Australian Regional Building, Chapter 1: The Background

Chapter 1: The Background

Author: Alistair Knox

The insularity of Australia during the nineteenth century produced indigenous style in writing, painting, and architecture. Twentieth-century mobility has given an international inflection to these arts. Whatever this has done for writing and painting, it has proved fatal to the spirit of architecture. From the glories of the Parthenon to the charm of the Cotswold cottage, the factor of 'indigenousness' has been a vital and final ingredient.

Technological advances, coupled with the enormous increase in world population, have outstripped the crux of proof by time to direct the development of architectural character in building.

Structures are frequently demolished before they can finally confirm their real architectural quality.

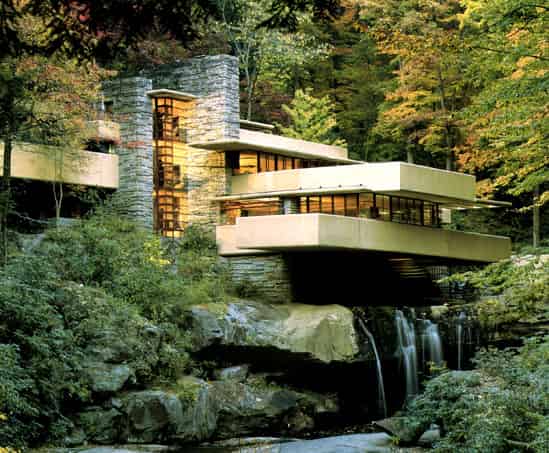

It was against this background that the giants of the first half of the twentieth century wrestled with each other. Frank Lloyd Wright on the one hand - organic; Le Corbusier. Gropius and Mies Van Der Rohe on the other, building in spite of nature. Wright was forming ground-consuming vision of modular dynamics into mediaeval absolutes; Le Corbusier and the others exploiting the time/space elements of the cubists.

Frank Lloyd Wright's Falling Water

Frank Lloyd Wright's Falling Water

Walter Gropius' Bauhaus Archiv

Walter Gropius' Bauhaus Archiv

Wright, master of the non-vertical line and the rock strata, striding with his seven-league boots over the landscape, strewing brilliant concepts across the world. Le Corbusier and Mies foreshadowing the age of automation with glass- and aluminium-faaded structures as precise as honeycomb, as if planned for human bees. Emotion versus intellectualism; the adventure of the new world against the regimentation of the old.

The second half of the century has rebelled against the giants. The shock tactics of the masters began to lose their edge through the sheer force of their statements. Men became immune to the ultimatum of techniques and the ferocious force of extreme individualism.

Both sides of the vast contest produced great buildings. Both produced genius. Frank Lloyd Wright is unquestionably the greatest of this century and indeed possibly of any. But both finally tended to forget them in the pursuit of power.

The first whispered remarks of thinking and deferential people were quieted by bigger and better deurs de force. Gradually, with the ever-mounting tension of the overcrowded roads and the incessant tyrannies of modern existence, the hunger for a new type of architecture became irresistible. The great architecture of the second half of the twentieth century will be of an emerging, rather than a dramatic, character. The pendulum is swinging from the gargantuan to the personal. There is a reassessment of the value of 'sweet' in material and a revulsion against the sweat of nervous tension.

The Australian countryside presents a ready-made background for this return to the primitive. Its hard, dry, vital tenacity remains unconquered. Like a great red ocean, the desert centre grudgingly permits - rather than presents - life. Around its eastern edges the timeless flora still send up wide branches that shed their bark like snakes shedding their old skins. The listless leaves hang edge onto the sun, conscious of the cost of survival.

Day by day, the sun rises in power. Night by night, the stars stream like sapphires on velvet, shafts of light through the primaeval foliage. A bright white moon moves through the tense and listening silence. It remains the land that Cook discovered. It retains the power to move us emotionally as it did Joseph Banks when, Cortez-like, he stood on the shores of Botany Bay.

The broad, God-conscious brush-strokes of nature still create mystery and immensity, these two deep needs of our withering society. Angophoras still grasp the huge sandstone outcrops with their grey trunk-like roots, extending like prehistoric bonsais. The aboriginal has all but gone, but land of myth and eternity remains.

The original colonisers of this land, coming from the dreadful conditions of the convict hulks and the interminable voyages from their homeland, must have stood bewildered on the sands of Botany Bay and Port Jackson. The shackles and the whips were there, to be sure, but this land was full of the cries of birds, primitive black people, grey trees, and blue water. And over all, the sun and the purity ...

The Georgian tradition in building and landscape remained in their hearts, despite the bitter Enclosure Acts and the stealing away of their land privileges. They began to build as they best knew how. The mixture of horrors and hopes that were their daily portion both killed and cured, like salt on wounds. Old England faded; a new England emerged.

Australian building commenced at about the same time as the Enclosure Acts were becoming law in England. It was a time of conflict and deprivation for the non-privileged population. Their historic rights to common lands were being dissolved forever by a series of Acts of Parliament. It affected all parts of the country. A majority of the population who had, to that time, enjoyed unfettered use of open land to supplement their means of livelihood suddenly found themselves without it. Often there was no compensation at all. At other times the dispossessed received a pound or two in money. This was sufficient to purchase enough drink to assuage the despair for a few days, and that was all.

Something like half the village and country labourers' earnings came from keeping a family cow, some geese, perhaps a pig. When the opportunity to do this was gone, the people began to starve.

It can never be accurately estimated what proportion of the early convicts that came to Australia were the result of these cruel laws. The theft of a loaf of bread or the stealing of a sum of money in excess of one shilling was a sufficient crime to warrant transportation to Australia. Those who appreciated the enormous injustice of their position stole rather than starve. England came close to revolution. In France the peasants stormed the Bastille in 1793, although they had never been separated from the land, as was the case in Britain. A factor in history is that similar events often occur in different places at the same time because of parallel conditions. How many disinherited land-users in England experienced the stirring strains of an English Marseillaise within them that cried out for an equality and fraternity irrespective of birth and privilege?

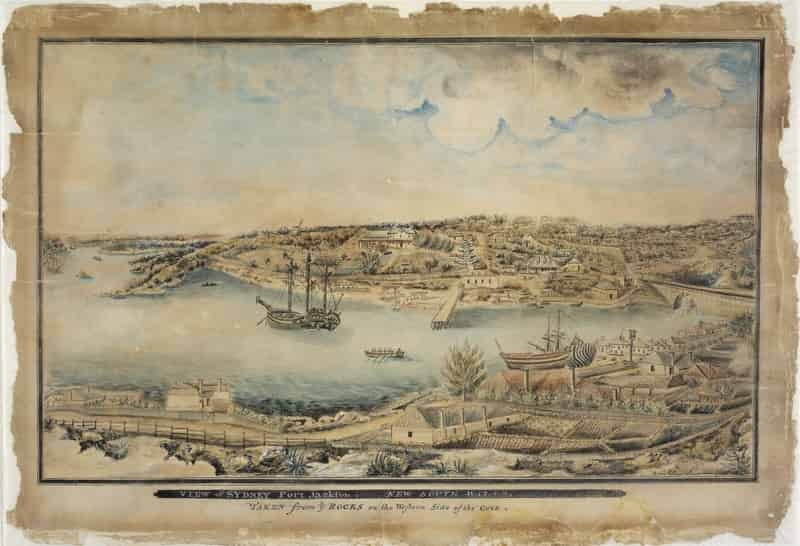

View of Sydney Port Jackson, New South Wales, taken from the Rocks on the western side of the Cove, ca. 1803. Image: State Library of NSW

View of Sydney Port Jackson, New South Wales, taken from the Rocks on the western side of the Cove, ca. 1803. Image: State Library of NSW

When the first fleet furled sail in Botany Bay and the graceful hand-forged anchors were uncatted and lowered, the seamen looked out inquiringly at the sandy yellow beaches and the sweeping landscape. Below deck, the convicts heard the muffled run of the cables from the forepeak of their ships with melancholy foreboding. There was no turning back. The blinding brightness of the sun caused them to see clearly when they came on deck. They were looking out on to a land as full of space for all as the one they had left was without it. The sandstone outcrops, the giant angular foliage, were brilliantly defined by the clearness of the air and the primitiveness of the pattern of the nature.

In the mother country, the privileged minority were enjoying the first fruits of the great informal landscape architecture that is the prerogative of England. Capability Brown had died five years earlier in 1793. Repton was emerging. The scope these men of genius had, with the great new areas of land available through the cheapness of labor, was unparallelled. Poetry and mists - the natural inheritance of England - were transfused into the Renaissance landscape with an impulse that is still apparent. There has never been a richer time of beauty.

Port Jackson was primitive. But its thousand coves, forelands, cliffs, and estuaries were from time immemorial greater than all the softness and fashioning of man.

The leaders of the colony were that mixture of good and bad, strong and weak, that appears in any community. Standing out from the convicts, their conduct and character would have a sense of absolutism. They were the 'gentlemen'. They sprang from a good tradition. Part of that tradition was that those favoured by birth and rank should became men of taste ... and many of them were. This produced a unique opportunity. A fusion of the past and the future, of time, and of tension. On the one hand, the waiting land that had to be habitable. On the other, the recollected order and a pattern. And so it began.

It is still apparent today. One has only to catch Nielson's ferry that passes under the Harbour Bridge to see strong evidence of this quality. As you look back, the view is dominated by the old observatory with its ball tower which gazes back at you with Georgian grace and dignity. The rearward view of the rocks - three and four storeys high, complete with rows of dormers, another fenestration, roofs, and chimney patterns - are at the one time English, yet Australian. The sense of tradition transmuted into yellow sandstone. Moving between the tenders waiting on the discharging freighters, countless glimpses of odd, strange, half-traditional, half-original buildings reflect the early settlement. Old houses run down to the water's edge. The back boundaries consist of great blocks of sandstone built into beautiful walls marked with one hundred and fifty years of rising and falling tides. Here and there, openings in the wall - provided with curious canopies that look oddly familiar to today's carport - surely express that they were once boat-ports. The main means of travel around early Port Jackson was then by water.

The vast, international-type buildings that are rising up and over the pattern of the past look naked, sterile, and sad. They reflect a society that has no power to believe in itself. At best, they are average examples of a style that is so stylised it could find itself in any major city in the world. Bertrand Russell reflects on this when he states how disturbing it is to wake in such a building and not know what country you are in.

On every hand, the old buildings are being destroyed in favour of these mechanical boxes stacked on one another without thought of proportion or suitability to environment. It has become a matter of persons to the acres, of clinical precision. The attitude of some developers of today reflects anger and hate towards the older, more gracious times where the scale was human and man's desire was to express good proportion in structure. They appear unable to comprehend them and so must do away with them forever. Where faith fails, fear begins. There is a fear in the international style of building on any modern city skyline. It is a fear of not conforming to the 'done' thing. A fear of deviating from the narrow line of financial conservatism because it is based on greed and gain. It is business before beauty, money before men. The biggest and dullest buildings belong to banks and insurance companies, oil companies, and hotels. Each is peddling security and comfort to the chief idols of unbelief. Adventure has deteriorated into playing poker machines or gambling on the stock market. Our tough, vital past, despite all its sweat and hard work which can now be done by mechanical means, still bred a far sounder society than the one we have today. Mr Barry Humphries's creation, Mrs Everidge, reflects our social structures as she says there is only one word to describe her daughter Joyleen. She's human - she's a human being! And she smiles contentedly as she tells her neighbour that her fiance's people are very comfortably off.

Glass skyscrapers. Photo: Alistair Knox

Glass skyscrapers. Photo: Alistair Knox

Society cannot live till it believes enough in something to be prepared to die for it. Comfort, conformity, coziness, are not those sorts of things. They are the diseases modern society is dying of. The only certain passion that remains today is a lust for ugliness. In terms of architecture, technique has taken the place of beauty. Technique has become an end in itself rather than a means to an end. The comic tragedy of modern building technique is its grave susceptibility to failure. Melbourne's first skyscraper was enfolded with scaffolding after several uneasy years of its existence.

Large sheets of blue glass that have no other purpose than to hide a concrete facade crash merrily to the ground with monotonous regularity. They have all been replaced, after painting the concrete background blue in the meantime to create an illusion that should never have been there. Function, fiction and stranger than fiction. It is the deceit of a society that has forgotten how to believe in itself. The most abject convict of our early settlement must be turning over in his grave!

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >