. No matter how gentle he was in private life, something of his battling war experience came out in this instance and I finished up paying the difference myself. It was my first lesson of the plans of mice and men going awry. It was not to be the only one. Many years later the building became the property of a Miss Hardress and a Miss Groves, the Eclarte weavers, and fairly extensive alterations were made to it.

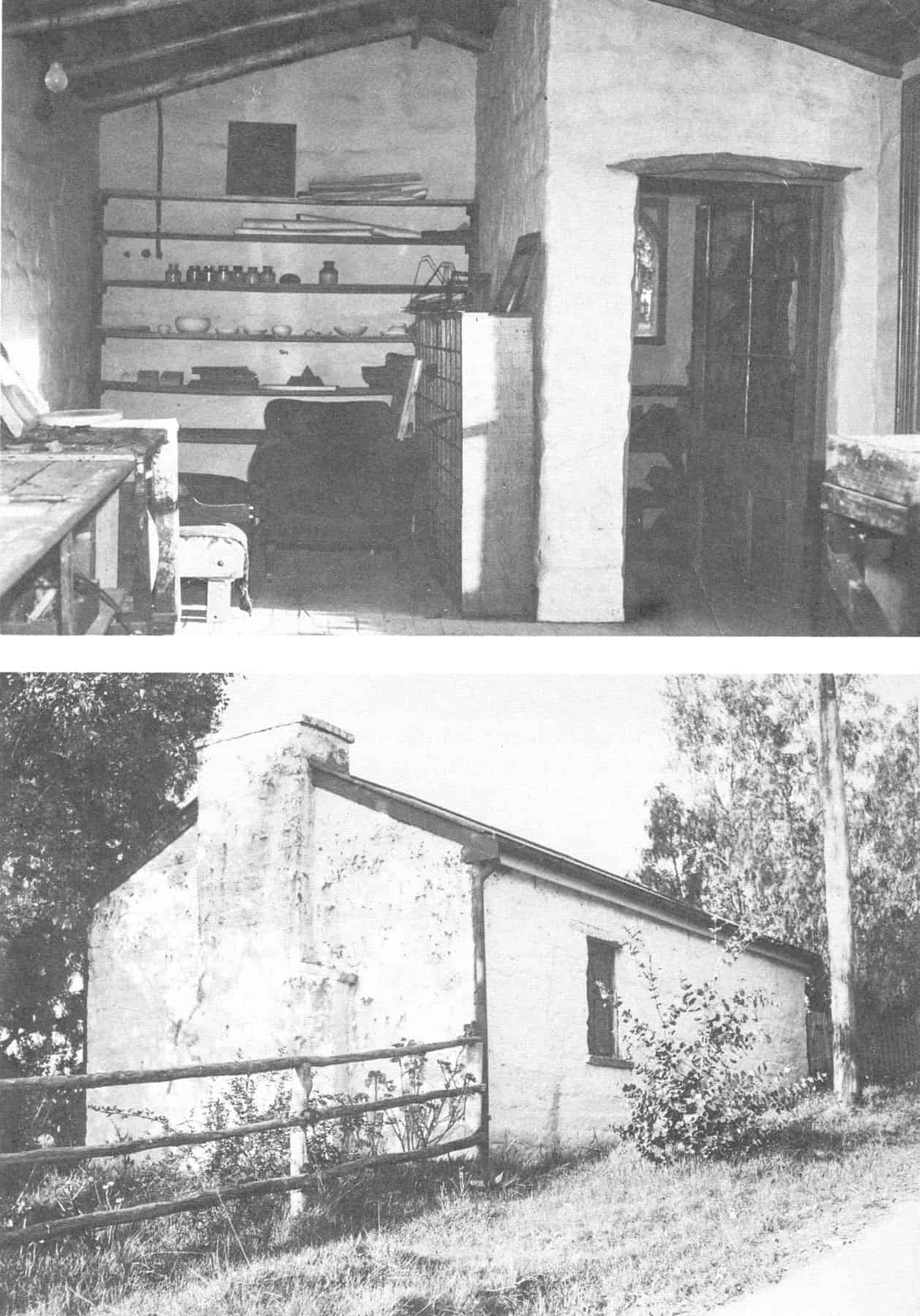

Above top: Katrine Macmahon Ball's studio

Above bottom: Macmahon Ball's studio

Above top: Katrine Macmahon Ball's studio

Above bottom: Macmahon Ball's studio

The second construction I undertook was a study for Professor Macmahon Ball. William Macmahon Ball has been a political scientist of considerable international repute for many years. We built his studio around the time he was Australia's delegate in the Japanese peace negotiations. Our small community drew a quiet sense of reflected glory from him as if we felt we were involved in the negotiations ourselves. It was a pleasant simple construction and both 'Mac' and Katrine encouraged earth building. Peter Glass at about this time built a beautiful earth building for Katrine called 'The Pottery'. He tells an interesting story about it. One of the main walls was not as straight as it could have been and he kept trying to doctor it up, but nothing he did made it agreeable to his accurate artistic eye. One day in a combined fit of despair, rage and conscience he lost his usual gentlemanly calm and rushed in and pushed it all over and started again.

Tony Jackson, a dynamic eccentric, worked with Gordon Ford on the Macmahon Ball Studio. Many hilarious activities took place during the course of its construction. The bricks were made by digging a pit about a foot deep and partly filling it with water. The dam walls were continually widened as the edges were broken back into the water and pugged as it was walked on by the digger moving forward. It was a hard primitive system because the mixing was all done manually and the mixture had to be lifted up to get it out of the hole. Brickmaking has always been a contract deal, which tends to produce a frenetic tinge into otherwise logical people. They are always beset by the decision as to when a brick is a brick and not just a heap of mud. In addition, they are also pursued by the possibility of rain destroying them when in a half-dry condition. If it wasn't too much rain, it could be too little water.

The shortage of water was another hazard. Eltham had a most inadequate water supply, that always failed on the high sides of the central amphitheatre on the hot summer days. The taps were left on full overnight to try and fill the brick-making dams, but the flow was so slow that there would often be only a few inches in the bottom in the morning. Work would begin early before the heat became-too intense and at any time from about 9 a.m. onwards, voices could be heard from the highest point of the hill calling out, 'The water's off'. Once this happened it nearly always stayed off until after dark, unless a cool change came during the day and the taps that always flowed in the valley were turned off.

The moulding of bricks did, however, attract men who had no other skills in building. One such person was Jack McCarthy, a scholarly looking man who lived in Collingwood and ran a library in an old corner shop. It was an unlikely place to earn a prosperous living at this occupation, but Jack liked the Collingwood children who came in to borrow comics and Billy Bunter-type papers. I wondered if he ever made the rent. He volunteered for work when he heard that mud bricks were being made. Each morning he would cut through the paddocks to the site dressed in an old army great coat and boots. He wore glasses that added a distinguished studious quality to his appearance. It was Spring time and the magpies were nesting. They become protective at such periods and swept down like dive bombers on those who dared to pass through their territory. As Gordon and Tony watched Jack approaching one morning, they saw him about to come under fire from a magpie nest and they yelled out to warn him. He just waved back and said they would never actually peck. A moment later they struck and blood quickly flowed from his head. He suddenly started performing a strange dance, holding his cranium and crouching low as he zigzagged out of range.

On another occasion the three were working together. They had a Big Ben alarm clock beside them which rang specific times to gauge their production rate. As lunch time approached, Jack started looking for the clock which had unaccountably disappeared. He plodded around with his army boots inches thick from the mudhole he had been stepping in and out of. It was not until Gordon could recover from his uncontrolled laughter that he was able to point out that the clock was sticking to his boot and that he could not feel its extra weight because of the mud adhering to it.

Although the Macmahon Ball paddock was quite close to the station, the Eltham landscape was wonderfully silent except for the continual singing of the birds and the occasional train going or coming from the city. There were practically no cars travelling the unmade clay and gravel roads surrounding the land. On quiet afternoons, it was possible to look right across to the other side of the valley down as far as the High School a mile southwards. Sometimes you could even distinguish what Mrs. Fabro was calling out to 'Daddy' Fabro and Maurie from the verandah of their traditional Italian farmhouse, which still stands unchanged on the western side ofthe valley. It looks out majestically over rows of cauliflowers, cabbage, globe artichokes and garlic. Nothing could be more European, especially as their acreage was complemented by the Bolla's farm on the other side of Falkiner Street, that ran along the flat land closer to the creek. The Eltham Community had accepted a continental input into its population a couple of decades before the multi-cultural society became a general fact of life and a difficulty to many places in post-war Melbourne. The experience of seeing the elegant longhaired Bolla girls walking smartly down to the bus to go to work each day was a pleasant ingredient in our way of life. Eltham had a wonderful embracing capacity. We were all one people-rich and poor alike. We all knew each other. There was a clear appreciation of everyone's place in our geographically isolated community.

Periwinkle, was, I believe, the most mature mud brick house designed at that period. It related with true understanding to its steep site and expressed the flexibility of earth building with sincerity and authority. It was a positive alternative to architectural thinking that was based on the T -square, the pitched roof and the stud wall. It exploited the flexible nature of earth to develop a new sense of flowing form and shape. The owner, Miss Phyl Busst, had been a student of the Montsalvat Artist's Colony. She and her brother, John, had lived there for some time. John went off to Dunk Island on the North Queensland coast and stayed there for the remainder of his life.

When Phyl Busst decided to return to Eltham, she asked me to design her building for her. It consisted of two large main rooms, a living room and a kitchen area downstairs and a studio and bedroom upstairs. The entry to the house was made at an intermediate level; the bathroom and laundry were placed one above the other in a curved section of the house related to the entry. As it was a steep site, it was decided to bifurcate or split the house along the middle. This made it possible to walk out of the studio bedroom onto the bitumen and creek gravel roofing that covered the timbered ceilings and heavy beams of the living area.

It always struck me as quaint that Phyl, who was at that time reputed to be much more economically secure than most people in Eltham, would have elected to purchase land on that rich-sounding corner of Diamond and Silver Street. Her holding consisted of five standard-sized bush blocks that retain the character of the original landscape of that corner of Eltham to this day. The two-level site was quite complicated because most earth moving was then in its infancy. It was the first time we were able to hire a crawler tractor to do the work and even this highly technological instrument finally had to stand back and await blasting operations in certain parts.

The drilling for explosives was done by hand, Les Punch came into his own on such occasions. He would start drilling into stone to a depth of three or four feet by simply bouncing a type of crowbar called a jumper bar, which he twisted a half-turn every time he hit into the stone. From time to time he would stop and insert a thin rod onto which a small spoon was attached at one end into the hole to ladle out the powdered stone his drilling had produced. It was a slow and painful process which could produce a callous on each hand for every foot of depth that was won. Finally, the dynamite charges would be laid and fired with varying results. Not infrequently, Les had to spit on his hands, laugh philosophically, and start again.

The explosions would echo around the quiet hillside and in a few minutes time odd-looking characters would emerge from the bush. They would look knowingly at the results, pass a few words about the next shot with Les as they sniffed up the lingering fumes of the blast, and dreamt about the day when they worked on the gold mines further up towards the mountains. Horrie Judd was now firmly established as foreman, and he and Gordon Ford, who prided himself on his sun-tanned body and fine physique, would toil side by side to get the site ready for pouring the new-fangled concrete slab.

Others gathered for making bricks. On the first occasion we discussed brickmaking, it was quite late on a cool evening. Neil Douglas, who was one of the volunteers, surveyed the stony-looking soil for a while and then announced he was going up the hill to where he knew there were some mushrooms growing. Neil was the true nature man of the group and the others watched him set off with athletic strides with a quiet, admiring attitude. They felt instinctively, rather than expressed, that if things really got bad he would be able to help them survive in the natural landscape. Neil disappeared over the hill and was forgotten as they discussed the contract price of the bricks to be made. It eventuated that he never returned. He indeed had a very good idea of survival. It had become clear to him that making mud bricks in that place could prove to be beyond the realms of sanity. His survival capacity consisted of knowing when to leave.

Earth building had always contained a strong physical labour content, particularly prior to 1950 before mechanical equipment of all kinds become a daily practice. The pinnacle was reached at the Busst House the day Horrie Judd and Gordon Ford poured the concrete slab. They mixed 52 bags of cement, with the appropriate screenings and coarse sand, into concrete, placed it in position and screened it to a reasonable finish in the one day. They scorned using a mechanical concrete mixer and concrete trucks were not yet available. The method was effective, but when it is remembered that this weight of material to be mixed and placed would be more than 20 tons, i.t gives some gauge of their physical strength and endurance. They first placed the materials in a dry state at the top of the slope and stood opposite each other with the heap between them. They drove their shovels into it and turned it over twice in a dry condition. As it rolled down the hill, the process was repeated after it had been wet down. By the time it reached the edge it was ready for placing. Underlying this vast physical effort were the inflexible wills of two strong men who would have died rather than admitted to each other that they could not have continued.

The Busst house brought out the full flowering of Horrie's physical powers and skills. The strong, flowing shape and monolithic curved walls of the house were magnificently done. He fully grasped the design possibilities. At a time when standard building materials were at their lowest ebb, he contrived to use what was available with character and direction. The problem of fascias, which curved sideways and downwards at the one time, was solved by lapping the double widths of six-inch by one-inch hardwood together in short lengths and butting them to each other, then trimming the curving lines with his tomahawk.

The curving sweeps of the upper ceilings were achieved by combining rafters that ran from side to side of the building and laying two-inch thick 'Solomit' on top of it. This flexible material was again weatherproofed with bitumen and creek gravel. Further rigidity was given to this packed straw ceiling decking by stapling eight-gauge fencing wire at right angles to the rafters. The building has been standing for 30 years and is as sound today as it was when it was erected.

The Downing- Le Gallienne House, stage 1, was commenced shortly after the Busst House was roofed, but still remained unfinished inside. The new house excavation was deep rather than extensive in size, and, because we were not able to get a suitable excavator to it, it was dug by hand. Horrie undertook this work and to some extent was helped by Les Punch and one or two others. The material itself was the most beautiful that could be conceived of for making mud bricks. It was a type of pliable clay, which, when wet, worked like stiff caramel. The excavation angle was about 45 degrees; it had been cut in steps of about one foot by one foot. These bore silent witness year after year to the remarkable stability of the natural ground in that part of Eltham. The building was erected in four stages between 1949 and 1964 and when the last stage was underway, the original steps, which were only earth, were still almost as square as when they were originally dug.

Horrie had acquired a full-time helper called 'Mac' MacDonald. He continued with the Busst House on the west side of the valley while Horrie was working at Downing's, which is in Yarra Braes Road, near Reynolds Road, some 212 miles away. One day, Mac drove over in his Morris Minor to get Horrie back to Busst's for some reason. Horrie left post haste on his trusty bicycle. Yarra Braes Road was very precipitous and more like a river bed than a roadway in 1949. It can still get bad in 1978, but nothing compared to what it then was. Horrie preceded Mac down the steep incline; near the bottom of it he was making about 30 miles an hour when his front wheel caught in a rut. 'Mac' described how he watched Horrie become airborne in one direction with his cycle flying off in the other. It was enough to kill an ordinary man, but all it did to Horrie was to break his thumb. He himself was as undaunted as ever, but was unable to work for some months. This was a serious blow to the ongoing program, but it all held together through others joining in.

Wynn Roberts, who had been a foreman on the second house we built in Heidelberg, was one of these. He was fast developing into a brilliant actor and we were soon to lose his services, but he never lost his love for timber. In his home on the western slopes of the Dandenongs he works part-time making beautiful hand-wrought furniture.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >