Australian Regional Building, Chapter 9: Standard M.S. Method

Chapter 9: Standard M.S. Method

Author: Alistair Knox

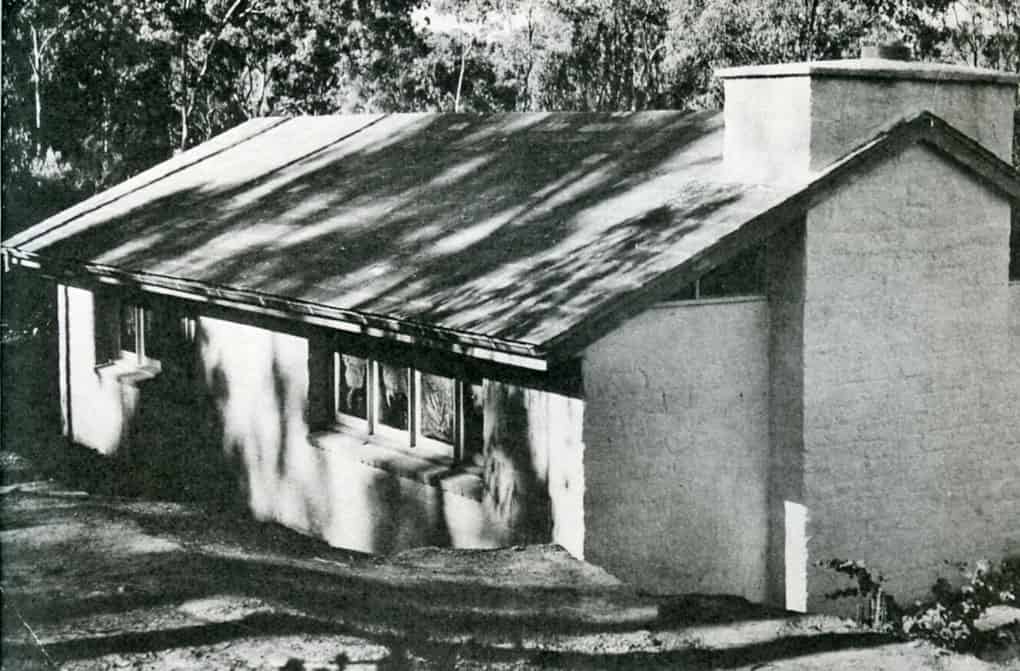

The first stage of the Le Gallienne Downing house 1948

The first stage of the Le Gallienne Downing house 1948

The best early houses I designed and built in earth were the Busst house and the first wing of the LeGallienne Downing house. These were undertaken in 1948 partly because of the fact that material shortages were at their postwar peak, and partly because these clients were people of discretion who really appreciated the medium.

These were the days when Australians of talent were disassociating themselves from the regulations of wartime, and when they had not yet become recognised in the fields of their endeavour.

In its time, my building team has included such illustrious names as Arthur Boyd, David Boyd, Clifton Pugh, Matcham Skipper - now artists of world-wide repute. Earth building was a major movement in those days.

It was also a good way for a regional designer to gain control, not only of a special and remarkable group of men. It is doubtful that anyone quite knew who was actually running the business. The resulting buildings indicate, however, that the designer was able to dominate sufficiently to keep the original character he planned, and still allow the workers to express the inherent qualities of their hands and eyes. It was truly regional building, caught between material shortages and the necessities of staying alive in those in-between years. The realisation that the old order had vanished forever had not fully dawned; the luxurious relaxation of being free from twenty years' threat of disaster was still present in everyone's minds. Once again, there was that ever-recurring picture of the Australian scene. In the early days, it was horror and hope. In the pioneering era, it was brazenness and tenderness. In the late 1940s, it was between lack of materials and an emerging Australian 'image'.

The Busst house was interesting for a number of reasons. The site was steep. Earth moving in Australia was still in the pick-and-shovel thinking stage. The artistic fraternity was not in the least attracted by such instruments as a means of earning a living. Sonia, who had the welfare of the mud brick very much at heart, discovered the wonder man of the adobe block, Horrie Judd. In 1970, Horrie is still producing an undiminished stream of mud bricks and erecting earth houses in various parts of Eltham. He is the strongest and most devoted servant; he has become a legend in his own time. I can remember a doctor of philosophy - a scientist - and equally intelligent man who truthfully believed Judd could move more earth in a given time than a bulldozer.

It was really Horrie who kept the industry going. The earth for the Busst house was dug out by Horrie and Gordon. This earth was set aside for making bricks. Observing what a wonderful level this presented in the first house I built, I calculated the cost of pouring a slab over the whole building site, in the form of a raft. I could see no reason for building up and then laying down a timber floor. The product of the calculations was satisfactory; and the slab floor was built. It has been there ever since. It is part of me. I thought I had invented it. I did not realise that Wright had been using it for years. As far as I was concerned, it was mine. The methods were simple in the extreme. There was not even a waterproofing membrane in those days. There were no special precautions except to observe that there was adequate drainage behind the back edge of the slab. This golden rule of keeping water away instead of dealing with it when it comes remains unchanged. It has stood the test of nearly twenty years, and formed the basis of all slab-construction method, in the state of Victoria at least. When the CSIRO were doing research about slab work, a visit to sites which I had laid down years before caused them to tear up their proposed systems and start again - with mine.

Horrie and Gordon poured the first slab at Busst's. They mixed the whole of it by hand. It was quite a mix; they used fifty-four bags of cement in one day. When it is remembered that this represents some eleven cubic yards of concrete, it will be seen that the ability to work physically had not been entirely lost.

The Busst house in 2015. Photo: Tony Knox

The Busst house in 2015. Photo: Tony Knox

The house itself was composed of two large living rooms - one private, one general. Each had access to the natural ground level, because of the excavated site. The floor of the private wing led onto the roof of the public wing. The entrance was at a landing level. The house was fabricated and welded to the site in a search for inevitable and timeless shapes. A series of piercings in the bricks gave clerestory light to the private wing, which was a bedroom and also a studio. They emphasised the thickness and the flow of the walls. They repeated near the entry and downstairs in a swing-wall section to reflect the dappled quality of light that the bush outside had been offering from time immemorial. It is interesting to look back and realise that I had instinctively reached for the same method as Griffin and Greenway to express the intrinsic essence of the Australian scene with the use of brickwork pattern. This, there was no doubt in my mind, was from the days when I lived opposite the little Griffin house in Heidelberg.

It was also the second occasion on which I used the pier construction, which has always been integral in my mind. The adobe piers in Busst's were 3' x 2', and solid right through. They were set at modular intervals of about 12 feet. Folding glass doors formed a screen between these piers, which give liberal access to the outside. There is an instinctive feeling about this method of a cave. From outside the building, the power of the heavy repeating shapes recalls the primaeval, devoid of time and change. All true design must include timelessness. And the piers have it.

Looking back fifteen years to those early days convinces me I was on the right track. The quest to express the region has always been my prime aim. Yearning for the Eltham pinky-yellow clay may be seen in any of Walter Withers's landscapes of the district; it conjured up a hunger for the immortal. It sends the mind back to the earliest recollections of childhood, to the times when elements were the arbiters of existence and the essence of life.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >